The Seoul Cypher

Written April 15, 2004

Late in the summer of 1988, I embarked on the longest journey of my life, in terms of both distance and time away from home.

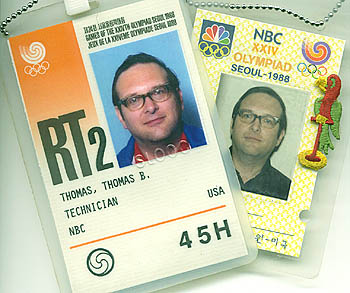

It was the first time that I needed a passport. Professionally, it marked my first exposure to the latest type of character generator. And it resulted in a first-class professional honor.

|

|

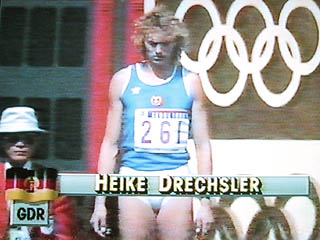

According to a preview in Time magazine, we freelancers were among a total of 1,100 NBC staffers who would be involved in the biggest remote in NBC Sports history. It was the network's first Olympics since 1964.

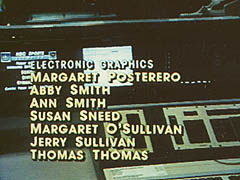

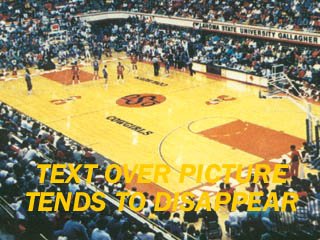

The 30 of us who were Chyron operators would have to learn how to run a brand-new graphics machine, the Sports Cypher, made by the British company Quantel.

|

Thursday, August 25, 1988 Yes, Seoul should be quite an experience; but maybe not the same sort of experience that you had when you visited Japan as a high-schooler. For you, becoming acquainted with a different culture was the whole point of the trip. My purpose will be to help in producing 179½ hours of American television. So I won't be interacting much with Koreans; instead, I'll be with NBC people all the time. Starting next week, we'll work seven days a week in TV trucks shipped over from the States or in our specially-built Broadcast Center. American food will be provided. NBC drivers will shuttle us around the city in vans. When we're off duty, we'll stay in the NBC section of the specially-built Press Village. Heavy security will keep out anyone who doesn't belong. We'll be in Seoul to work, with few if any days off. It doesn't bother me that I won't see much of the "real Korea." I feel a little uncomfortable in foreign lands, like New York City or Canada. I feel like an outsider, which of course I am. Actually, those are the only foreign countries I've visited (New York City and Canada). At least they're a lot like the United States. Except for Quebec, where all the signs and much of the conversation are in French; but I'm getting used to that, from visiting Montreal for baseball telecasts. After a month in Korea, maybe I'll even have developed a taste for kimchi. We'll see. |

My journey to Seoul took a full week. On Friday, August 26, I left my car parked at my apartment, and my father dropped me off at the Pittsburgh airport. I took a 9:45 am flight to Houston, where I worked two Pittsburgh Pirates games for KDKA-TV. On Sunday, I flew from Houston to Cincinnati for three more Pirates telecasts Monday through Wednesday.

|

|

Finally, on the morning of Thursday, September 1, I left Cincinnati bound for Portland, Oregon, and then for Seoul, arriving there in the evening of Friday, September 2. Since these final two legs would require more than 18 hours and cross ten time zones plus the International Date Line, I decided to try to minimize jet lag by readjusting my mental clock — if not my body clock — during the course of the trip. |

To gain 14 hours, I could have tried to make my mental clock run 35% faster (54 fake hours in 40 actual hours).

But we humans tend to distort time in the opposite direction, staying up past our bedtimes and getting up late the next morning. I decided it would less disruptive to first "cross the Date Line" by setting my mental clock ahead by a full day, and then to let it run 25% slower (30 fake hours in 40 actual hours).

Click here for more pretense that one day can be more than 24 hours.

I kept my wristwatch on real time, of course, but I had another virtual clock (actually a conversion table on an index card) that I set back 15 minutes every hour. Let's call that Fake Standard Time, or FST. I pretended that the time of day on this very long Thurfriday was actually FST.

|

. |

EDT |

FST |

Korea |

|

Set "FST" ahead one day |

10 pm Wed |

10 pm Thu |

Noon Thu |

|

To bed in Cincinnati |

Midnight |

11:30 Thu |

2 pm Thu |

|

. |

2 am Thu |

1 am Fri |

4 pm Thu |

|

. |

4 am Thu |

2:30 Fri |

6 pm Thu |

|

Arise in Cincinnati |

6 am Thu |

4 am Fri |

8 pm Thu |

|

. |

8 am Thu |

5:30 Fri |

10 pm Thu |

|

Flight departs |

10 am Thu |

7 am Fri |

Midnight |

|

. |

Noon Thu |

8:30 Fri |

2 am Fri |

|

Arrive Portland 11 am PDT |

2 pm Thu |

10 am Fri |

4 am Fri |

|

Depart Portland 1 pm PDT |

4 pm Thu |

11:30 Fri |

6 am Fri |

|

. |

6 pm Thu |

1 pm Fri |

8 am Fri 8 |

|

. |

8 pm Thu |

2:30 Fri |

10 am Fri |

|

Halfway across Pacific |

10 pm Thu |

4 pm Fri |

Noon Fri |

|

. |

Midnight |

5:30 Fri |

2 pm Fri 2 |

|

. |

2 am Fri |

7 pm Fri |

4 pm Fri |

|

Arrive at Seoul airport |

4 am Fri |

8:30 Fri |

6 pm Fri |

|

Customs check |

6 am Fri |

10 pm Fri |

8 pm Fri |

|

Arrive at Press Village |

8 am Fri |

11:30 Fri |

10 pm Fri |

|

To bed |

10 am Fri |

1 am Sat |

Midnight |

|

. |

Noon Fri |

2:30 Sat |

2 am Sat |

|

Back in sync |

2 pm Fri |

4 am Sat |

4 am Sat |

|

Elapsed time |

40 hours |

30 hours |

40 hours |

Upon

arriving in Seoul and clearing customs, we checked into our rooms at

the Press Village. This was a complex of multi-story buildings,

located adjacent to the athletes' Olympic Village. After the

Games, these buildings would become apartments.

Upon

arriving in Seoul and clearing customs, we checked into our rooms at

the Press Village. This was a complex of multi-story buildings,

located adjacent to the athletes' Olympic Village. After the

Games, these buildings would become apartments.

For 32 days, my home was room 2A (a single bedroom) in unit 202 of building 124 (highlighted here in blue). We entered and exited the Press Village through the accreditation center A. Sometimes we ate at the press cafeteria B.

One of the leaders of our graphics team, Howard Zryb, recalled:

The brochure described the accommodations and amenities at the Press Village as equal to or better than that of a hotel. However, the hotel they surveyed was located in Tijuana. The bedsheets in the Press Village were paper, the towels non-existent, safe deposit boxes and closet space inadequate.

However, the Press Village had its fun moments, too. And that's the true spirit of the Olympics. After all, we are all amateurs.

Another

souvenir was this half-inch-square NBC pin.

Another

souvenir was this half-inch-square NBC pin.

Chong

refused. He told the newspaper, "I found the overall

design and words of the sweatshirts highly critical of our country

and the national flag, Taegukki."

Chong

refused. He told the newspaper, "I found the overall

design and words of the sweatshirts highly critical of our country

and the national flag, Taegukki."