|

Rachmaninoff was born in the Vovgorod district of Russia in 1873, the year that Debussy became 10 years old and Liszt 61. Both his father and mother belonged to the upper class of Russian society

and had inherited large holding of land. The father, a military officer, was a charming person -- warm and loving toward his children but addicted to gambling and riotous living. The mother, a rather stern

person, seemed to do her duty somewhat coldly by her six children. The father’s behavior eventually caused the ruin of the family fortune, and Rachmaninoff’s parents had to sell their last estate and

move to St. Petersburg (now Leningrad) the year that Sergei was nine years old -- in 1882. A short time later the parents separated, the children stayed with their mother. The boy’s extraordinary

musical gifts had already been discovered and encouraged by good training, so that he received a scholarship at the St. Petersburg Conservatory shortly after the family moved to that city.

Unfortunately his motivation at that time didn't match his talent, and he failed to take his work very seriously.

His mother, concerned

about his further education, consulted his older cousin, Alexander Silori, who had just returned from a period of study with Liszt and was beginning his career as a piano virtuoso. Silori said that he would

recommend the boy to Nicolai Zverev, who had been his own teacher, and urged the mother to send her son to Moscow to work under the strict discipline of Zverev, who taught gifted young pianists in the lower

levels of instruction at the Moscow Conservatory. A few students lived in Zverev’s home, had their

lessons there, and had their practice supervised by the professor and his sister. Rachmaninoff went to the Zverev house in the fall of 1885 when he was 12, and lived and

studied there for four years. While under Zverev’s tutelage he not only developed his pianistic ability through expert training and well-directed practice, but he also heard the

extraordinary series of historical recitals of keyboard music given by Anton Ruberstein and became acquainted with many important Russian musicians, among them Tchaikovsky. When Rachmaninoff left the Zverev house

and entered the upper level courses at the Moscow Conservatory he studied piano with Silori, counterpoint with Taniev, and composition with Arensky in a class that

included Alexander Scriabin. Rachmaninoff graduated front the conservatory a year earlier than most students--at the age of 19--and was given a rarely awarded “great gold metal” of

the conservatory, having finished with highest honors in both piano and composition. lived in Zverev’s home, had their

lessons there, and had their practice supervised by the professor and his sister. Rachmaninoff went to the Zverev house in the fall of 1885 when he was 12, and lived and

studied there for four years. While under Zverev’s tutelage he not only developed his pianistic ability through expert training and well-directed practice, but he also heard the

extraordinary series of historical recitals of keyboard music given by Anton Ruberstein and became acquainted with many important Russian musicians, among them Tchaikovsky. When Rachmaninoff left the Zverev house

and entered the upper level courses at the Moscow Conservatory he studied piano with Silori, counterpoint with Taniev, and composition with Arensky in a class that

included Alexander Scriabin. Rachmaninoff graduated front the conservatory a year earlier than most students--at the age of 19--and was given a rarely awarded “great gold metal” of

the conservatory, having finished with highest honors in both piano and composition.

From his early maturity to the middle

of his live Rachmaninoff had a variety of experiences as a free artist, making the best of opportunities, and struggling with personal problems. His music was published almost as soon as he graduated from the

conservatory, partly on the strength of Tchaikovsky’s enthusiasm for it, and he continued to compose while earning a rather insecure living as an accompanist, piano soloist, and conductor. His one-act opera  Aleko, written as a final examination in composition at the

conservatory, was produced by the Bloshoi Opera in 1893 and was praised by Tchaikovsky who heard the first performance. The friendship and encouragement of the older man meant a great deal to

the 20-year old Rachmaninoff, but the premiere of his opera was a little more then six months past then Tchaikovsky died at the age of 53. Aleko, written as a final examination in composition at the

conservatory, was produced by the Bloshoi Opera in 1893 and was praised by Tchaikovsky who heard the first performance. The friendship and encouragement of the older man meant a great deal to

the 20-year old Rachmaninoff, but the premiere of his opera was a little more then six months past then Tchaikovsky died at the age of 53.

In 1895 Rachmaninoff started to compose his first symphony, a work he hoped would enhance his growing reputation, but when the symphony was played for the first time in 1897 in St. Petersburg the

critics were merciless. They didn't realize that, in part, their impression of the work was a result of inadequate rehearsal and poor performance. Rachmaninoff was so discouraged by this fiasco that he

was depressed for months. He refused to have the work repeated under more favorable circumstances; indeed it was never played again during his lifetime. Though his fame was growing, and he was invited to

London to play and conduct his music, he continued to brood over the disastrous premiere of his first large work for orchestra alone. He had begun to work on his second piano concerto, scheduled for a

first performance in London the following season, but had reached in impasse and found himself unable to continue an excellent beginning. A friend suggested he counsel Dr. Nicolai Dahl, a physician and

amateur musician who had treated emotional illness successfully with suggestion and hypnosis. He began to see Dr. Dahl daily in January of 1900. A few months later his artistic impotence was cured, and he was able to finish the ever-popular C minor concert which he dedicated to Dr. Dahl. to finish the ever-popular C minor concert which he dedicated to Dr. Dahl.

The year 1902

marked a major change in his life because in that year, when he was 29, he married his cousin, Natalya Satina. A year later their first daughter was born. He conducted

at the Bolshoi Opera from 1904 to 1906 while working on two operas of his own, but unsatisfactory production conditions at the opera house and the political unrest

following the 1905 revolution led him to move with his family to Dresden where he was better able to work on new compositions. In 1909 he came to the United States to play and conduct his music, particularly the

new third piano concerto which he played with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under Walter Damrosch. While in the United States he was offered the conductorship of the Boston Symphony orchestra which

had become vacant, but he refused. After his experience in the United States he returned to Russia to continue conducting, visited England again to play and conduct,

and had a brief stay in Rome in 1913. In spite of the advantages of living in Germany or Italy the Rachmaninoff's preferred to make their home in Russia.

The Russian revolution of 1917 led to the

greatest change of all in the life of the Rachmaninoff family. They were in Russia at the time of the Czar’s abdication and the resulting political upheavals. While the turmoil was at its height, Rachmaninoff

received an invitation to play recitals in Sweden, with the likelihood of repeating them in other Scandinavian countries. Unsure of what the future might hold in Russia, he obtained a permit to leave the

country for the performance and to take his family with him. One cold night, just before Christmas in 1917 the Rachmaninoff's crossed the border of Russia to go through Finland to Stockholm. They were

never to return to their homeland. Their only possessions were on their backs or in their luggage; everything else they owned, including their beautiful estate at Ivanokva, had  been confiscated by the communist authorities. been confiscated by the communist authorities.

Rachmaninoff was in debt and had a wife and two little

daughters to provide for. He decided that playing was the best way he could provide a livelihood for his family and set about becoming a piano virtuoso. He was 45 years old, his technique was

rusty, and his repertory limited, since up to that time his public performances had most often been of his own music. But he immediately began to prepare for a different kind of life and let it be known

that he wanted engagements as a piano recitalist. This was the beginning of almost 25 years of the suitcase existence of a solo musician. Enticing offers soon came from the United

States, so he crossed the Atlantic a second time, arriving in New York with his family just as the first World War came to an end. Since they were afraid to return to Russia the family led a rather nomadic

existence. Sometimes their home was in New York, sometimes Dresden, sometimes a suburb of Paris.

As an international concert artist Rachmaninoff usually accepted engagements in the fall and early winter

in Europe and on the American continent in the late winter and early spring. Travel by train and ocean liner was time-consuming and exhausting, and there was always the necessity of practicing. He accepted

a few invitations to conduct his own orchestral works but again refused to become the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and rejected a similar offer from Cincinnati. There was now no time nor

energy for composition except during summers, when the concert season was over, and his practice time could be reduced to a minimum. In 1931 the Rachmaninoff's bought property near Lake Lucerne in

Switzerland and built a home there. The summers seemed idyllic in these beautiful surroundings, especially when they could have expatriate countryman join them for all-Russian weekends or week-long

parties. The family finally sold their home in Switzerland and, after a summer in California, bought a new home in Beverly Hills. Because of recurring health problems Rachmaninoff had decided that the season

of 1942-1943 would end his Concertizing.

He was able to carry out only part of a planned tour; his recital in Knoxville Tennessee, in February of 1943 was the last time he played. The remainder of the

Tour had to be cancelled, and he returned to California where he died of cancer a few days before his 70th birthday. He had become a citizen of the United  States shortly before his death. Just as there are different evaluations of Rachmaninoff the pianist

and Rachmaninoff the composer, there were apparent contradictions between the man and the artist. States shortly before his death. Just as there are different evaluations of Rachmaninoff the pianist

and Rachmaninoff the composer, there were apparent contradictions between the man and the artist.

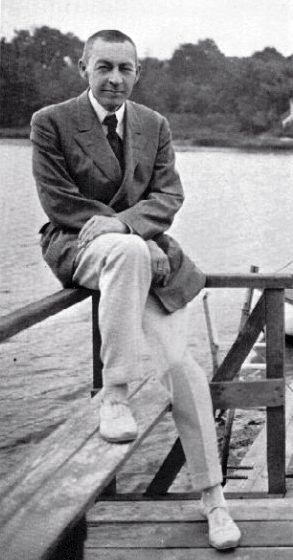

Rachmaninoff had the reputation of being a cold person - one whose thoughts and

feelings were hidden behind a mask. He avoided publicity and interviews if at all possible. He was slow to speak and notably stingy with words. When he walked on a stage

to play a concert -- a tall, gaunt, solemn man with rather Mongolian features and the haircut of a convict--his demeanor was indeed austere (Stravinsky once characterized him as a

"six-and-a-half-foot-scowl.") For a great deal of his life he was in ill health and suffering from neuralgia. He never felt comfortable expressing himself in English, and with strangers, or when

he was in public, he usually felt ill at ease. Friends who saw him at a party when he was feeling well and speaking Russian found him warm, witty, and bubbling with laughter and

high spirits. Similarly, in a recital, after he began to play, one had a very different impression listening to the music he produced. Absolute technical perfection was the rule, but in addition,

his tone was sensuously beautiful, his phrasing elegant and free, and his rhythms incisive but flexible. In his playing as in his compositions the man behind the mask was revealed as a sensitive, outgoing person.

Taken from “Rachmaninoff Selected works for the piano” 1985 Alfred Publishing Company. Murray Baylor, Editor.

|