Blood Components

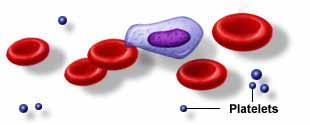

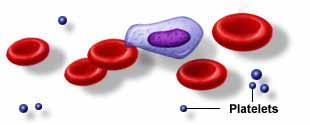

About 55 percent of the blood is composed of a liquid known as plasma. The rest of the blood is made of three major types of cells: red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (leukocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes).

Plasma

Plasma

Plasma is a pale yellowish fluid with a total volume of 2-3 litres in a normal adult. It consists predominantly of water and salts. The kidneys carefully maintain the salt concentration in plasma because small changes in its concentration will cause cells in the body to function improperly. In extreme conditions this can result in coma, or even death. The kidneys also carefully control the pH of plasma within the neutral range of 6.8 to 7.7. Plasma also contains other small molecules, including vitamins, minerals, nutrients, and waste products. The concentrations of all of these molecules must be carefully regulated.

Plasma is usually yellowish in colour due to proteins dissolved in it. However, after a person eats a fatty meal, that person's plasma temporarily develops a milky colour as the blood carries the ingested fats from the intestines to other organs of the body.

Plasma carries a large number of important proteins, including albumin, gamma globulin, and clotting factors.

- Albumin is the main protein in blood. It helps regulate the water content of tissues and blood.

- Gamma globulin is composed of tens of thousands of unique antibody molecules. Antibodies neutralise or help destroy infectious organisms. Each antibody is designed to target one specific invading organism. For example, chicken pox antibody will target chicken pox virus, but will leave an influenza virus unharmed.

- Clotting factors, such as fibrinogen, are involved in forming blood clots that seal leaks after an injury. Plasma that has had the clotting factors removed is called serum. Both serum and plasma are easy to store and have many medical uses.

Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes)

Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes)

Red blood cells are the most common cells found in blood. They make up almost 45 percent of the blood volume There are about 5 million red blood cells in each cubic millimetre of blood; 250 million red blood cells in every drop of blood. This number varies with individuals in accordance to heredity, gender and state of health. These cells are produced by the bone marrow and have a lifespan of 3-4 months. When they die, they are destroyed by macrophages in the liver and spleen. This process releases iron to be stored in the liver and bile pigments to be excreted.

Structure of A Red Blood Cell

Structure of A Red Blood Cell

Red blood cells have a bi-concave shape with a flattened centre. It has a diameter less than 0.01 millimetres and does not have a nucleus. Red blood cells contain a protein chemical known as haemoglobin, which gives it the red colour. Haemoglobin contains iron, which can easily transport gases such as oxygen and carbon dioxide. Red blood cells are highly elastic, rendering it able to squeeze through capillary walls bigger than itself.

Functions of Red Blood Cells

Their primary function is to carry oxygen from the lungs to every cell in the body in the process of respiration. Gases involved in respiration are carried around the body through these cells. Oxygen readily combines with haemoglobin to form oxy-haemoglobin in the lungs where there is high concentration of oxygen. As blood passes through body tissues, hemoglobin then releases the oxygen to cells throughout the body. Red blood cells also carry part of the carbon dioxide waste from the cells through most is transmitted through plasma as soluble carbonates.

The membrane, or outer layer, of the red blood cell is flexible, like a soap bubble, and is able to bend in many directions without breaking. This is important because the red blood cells must be able to pass through the tiniest blood vessels, the capillaries, to deliver oxygen wherever it is needed. The capillaries are so narrow that the red blood cells, normally shaped like a disk with a concave top and bottom, must bend and twist to maneuver single file through them.

White Blood Cells

White Blood Cells

White blood cells only make up about 1 percent of blood, but

their small number belies their immense importance. They play a vital role in the body's immune system, the primary defense mechanism against invading bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. They often accomplish this goal through direct attack, which usually involves identifying the invading organism as foreign, attaching to it, and then destroying it.

White blood cells also produce antibodies, which are released into the circulating blood to target and attach to foreign organisms. After attachment, the antibody may neutralize the organism, or it may elicit help from other immune system cells to destroy the foreign substance.

There are several varieties of white blood cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, all of which interact with one another and with plasma proteins and other cell types to form the complex and highly effective immune system.

Platelets and Clotting

Platelets and Clotting

The platelets are the smallest cells in the blood, which are designed to begin the process of coagulation, or forming a clot, whenever a blood vessel is broken. As soon as an artery or vein is injured, the platelets in the area of the injury begin to clump together and stick to the edges of the cut.

They also release messengers into the blood that perform a variety of functions:

- constricting the blood vessels to reduce bleeding,

- attracting more platelets to the area to enlarge the platelet plug, and initiating the work of plasma-based clotting factors, such as fibrinogen.

Through a complex mechanism involving many steps and many clotting factors, the plasma protein fibrinogen is transformed into long, sticky threads of fibrin. Together, the platelets and the fibrin create an intertwined meshwork that forms a stable clot. This self-sealing aspect of the blood is crucial to survival.

Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes)

Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes)

White Blood Cells

White Blood Cells  their small number belies their immense importance. They play a vital role in the body's immune system, the primary defense mechanism against invading bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. They often accomplish this goal through direct attack, which usually involves identifying the invading organism as foreign, attaching to it, and then destroying it.

their small number belies their immense importance. They play a vital role in the body's immune system, the primary defense mechanism against invading bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. They often accomplish this goal through direct attack, which usually involves identifying the invading organism as foreign, attaching to it, and then destroying it.  White blood cells also produce antibodies, which are released into the circulating blood to target and attach to foreign organisms. After attachment, the antibody may neutralize the organism, or it may elicit help from other immune system cells to destroy the foreign substance.

White blood cells also produce antibodies, which are released into the circulating blood to target and attach to foreign organisms. After attachment, the antibody may neutralize the organism, or it may elicit help from other immune system cells to destroy the foreign substance.  There are several varieties of white blood cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, all of which interact with one another and with plasma proteins and other cell types to form the complex and highly effective immune system.

There are several varieties of white blood cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, all of which interact with one another and with plasma proteins and other cell types to form the complex and highly effective immune system.

The platelets are the smallest cells in the blood, which are designed to begin the process of coagulation, or forming a clot, whenever a blood vessel is broken. As soon as an artery or vein is injured, the platelets in the area of the injury begin to clump together and stick to the edges of the cut.

The platelets are the smallest cells in the blood, which are designed to begin the process of coagulation, or forming a clot, whenever a blood vessel is broken. As soon as an artery or vein is injured, the platelets in the area of the injury begin to clump together and stick to the edges of the cut.