is reclaimed for the big-eared bats who need it most . . .

A GRAND EFFORT IN THE GRAND CANYON By Mike Quinn and Jim Petterson

"What an experience! Gibson is so affected by Henry's death that he is crying like a child, and it is all we can do to keep him from starting right up over the cliffs back to Lee's ferry." As they carried their pots, pans, tools, and oars into the cave's dim reaches, they probably didn't realize they were being watched by several hundred individuals hanging from the ceiling. Stanton's party likely intruded on a summer maternity colony of Townsend's big-eared bats (Corynorhinus townsendii). The cave, now named after the intrepid explorer, once housed the largest maternity colony of this species known in Arizona. Female bats gathered from a wide area to roost and raise their young together. The small bats ate thousands of insects and served as a vital part of the canyon ecosystem.

To set the record straight, a major archaeological excavation was undertaken in the summers of 1969 and '70. The dust and noise from working in the cave on a daily basis almost certainly caused the bats to flee the cave for those two summers, which in turn hindered their reproduction.

After excavation was complete, the cave entrance was covered with a chain-link fence to preserve the historic resources. The fencing also had the unfortunate effect of shutting out the bats that had already fled the cave and shutting in any bats left inside. In the center was a door made of rebar stabilizers, but the spaces in the door and the fencing were not large enough for bats to easily maneuver.

An effort was made in the fall of 1995 to shore up holes in the existing gate. In July of 1996, approximately 20 bats were seen exiting the cave, and roosting in the cave. Closer examination and ultrasonic recordings confirmed the presence of Townsend's big-eared bats. This observation represented the first evidence since the late 1970s that bats were attempting to reoccupy the cave.

Inspired by this good news, Grand Canyon wildlife biologist Jim Petterson proposed replacing the current gate with one that would allow pregnant and juvenile bats easier access while preventing human passage. It quickly became obvious that the project would require the support of many different organizations, but luckily all of them proved more than willing. The National Park Service supplied boats, boatmen, welders, and support staff. Bob Currie of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) designed the gate and supervised its construction. Through the coordination of BCI's new North American Bat Conservation Partnership (NABCP), the Park staff received direct financial assistance from BCI and technical aid from BCI biologist Dan Taylor and Associate Executive Director Steve Walker. Also, in keeping with the spirit and interest of the NABCP, Park Service dollars were matched three to one by the Arizona Game and Fish Department, the USFWS, the U.S. Geological Survey, and BCI. The project was finally ready to go.

A second river trip, in April 1997, hauled two arc-welding units, a generator, several hundred feet of electrical cables, and the acetylene bottles and oxygen tanks (perhaps the most dangerous component; they can easily detonate if mishandled.) Members of the second crew actually constructed the gate.

In other caves where Townsend's big-eared bats have been protected with similar gates, the bats have reoccupied the site after only a few months. Grand Canyon wildlife staff are monitoring Stanton's Cave to document the expected recovery of the cave colony. During a bat survey river trip in May 1997, 120 bats were observed exiting the cave in the early evening dusk. Evidently this secure haven is precisely what they had been waiting for. So wrote Robert Brewster Stanton in July of 1889 after three of his party drowned in Marble Canyon, now part of Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona. The men had been surveying a gorge in the Grand Canyon for possible railroad construction through the Colorado River's scenic canyons. (A dream, fortunately, never realized.) Now they were unable to continue; it was time to retreat.

So wrote Robert Brewster Stanton in July of 1889 after three of his party drowned in Marble Canyon, now part of Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona. The men had been surveying a gorge in the Grand Canyon for possible railroad construction through the Colorado River's scenic canyons. (A dream, fortunately, never realized.) Now they were unable to continue; it was time to retreat.

It was drizzling at mile 31 of the Colorado River as the survivors neared Vasey's Paradise. Climbing the Redwall limestone bench above the river they found, "a whole row of cliff dwellings, with pieces of broken pottery all over the cliff." From there, a prehistoric trail led up South Canyon - their escape! Before they began the climb, however, Stanton decided to cache their remaining supplies. He chose a cave in the limestone rock face about 160 feet above the river.

It was drizzling at mile 31 of the Colorado River as the survivors neared Vasey's Paradise. Climbing the Redwall limestone bench above the river they found, "a whole row of cliff dwellings, with pieces of broken pottery all over the cliff." From there, a prehistoric trail led up South Canyon - their escape! Before they began the climb, however, Stanton decided to cache their remaining supplies. He chose a cave in the limestone rock face about 160 feet above the river.

Townsend's big-eared bats are particularly sensitive to human disturbance, with some colonies vacating a cave after being disturbed as few as two times. If approached too closely, the entire colony may take flight, abandoning their young. Unfortunately, modern visitors to the Grand Canyon have been drawn to Stanton's Cave, not only by its size and mystery, but by stories of the prehistoric artifacts buried within - some thousands of years old. A growing numbers of hikers, splunkers, and river runners have sought out the cave for these reasons, causing repeated disturbances for the bats.

Townsend's big-eared bats are particularly sensitive to human disturbance, with some colonies vacating a cave after being disturbed as few as two times. If approached too closely, the entire colony may take flight, abandoning their young. Unfortunately, modern visitors to the Grand Canyon have been drawn to Stanton's Cave, not only by its size and mystery, but by stories of the prehistoric artifacts buried within - some thousands of years old. A growing numbers of hikers, splunkers, and river runners have sought out the cave for these reasons, causing repeated disturbances for the bats.

The excavation, from any perspective other than the bats', was a huge success. The archaeologists unearthed extraordinary artifacts: more than sixty "split-twig" animal figurines made by a prehistoric culture between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago; a layer of animal and plant remains dating from the Pleistocene, including bones of California condors and extinct mountain goats; and a layer of driftwood and lake sediments deposited in the cave more than 37,000 years ago. The cave was found to be a significant archeological and paleontological site, suitable for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

The excavation, from any perspective other than the bats', was a huge success. The archaeologists unearthed extraordinary artifacts: more than sixty "split-twig" animal figurines made by a prehistoric culture between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago; a layer of animal and plant remains dating from the Pleistocene, including bones of California condors and extinct mountain goats; and a layer of driftwood and lake sediments deposited in the cave more than 37,000 years ago. The cave was found to be a significant archeological and paleontological site, suitable for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Later studies documented a rapid further decline of the Stanton's Cave bat colony following installation of the fencing. By 1986, the cave was empty of its former inhabitants, and there were only five known maternity colonies left in the state. At that time, a recommendation was made to cut a hole at the top of the chain link gate to allow free passage for bats. The modification was made, but no bats were seen using the cave for maternity roosting in the following years. The hole, while allowing bats a passageway, also gave people relatively easy access. In addition, inconsistent efforts at repairing the frequent cuts and breaks in the lower sections of the gate meant that almost anyone could gain entrance to Stanton's Cave.

Later studies documented a rapid further decline of the Stanton's Cave bat colony following installation of the fencing. By 1986, the cave was empty of its former inhabitants, and there were only five known maternity colonies left in the state. At that time, a recommendation was made to cut a hole at the top of the chain link gate to allow free passage for bats. The modification was made, but no bats were seen using the cave for maternity roosting in the following years. The hole, while allowing bats a passageway, also gave people relatively easy access. In addition, inconsistent efforts at repairing the frequent cuts and breaks in the lower sections of the gate meant that almost anyone could gain entrance to Stanton's Cave.

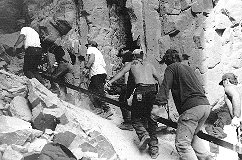

The process of getting all the materials to the cave was a bold adventure almost in the league of Stanton's original trip. In February 1997, two 37-foot rafts made the 31 mile trip down the river, hauling 8,000 pounds of steel as well as other supplies. The purpose of this trip was to bring in the structural materials. Members of the Grand Canyon Trail Crew carried each 200-pound steel bar - by hand - up the rocky, 160-foot vertical rise from the river to the cave.

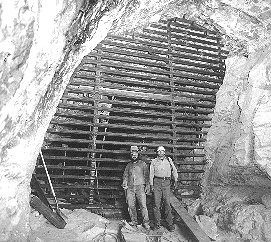

The process of getting all the materials to the cave was a bold adventure almost in the league of Stanton's original trip. In February 1997, two 37-foot rafts made the 31 mile trip down the river, hauling 8,000 pounds of steel as well as other supplies. The purpose of this trip was to bring in the structural materials. Members of the Grand Canyon Trail Crew carried each 200-pound steel bar - by hand - up the rocky, 160-foot vertical rise from the river to the cave. The 20-foot steel pieces were measured and cut to precise length then welded into place. The result is an immense gate, about 20 feet tall by 20 feet wide, set back from the mouth and just barely visible from the river. With horizontal spaces 5 3/4 inches wide and 6 to 12 feet long, there is sufficient area for bats to pass through, but none large enough for humans.

The 20-foot steel pieces were measured and cut to precise length then welded into place. The result is an immense gate, about 20 feet tall by 20 feet wide, set back from the mouth and just barely visible from the river. With horizontal spaces 5 3/4 inches wide and 6 to 12 feet long, there is sufficient area for bats to pass through, but none large enough for humans.

Mike Quinn documented the 1997 gating expedition as Museum Photographer for Grand Canyon National Park. Jim Petterson was formerly the Wildlife Biologist at Grand Canyon National Park and is now an Ecologist at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

Viewing the gate at Stanton's Cave is difficult because of its remote location. A strenuous, full-day hike (with at an overnight camping permit) is required, or an expensive week-long raft trip.

Versions of this article appeared in the Fall 1997 Edition of Grand Canyon National Park's NATURE NOTES; edited by Greer Cheshire, and the Fall 1997 Edition of Bat Conservation International's BATS; edited by Sara McCabe.

Mike Mahanay - Nankoweap to Phantom Ranch Backpack Trek

Visit BAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL

This page hosted by ![]() Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page