Dotto

Written August 16, 2000

Revised November

9, 2005 and July 9, 2008

|

My involvement with broadcasting goes all the way back to the end of the Golden Age of Television: the quiz show scandals of the late 1950's. I was an observer at one of those rigged shows. It was July of 1958, and time for the annual vacation trip by car for our little family: my father, my mother, and my 11-year-old self. (That's my mother with me on the right, as we were being surprised by my father with the camera.) A tour of Washington, D.C., began the trip. Later we continued up through Massachusetts and as far as Nova Scotia, then returned for a few days at a lake in Rangeley, Maine. |

|

|

In between, we visited my uncle in New York. Ralph Buckingham was a vice president of the Whitman Publishing Company, part of Western Printing, publishers of the Little Golden Books for children. He had spent most of his career in Racine, Wisconsin, but in the late 1950's he worked in New York City. He and his wife Esther lived in an apartment in suburban Larchmont, New York; each day, he would take the train south into the city to his office at 415 Madison Avenue. |

|

To entertain his visitors for the morning, Uncle Ralph had obtained free tickets to a live TV show, something that none of us had ever seen in person. The program turned out to be the daytime version of the game show Dotto.

|

|

(These tickets, from Mark Evanier's informative website, are not for Dotto but for a different game show that had been televised five years before from the same Manhattan studio. As a boy like me, Evanier also was in a game-show audience; he recalls his experience here.) |

Dotto was quite popular at the time. It was actually seen on two different networks. There was a nighttime version on NBC (I think at 7:30 PM one night a week) and a daytime version five mornings a week on CBS. The latter had debuted earlier in 1958 and within five weeks had become the highest-rated daytime show in the history of television. And that was the show we were going to see!

|

|

|

The game was based on the familiar connect-the-dots puzzles. Beside each contestant was a large white panel with scattered dots. Host Jack Narz would question the contestant. In response to correct answers, a hidden stagehand would cause lines to magically appear on the panel, eventually forming a picture. When the contestant figured out what the picture was going to be, she won. (Most of these images are from a 1991 American Experience documentary about the scandals.)

Live from New York!

My parents and I took a cab to the midtown Manhattan address indicated on the tickets. After half a century, I've forgotten that address, but research identifies it as CBS Studio 62 (the Biltmore Theatre) at 261 West 47th Street.

In those waning days of live TV, New York was still a major production center, and CBS had many facilities scattered around town. Like most, Studio 62 was a small theater.

We were seated about half an hour before airtime. Technicians and talent were moving about the stage, making preparations.

Since the show was televised only in black and white, I was mildly curious to discover the actual colors of the set. They turned out to be muted browns, grays, and pale blues.

Downstage right was a white telephone on a little pedestal. (In those days one rarely saw a telephone that was not black.) It would be used to call a viewer, who would then have a chance to win a prize. The show was scheduled to open with a teaser for this feature, with the announcer saying something like "Today! Someone in America will receive a call that could be worth . . ." while the viewers gazed at the fateful phone.

Actually, it wasn't only the phone that they saw; it was an effect that I now know as a "box wipe." A somewhat smaller shot of the phone was inset into a full-screen shot of a map of the United States. The director set up this opening effect early. It must have been on the studio monitors for ten minutes before we finally went on the air live. (I suppose that without color bars, they had nothing better to put on the monitors. But I wonder now why they weren't worried about holding the camera stationary on a single shot that long, because the image of that white phone might permanently burn into the camera tube.)

|

On the air, standing next to mailbags full of postcards, the show's announcer found the lucky card and handed it and the white telephone to Narz, who talked to the viewer.

Below, the

rather cheesy map indicates that this particular call was not

"long distance." |

|

|

|

|

The host also touted the products of the sponsor, Colgate-Palmolive, which were prominently featured in the set design.

|

|

|

At that time, TV shows were controlled by their respective sponsors, who made almost all the decisions. But after the scandals, networks or independent producers took control, and the sponsors were reduced to merely buying part of the commercial time within the shows.

Our Role

Before going on the air, the warm-up man had instructed the studio audience that we were not expected to be quiet as mice during the broadcast. On the contrary, we were to ooh and aah loudly whenever merchandise prizes were shown, much as the audience of The Price Is Right (then as well as now) goes crazy at the prospect of a contestant winning a Brand New Car!

And, although we weren't supposed to shout out the answer, we were instructed to murmur loudly whenever the connect-the-dots picture started to resemble something recognizable. My parents and I felt a little foolish doing this — I remember exchanging a giggling glance with my mother — but we dutifully stage-whispered gibberish at the proper times.

|

The warm-up man told us that if the show ran short, it was possible that the cameras would be turned around and focused on us for the final few seconds. But that didn't happen. (This audience is from another high-rated quiz show of the era, The $64,000 Question.) |

|

Dotto's half hour ran its course, contestants won fabulous prizes to our applause, and soon it was over. We headed back to Larchmont, happy to have played our small part on national television.

The Start of the Scandals

Already, contestants on other programs had been claiming that the games were rigged. One of them was Herbert Stempel from NBC's Twenty-One. As dramatized in the 1994 movie Quiz Show, Stempel claimed that Charles Van Doren, an assistant professor at Columbia University, had cheated during his winning run in early 1957. The producers of all the quiz shows had denied the charges, and the public paid little attention.

But what happened on daytime Dotto in that summer of 1958 couldn't be ignored.

|

One day, in the very studio we had visited a few weeks before, new champion Marie Winn was welcomed back to the show. Marie was a college student who would graduate in 1959 — from Columbia, where Van Doren was still teaching. Another interesting fact is that she later became a successful author of such books as The Plug-In Drug (1977), about television's affect on children, and Red-Tails In Love (1998), about hawks in Central Park. I have more pictures of her on the show here. |

|

Dotto's producers must have wanted to make sure that this intelligent, attractive coed would be continue to be a winner.

Before coming onstage, she had perused a small notebook in the green room. Then she was summoned to make her entrance.

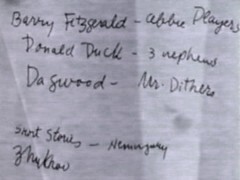

A standby contestant, Edward Hilgemeier Jr., remained behind, waiting for his chance. He couldn't resisted looking at the notebook (below left) that Marie had been studying. There were answers in it, and they were the same answers that she was giving on the air at that moment (below right)!

|

|

|

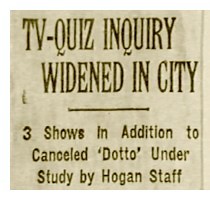

Realizing that she had been given an advantage — and that he himself hadn't — Hilgemeier took the incriminating notebook straight to the prosecuting attorneys. The word got back to CBS. Faced with hard evidence, the Dotto producers admitted that contestants had been given "some help." After the broadcast of August 15, 1958, the network abruptly canceled the show without explanation.

When

the story came out in the newspapers, my father remarked that he had

suspected that the game might not be on the level. During the

half-hour before air, he had noticed the host of the show in a

lengthy conversation with one of the contestants in an upstage corner

of the set. Going over the answers, perhaps? I thought it

unlikely that they would do this in full view of the studio audience,

but one never knows.

When

the story came out in the newspapers, my father remarked that he had

suspected that the game might not be on the level. During the

half-hour before air, he had noticed the host of the show in a

lengthy conversation with one of the contestants in an upstage corner

of the set. Going over the answers, perhaps? I thought it

unlikely that they would do this in full view of the studio audience,

but one never knows.

The scandals spread through 1959, when Van Doren confessed his role and resigned from the university. Many programs were canceled amidst public indignation. Although some game shows would continue, the big-money quizzes would not come back until Who Wants To Be a Millionaire? became a ratings sensation for ABC forty years later.