Telemeetings

Written

September 12, 2004

Last

summer in New York City, I had an entire day set aside to get home

to Pittsburgh. So it was merely an annoyance when, after my

plane had taxied away from the gate at LaGuardia, the pilot announced

that air traffic was congested and we would not be allowed to take

off just yet.

During what turned out to be a two-hour wait on the tarmac, passengers were allowed to use their cell phones. The woman behind me called her office and determined that it would now be impossible for her to get to Pittsburgh in time to make her connection to Minneapolis. Thus, she would miss her meeting in Minneapolis that afternoon. She might as well return to her New York office and start preparing for the next day's meeting in Philadelphia. But unfortunately, she was stuck on the plane with the rest of us because we had already gotten in line for takeoff.

I began to wonder why she needed to go flying all over the country. Long-distance conversations by telephone have been possible for a hundred years now. E-mail and other technologies allow us to pass documents and other information back and forth. Why did her company have to spend hundreds of dollars to send her to Minneapolis in person, just to talk to a few Minnesotans for a couple of hours?

Perhaps face-to-face interaction is deemed essential. But there are other ways to achieve even this. Conferences can be held via television.

In the past, such teleconferences have been complicated and expensive to arrange — too complicated and expensive for everyday use. But lately it's become more economical to send compressed TV pictures around the country. If we could make setting up a teleconference no more difficult than arranging a conference call on the phone, this technology could save a lot of money and fuel that's now being used for travel.

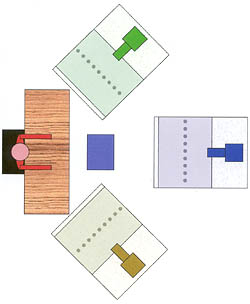

Suppose that every office building had a small studio for telemeetings. Suppose that all such studios were connected to a single nationwide dial-up network. And suppose that all the studios were built to a standard plan, such as the one shown below.

|

An executive in Fresno could simply go downstairs to his studio and sit at the desk. On the opposite side of the desk is a computer monitor that will display documents for all the participants to view. With a few mouse clicks, he could open circuits to as many as three additional offices.

Mr.

Fresno might assign Boston to appear in front of him in the

"window" indicated by the blue dotted line. For a

bigger meeting, a Chicago client might be in the green window to his

left, and a San Diego supplier in the tan window to his right. |

|

|

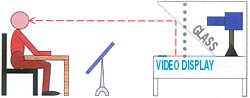

The

profile drawing reveals that a "window" is actually a

tilted sheet of glass in which Mr. Fresno sees the reflection of a

60-inch TV monitor, placed flat on a tabletop and displaying Mr.

Boston's life-sized face and upper body. Also mounted to the

table, looking through the glass, is the camera that will transmit

Mr. Fresno's image to Boston. This arrangement allows Mr.

Fresno to simultaneously look directly at both Mr. Boston's image and

the Boston-bound camera. |

|

|

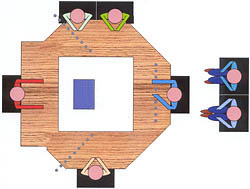

If Mr. Fresno turns 45° to his left to see Chicago, he'll be looking at the green camera. The folks in Chicago will see that he's looking at them, and the folks in San Diego will see that he's turned 90° away from San Diego to speak with Chicago.

The

conferencing software hooks up the other sites accordingly.

For example, Mr. Boston will have a computer monitor in front of his

desk with Fresno in the window beyond, San Diego on his left, and

Chicago on his right. |

|

|

|

Here's

how Mr. Fresno perceives the meeting, through his three dotted-line

"windows." Notice he can see two conferees at

the Chicago desk, while Mr. Boston has a couple of assistants sitting

behind him. As many as 12 people can participate in a

telemeeting like this. |

|

|

They

all seem to be sitting around the same four-sided table, looking

each other in the eye and exchanging glances in a natural way.

All that we're missing is a virtual handshake. |