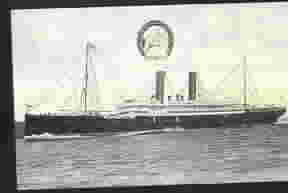

Italia, Anchor Line, taken

by my Great-grandfather from Italy

Paying for the voyage

At the turn of the century, the price of the lowest

priced sterrage tickets were $25-35 depending on the port of embarkation. Since the price

of a ticket was often too expensive for the poor people remaining in Europe, it was often

sent back from the earlier arrivals to America. One ticket was equivalent to 2 or 3 weeks

wages and after room and board an immigrant might have 50/week to save.

Many emigrants travelled with someone from their town. The

support of people they knew was critical during the voyage and upon arrival.

Routes from Italy

Naples - Sicily - New York

Southern Italy, the source of most Italian immigrants had

two major departure points Naples and Sicily. People traveled from as far as Sicily to

depart on voyages from Naples. St. Angelo dei Lombardi and San Costantino Albanese are inland towns whose residents went

overland to Naples to go to America

Traveling out of rural areas to the port towns was

difficult since there were no cars and train service was only between major cities. Some

people came into the port towns on smaller boats for the transfer to major steam lines for

the oceanic voyage.

Routes from Ireland

Glasgow - Londonderry - New York

A couple of major points served as embarkation

points reached overland by emigrants. Cavan county is the most

southern county of Ulster of which Londonderry (in Northern Ulster) was the major Irish

port. Trains were not extensive in Ireland so people reached port cities by foot, horse,

and later car.

Routes from Poland

Gdansk - Hamburg - New York

Trains from major towns in the interior of Poland went

north to the port city of Gdansk or Danzig.

In addition to the steamship ticket, the trip required

assembling a large number of papers to be delivered to the American consulate in Warsaw.

Included were medical certificates, birth records, police records, statements from parents

if a minor, statements from local authorities proving lack of debts.

The consul sent an appointment and as long as you had a

affidavit from a close relative in the US proving that you wouldn't be a public charge, a

visa was issued for travel.

Emigrants on deck en route to America

Ships Manifest

The ships manifest kept track of all the

people on board and was the record keeping tool for arrival in the United States. The

manifest noted medical examinations if they took place before departure and had

information about every passenger on board. Shipping companies prepared the lists abroad,

rechecked at departure, and the lists were checked again upon arriving in the U.S.

The information was usually by class

starting with the first and second which were typically very small (under 30 poeple) on

these voyages and usually made up exclusively of Americans. The bulk of the manifest

covered the steerage class and became more detailed during the peak immigration years

after 1900. The steerage class could be as many as one thousand people on ships such as

the Kaiser Wilhelm II. Steerage is the below the waterline area named for its proximity to

the steering mechanism.

The following is information from the ships

manifest on the Italia arriving Apr. 20, 1909 from Naples.

Pasquale Pomarico, line 8

- Listed as traveling for the first time, this was apparently

not the first trip over since census records indicate that he came over first in 1892, 15

years earlier. Two children were born in Italy during that time indicating voyages back

and forth. These people were called "birds of passage" and typically arrived in

the spring and returned to Southern Europe by Christmas.

- Pasquale listed Francesco Pomarico, his uncle, living at 494 President in Brooklyn as his contact person.

Luigi Pomarico, line 12

- Luigi listed a different person, Donato Pomarico, as his

contact person. However, Donato was living with Francesco and family at 494 President at

the time. In 1898, Donato had used his brother Pasquale as his contact person.

Maddalene DiPiacere, line 7

- Miss DiPiacere was traveling from the same hometown as

Pasquale and his cousin Luigi. Unlike them, she was headed to Waterbury, CT with a

companion. The companion was from Torella dei Lombardi, a town near S. Angelo and the

birthplace of Pasquale, along with a very large group of people on the boat.

DiPiacere’s trip might have been one reason for Pasquale taking this particular

voyage. Based on other manifests, Waterbury was a popular destination for people from the

Sant Angelo dei Lombardi area. After 3 years in New York, Luigi appears in the directory

for Waterbury where he stayed for one year.

Steamship Lines

Before 1880, sailing ships still made the long trip across

but they took as long as 1-3 months to make the trip. Steam powered ships took over by

later making the trip in 8-14 days.

Several major steamboat lines such as Cunard and White Star plied the

North Atlantic during the peak years of this migration. The steerage class, taken by poor

travelers, was a money maker for the lines and additional boats were commissioned to

increase revenues along the route. The boats were steam powered and sometimes supplemented

by sails.

S.S. California taken by

another relative

The North Atlantic during the winter can be a treacherous

route as discovered by the Titantic. Steamship traffic increased in the summer months

although many of our ancestors arrived as late as early December. The voyage took

approximately 10 days from Italy.

Conditions Conditions

While far better than the slave ships of the same period,

the paid voyage was not an easy one. 10-15% of the people often died during the

voyage early in the 1800s. In 1819, the federal government tried to regulate the shipping

lines setting passenger limits, minimums of water and provisions and fined offenders.

Unfortunately, this law did not cover passengers in steerage.

Steerage passengers were required to carry their own food

for the voyage. Only after 1848 was cooked food required for steerage passengers as well.

The amount of time locked in the airless below deck area meant high exposure to contagious

diseases. With the change to steam powered ships later in the 1800s, the shorter transit

time meant reduced exposure to such contagions although the conditions were often little

improved. |