SOUTH AUSTRALIA - HISTORICAL

SKETCH 5 ...

Atlas Page 80

By Henry T. Burgess

PROGRESS AND DEVELOPMENT

CAPTAIN GREY.

RESUMING our history, we return to the regime introduced by Governor Grey of which

uncompromising retrenchment was the marked feature. It intensified the severity of the

crisis for which the action of the Home Commissioners was partly responsible. Things grew

worse and worse. Captain Grey was an autocrat, and ruled despotically. Not content with

pursuing the methods adopted by his predecessor for getting the people out into the

country, he seemed to be determined to make the city as unattractive as possible. A

municipal council had been elected before the new governor arrived, but it interfered with

his independent action, and he could not work with it. Its members ventured to criticise

his proceedings, and he promptly resented what he considered to be their presumption. When

his relations with the council grew more strained, he questioned the legality of its acts,

disregarded its suggestions, and finally the corporation, which it is believed was the

first ever established in the British colonies, became defunct.

As the governor wielded what was

practically supreme power, he was able to induce the Executive to pass a number of

taxation Acts for the purpose of increasing the revenue. The enlarged indebtedness of the

colony was alleged to be proof that such measures were absolutely necessary, but augmented

taxation is always unwelcome, and by the people it was on that occasion strenuously

opposed. It was declared that Captain Grey’s policy was having the effect of still

further deepening the commercial depression. At a public meeting of the citizens, it was

denounced in unmeasured terms, and the City Council remonstrated against it; but the only

effect of this resistance was to make him angry. He had formed his plans deliberately, and

was absolutely inflexible in carrying them out. He was accused of cherishing the definite

purpose of keeping the colony in complete subjection, but charges of that kind brought

about no difference in his method of action. It can easily be seen that during the earlier

part of his administration the state of affairs was not at all agreeable. As time wore on,

however, and prospects improved, a better tone prevailed. Much of the irritation subsided,

and if the governor did not become actually popular, his unpopularity very sensibly

diminished. There was, indeed, a marked approach to cordiality of feeling on the part of

the people before the time came for his departure, and within a recent period he

personally assured the writer of his strong attachment to the colony, his sustained

interest in its welfare, and his deep desire to re-visit it and witness the progress it

has made.

As the governor wielded what was

practically supreme power, he was able to induce the Executive to pass a number of

taxation Acts for the purpose of increasing the revenue. The enlarged indebtedness of the

colony was alleged to be proof that such measures were absolutely necessary, but augmented

taxation is always unwelcome, and by the people it was on that occasion strenuously

opposed. It was declared that Captain Grey’s policy was having the effect of still

further deepening the commercial depression. At a public meeting of the citizens, it was

denounced in unmeasured terms, and the City Council remonstrated against it; but the only

effect of this resistance was to make him angry. He had formed his plans deliberately, and

was absolutely inflexible in carrying them out. He was accused of cherishing the definite

purpose of keeping the colony in complete subjection, but charges of that kind brought

about no difference in his method of action. It can easily be seen that during the earlier

part of his administration the state of affairs was not at all agreeable. As time wore on,

however, and prospects improved, a better tone prevailed. Much of the irritation subsided,

and if the governor did not become actually popular, his unpopularity very sensibly

diminished. There was, indeed, a marked approach to cordiality of feeling on the part of

the people before the time came for his departure, and within a recent period he

personally assured the writer of his strong attachment to the colony, his sustained

interest in its welfare, and his deep desire to re-visit it and witness the progress it

has made.

Historians differ very widely in their estimate of the character and effects of Captain

Grey’s administration. On the one hand, it is contended that he saved the colony from

ruin; that it was plunging, or being plunged, recklessly into difficulties from which it

never could have emerged when he took the reins, arrested its downward course, and rescued

it from destruction. On the other hand, he has been described as both harsh and

tyrannical. It is said that he produced a crisis which need not have occurred, caused

disasters that might have been averted, and aggravated evils he might have remedied. His

policy of insisting on the occupation of the land and promoting useful industries is

credited to his predecessor, and the returning prosperity of which he witnessed the

commencement, to causes outside the range of his influence.

Perhaps the truth lies between these extremes. He was, and is, a man of singular

capacity, firmness, and courage; and this is proved by his career in Australia, South

Africa, and New Zealand. He was sent out to do rough and unpleasant work, and it was not

possible for him to do it well and yet please everybody. He is at least entitled to great

credit for his energy and fidelity to what he believed to be his duty. He had to encounter

a storm of popular clamour, which would have caused most men to swerve from their course,

but he met it unmoved. For this he is entitled to respect, and if some of his acts seemed

arbitrary at the time, the peculiar difficulties of his position go far towards their

justification.

During this term the colony passed through

its darkest hour, but even before its close a brighter day had dawned. Pastoral products

were increasing, and agriculture was spreading very rapidly, but the prices of all staple

commodities were ruinously low. Sheep were boiled down for their tallow, and wheat was

worth only half-a-crown a bushel, when the mineral wealth of the country was discovered,

and proved its salvation. On January 23rd, 1844, five drayloads of copper ore from the

Kapunda mine reached Adelaide, and caused the wildest excitement. The following year a

shepherd named Pickett came across an outcrop of similar ore fifty, miles farther north.

This was the famous Burra Burra mine, in which the only capital invested was twelve

thousand three hundred and twenty pounds, and from which copper to the value of nearly

five million sterling was taken before it ceased to be worked in 1877. These and other

discoveries greatly revived business, attracted population, remunerated labour, expanded

commerce, and inaugurated permanent prosperity.

During this term the colony passed through

its darkest hour, but even before its close a brighter day had dawned. Pastoral products

were increasing, and agriculture was spreading very rapidly, but the prices of all staple

commodities were ruinously low. Sheep were boiled down for their tallow, and wheat was

worth only half-a-crown a bushel, when the mineral wealth of the country was discovered,

and proved its salvation. On January 23rd, 1844, five drayloads of copper ore from the

Kapunda mine reached Adelaide, and caused the wildest excitement. The following year a

shepherd named Pickett came across an outcrop of similar ore fifty, miles farther north.

This was the famous Burra Burra mine, in which the only capital invested was twelve

thousand three hundred and twenty pounds, and from which copper to the value of nearly

five million sterling was taken before it ceased to be worked in 1877. These and other

discoveries greatly revived business, attracted population, remunerated labour, expanded

commerce, and inaugurated permanent prosperity.

COLONEL ROBE.

ON October 25th, 1845, a change in the administration was effected by a new governor

being privately sworn in. This was Lieut. -Col. Fred. Holt Robe, who had been somewhat

suddenly sent from Mauritius to take the place of Captain Grey, as on account of the

trouble in connection with the Maori war, the Imperial Government was anxious to employ

the proved ability of the latter in New Zealand. It was whispered that Governor Grey had

bequeathed his policy to his successor, and the surmise was strengthened by the apparent

inability or disinclination of Colonel Rob to frame one of his own. The circumstance that

he was only sworn in as lieutenant-governor was also commented upon as indicating that it

was intended for him to occupy merely a temporary and subordinate position, the latter

element applying to the colony over which he was sent to govern as well.

For the most part, Governor Robe was content to follow the example set before him, and

to carry, on the administration according to the lines that had been laid down, but it is

curious that when he diverged from it he generally made a mistake. There are some

half-dozen matters with which his name is especially connected, and it is remarkable that

what he did was subsequently reversed, while what he refused to do was afterwards carried

into effect. Thus he imposed an impolitic royalty, which was soon abolished, on minerals;

he devoted public money to the support of religion in the face of strong opposition. This

stirred up a large amount of strife, and the subsidies were speedily discontinued. He

granted to Bishop Short, as a site for a cathedral, an acre of land in Victoria Square, in

the very centre of the city, close to where the General Post Office now stands; but the

validity of the grant was successfully contested by the City Council on behalf of the

citizens, the Supreme Court deciding, that the Executive had no power to alienate any part

of the public estate. On the other hand, he refused to re-establish the Corporation, and

even declined to sanction the expenditure for repairing the roadway in Hindley Street,

though in the middle of it bullock drays were daily bogged in the mud. The one speech he

made that is distinctly remembered was delivered to a deputation that had been appointed

by a public meeting to wait upon him with a protest against State aid to religion. Holding

his gloves and walking-stick in his hands, he allowed the spokesman to read the document

they had been instructed to present, and then replied —"I have no remarks to

make, gentlemen." Probably he had no intention whatever of being discourteous, but

the incident was remarkably characteristic of his entire administration.

Though this may appear to be an unflattering portraiture, it has to be borne in

mind that Governor Robe was in an anomalous position, for which he was not altogether

responsible. He has been described as an emergency man, and the term is not very

inappropriate. He was by inclination and training, as well as by profession, a thorough

soldier, and had neither a knowledge of the duties which he was unexpectedly called upon

to discharge nor a liking for them. His military career had invested him with a certain

amount of formal preciseness which his confirmed bachelorhood had not tended to decrease.

For all that, he was essentially a high-bred English gentleman, and though he lacked the

flexibility and adaptiveness which tends to popularise a public man, those who came to

know him well, learned to hold him in high esteem, in spite of his habitual reticence and

reserve. He was not to blame because his administration cannot be called a brilliant

success, though it must be admitted that the prosperity of the colony during his term of

office merely shows that its upward movement had become steady and continuous.

Though this may appear to be an unflattering portraiture, it has to be borne in

mind that Governor Robe was in an anomalous position, for which he was not altogether

responsible. He has been described as an emergency man, and the term is not very

inappropriate. He was by inclination and training, as well as by profession, a thorough

soldier, and had neither a knowledge of the duties which he was unexpectedly called upon

to discharge nor a liking for them. His military career had invested him with a certain

amount of formal preciseness which his confirmed bachelorhood had not tended to decrease.

For all that, he was essentially a high-bred English gentleman, and though he lacked the

flexibility and adaptiveness which tends to popularise a public man, those who came to

know him well, learned to hold him in high esteem, in spite of his habitual reticence and

reserve. He was not to blame because his administration cannot be called a brilliant

success, though it must be admitted that the prosperity of the colony during his term of

office merely shows that its upward movement had become steady and continuous.

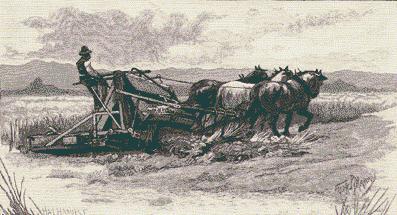

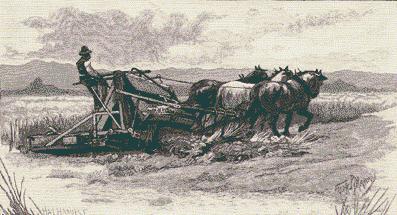

Unquestionably, the most important event of the time was the revolution that took place

in agricultural pursuits by means of the invention of the reaping-machine. On the Adelaide

plains the wheat-straw during harvest-time becomes as brittle as glass, and the grain

perfectly loose in the ear and even were there sufficient labour available for

hand-reaping to be employed, which has never been the case, that method would be wasteful.

As the cultivated area widened, the difficulty increased. Magnificent crops of wheat could

be grown, but the means for their ingathering were too scanty. Rewards were offered for

mechanical contrivances to meet the case. A locomotive thrashing machine, to deal with the

cars alone and leave the straw for subsequent treatment, was the desideratumm and

local inventiveness at length supplied the want. It is said that the first idea came from

an old volume in which was a wood-cut representing a sort of hand-cart used by the ancient

Romans, propelled by one man while another struck the wheat-ears into it. Mr. J. W. Bull

claimed to have evolved in his own mind the idea of a projecting comb with revolving

beaters, operated by a band from the traction-wheel, and to have had the earliest working

model constructed from his suggestions. Others have asserted their share in the invention,

but it is generally conceded that Mr. John Ridley built the first machine that was

actually used. It was a clumsy affair, drawn by a team of bullocks, attached to a pole

that stuck out behind like a tail. This was tested during the harvest of 1843. Other

machines on better principles were made the following year, but another season or two

elapsed before the defects which caused them to break down incessantly were remedied, and

the Ridley reaper came into general use. Since then improvements by scores have been

introduced, and such machines multiplied by the ten thousand. In its way, this invention

has been as important as the discovery of copper, for it has rendered possible the

profitable cultivation of hundreds of thousands of acres, and added incalculably to the

national wealth.

GOVERNOR YOUNG.

THE advent of a civilian governor for the first time was welcomed and regarded

hopefully, by almost all classes, and the sequel showed that as usual the popular instinct

was right. During six eventful years —from August, 1848, to December, 1854 —Sir

H. Ed. Fox Young administered the affairs of the province with marked success, and

witnessed substantial progress in several directions. Some degree of friction between a

governor exercising arbitrary power and a people desiring and competent for representative

institutions was inevitable, and the only wonder is that there was so little, especially

as more or less agitation for constitutional reform was going on all the time. The

governor was careful not to act in a high-handed manner, entered heartily into schemes

that promised to develop the resources of the country, sympathised with it in all its

affairs, and laboured energetically, if not always judiciously, in the promotion of its

interests.

A severe though only temporary check was experienced in 1851 and for some time

afterwards, when the attractions of the goldfields in Victoria almost denuded the colony

of its labouring population. Merchants, bankers, and all owners of property were driven

almost to their wit’s end. Mines were closed, enterprise arrested, and business

brought to a standstill. At this juncture, when everything portended a speedy collapse,

Mr. Gregory S. Walters, of the English and South Australian Copper Company, suggested to

Mr. —afterwards Sir —Richard D. Hanson, who was then attorney-general, the

adoption of a measure to make gold by weight a legal tender at a fixed standard value. The

idea was eagerly embraced, and its adoption was especially urged by Mr. Tinline, the

manager of the Bank of South Australia, who saw in it a way of escape from the serious

embarrassment that loomed near through the growing depreciation of all kinds of

securities. His share in the work has been frequently and fully recognised, but that of

Mr. Walters has passed comparatively unnoticed. The principle was incorporated in the

Bullion Act, for the passing of which by the Legislature all standing orders were

suspended. To give it effect, the overland escort was organised, and was skilfully managed

and led by Mr. Alexander Tolmer, a portion of the wealth acquired by the South Australian

gold-diggers thus being brought into the colony, and exercising a beneficial effect which

was speedily witnessed in a renewal of confidence and activity. Next in importance must be

placed as an historical event the opening of the Murray to steam navigation. Captain

Cadell, having descended the river from Victoria in a canvas boat, drew fresh attention to

the capabilities of that stream and the prospects of profitable traffic along its course.

His Excellency took an enthusiastic interest in the subject. Numerous accidents had

occurred at the mouth of the river, in one of which Sir J. Jeffcott was drowned, and it

was generally accepted that the shifting channel and treacherous bar rendered that passage

impracticable, but the governor believed that a good port might be made of Port Elliot if

connected by a short tramway of seven miles with the Murray at Goolwa. He got a bonus

offered for the first steamer of a certain power that should reach the Darling junction,

and he accompanied Captain Cadell to Echuca, one thousand three hundred miles, in the

"Lady Augusta." There can be no doubt that he was too sanguine. He seemed to

ignore all the difficulties attending the navigation of a river with such a variable water

supply as the Murray, and the possibility of the eastern colonies drawing off its trade at

points farther inland. He got the tramway constructed, and twenty thousand pounds spent on

a breakwater at Port Elliot.  He believed and wrote that it

would become "the New Orleans of the Australian Mississippi," but the money was

literally thrown into the sea The place is a mere jagged notch in a rocky coast, a life

trap, utterly inadequate for a harbour, and has never been of any use for such a purpose.

The glowing prospects have faded, the river traffic is under a heavy cloud, and Victoria

taps it with her railway system.

He believed and wrote that it

would become "the New Orleans of the Australian Mississippi," but the money was

literally thrown into the sea The place is a mere jagged notch in a rocky coast, a life

trap, utterly inadequate for a harbour, and has never been of any use for such a purpose.

The glowing prospects have faded, the river traffic is under a heavy cloud, and Victoria

taps it with her railway system.

Other public works were initiated, and notably railways to the Port and northward.

Governor Young saw the commencement but not the completion of the former. The inexperience

of almost everybody concerned in its construction cost the colony an enormous sum. The

work was accomplished after such a fashion that a single line of less than eight miles

over a dead level, without a single engineering difficulty to overcome, and only one

bridge to build, cost nearly, a quarter of a million sterling. The wonder that such a

prodigality of expenditure must excite may be mitigated somewhat if it be the fact that

what Charles Simeon Hare, one of its many superintendents, complained of were true,

namely, that being required to find work for the unemployed, in order to relieve the

labour market which was suffering from ail unwonted plethora, he had to set fourteen men

to fill a cart!

CONSTITUTIONAL

GOVERNMENT.

THIS period was one of great political activity. There had been a legislative council,

consisting of four official and four non-official members, but the people had nothing to

do with their appointment, and the govern or -preside tit, armed with veto power, was a

little king. In 1851 a new council assembled, composed of eight nominee and sixteen

elective members. Two years afterwards that body passed ail Act for a parliament to

consist of a legislative council, the members of which were to be appointed by, the

governor, and for life, and a house of assembly elected by the people. The measure was

sent to England for approval, but being, strongly, petitioned against, was referred back

to the colony. A general election to ascertain the feeling of the country, took place in

1855, and the council then chosen formulated the Constitution, which, being assented to by

the Queen, came speedily into operation, and with comparatively slight modifications, has

continued ever since. "Thus was launched," to quote Mr. Anthony Forster,

"in a colony with a population of little over one hundred thousand souls, and placed

sixteen thousand miles away from any controlling authority, a system of responsible

government involving the principles of universal suffrage, vote by ballot, equal electoral

districts, and triennial parliaments. And to a community thus governed was committed the

absolute administration and disposal of the whole territory of the Crown, embracing nearly

three hundred million acres of land. The concession of so vast a power, to be exercised in

untried circumstances, indicated on the part of the Home authorities a large amount of

confidence in the loyalty, intelligence, and prudence of the inhabitants of so distant a

dependency. Nor can it be said, so far as experience goes, that this confidence has been

unwisely or undeservedly bestowed." While this movement was going on, measures for

local government were also being brought into operation. The Corporation of the City of

Adelaide was resuscitated, and district councils were established all over the colony

giving ratepayers in each locality the control and management, to a large extent, of their

local affairs.

GOVERNOR MacDONNELL.

AN interregnum of several months occurred after Sir H. E. F. Young left South Australia

for Tasmania, during which the government was administered by the Hon. Boyle T. Finniss.

Sir Richard Graves MacDonnell took the reins of office In June, 1855, and held them for

the unusual term of nearly seven years. Under his auspices the work of constitutional

reform was completed, and though for a while he seemed to think it his business to give

advice to his ministers, instead of to receive it from them, he soon accepted a more

correct view of the situation. He was energetic, large-minded, and personally popular. His

catholic sympathies induced him to receive the Rev. Thomas Binney as a guest at Government

House, and to request permission for him to preach in an episcopalian church. This Bishop

Short felt it his duty to refuse, and a memorable correspondence followed. The Port

railway was opened, and a beginning made with northern railways by the construction of a

line to Kapunda, fifty miles in length. A few months after the governor, Mr. C. Todd

arrived with telegraphic appliances, and began the energetic course he has since followed.

The first work he superintended was a line from Adelaide to the Port, and it is recalled,

with some amusement, that the revenue therefrom was for the first day five shillings and

six pence; for the second, two shillings and six pence; for the third, one shilling and

nine pence; and for the fourth, one shilling and three pence. A rival line, erected by Mr.

James Macgeorge, had been opened a few weeks before, and took most of the business, but

the government purchased it for eighty pounds, and pulled it down. The next extension was

to Gawler, and in less than three years communication was opened with Melbourne.

The parliament proved its legislative capacity in many ways, but chiefly by passing the

measure, known as the Torrens Act, for simplifying the transfer of land, and for securing

titles to it. Mr. R. R. Torrens, who subsequently received the well-merited honour of

knighthood in recognition of his valuable services, had held the office of collector of

customs, and his experience in the transfer of shipping property, together with the legal

knowledge and experience of land legislation on the continent of Europe possessed by Dr.

Hübbe, who rendered him considerable assistance, enabled him to fight an uphill battle

with complete success.  South Australians are not a little proud of their leading

position in this department of legal reform, and proud also that the example they set has

been copied extensively elsewhere.

South Australians are not a little proud of their leading

position in this department of legal reform, and proud also that the example they set has

been copied extensively elsewhere.

While this was going on, preparation was being made for the opening of the northern

areas for agricultural settlement. An extension of territory was gained by the acquisition

of a strip of country known as No Man’s Land, containing about eighty, thousand

square miles, between the former boundary of the colony, and that of Western Australia,

but it has never been of much real advantage. Mining industry, received an extraordinary

impetus by the discovery of rich deposits of copper on Yorke’s Peninsula. Many mines

were opened, but the most famous and valuable were those at Wallaroo and Moonta. The

latter, without calling up any capital whatever from its shareholders, has paid a million

sterling in dividends.

cont...

click here to return to main page

As the governor wielded what was

practically supreme power, he was able to induce the Executive to pass a number of

taxation Acts for the purpose of increasing the revenue. The enlarged indebtedness of the

colony was alleged to be proof that such measures were absolutely necessary, but augmented

taxation is always unwelcome, and by the people it was on that occasion strenuously

opposed. It was declared that Captain Grey’s policy was having the effect of still

further deepening the commercial depression. At a public meeting of the citizens, it was

denounced in unmeasured terms, and the City Council remonstrated against it; but the only

effect of this resistance was to make him angry. He had formed his plans deliberately, and

was absolutely inflexible in carrying them out. He was accused of cherishing the definite

purpose of keeping the colony in complete subjection, but charges of that kind brought

about no difference in his method of action. It can easily be seen that during the earlier

part of his administration the state of affairs was not at all agreeable. As time wore on,

however, and prospects improved, a better tone prevailed. Much of the irritation subsided,

and if the governor did not become actually popular, his unpopularity very sensibly

diminished. There was, indeed, a marked approach to cordiality of feeling on the part of

the people before the time came for his departure, and within a recent period he

personally assured the writer of his strong attachment to the colony, his sustained

interest in its welfare, and his deep desire to re-visit it and witness the progress it

has made.

As the governor wielded what was

practically supreme power, he was able to induce the Executive to pass a number of

taxation Acts for the purpose of increasing the revenue. The enlarged indebtedness of the

colony was alleged to be proof that such measures were absolutely necessary, but augmented

taxation is always unwelcome, and by the people it was on that occasion strenuously

opposed. It was declared that Captain Grey’s policy was having the effect of still

further deepening the commercial depression. At a public meeting of the citizens, it was

denounced in unmeasured terms, and the City Council remonstrated against it; but the only

effect of this resistance was to make him angry. He had formed his plans deliberately, and

was absolutely inflexible in carrying them out. He was accused of cherishing the definite

purpose of keeping the colony in complete subjection, but charges of that kind brought

about no difference in his method of action. It can easily be seen that during the earlier

part of his administration the state of affairs was not at all agreeable. As time wore on,

however, and prospects improved, a better tone prevailed. Much of the irritation subsided,

and if the governor did not become actually popular, his unpopularity very sensibly

diminished. There was, indeed, a marked approach to cordiality of feeling on the part of

the people before the time came for his departure, and within a recent period he

personally assured the writer of his strong attachment to the colony, his sustained

interest in its welfare, and his deep desire to re-visit it and witness the progress it

has made. During this term the colony passed through

its darkest hour, but even before its close a brighter day had dawned. Pastoral products

were increasing, and agriculture was spreading very rapidly, but the prices of all staple

commodities were ruinously low. Sheep were boiled down for their tallow, and wheat was

worth only half-a-crown a bushel, when the mineral wealth of the country was discovered,

and proved its salvation. On January 23rd, 1844, five drayloads of copper ore from the

Kapunda mine reached Adelaide, and caused the wildest excitement. The following year a

shepherd named Pickett came across an outcrop of similar ore fifty, miles farther north.

This was the famous Burra Burra mine, in which the only capital invested was twelve

thousand three hundred and twenty pounds, and from which copper to the value of nearly

five million sterling was taken before it ceased to be worked in 1877. These and other

discoveries greatly revived business, attracted population, remunerated labour, expanded

commerce, and inaugurated permanent prosperity.

During this term the colony passed through

its darkest hour, but even before its close a brighter day had dawned. Pastoral products

were increasing, and agriculture was spreading very rapidly, but the prices of all staple

commodities were ruinously low. Sheep were boiled down for their tallow, and wheat was

worth only half-a-crown a bushel, when the mineral wealth of the country was discovered,

and proved its salvation. On January 23rd, 1844, five drayloads of copper ore from the

Kapunda mine reached Adelaide, and caused the wildest excitement. The following year a

shepherd named Pickett came across an outcrop of similar ore fifty, miles farther north.

This was the famous Burra Burra mine, in which the only capital invested was twelve

thousand three hundred and twenty pounds, and from which copper to the value of nearly

five million sterling was taken before it ceased to be worked in 1877. These and other

discoveries greatly revived business, attracted population, remunerated labour, expanded

commerce, and inaugurated permanent prosperity. Though this may appear to be an unflattering portraiture, it has to be borne in

mind that Governor Robe was in an anomalous position, for which he was not altogether

responsible. He has been described as an emergency man, and the term is not very

inappropriate. He was by inclination and training, as well as by profession, a thorough

soldier, and had neither a knowledge of the duties which he was unexpectedly called upon

to discharge nor a liking for them. His military career had invested him with a certain

amount of formal preciseness which his confirmed bachelorhood had not tended to decrease.

For all that, he was essentially a high-bred English gentleman, and though he lacked the

flexibility and adaptiveness which tends to popularise a public man, those who came to

know him well, learned to hold him in high esteem, in spite of his habitual reticence and

reserve. He was not to blame because his administration cannot be called a brilliant

success, though it must be admitted that the prosperity of the colony during his term of

office merely shows that its upward movement had become steady and continuous.

Though this may appear to be an unflattering portraiture, it has to be borne in

mind that Governor Robe was in an anomalous position, for which he was not altogether

responsible. He has been described as an emergency man, and the term is not very

inappropriate. He was by inclination and training, as well as by profession, a thorough

soldier, and had neither a knowledge of the duties which he was unexpectedly called upon

to discharge nor a liking for them. His military career had invested him with a certain

amount of formal preciseness which his confirmed bachelorhood had not tended to decrease.

For all that, he was essentially a high-bred English gentleman, and though he lacked the

flexibility and adaptiveness which tends to popularise a public man, those who came to

know him well, learned to hold him in high esteem, in spite of his habitual reticence and

reserve. He was not to blame because his administration cannot be called a brilliant

success, though it must be admitted that the prosperity of the colony during his term of

office merely shows that its upward movement had become steady and continuous. He believed and wrote that it

would become "the New Orleans of the Australian Mississippi," but the money was

literally thrown into the sea The place is a mere jagged notch in a rocky coast, a life

trap, utterly inadequate for a harbour, and has never been of any use for such a purpose.

The glowing prospects have faded, the river traffic is under a heavy cloud, and Victoria

taps it with her railway system.

He believed and wrote that it

would become "the New Orleans of the Australian Mississippi," but the money was

literally thrown into the sea The place is a mere jagged notch in a rocky coast, a life

trap, utterly inadequate for a harbour, and has never been of any use for such a purpose.

The glowing prospects have faded, the river traffic is under a heavy cloud, and Victoria

taps it with her railway system. South Australians are not a little proud of their leading

position in this department of legal reform, and proud also that the example they set has

been copied extensively elsewhere.

South Australians are not a little proud of their leading

position in this department of legal reform, and proud also that the example they set has

been copied extensively elsewhere.