![]()

The

Very Wide Screen

Written

October 25, 2005

|

The Thomas family, my parents and I, were seated in a theater in central Ohio one afternoon. CBS radio newscaster Lowell Thomas — no relation — was addressing us from appeared to be an ordinary motion-picture screen. |

|

I've forgotten exactly when and where this took place. A good guess would be the spring of 1961 at the RKO Grand on East State Street in Columbus, across from the state capitol. A few months before, the Grand had been specially remodeled to become only the 11th theater in the nation equipped to show a feature called This Is Cinerama.

|

|

Despite the fact that this movie was now nine years old, curious Ohioans still wanted to see what it was all about. |

|

Attending This Is Cinerama was an event, complete with reserved-seat tickets. As we entered the lobby, we were handed a program, as though we were at a Broadway play. The program explained that this movie had been photographed by a giant camera, using three lenses and three reels of film. |

|

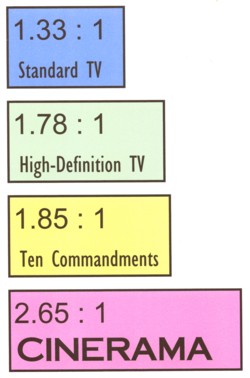

Some sources give different numbers for Cinerama's aspect ratio, mostly between 2.59 and 2.77.

Nowadays, IMAX theaters expand this concept into a second dimension, using spherical screens that are very tall as well as very wide. But our peripheral vision extends only to the sides, not above and below, so we never see all of an IMAX image at once.

|

|

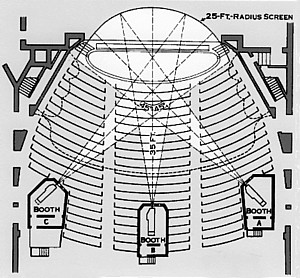

Now we were going to see it projected from three synchronized projection booths onto a huge cylindrically curved screen, 75 feet wide and 28 feet tall. That's an "aspect ratio" of 2.65 to 1. An audience member sitting in the center of the arc — front row center in this diagram — would find his peripheral vision filled by the screen, with a field of view 146° across. |

|

Until 1952, when this film was released, both movies and TV used an aspect ratio of 1.33 to 1. (Today's HDTV has a wider ratio of 1.78 to 1.) This Is Cinerama showed that big screens could give movie theaters an advantage over their emerging competitor, television. Other innovators in Hollywood quickly developed other, more practical widescreen techniques, using single cameras with special anamorphic lenses. For example, in 1956 I saw The Ten Commandments with its 1.85 to 1 aspect ratio. While not as overpowering as Cinerama, these pictures were still far better than TV. By 1961, therefore, I was already familiar with widescreen movies. But the original Cinerama promised to be the ultimate experience. |

|

The house lights went down, and the huge 100-foot-wide burgundy curtain opened partway — about 40 feet — to reveal a movie screen. The image of Lowell Thomas appeared, in black and white and the standard 1.33 to 1 ratio. He described the invention of motion pictures. He described the improvements that had been made over the years. And now, he said dramatically, "This . . . is Cinerama!"

The curtain opened the rest of the way to reveal the full 75-foot width of the screen, which was immediately filled with a colorful scene. A scene of what? For a moment, we in the audience weren't sure. But then, hearing a click-click-click, we realized that we were on a roller coaster slowly climbing to the top of its track.

We had been warned about this sequence. We groaned, sucked in our breath, and held onto the armrests. The roller coaster reached the top and began its wild dash downward. We stared at the track rushing toward us. Structural supports flashed past us on the left and right edges of our vision, and we heard the screams of our fellow passengers all around us. Yes, this Cinerama was realistic!

The

process wasn't perfect. The printed program explained

that, to minimize any defects in registration, each of the three

projectors was designed to blur the left and right edges of its

image. But we were still distracted by the visible seams

between the images: two fuzzy vertical bands, one-third and

two-thirds of the way across the picture. Also, oblique lines tended

to change direction as they crossed the boundary from one lens's

perspective to another's. And the colors didn't always match.

For more about Cinerama, you can go to various websites that were the source of some of this article's data and all of the pictures. Two examples are sites by Leonard Maltin and by Hollywood Theatre.

The movie had no plot. It was sort of a travelogue, designed to show off the capabilities of the technology. This was especially true of a sequence shot from a plane flying low through the Grand Canyon, banking and turning close to the canyon walls to the accompaniment of patriotic music.

Cinerama also greatly advanced the sound quality of motion pictures. Introduced at a time when all other movies were monophonic, Cinerama was not merely stereo, it was multichannel. In today's terminology, it featured 7.0 channels of audio, with five speakers spaced at intervals behind the screen plus two more channels for surround sound. These seven sound tracks came from a fourth "projector" playing magnetically-coated film.

|

After the intermission, Thomas's voice returned to say, in effect, "We're not going to show any pictures for the next couple of minutes. We'll leave the curtain closed so that you can focus your attention on the quality of Cinerama's sound. Just listen to this symphony orchestra." And it seemed as though there were actual live musicians in the orchestra pit. |

|

I was only in eighth grade at the time, so I might be wrong, but I don't think I've ever heard more realistic music reproduction.

But as it turned out, the process was impractical for feature films. One epic movie, How the West Was Won, was filmed in Cinerama in 1962. However, director John Ford and others found that the field of view was too wide for narrative picture-making. Such essential cinematic techniques as closeups and rear-screen projection just didn't work right, and it was difficult to position the actors. Also, the triple-barreled camera was awkward and heavy.

I never saw How the West Was Won in a theater. But I did see parts of it on television much later, around the turn of the century. NBC-TV aired the lengthy movie in prime time.

|

That night, to accommodate the wide aspect ratio, they left half of the TV screen black. Only a strip across the middle was used. It was an extreme example of the technique called "letterboxing." This sort of picture hardly conveys the impact of the Cinerama I had seen 40 years before. |

|