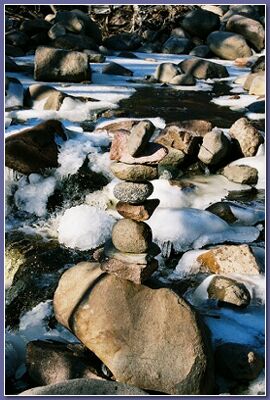

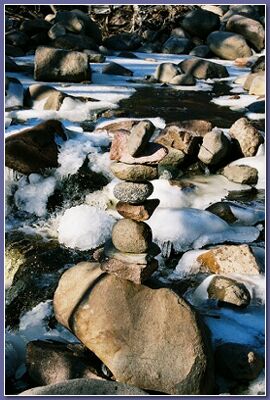

Steep stairs carpeted with water. Two rocks in the stream surrounded by ice like albumen around yolks. White birches and blue sky reflected in a pool.

Steep stairs carpeted with water. Two rocks in the stream surrounded by ice like albumen around yolks. White birches and blue sky reflected in a pool.

"To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work."

--Mary Oliver, Owls and Other Fantasies

Constriction has ruled our lives long enough. Rigid rules, societal strictures, unexamined morality, failures of the imagination: Prevailing institutions encourage such bondage. But it neednít be so.

Friday

Clear sky over Minneapolis. At dawn the air temperature is 18 degrees Fahrenheit, the coldest morning of the season. A skin of ice has appeared under the pedestrian bridge in Loring Park.

Antsy all week to be out of doors, I desert my indoor complaints at noon and head into bright sunshine, then drive my little red wagon onto the interstate, northbound.

Always I want to be going north. Now I am again.

Soaring overhead: A red-tailed hawk.

Just short of a hundred miles north of the urbs, I stop briefly to stretch and pee.

Graffiti above a urinal: "Tupac lives." Itís not true. Tupac caput.

No dawdling now. I zip through my favorite St. Louis County city, eschew the scenic route, and take the shorter expressway to Two Harbors where I stop to procure some provisions for the days ahead. Chocolate, for example. Water.

Things I donít have and wonít need: thermos, shovel, laptop, comic books, cigars, sanitary pads, nitroglycerin.

I pass a sign for Cant Road. For a second I think it says Cant Read.

Lake Superior today is deep blue, and white waves splash from it onto rocks along the shore.

As I move north on four wheels, the sky dims and the sunís bright orb turns speed limit signs from white to fluorescent orange.

Ontario license plates are embossed with the motto, "Yours to Discover." An invitation for licentious behavior.

Now the pale blue sky over the big water is streaked with pink cirrus clouds.

Grand Marais, Minnesota, population 1353, is home to a whole foods co-op, a community radio station, the North House Folk School, and an espresso-slinging coffee shop (Java Moose), among other things. If Iíd timed my travel differently -- and come next week-- I would have been able to attend an international Arctic film festival.

At Buckís Conoco/Hardware Hank I fill my tank. Inside to pay, the customer ahead of me sports a blaze orange cap. The woman cashier wears a button that says "Peace & Justice." Damn right.

I rent a cheap motel room and walk down the road to The Pie Place, a restaurant claiming to serve "gourmet home cooking." The claim is nearfetched. The Place is located in a big old house where I sit on the porch enjoying baked crab cakes, carrots (steamed?), broiled potatoes, and salad--instead of radish dill soup--with pesto dressing.

After dinner, a partial reading of the pie list is enough to satiate: Maple pecan. Pumpkin praline. Caramel almond apple. Banana cream.

Is this place a mother and son business?

I donít sense that many people in this town are tattooed.

Good.

Iím still on city time. The pace seems a hair too slow.

"Too slow" should be an oxymoron.

Back in Room 107 I succumb to the novelty of cable television. I turn it on and thereís a French language instructional program airing. I sit transfixed for the duration of the show, then change the channel.

Whatís this? Before Iím fully conscious of it, Iíve watched a half hour MTV program called "Pimp My Ride" in which young people with old beaters are awarded custom body jobs. (Their cars are made gaudy.)

Afterward I feel like taking another shower, as if Iíd gotten dirty watching television. I have about as much self-control with TV as I have with M&Ms and potato chips, which is why I avoid them.

A colleague of mine says heís concerned about his own "moral anorexia" in not owning a car. Iím still thinking about that.

What would a bulimic drive?

Saturday

The Cascade River flows into Lake Superior about ten miles south of Grand Marais. A state park here extends about five miles each direction along the lakeshore, never going more than a mile inland.

Bright sunshine again. Itís cold out, and ice has formed on stones in the river and along cascades partly colored by blue shadows. Where the sun shines through trees, the ice sparkles.

I hear a raven (Grok!), and look up. There it goes.

Here I am.

Listening to the music of water over rocks. And now to the rumble of a waterfallís tireless engine.

Rivers in this region run yellowish-brown, due to humic acid (from humus). Not from urine.

Beside the trail a doe feeds quietly in a power line cut.

For a minute or two Iím wishful. "I should have camped," I think.

From out of the blue, "O Come Emmanuel" enters my brain and plays there for about fifteen minutes. Then the sound of the freshets, rills, and other tributaries--gurgling trickles-- chases it away.

Red squirrels here are evidently used to human visitors. One perches on a limb not four feet from me.

The woods are wild and green with moss and lichens. Home to chickadee and woodpecker. And visited now by four deer hunters, one dragging a bloody blue plastic sledge. Iím going the opposite way.

Humans have the hubris to think they can manage "natural resources." They should learn to manage themselves.

Bears collared with radio transmitters. Canada geese with numbered bands on their necks. This is wrong. Imagine if people did this to their own species.

They do?

As I stop to rest, an eagle soars overhead in tight circles, sunlight catching its white head and tail.

Then Iím back on the trail with my longtime companion, Shadow.

Tangle of curved roots that look like snakes, icicles hanging from mossy rocks at a riverbend, torn pages of a birch tree, falls shaped like a long white tongue, pool at the base of falls, icy teeth framing golden water: A masterpiece at every step.

At the mouth of the Cascade, Superiorís waves pound onto black rocks, wet explosions that seem positively sexual.

"Our truest life is when we are in dreams awake," Thoreau writes in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

The distance between sun and horizon grows small. Then a rosy glow appears.

Then darkness.

Sunday

Sunny and mild. Iím clambering up the Onion River this morning, making my way along no human-made trail, fording the stream back and forth as necessary when one side becomes sheer cliff.

I explore a deep chasm that leads to a waterfall, then backtrack for a while and climb up over the rim around it. Once again Iím reminded of Utah.

The way is sometimes a rocky and wet way.

Steep stairs carpeted with water. Two rocks in the stream surrounded by ice like albumen around yolks. White birches and blue sky reflected in a pool.

Steep stairs carpeted with water. Two rocks in the stream surrounded by ice like albumen around yolks. White birches and blue sky reflected in a pool.

I watch in the sky as a raven and hawk engage in a dogfight. (Raven aggressor.)

After hiking slowly upstream for about three hours, with some stops to play, Iím inadvertently baptized. Intending to cross the water, my left foot slips on an icy rock and I plunge in up to mid-thigh.

Nothing to do but climb out and make my way to sunny rocks, sit down, pull off shoes and socks, wring out the latter, doff my pants, and don a pair of longjohns Iíve stowed in my knapsack. Belatedly I empty yellow water from my boots.

Onward. Or so I think.

But I think again and decide it might be a good idea to hike back to my car and return to the motel for dry pants and shoes. It happens that my baptism has taken place near a road. I choose to walk along this route instead of retracing my way along the stream.

Referring to the nearby Kadunce River, the Guide to the Superior Hiking Trail advises: "Hikers will get wet up to their thighs." The book gives no such warning for the Onion. (Itís not part of the human-made trail, after all.) "Cold and damp,--are they not as rich experience as warmth and dryness?," Thoreau wondered.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers is an odd duck. The book--about which Thoreau famously wrote that he owned a library of nearly 900 volumes, "over seven hundred of which I wrote myself"--is structured around a fraternal boating/camping expedition, a thin frame to which are attached poems and poetic fragments,both quoted and original, as well as long digressions on friendship, art, history, poetry, and other concerns.

By mid-afternoon, dried out, I hike along the rim above the Devil Track River that enters Superior about four miles north of Grand Marais.

Big Mary.

Birches grow like silver hair above tall cliffs.

Iím limping a bit, but these injuries are minor. Iíve healed after deeper wounds recently. (So I tell myself.)

At dusk I watch waves, apparently taller than distant trees and hills, crash onto the breakwater outside Grand Marais harbor. The leaping spume is colored salmon by the setting sun.

Of course the sun doesnít set. The earth devours it.

People pay big money to see spectacular movies and procure psychedelic drugs, but the best show is right here, right now.

The sky in which my face swims displays an ever-changing mixture of pink, fuchsia, violet, and slate, while the earth spins like a top, sloshing back and forth the waves Iím watching lap toward my feet.

To ride waves one must hold on to nothing.

For dinner I visit the Gun Flint Tavern where a television is turned off-- a happy fact. Instead: mariachi music.

Tonight, Mexican music is as good as no music at all.

Among the "hand-crafted beer" available here: Superior Special Ale, brewed 110 miles away in Duluth. Bueno cerveza.

Shavings,, the newsletter of the North House Folk School, mentions that a historic fish house has been rebuilt that was destroyed last January after a truck with ineffectual brakes plummeted down the steep Gunflint Trail. (It seems the semi-tractor-trailer went right through the building and into the lake.)

Enchiladas queso con mariachi... A good combo.

Thereís a beer called Moose Drool? Ouache!

I just realized that the whole time I watched that light show in the sky, I felt no pain in my left thigh.

Timeless time is the very best kind.

I could have had "potato Roquefort soup" here, so-called. Sounds good. Would it have tasted good?

A silver-haired guy with a pony-tail walks in. "I listened to your music afterwards," I hear the bartender say.

I also overhear: "My name is Jay."

Till now Iíve overlooked the concept of olfactory eavesdropping, things we oversmell. ("Get a whiff of that!")

According to a lifeless clock on the wall, itís perpetually 11:15 Blue Moon time. Eh-em or pee-em, your choice.

An editorial cartoon in the weekly News-Herald lampoons the fact the Grand Marais now has a stoplight.

I go for a stroll along the harbor after dinner, near the tiny Coast Guard outpost, and crane my neck upward.

What does it mean to be disappointed?

There are no stars visible from this scrap of land tonight, but theyíre out there all the same, just as people are out there in the world.

How close shall we be?

You who have ears, hear my prayer.

Monday

Dawn. Iím up before light and out walking--hobbling, actually--along the rocks at "Artistís Point," so-called.

Gulls come singly from the lake. Do they live out there and sleep in the sky?

Two bright planets appear in the east.

Call this "Photographerís Point." Or "Poetís Point."

How about "Namerís Point?"

(One of my favorite forms of self-entertainment is onomastics.)

Writes Thoreau, "I value and trust those who love and praise my aspiration rather than my performance."

A nameless ridge of clouds stretches across the eastern horizon, above which a rosy glow appears.

Thin ice has formed on puddles in the orange-lichen-covered rocks.

I watch as the sea slowly spits its orange seed.

Dawn.

Just after the sun has crested the ridge of clouds, its light shines on the sea like a beacon. Framed now between two rocks, on the surface of the water: A wide, gold shimmering line.

Iíd like to walk that trail.

Who is to say what dreams are possible?

I tear myself away, and go back to the motel for breakfast, two bagels smeared with peanut butter and jam.

Before I head out of town for the day, I visit Chuckís Barbershop, open at 8:30. With not a soul in sight, I sit and glance through daily paper from Duluth till Chuck (I presume) pops his head in the door and says heíll be with me shortly. The newspaper contains no news at all. The news is Iím about to have my first professional haircut in a long time.

Chuck pegs me for a teacher. Heís not far off.

Who isnít a teacher?

Now I hike clean-headed to the Devil Track River again from a different direction than yesterday, a section of the Superior Hiking Trail that runs from the Gunflint Trail two miles north of town, past a rocky bluff called Pincushion Mountain that overlooks Lake Superior on one side and wooded hills on the other.

Where does the sea become the sky?

I eat my almonds and apricots as I watch ravens play hide-and-seek below.

But for Superior this could be Bear Mountain in the Berkshire Taconics.

The solid rock on which I park my rear is striated with straight intersecting lines, in some of which grow moss. Everywhere the rock is covered with lichens, flat blobs of bright yellowish-green and pale whitish-green.

Living matters.

This is a good place. Somewhere down there, amidst and below those birches, the Devil Track flows.

Back in the woods again: One unruffled ruffed grouse struts off wearing white feathery spats. Here a single yellow dandelion blossoms, withered but hanging on to its hue.

I exult that there are dandelions.

The deep Devil Track canyon is dark and cool. Cousin to the Manitou, the river cuts through hillsides lit with bright green moss that everywhere grows on rocks and downed trees.

Here is a bridge across.

To stay or to go? As I ponder, Iím graced with the presence of another eagle.

Now, hiking back through woods, Iím priveleged to encounter a majestic, prehistoric pileated woodpecker.

At close of day, I spend an hour or two along the nearby Kadunce River whose mouth only Iíve previously explored. Through birches there I watch the sun catch briefly upon a dark ridge.

A four-foot disk of ice circles in a backwater.

On a beach covered with small smooth stones, the mouth of the Kadunce disappears into a still pool. The sun, trailing a wisp of cloud as if itís smoking, vanishes beyond a cape to the southwest, leaving a thin sliver of white moon in its wake.

A while later, back in town, I see the moon again, now yellow-gold in a blue-black sky. Then it too goes hiding.

For three days now Iíve encountered no other humans on the trail. A blessing.

Iím happy to commune with Corvus corax,. (It feels wrong not to live where ravens thrive.)

Allanís hummingbird, Clarkís grebe, Lucyís warbler. Thus have some bird species been called by humans. Name me after a bird.

Five miles from Grand Marais harbor, a single black rock juts out in the lake. Of what use is Five Mile Rock?

Of what use am I? Iím forced by circumstance to write these very words. They take the place of things I canít this instant do. They take the place of wings.

Theyíre the next best thing to a technology that would vaporize capitalism and majoritarianism.

With words I strive to imagine the unimaginable: ornithocracy, peace, polyamory.

"As I love nature, as I love singing birds, and gleaming stubble, and flowing rivers, and morning and evening, and summer and winter, I love thee, my Friend." (Thoreau didnít capitalize thoughtlessly.)

"The wise are not so much wiser than others as respecters of wisdom."

A friend writes from China of an anecdote she was told by a young woman there about an elementary school lesson. A teacher took a group of girls into the bathroom and turned on two faucets, one with a slow drip, the other at full stream, then asked a girl to choose one. The girl selected the one at full stream, but to her surprise found she could only fill the glass half-way, no matter how many times she tried. Then she looked over and saw that the slow drip had filled the teacherís cup. Patience is the most important quality for success, the teacher said.

Critique this lesson.

Some things we choose. We breathe despite our will.

What can I do to be useful?

Exactly. This.

Tuesday

Overcast sky, mist in the air. A nice change from how itís been.

I drive north to the mouth of the Brule, passed by another eagle, park in an empty lot, and hike to a special place below falls where a big rock stands that is pocked with eye-socket-sized concavities.

Here I linger and play for a while in the spray, balancing angular red rocks on the branches of a stunted tree where a year ago I balanced chunks of ice.

RiviŤre brulťe?

Upstream the river spins downward into two deep rock cauldrons. Into one of them, the Devilís Kettle, water disappears with no apparent egress.

An egress is a female eagle. The little ones are called egrets.

Orange cedar needles, red pebble, white ice: Group portrait of some denizens.

Timeless time passes. I inhale deeply, then depart.

North beckons and I follow its siren call through Grand Portage Indian Reservation, Ojibwe land, and then... Yee ha! 13h00 -- Iím in Canadia. Or, more specifically, Minnetario.

A Canadian Border Patrol agent asks if Iím carrying meat or alcohol. You bet! "Any firearms or ammunition?" Yeah, why do you ask?

Then he waves me on in.

Some kinds of borders are good. Skin, for example. And yet...

An aptitude test might suggest an odd assortment of jobs for me: Phone operator, comedian, locksmith, bush pilot, ferry captain..

Librarian will do.

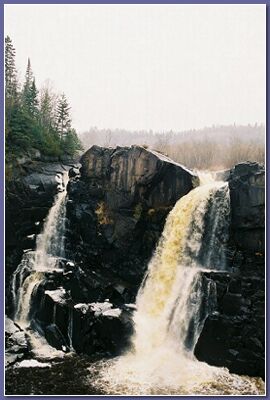

Gawd, it feels good to be here. I find my way along various paths to the Pigeon River High Falls, reaching closer perspectives than possible on the other shore, in fact standing on a rock right above the falls, obeying only laws of physics.

Gawd, it feels good to be here. I find my way along various paths to the Pigeon River High Falls, reaching closer perspectives than possible on the other shore, in fact standing on a rock right above the falls, obeying only laws of physics.

For a while I lose all sense of time again. When I return to my native country Iím uncertain how to answer the question "How long have you been in Canada?"

All my life?

Iím a border crosser at heart, relentlessly (if sometimes stupidly) transgressive. This raven-brained internationalist passes through, over, and around the hardest hearts, the highest walls, and the widest gulfs.

Look out. Rompe las fronteras.

As if we need ask a raven what nationality it is or require a passport from a pileated woodpecker.

"Ignorance and bungling with love are better than wisdom and skill without," Thoreau wrote in A Week.

I spend an hour or two before sundown on the Superior Hiking Trail from off the Arrowhead Trail north of the tiny settlement of Hovland, Minnesota. Itís a small happiness for me when the asphalt of Cook County 16 turns to gravel.

Across Carlson Creek, the forest is full of woodpeckers, downy, hairy, pileated. Hereís a black-backed woodpecker, a species I donít see where I live. It gladdens my heart.

At my feet: A puddle full of floating willow leaves, in perfect disarray.

I come to these wildish places to nurse my soul. I fill my lungs, my eyes, my ears, hungrily.

Thoreau again: "I can recall to mind the stillest summer hours, in which the grasshopper sings over the mulleins, and there is a valor in that time the bare memory of which is armor that can laugh at any blow of fortune."

Iím mending my coat of mail.

The world teeters in balance like a high-wire artist with a very long pole weighted on each end.

In winter, summer.

Diurnal night. Autumnal spring. Birth and death.

Two days ago I slipped on an icy rock. Even that was part of a balance.

In my daily life there are those whose absence is a profound presence.

As much as I despise disconnection, as long as I live, though I may walk in solitude, Iím not alone in my motivation, nor in my thinking, acting, seeing, and being. "The frontiers are not east or west, north or south," but wherever we front a fact, Thoreau asserts.

Today, after four days (or is it five?), Iíve finally slowed down. I forgot myself, got happily lost.

Back in town I visit the public library briefly before it closes at 5, peruse a map of Lake Superior in which south and north have been transposed (excellent!), and score three Russian pop culture magazines from a bin labeled "BRING SOME, TAKE SOME" or something like that.

Does Grandma Rae need another librarian?

This community has a pizza joint named Sven & Oleís and another eatery called South of the Border. The latter might not serve Mexican food.

My supper tonight: A tuna sandwich from one of the townís two chain restaurants. Tuna salad with tomatoes, green peppers, banana peppers, black pepper, black olives, and honey mustard on parmesan oregano bread. Cíest bon.

I donít want to leave this place. I caress the curve of its wooded hills, stroke the sinuous shore of Superior with my eyesí fingertips.

Can one have too much of this? I donít think so.

Wednesday

Time to pack my gear and head back to the world of higher human density.

Not yet dawn, I go north one last time (for now) and visit the Java Moose.

I remember just where I was when I first enjoyed the taste of coffee: Union Station Chicago, with a homeless guy who Iíd staked to a cup, into which he poured as much sugar and cream as it would hold.

Espresso says bitter can be good.

Once youíve acquired this taste, can you give it away?

I canít go back to the city without one more look at a river I love.

The turn from Highway 61 isnít marked onto the gravel road that goes to a place along this river.

For another spell of timeless time, before I say farewell, I walk on wet rocks along a wild stream, miraculous solid red earth into which perfectly round potholes have been drilled by natural forces.

"The finest workers in stone are not copper or steel tools, but the gentle touches of air and water working at their leisure with a liberal allowance of time." Thoreau, again.

"Who hears the rippling of rivers in these degenerate days will not utterly despair."

Say these words slowly:

Gentle touch.

Leisure.

Time.

I dip my bare hands into an icy pool.

Itís come to this.

Climbing Ktaadn, New England, May 2004

You Are Here, northern Minnesota, November 2003

Porcupine Mountains, Michigan's Upper Peninsula, May 2003

Baptism River, northern Minnesota, March 2003

Cairn Free, southern Utah, November 2002

Red Cliff, south shore of Lake Superior, May 2002