Adventure games follow the adventures of a player-controlled character and are story-based in that as the player progresses through the game a story unfolds. Progression is through solving puzzles. Such as taking an item to a certain place, finding and putting a number of objects together to create a new object that opens a door or allows access to a new area. The game character on the screen tends to be just an icon for the player to interact with the game world. The character graphic also lets the player know the location of the character he is controlling and what actions he is doing.

A possible precursor to computer adventure games was the adventure books. They existed for a time in parallel with the computer games, when computers were inaccessible to most people due to their expense. The player was given a choice of actions and then turned to the page with the result of his choice and this is the basic design of text adventures. Pure text adventure games are sometimes called Interactive Fiction.

The Text Adventures

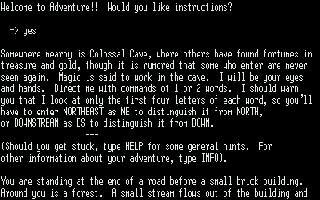

William

Crother, who worked for Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) in Boston developed

a purely text game called Colossal Cave Adventure to help keep in touch

with his children when he got divorced in 1976. Don Woods a graduate student

at Stanford University heard about the programme and downloaded a copy, and

got the original code from Crother after a mass emailing campaign on the fledgling

internet to track down his location. Woods increased the complexity of the

mazes and puzzles, and added Tolkien-esque elements. Written in Fortran it

was useable on a wide variety of computer systems and with its new name of

Adventure gave birth to a completely new genre.

William

Crother, who worked for Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) in Boston developed

a purely text game called Colossal Cave Adventure to help keep in touch

with his children when he got divorced in 1976. Don Woods a graduate student

at Stanford University heard about the programme and downloaded a copy, and

got the original code from Crother after a mass emailing campaign on the fledgling

internet to track down his location. Woods increased the complexity of the

mazes and puzzles, and added Tolkien-esque elements. Written in Fortran it

was useable on a wide variety of computer systems and with its new name of

Adventure gave birth to a completely new genre.

Adventure was text based with a narrative mentioning the player's situation. The Player was given a choice of several objects to resolve a challenge. He inputted his choice through strict noun-verb sentences. The computer recognised key words in the user's input and then outputted the resulting paragraph, to further advance the adventure.

In

1977, at MIT Marc Blank, Tim Anderson and Bruce Daniels were inspired by Adventure,

whose popularity had spread through the ARPAnet, to make their own game Zork.

Zork's parser set up interactions between objects, verbs, and locations, which

allowed players a much wider vocabulary than having to guess the exact name

of an object manipulate it. In 1979, Blank and other MIT students formed Infocom

and in 1980 in partnership with Personal software, Zork was published on the

first wave of personal computers including the Apple I. A new industry had

been born when Scott Adams took the game concept to home computing in 1979

with Adventure International and their first game, which was called Adventureland.

However, the sophistication of Zork's parser and the better gameplay it offered

meant that by 1983, eight of the games industry hottest titles were Infocom

text-adventures.

In

1977, at MIT Marc Blank, Tim Anderson and Bruce Daniels were inspired by Adventure,

whose popularity had spread through the ARPAnet, to make their own game Zork.

Zork's parser set up interactions between objects, verbs, and locations, which

allowed players a much wider vocabulary than having to guess the exact name

of an object manipulate it. In 1979, Blank and other MIT students formed Infocom

and in 1980 in partnership with Personal software, Zork was published on the

first wave of personal computers including the Apple I. A new industry had

been born when Scott Adams took the game concept to home computing in 1979

with Adventure International and their first game, which was called Adventureland.

However, the sophistication of Zork's parser and the better gameplay it offered

meant that by 1983, eight of the games industry hottest titles were Infocom

text-adventures.

The Graphic Adventures

Roberta

Williams, knew nothing about computers and was not even interested in them

but when her husband, Ken exposed her to Adventure, she decided to make her

own. Roberta sketched out the story and puzzles, and when her husband advised

her she would need something new to make it sell, she said she would like

to sketch pictures on the screen of what the characters were doing rather

than just describing everything in the game. Ken was a programmer for Informatics

and thought he could get something to work on his new and expensive Apple

II. Mystery House was developed in just a couple of months in 1979

and was the first graphic adventure as the text had accompanying on-screen

line Illustrations. The Williams marketed the game themselves on a shoestring

under the name of On-Line Systems. The orders came flooding in. Roberta took

hint calls in their home whilst she worked on a second longer game called

Wizard and the Princess, they found they had enough money to move to

the mountains and the fledgling company's name was changed to Sierra on-Line.

Roberta

Williams, knew nothing about computers and was not even interested in them

but when her husband, Ken exposed her to Adventure, she decided to make her

own. Roberta sketched out the story and puzzles, and when her husband advised

her she would need something new to make it sell, she said she would like

to sketch pictures on the screen of what the characters were doing rather

than just describing everything in the game. Ken was a programmer for Informatics

and thought he could get something to work on his new and expensive Apple

II. Mystery House was developed in just a couple of months in 1979

and was the first graphic adventure as the text had accompanying on-screen

line Illustrations. The Williams marketed the game themselves on a shoestring

under the name of On-Line Systems. The orders came flooding in. Roberta took

hint calls in their home whilst she worked on a second longer game called

Wizard and the Princess, they found they had enough money to move to

the mountains and the fledgling company's name was changed to Sierra on-Line.

Sierra

in 1984 was commissioned by IBM to develop Kings Quest as a showcase

for the powers of the newly released IBM PCjr, which then had a technological

impressive 16-colour palette, three-channel sound and 128k of memory. It was

the first game to support EGA colour cards. The hardware specifications allowed

Sierra to create a fully animated world with characters that could walk anywhere,

even around trees; music that played at all times and sound effects. This

set the standard for adventure games and even the latest offerings still have

the same basic design features. Sierra used a common interpreter called AGI,

which made their games portable across a variety of hardware platforms. They

later developed a programming language called SCI (Sierra's Creative Interpreter).

Although the PCjr with its non-user friendly tiny keyboard flopped, the Tandy

1000 sold in Radio Shack stores across America insured that the game was a

best-seller. The King's Quest series has sold more than 3 million copies,

making Roberta Williams one of the best-selling computer game designers in

the industry.

Sierra

in 1984 was commissioned by IBM to develop Kings Quest as a showcase

for the powers of the newly released IBM PCjr, which then had a technological

impressive 16-colour palette, three-channel sound and 128k of memory. It was

the first game to support EGA colour cards. The hardware specifications allowed

Sierra to create a fully animated world with characters that could walk anywhere,

even around trees; music that played at all times and sound effects. This

set the standard for adventure games and even the latest offerings still have

the same basic design features. Sierra used a common interpreter called AGI,

which made their games portable across a variety of hardware platforms. They

later developed a programming language called SCI (Sierra's Creative Interpreter).

Although the PCjr with its non-user friendly tiny keyboard flopped, the Tandy

1000 sold in Radio Shack stores across America insured that the game was a

best-seller. The King's Quest series has sold more than 3 million copies,

making Roberta Williams one of the best-selling computer game designers in

the industry.

Sierra with something they called Reality Role-playing started to merge role-playing and traditional adventure games. Police Quest: In Pursuit of the Death Angel (1987) started a long series and although very much a standard adventure with flat-side scrolling world, it tried to introduce role-playing elements such as simulating the actions of a real police officer. The last game in the adventure series Police Quest 4: Open Season (1993) used photos rather than drawings.

Sierra

in 1990 with King's Quest V: Absence Makes The Heart Go Yonder, changed

the command inputs from trying to guess what an item was called to a graphical

interface. The player manipulated objects by clicking on the graphic of the

object. Lucas Arts' The Secret of Monkey Island in 1990 is considered

one of the best ever adventure games. Ron Gilbert's humorous script permeated

the games plot and puzzles. It combined a list of text commands that could

be applied to the character or any object that could manipulated in the game.

The interface design of these two games set the standard for all future Adventure

games. The style of humour went back to Zork and was replicated in many following

adventure games such as the Leisure Suit Larry series which began in

1991, Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist (1993) Discworld (1995)

or The Feeble Files (1996).

Sierra

in 1990 with King's Quest V: Absence Makes The Heart Go Yonder, changed

the command inputs from trying to guess what an item was called to a graphical

interface. The player manipulated objects by clicking on the graphic of the

object. Lucas Arts' The Secret of Monkey Island in 1990 is considered

one of the best ever adventure games. Ron Gilbert's humorous script permeated

the games plot and puzzles. It combined a list of text commands that could

be applied to the character or any object that could manipulated in the game.

The interface design of these two games set the standard for all future Adventure

games. The style of humour went back to Zork and was replicated in many following

adventure games such as the Leisure Suit Larry series which began in

1991, Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist (1993) Discworld (1995)

or The Feeble Files (1996).

Multi-Media Adventures

Sierra with the adventure/edutainment game Mixed-Up Mother Goose in 1992 added multimedia elements. Sierra bought a company called Bright Star to gain the technology to allow speech to be synchronised with the lips of the animated characters. Games like Kings Quest VI released in 1992 used multi-media and had digitised actors' voices and a branching story line that used seven times as much script than would a linear story. Return To Zork (1993) used digitised film images of actors. However, it was not a traditional games developer that pioneered the use of the new multi-media technology.

Myst

published in 1991, was very much ignored by the mainstream games press and

it got poor ratings. Cyan was pretty much unknown for game development but

had developed The Manhole (1989), a children's edutainment product

which had being the first to use the new medium of CD-ROM. However, Myst was

highlighted by the mainstream media for its multimedia storytelling and striking

ray-traced images. Myst became an instant best seller and gained a reputation

as a radical game that successfully broke into the non-gamer's market. Myst,

in fact was a traditional cryptic adventure game. Its game-play was little

different from the original text adventures.

Myst

published in 1991, was very much ignored by the mainstream games press and

it got poor ratings. Cyan was pretty much unknown for game development but

had developed The Manhole (1989), a children's edutainment product

which had being the first to use the new medium of CD-ROM. However, Myst was

highlighted by the mainstream media for its multimedia storytelling and striking

ray-traced images. Myst became an instant best seller and gained a reputation

as a radical game that successfully broke into the non-gamer's market. Myst,

in fact was a traditional cryptic adventure game. Its game-play was little

different from the original text adventures.

Myst used a first-person perspective as found with RPG's but with beautiful static graphics. Interaction was with a mouse on various objects that caused an animation to occur. This was perfect for people just coming to terms with the Mac or Windows 95 interface. The story was surrealistic with a large environment to explore and appealed to adults getting acquainted with their first computer and game. This was very different from the zany character animation and item interaction that had been developed by adventure games such as Monkey Island. The sequel Riven had the same formula but with even better graphics but was not as successful, the technological appeal was only transitory. Myst and Riven together sold over 12 million units worldwide, and are amongst the best selling computer games in history. Myst proved that old genres such as the traditional adventure game can be given a new lease of life and can appeal to market outside that of traditional games players. The series was followed up by Myst III : Exile (2001) developed by Presto Studies which retained the same gameplay but used a 360 degree scrolling technology.

Sherlock

Holmes: Consulting Detective (1991) by ICOM Simulations, used 90 minutes

of motion video of Holmes interaction with other characters as he solved three

cases. Under A Killing Moon (1994) by Access software, used three CDs

with full motion video and photo-realistic scenes that form a 3D world which

gave the player full manoeuvrability. The player could even look for clues

underneath desks and chairs. The game included an online hint system (that

decreased the player's final score, the more the player used it). For the

first time famous actors and actresses came to the small screen. Marggot Kidder,

who played Lois Lane, from the Superman movies, had a role in the game.

Sherlock

Holmes: Consulting Detective (1991) by ICOM Simulations, used 90 minutes

of motion video of Holmes interaction with other characters as he solved three

cases. Under A Killing Moon (1994) by Access software, used three CDs

with full motion video and photo-realistic scenes that form a 3D world which

gave the player full manoeuvrability. The player could even look for clues

underneath desks and chairs. The game included an online hint system (that

decreased the player's final score, the more the player used it). For the

first time famous actors and actresses came to the small screen. Marggot Kidder,

who played Lois Lane, from the Superman movies, had a role in the game.

New Directions

Infogram's

Alone in the Dark, released in 1992, introduced 3-D graphics to the

adventure genre. This allowed the addition of action to the game as the character

fought with swords and fired guns in real time. Otherwise it was standard

stuff, escape from a haunted house by finding written clues and manipulating

the objects found in the house. I have heard some magazines call Tomb Raider

(1996), by Eidios, an adventure game. Tomb Raider certainly has evolved from

games like Alone in the Dark, and although it has an Adventure style story

line and CRPG style puzzles, it forms a new subgroup, the Action-Adventure.

Infogram's

Alone in the Dark, released in 1992, introduced 3-D graphics to the

adventure genre. This allowed the addition of action to the game as the character

fought with swords and fired guns in real time. Otherwise it was standard

stuff, escape from a haunted house by finding written clues and manipulating

the objects found in the house. I have heard some magazines call Tomb Raider

(1996), by Eidios, an adventure game. Tomb Raider certainly has evolved from

games like Alone in the Dark, and although it has an Adventure style story

line and CRPG style puzzles, it forms a new subgroup, the Action-Adventure.

Westwood's

Blade Runner, released in 1997 used a radical dynamic story, in which

the game randomly decided which characters are the replicants. Characters

have their own agendas and may turn up in a scene on a randomly determined

course of action and the player can decide to either terminate or join the

replicants. This was supposed to make the game replayable but in reality did

not give sufficient difference to the game to hold sufficient interest for

a second rerun. The player interacted with characters by choosing one of four

conversation modes and then watches a movie sequence. This is no different

from the traditional method of presenting a sensible reply and three silly

responses. The game to reach a larger mass market not only used a film license

but simplified the gameplay.

Westwood's

Blade Runner, released in 1997 used a radical dynamic story, in which

the game randomly decided which characters are the replicants. Characters

have their own agendas and may turn up in a scene on a randomly determined

course of action and the player can decide to either terminate or join the

replicants. This was supposed to make the game replayable but in reality did

not give sufficient difference to the game to hold sufficient interest for

a second rerun. The player interacted with characters by choosing one of four

conversation modes and then watches a movie sequence. This is no different

from the traditional method of presenting a sensible reply and three silly

responses. The game to reach a larger mass market not only used a film license

but simplified the gameplay.

The Adventure Goes On

The

Action-Adventure sub-genre with its use of 3D graphics and faster more action-orientated

gameplay have become the mainstay on the new consoles. The traditional adventure

games that are flat side-scrolling with cartoon style characters are still

being made but have become marginalized to aficionados of this genre. Adventure

games have the advantage of remaining saleable for a much longer period in

the market place as their appeal is not as technological dependent as other

genres. British developer Revolution started the traditional Broken Sword

adventure series in 1996. Lucas Arts has continued to make games in this

genre and they include Grim Fandango (1998) and Escape from Monkey

Island (2000), which had a 3D look.

The

Action-Adventure sub-genre with its use of 3D graphics and faster more action-orientated

gameplay have become the mainstay on the new consoles. The traditional adventure

games that are flat side-scrolling with cartoon style characters are still

being made but have become marginalized to aficionados of this genre. Adventure

games have the advantage of remaining saleable for a much longer period in

the market place as their appeal is not as technological dependent as other

genres. British developer Revolution started the traditional Broken Sword

adventure series in 1996. Lucas Arts has continued to make games in this

genre and they include Grim Fandango (1998) and Escape from Monkey

Island (2000), which had a 3D look.

Copyright: 1998 and 2004 Mark Gallear