Ten Key

Written

July 28, 2008

The most valuable class I took at Richwood High School in the 1960s was not in a traditional academic subject. I think I actually learned more from outside reading.

No,

my most valuable class was typing, as taught by Mrs. Lucille Powers

(right). In this course, which lasted only one semester, I

learned how to touch-type up to 90 words per minute.

No,

my most valuable class was typing, as taught by Mrs. Lucille Powers

(right). In this course, which lasted only one semester, I

learned how to touch-type up to 90 words per minute.

Nowadays this skill applies not so much to old-fashioned typewriters as to computer keyboards. Therefore, it's useful in my job of preparing graphics for television sports.

Also in the 1960s, while hanging around my father's Chevrolet-Oldsmobile dealership, I learned how to "touch-type" numbers on a keypad with ten keys. The ten-key numeric keypad was a fairly recent innovation.

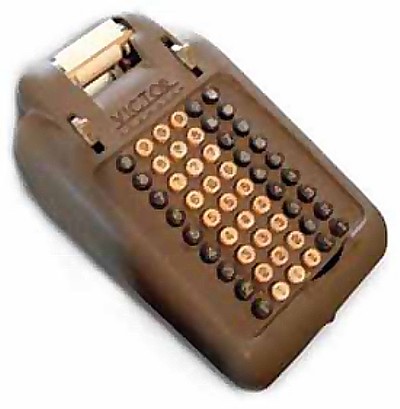

In the 1950s, the dealership had used adding machines something like the one below.