Atlas Page 76

By Henry T. Burgess

A ROCKY headland, lashed by angry surges; bold and jagged cliffs a hundred feet high, storm-worn into a thousand fantastic forms, and trending northward as far as the eye could reach; at their feet dangerous reefs stretching far out into the sea fringing the coast-line with a boiling surf; behind them a level and uninteresting looking country, relieved only by two symmetrical cones of no great elevation, but verdant to their summits —such was the scene beheld by Lieutenant Grant, of the "Lady Nelson," on December 3rd, 1800, and it was the first glimpse by European eyes of any part of the coast now allotted to South Australia. He had left England nearly eight months before, and profiting by the discoveries of Surgeon Bass and Captain Flinders, was about to make the passage between Tasmania and the mainland which no outward-bound vessel had ever attempted. Accordingly he found himself in entirely unknown seas, traversing a route along which, so far as records tell, no sail had ever previously glimmered. Though the well-marked features of Mounts Gambier and Schank render it unquestionable that it was Cape Northumberland he sighted, this glimpse of the extreme southern point of the colony was so limited and brief that it is not unfair to assign the honour of discovering South Australia to Captain Flinders, who had supplied the information that directed the course of the "Lady, Nelson," and who himself not long afterwards appeared on the scene.

Reference has been made in a previous part of this work to the important services rendered by that intrepid navigator in connection with the exploration of the Australian coast, but it is necessary to describe his course along this portion of the continent a little more in detail. Leaving King George’s Sound early in 1802, he soon passed the farthest point reached by the early Dutch explorers, coasted the Great Australian Bight, entered every-bay and delineated every headland till, turning northward, he found his way into the spacious and landlocked harbour of Port Lincoln, with the beauty of which he was exceedingly charmed. Still voyaging north, he thoroughly, examined the western shore of Spencer’s Gulf. When its waters became too shallow even for the little "Investigator," he pushed his boat up the narrow and winding inlet at its head as far as it would go, and thence conducted a small party to the summit of the highest mountain that was in sight, which gave him a view of the great depression wherein Lake Torrens lies, and convinced him that no river from the interior fell into the gulf. Returning southward, along the eastern coast, he passed through the straits that still bear the name of his vessel, searched St. Vincent’s Gulf with equal care, taking special note of the bold Mount Lofty range in the distance, and then bore away eastward through Backstairs Passage, between Cape Jervis and Kangaroo Island.

France had entered the lists against England in the work of discovery, but was too late in the field for the accomplishment of her purpose. The competing expeditions met in friendly encounter at the wide and curving bay that still by its name preserves the memory of that episode. There was then only a comparatively short distance between Encounter Bay and Cape Northumberland, whence the chain of English discovery was again unbroken all the way to Port Jackson. With characteristic chivalry and good taste, Captain Flinders allowed the French nomenclature to remain in the region where the French discoverers had precedence. Hence we have Lacepede, Guichen, and Rivoli Bays, Capes Bernouilli and Buffon, and other titles of Commander Baudin’s affixing. Happily, South Australia has escaped being called Terre Napoleon.

In several of the names given by Captain Flinders to

the localities he visited, he has left behind him a reminder of the perils he so

courageously dared. Anxious Bay, Memory Cove, Mount Misery, Avoid Bay, and Cape

Catastrophe are all very suggestive of dangers feared or passed. The name of one of his

midshipmen, who subsequently became a still more famous leader, is preserved in Franklin

Harbour —an inlet on the west coast of Spencer’s Gulf; his own can never be

forgotten, and South Australians have called their largest electoral district and most

important range of mountains after him. On Monument Hill, overlooking the pleasantly

situated town of Port Lincoln and the placid waters of Boston Bay, stands a plain obelisk

erected to his memory under the personal superintendence of Lady Franklin, in compliance

with the wishes of her illustrious husband. It bears the following inscription:

—"The place from which the Gulf and its shores were first surveyed on 20th Feb.,

1802, by Matthew Flinders, R.N., commanding H.M.S. ‘Investigator,’ the

discoverer, of the country, now called South Australia, was set apart on 12th Jan., 1841,

with the sanction of Lieut. -Col. Gawler, K.H., the governor of the colony, and in the

first year of the government of Captain Grey, adorned with this monument to the perpetual

memory of the illustrious navigator, his honoured commander, by John Franklin, R.N.,

K.C.H., K.R., Lieutenant- Governor of Van Diemen’s Land." The comprehensiveness

of this record is noteworthy; it enumerates a complete series of historical facts, and

associates four names that are all ell worthy of being kept in remembrance.

In several of the names given by Captain Flinders to

the localities he visited, he has left behind him a reminder of the perils he so

courageously dared. Anxious Bay, Memory Cove, Mount Misery, Avoid Bay, and Cape

Catastrophe are all very suggestive of dangers feared or passed. The name of one of his

midshipmen, who subsequently became a still more famous leader, is preserved in Franklin

Harbour —an inlet on the west coast of Spencer’s Gulf; his own can never be

forgotten, and South Australians have called their largest electoral district and most

important range of mountains after him. On Monument Hill, overlooking the pleasantly

situated town of Port Lincoln and the placid waters of Boston Bay, stands a plain obelisk

erected to his memory under the personal superintendence of Lady Franklin, in compliance

with the wishes of her illustrious husband. It bears the following inscription:

—"The place from which the Gulf and its shores were first surveyed on 20th Feb.,

1802, by Matthew Flinders, R.N., commanding H.M.S. ‘Investigator,’ the

discoverer, of the country, now called South Australia, was set apart on 12th Jan., 1841,

with the sanction of Lieut. -Col. Gawler, K.H., the governor of the colony, and in the

first year of the government of Captain Grey, adorned with this monument to the perpetual

memory of the illustrious navigator, his honoured commander, by John Franklin, R.N.,

K.C.H., K.R., Lieutenant- Governor of Van Diemen’s Land." The comprehensiveness

of this record is noteworthy; it enumerates a complete series of historical facts, and

associates four names that are all ell worthy of being kept in remembrance.

Commander Baudin pursued his course westward, visiting Kangaroo Island, both of the gulfs, and the mainland, but the only tangible token now remaining of his presence in that part of South Australia is an inscription on a massive slaty boulder that stands a few feet above high-water mark on the shore a little to the east of Hog Bay, Kangaroo Island. It is believed that he landed there for the purpose of replenishing his water-casks, and the interesting object is locally known as the Frenchman’s Rock.

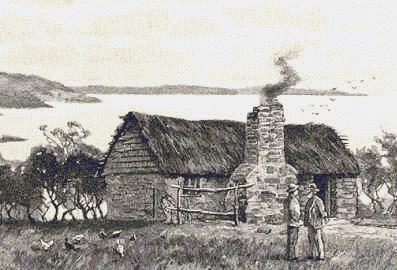

For many years Kangaroo Island was more frequently

visited than the mainland. Whalers and sealers resorted there occasionally, and the

earliest white settlers in South Australia were deserters from those vessels. The first of

all was Thomas Whalley, who absconded from the "General Gates" in 1816, and

landed close to the site of the present telegraph station. In 1824 George Bates landed at

Dashwood’s Bay. He still lives at Hog Bay in what is believed to be the first stone

dwelling ever erected in the province. Though eighty-seven years of age, he enjoys

comparatively robust health, but is chiefly supported by rations from the government. His

claim to be "the oldest inhabitant" is undisputed.

For many years Kangaroo Island was more frequently

visited than the mainland. Whalers and sealers resorted there occasionally, and the

earliest white settlers in South Australia were deserters from those vessels. The first of

all was Thomas Whalley, who absconded from the "General Gates" in 1816, and

landed close to the site of the present telegraph station. In 1824 George Bates landed at

Dashwood’s Bay. He still lives at Hog Bay in what is believed to be the first stone

dwelling ever erected in the province. Though eighty-seven years of age, he enjoys

comparatively robust health, but is chiefly supported by rations from the government. His

claim to be "the oldest inhabitant" is undisputed.

Sixty years ago the great geographical problem of New South Wales was the outlet of the

large rivers that were seen flowing to the westward. Their general course suggested ideas,

of a large inland sea.  Late in 1829 Captain

Sturt undertook to set the question at rest by following them down, and while doing so he

suddenly emerged from the snags and fallen timber that almost blocked the Murrumbidgee

into a magnificent river which he named the Murray. Down that noble stream he floated week

after week till, crossing the wide expanse of Lake Alexandrina, he found his course

arrested by the breakers of the Southern Ocean rolling over the bar at the river’s

mouth. He had solved the problem, but his position was one of extreme peril. The blacks

were treacherous and hostile; his crew was weakened by toil and privations; provisions

were growing scarce, and he had been drawn to an alarming distance from his base of

operations. He did not dare either to linger or to explore the country to any great

extent. After escaping innumerable perils, and enduring the monotonous strain of a

wearisome pull of nearly two thousand miles against the current, he and his party reached

Sydney in safety, and this splendid enterprise not only dispelled the myth of an inland

ocean but attracted greater attention to southern Australia.

Late in 1829 Captain

Sturt undertook to set the question at rest by following them down, and while doing so he

suddenly emerged from the snags and fallen timber that almost blocked the Murrumbidgee

into a magnificent river which he named the Murray. Down that noble stream he floated week

after week till, crossing the wide expanse of Lake Alexandrina, he found his course

arrested by the breakers of the Southern Ocean rolling over the bar at the river’s

mouth. He had solved the problem, but his position was one of extreme peril. The blacks

were treacherous and hostile; his crew was weakened by toil and privations; provisions

were growing scarce, and he had been drawn to an alarming distance from his base of

operations. He did not dare either to linger or to explore the country to any great

extent. After escaping innumerable perils, and enduring the monotonous strain of a

wearisome pull of nearly two thousand miles against the current, he and his party reached

Sydney in safety, and this splendid enterprise not only dispelled the myth of an inland

ocean but attracted greater attention to southern Australia.

Captain

Sturt spoke in glowing terms of the picturesque ranges he had seen, and the fertile plains

between them and the river. To follow up his discoveries an expedition was despatched in

the following year, under Captain Barker of the object being to 39th Regiment and Mr.

Kent, especial ascertain whether any communication existed between the Murray and the Gulf

of St. Vincent. Ascending the winding Onkaparinga in their boat what is now known as

Noarlunga, they thence penetrated the bush to the summit of Mount Lofty, and from that

commanding eminence feasted their eyes on the splendid panorama that lay beneath and

around, and which for extent and interest has few to equal it in the colonies. To the east

rose a mountain, previously mistaken by Captain Sturt for Mount Lofty, which has since

been appropriately named Mount Barker. After returning to their vessel, the explorers

proceeded up the gulf, more closely examined the plains —with the promise of which

they wore highly gratified —found and named the little river Sturt after the

discoverer of the Murray, and then went round to Encounter Bay on their homeward journey.

Captain

Sturt spoke in glowing terms of the picturesque ranges he had seen, and the fertile plains

between them and the river. To follow up his discoveries an expedition was despatched in

the following year, under Captain Barker of the object being to 39th Regiment and Mr.

Kent, especial ascertain whether any communication existed between the Murray and the Gulf

of St. Vincent. Ascending the winding Onkaparinga in their boat what is now known as

Noarlunga, they thence penetrated the bush to the summit of Mount Lofty, and from that

commanding eminence feasted their eyes on the splendid panorama that lay beneath and

around, and which for extent and interest has few to equal it in the colonies. To the east

rose a mountain, previously mistaken by Captain Sturt for Mount Lofty, which has since

been appropriately named Mount Barker. After returning to their vessel, the explorers

proceeded up the gulf, more closely examined the plains —with the promise of which

they wore highly gratified —found and named the little river Sturt after the

discoverer of the Murray, and then went round to Encounter Bay on their homeward journey.

This expedition materially influenced future settlement by, the excellent report of the country which it gave, but it had a tragic termination. Still following up the work of his predecessor, Captain Barker swain the Murray near its mouth to obtain a view of the country beyond, and to take some -bearings, for which purpose he carried his compass on his head. His companions watched him climb the sand hummock afterwards known as Barker’s Knoll, and then he disappeared from their sight for ever. It was subsequently stated that the blacks, startled by the strange and to them unnatural whiteness of his skin, speared him and threw his body into the breakers. There seems to have been no motive whatever for the act but the mere impulse to kill, which in savage natures seems irresistible.

Many cases of equally unprovoked attack are found among the early records of

exploration and settlement. The aboriginal tribes were at constant feud with each other,

and manifested great hatred to strangers. They had ample store of weapons that at short

distances were sufficiently effective, were usually ready enough to fight at the shortest

notice, and were prompt -to resent the intrusion of strangers into their territory. Their

general condition was extremely low.  They lived wandering

lives, making temporary shelter of a few branches of trees covered with skins or mats

whenever they chose to encamp, and obtained most of their food supplies by hunting and

fishing. Though the Europeans have taken possession of the land they roamed over but did

not occupy, it cannot be said that their claims have been ignored or their interests

neglected. In addition to land reserves, and other means adopted for their welfare, the

institutions at Point Macleay on Lake Alexandrina, Point Pearce on Spencer’s Gulf,

Poonindie near Port Lincoln, and at Lake Hope in the far interior, have been well

sustained by public and private beneficence. In these the natives have been taught the

rudiments of education and the truths of Christianity. They have been trained to use the

plough, the reaper, and the winnowing machine, and to manage cattle and sheep. Only

partial success, however, has attended these kindly and patient efforts to elevate them in

the scale of humanity. A few of them have become skilful shearers and fairly successful

farmers, but the breath of civilisation seems to wither the race, and it is doomed to

total extinction.

They lived wandering

lives, making temporary shelter of a few branches of trees covered with skins or mats

whenever they chose to encamp, and obtained most of their food supplies by hunting and

fishing. Though the Europeans have taken possession of the land they roamed over but did

not occupy, it cannot be said that their claims have been ignored or their interests

neglected. In addition to land reserves, and other means adopted for their welfare, the

institutions at Point Macleay on Lake Alexandrina, Point Pearce on Spencer’s Gulf,

Poonindie near Port Lincoln, and at Lake Hope in the far interior, have been well

sustained by public and private beneficence. In these the natives have been taught the

rudiments of education and the truths of Christianity. They have been trained to use the

plough, the reaper, and the winnowing machine, and to manage cattle and sheep. Only

partial success, however, has attended these kindly and patient efforts to elevate them in

the scale of humanity. A few of them have become skilful shearers and fairly successful

farmers, but the breath of civilisation seems to wither the race, and it is doomed to

total extinction.

During the period referred to, other brief visits were paid to Port Lincoln, Yorke’s Peninsula, and the gulfs, in one of which a Captain Jones discovered the inlet that is now known as the Port river, and has become the chief harbour of the colony. By these means a degree of general knowledge of the capabilities of the country was acquired, and the way prepared for its permanent occupation.

click here to return to main page