|

|||

|

This sundial is located in Tenango de Doria, a small town of about 2000 inhabitants located in the mountains of the Sierra Madre Oriental in Central Mexico, halfway between Mexico City and the Gulf of Mexico. This is Otomi region, and though Spanish is the language spoken by most of the mestizo people in town, otomi is still widely spoken and understood in the smaller villages and rancherias scattered in the countryside. The winds and rains coming from the ocean stay trapped in the circle of mountains and cannot go through to the high plateau of central Mexico, so this makes for a foggy and misty region for at least 5 or 6 months of the year. So, what's the point of placing a sundial

precisely at this region ?

I was actually asked this question by many of the students of the high school at Tenango de Doria during the opening ceremony of the sundial, and my answer to them was that a sundial does not require any justification because it is its own justification. The reason of being of the sundial is just being. And even if it's cloudy half of the year, it's still sunny the other half. And the fact remains that all sundials are, and this one in particular is, a great didactic open book in which we can read the apparent movements of the sun across the sky hour by hour and day by day and correlate them in a direct and visual way to the abstract notions of rotation and translation that we learn at school in our younger years. More curious souls will start wondering what's the meaning of that eight shaped curve called the equation of time and will perhaps learn of some of the irregularities in the movement of the earth on its own axis and on its yearly path around the sun. When the time comes to make the conversion between local apparent time and standard time they really get a kick. Many of them are surprised to learn that the way in which we tell the time and that we take so much for granted is not more than 120 years old, when the earth was divided somewhat arbitrarily in 24 different time zones and each country took its pick. |

|||

|

|||

|

This sundial is inclined 17° off the vertical, that is 73° instead of 90° that corresponds to true vertical. Thus the sundial is parallel to a vertical sundial in latitude 37° 20' N and receives the rays of the sun all year round. Of course, a sundial tells the solar time, or local apparent time, and in order to get the clock time, or standard time, we have to make a conversion. I will not go into all the explanations of why and how it is done and I will assume that the 2 or 3 people that are ever likely to read this page have a minimum knowledge of the dynamics of the system; if not there's plenty of other places where they can get the information. The

longitude of Tenango is 98° 13' W, so it is 32 minutes off the local time at

meridian 90°, which is the meridian in course for central Mexico, 6 hours

behind Greenwich. Adding that to the changing figure of the equation of time

we obtain the standard time. I don't think that a sundial should bother

itself exclusively or primarily on this conversion; after all, standard time

is only a convention, and there is nothing like the beauty of a sundial

telling the true local time. I am willing to compromise and accept the idea

of putting a graph of the equation of time somewhere in the sundial with a

little explanation; the graph itself is interesting enough and it might

arouse the curiosity of some people who will ask themselves what it is for.

But I abhor the notion of displacing the hour lines of the sundial to

accommodate the difference of longitude, and I'm not very happy either with

the idea of putting the equation of time on each hour line and filling the

sundial with curves that always become so messy. I found a nice neat solution, which may have been used at other times and places, but not very often I should say. I start with a central equation of time at the noon line; this equation of time is my calendar. If you look carefully, there are points all along the curve that signal the first of every month, and there's also the name of the month.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

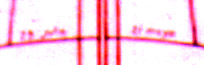

At the other end of each declination line there is a small number that says how many minutes I have to add to the time as told by the sundial (local apparent time) in order to obtain the standard time. This figure includes the difference of longitude and the equation of time, thus it is different every month, as you can see in this magnifications :

|

|||

|

It is actually quite simple, and the kids at the high school don't have much trouble understanding how it is done; it takes them just a bit longer to understand why it is done like that, as this requires a small explanation about such concepts as longitude correction and the equation of time, but those who are interested catch on pretty quickly, and there is always one or two who start asking all kinds of questions, and I love it, because that is exactly what this sundial is all about: to arouse curiosity. Of course there is always a loss of precision when you interpolate both the dates of the year and the hour readings, but what is lost in precision is gained in simplicity. It is just not possible to cram a sundial with too many hour lines and declination lines. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Sundial furniture This sundial is 75 x 105 cms. of dimension. It is hand painted in tiles with special pigments, and then the tile is fired in a kiln at around 750 ° of temperature and the pigments become embedded into the glaze of the tile, becoming impervious to any external agents like rain or sunshine, or even solvents like thinners, turpentine or whatever. They can remain at the exterior and face the elements for very long periods of time with no noticeable deterioration, and in Mexico there are churches and colonial palaces that are covered with painted tiles that have been there for 3 or 4 centuries at least. These pigments can be used with brushes as in oil painting, or with quills, this allows for very fine lines and extremely precise detail. ( This detail, by the way, does not show up in the photographs of this page; all of these photos are enlargements of the main one, and the detail is lost. I have to take close up photographs of the sundial when I go back to Mexico ). So let's start from top to bottom.

Between the sun and the hour lines there is the motto : Como una sombra se va la vida "Life goes by like a shadow" There are hour lines from 7 am to 5 pm. In the summertime the sun rises some half an hour before 6 am and sets also some time around 6:30 pm, but this being a mountainous region and with a couple of structures or small trees towards the horizon lines we can say that the sun never hits the sundial or its shadow is too week to be readable beneath the hour lines included. There are lines for every hour and half hour. There is an equation of time at the central noon line, and this 8 shaped curve also functions as a calendar. There are declination lines for the equinoxes (the central straight line), the summer solstice (the bottom segment of hyperbole) and the winter solstice (the top hyperbole). The shadow of the small hole in the gnomon can never fall outside these two curves, it wanders all year round between those two limits. There are also declination lines for the supposed entrance of the sun into each of the constellations of the zodiac, or at least as they were 2500 years ago; they remain a convention and they are handy for dividing the rest of the year into more or less equally spaced time lapses, that is, every month. At the central part of each declination line there is the date of the year, and at the tip there is the name and the symbol of the Zodiac constellation, and the number of minutes that have to be added to the local time in order to obtain the standard time. |

|||

The bottom part of the

sundial is there just for the pleasure of doing it. First, there is Nahui Ollin. 4-Movement, or the date in which the actual era of the fifth sun is going to end. According to Aztec Mythology, there have been four historical ages, called Suns - those of earth, wind, fire and water. Each has been destroyed by a cosmic cataclysm. The present era is that of the Sun of Movement, Ollintonatiuh. Nahui Ollin is at the center of the Stone of the Sun, also known as the Aztec Calendar, housing the image of Tonatiuh, God of the Sun. For more on Nahui Ollin, see the links section. Then there are two constellation maps, for both the northern and the southern hemispheres. The main constellations are shown, as well as some of the brightest stars and the milky way. These two maps are flanking a representation of the celestial sphere. This one is a nice piece of work. It is a Ptolemaic universe with the earth at the center, and the horizon, celestial equator and tropics, celestial poles and the ecliptic represented. Along the ecliptic we can see the points of the solstices and equinoxes. These three maps are made each in an individual tile, and are about 14 x 14 centimeters; the small detail including the names of stars and constellations can be appreciated up to a distance of about 1 meter.

|

|||

At the far right there is a compass or rose of winds. The sun rises in the east and sets in the west, it seems. |

|||

| And finally, at the bottom

of the sundial we have some general information.

Solar quadrant direct SOUTH with declination lines and equation of time. Local apparent time and conversion to legal time. Inclination of the plate 73° |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The date of creation of the sundial was 1993; it was not put into place until 1999, when I finally went back home and did what I had to do. The sundial is framed by an Aztec motif, which interesting enough is reminiscent of some greek pottery motifs. |

|||

|

At the base of the sundial (not shown in the picture) there is a tile that works as a plaque, and it says :

|

|||

| A little bit of trivia

|

|||

Tenango de Doria is located

at latitude 20° 20' N, thus in the tropics, and if a vertical sundial is

facing direct south it will not receive the sun on its surface for two

months of the year, that is, from May 21st when the sun crosses the zenith

on its way north towards the tropic of cancer, till July 22nd, when the sun

is on its way

south towards the equator and again is directly overhead. If we want

a direct south sundial at this latitude to work all year round, it has to be

tilted, or inclined a number of degrees, thus not perfectly vertical.

Tenango de Doria is located

at latitude 20° 20' N, thus in the tropics, and if a vertical sundial is

facing direct south it will not receive the sun on its surface for two

months of the year, that is, from May 21st when the sun crosses the zenith

on its way north towards the tropic of cancer, till July 22nd, when the sun

is on its way

south towards the equator and again is directly overhead. If we want

a direct south sundial at this latitude to work all year round, it has to be

tilted, or inclined a number of degrees, thus not perfectly vertical.

There's also

the seven common declination lines, that is, the lines for each of the

solstices, the equinoxes and for the supposed entrance of the sun into each

of the signs of the zodiac, which are just conventional dates as we know.

There is the date of the year at each line of declination as well.

There's also

the seven common declination lines, that is, the lines for each of the

solstices, the equinoxes and for the supposed entrance of the sun into each

of the signs of the zodiac, which are just conventional dates as we know.

There is the date of the year at each line of declination as well.

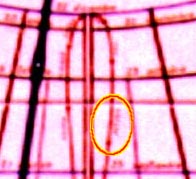

The small hole near the tip

of the gnomon is the marker of the calendar; wherever its shadow falls on

the sundial plate is the date of the year. It is accurate to 1 millimeter.

As you can see in this picture the shadow falls somewhere near the

declination line for the 19th of February ("Pisces") - 23rd October ("Scorpius"),

so the actual date may be either the 29th of October or the 12th of

February. Depending on which date it is, we have to follow the line of

declination to see how many minutes we have to add to our reading; if it is

February, it must be a number between 44 and 47, and closer to the latter,

let's say 46 minutes. If it is October, it must be a number between 17 and

19, and closer to the former, so it is almost 18 minutes.

The small hole near the tip

of the gnomon is the marker of the calendar; wherever its shadow falls on

the sundial plate is the date of the year. It is accurate to 1 millimeter.

As you can see in this picture the shadow falls somewhere near the

declination line for the 19th of February ("Pisces") - 23rd October ("Scorpius"),

so the actual date may be either the 29th of October or the 12th of

February. Depending on which date it is, we have to follow the line of

declination to see how many minutes we have to add to our reading; if it is

February, it must be a number between 44 and 47, and closer to the latter,

let's say 46 minutes. If it is October, it must be a number between 17 and

19, and closer to the former, so it is almost 18 minutes. At

the base of the gnomon there is an aztec glyph of the sun, and surrounding

the glyph there is a powerful flaming sun. The gnomon itself is made of

brass and has a small hole in a notch towards its tip. The shadow of this

hole is the marker of the calendar.

At

the base of the gnomon there is an aztec glyph of the sun, and surrounding

the glyph there is a powerful flaming sun. The gnomon itself is made of

brass and has a small hole in a notch towards its tip. The shadow of this

hole is the marker of the calendar.

First

there is a description of the sundial. It says :

First

there is a description of the sundial. It says : Then

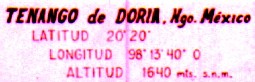

there are the coordinates of Tenango de Doria, Hidalgo, Mexico, including

the latitude, longitude and altitude.

Then

there are the coordinates of Tenango de Doria, Hidalgo, Mexico, including

the latitude, longitude and altitude. And

finally there is the signature, Tlamanalli, which means offering, and its

kanji in japanese.

And

finally there is the signature, Tlamanalli, which means offering, and its

kanji in japanese.