SOUTH AUSTRALIA - TOPOGRAPHICAL DESCIPTION 6 ...

Atlas Page 88

By Henry T. Burgess

| The Western System |

Hamley Bridge to Quorn |

THE WESTERN SYSTEM.

BENDING a little to the west after leaving Roseworthy, the main line turns the flank of

the hilly country, and skirts a succession of plains for about fourteen miles. To the west

there is a wide landscape of cultivated sections alternating with patches of un-reclaimed

scrub. The river Light, which has cut for itself a deep channel between rugged hills, is

crossed by a latticed iron bridge, in two spans of about a hundred and fifty feet each,

and seventy feet above the water level. When constructed it was considered a fine piece of

engineering work, and named after Colonel Hamley, the then acting governor of the

province. A mile or so beyond, the Gilbert falls into the Light, and on the peninsula

between these streams lies the station and township that derives its name from the Hamley

Bridge. It is a smart, active-looking little place, with good hotels, stores, banks, and

churches. It is the junction between the main north line and a hundred and fifty miles of

railway constructed on the narrow or three feet six inches gauge, which constitutes what

is called the western system. The break of gauge is one of the difficulties of South

Australian railway management, and the advantage gained by economy of construction has

been purchased at, the expense of much delay and inconvenience. Similar difficulties have

been met in cases of other and intercolonial connections, and the advisability of adopting

a uniform gauge has long been apparent.

It is a slow and monotonous journey of twenty-two miles from Hamley Bridge to

Balaclava, where a junction is effected with the line that runs inland for about

forty-three miles from Port Wakefield to Blyth, at about sixteen miles from the Port.

These railways traverse a part of the great plain that stretches perhaps a hundred miles

northward from Adelaide, and from the shores of Gulf St. Vincent to the outlying spurs and

foothills of the central range that divides it from the valley of the Murray. Its greatest

breadth from east to west is about thirty miles, and the topography is very uniform. It is

almost all fit for cultivation, but there are limestone rises and low sandhills especially

near the coast, where the soil is poorer than the average, but at no point is it more than

two or three hundred feet above the sea-level. There are vast prairies without a single

tree, a good deal of country that is lightly timbered and park-like, and hundreds on

hundreds of square miles densely covered with mallee scrub. Years ago this was considered

comparatively worthless, as it yielded no grass for pasturage, and the expense of grubbing

the tough mallee roots rendered farming unprofitable. Necessity, however, is the mother of

invention. An Irishman named Mullens is said to have set the example of dispensing with

the toll of clearing. He chopped down the scrub near the roots, burnt it, dragged heavy

harrows about among the stumps, sowed the scratched surface, and the season being a good

one, reaped a first-rate crop. The process became known as "Mullenising," and

implements were made to carry it on. The most important of these is the stump-jumping

plough, which is claimed to have been the invention of a farmer named Charles Branson,

from whose drawings the first stump-jumper was made by Mr. J. W. Scott, of Alma. Several

machinists have adopted and improved upon the original idea, which has worked almost as

great a revolution in farming as the Ridley reaper. The modern implement ha a strong iron

frame, carrying three plough-shares attached to heavily-weighted levers. When they strike

a stump, root, rock, or other obstruction, they simply climb over it, instead of bringing

tie team up with a violent jerk. One ploughman can easily do the work of three, besides

dispensing with the aid of a driver. Within five years of this invention being made known,

more than half a million acres of scrub-lands that were formerly considered unsuitable for

agriculture were taken up by farmers, and its fame has spread far and wide.

It is a slow and monotonous journey of twenty-two miles from Hamley Bridge to

Balaclava, where a junction is effected with the line that runs inland for about

forty-three miles from Port Wakefield to Blyth, at about sixteen miles from the Port.

These railways traverse a part of the great plain that stretches perhaps a hundred miles

northward from Adelaide, and from the shores of Gulf St. Vincent to the outlying spurs and

foothills of the central range that divides it from the valley of the Murray. Its greatest

breadth from east to west is about thirty miles, and the topography is very uniform. It is

almost all fit for cultivation, but there are limestone rises and low sandhills especially

near the coast, where the soil is poorer than the average, but at no point is it more than

two or three hundred feet above the sea-level. There are vast prairies without a single

tree, a good deal of country that is lightly timbered and park-like, and hundreds on

hundreds of square miles densely covered with mallee scrub. Years ago this was considered

comparatively worthless, as it yielded no grass for pasturage, and the expense of grubbing

the tough mallee roots rendered farming unprofitable. Necessity, however, is the mother of

invention. An Irishman named Mullens is said to have set the example of dispensing with

the toll of clearing. He chopped down the scrub near the roots, burnt it, dragged heavy

harrows about among the stumps, sowed the scratched surface, and the season being a good

one, reaped a first-rate crop. The process became known as "Mullenising," and

implements were made to carry it on. The most important of these is the stump-jumping

plough, which is claimed to have been the invention of a farmer named Charles Branson,

from whose drawings the first stump-jumper was made by Mr. J. W. Scott, of Alma. Several

machinists have adopted and improved upon the original idea, which has worked almost as

great a revolution in farming as the Ridley reaper. The modern implement ha a strong iron

frame, carrying three plough-shares attached to heavily-weighted levers. When they strike

a stump, root, rock, or other obstruction, they simply climb over it, instead of bringing

tie team up with a violent jerk. One ploughman can easily do the work of three, besides

dispensing with the aid of a driver. Within five years of this invention being made known,

more than half a million acres of scrub-lands that were formerly considered unsuitable for

agriculture were taken up by farmers, and its fame has spread far and wide.

All over these plains are scattered settlements every few miles. The farmers’

holdings are large, and consequently the population is scanty, but the entire region is

well supplied with such adjuncts of civilisation as schools, churches, and assembly rooms.

Every little township has its post-office, machinist’s shop, public-house, and store,

and in the larger there are banks, telegraph stations, and other public buildings. The

yield of wheat depends mainly on the rainfall, but with only a few pence per acre to pay

for rent, and such appliances as the stump-jumper and stripper, an average of a very few

bushels, at moderate prices, will pay expenses and perhaps ‘leave a margin of profit.

Balaclava is a straggling, un-picturesque town of about six hundred inhabitants on the

river Wakefield, which, except in the time of winter torrents, is only a slender stream.

After harvest it is lively but, except as a place of business, has few attractions.

Hoyleton, twelve miles along the railway line inland, and Blyth, eight miles further, at

its terminus, are small townships supported by the large agricultural districts

surrounding them. Port Wakefield, at the mouth of the river sixteen miles to the west,

being near the head of Gulf St. Vincent, is the natural outlet for the produce of an

immense area, but owing to the shallowness of the water only vessels of light draught can

come up to the town, and those that do are left high and dry by the ebb tide. Yet in the

busy season the public and private wharfs, though the former is five hundred yards long,

are crowded with trucks and stacks of wheat. It has a large number of fine buildings of

the usual character, and a population at least equal to that of Balaclava.

Across

the head of the gulf, and running a long distance north and south, is seen the Hummocks

Range, to surmount which the railway makes a complete zig-zag. As it climbs the slope the

view, looking southward on a clear day, is exceedingly, beautiful. The foreground is open,

well grassed, and park-like to the water’s edge. Beyond is the deep blue of the gulf,

which as it widens away to the right is only bounded by the horizon. On the farther shore

the white buildings of Port Wakefield seem to shine in the sunlight, contrasting strongly

with the mangroves that line the beach. Behind it, and to the north, are the extensive

plains that have been traversed. Ranges of hills form the background, and perhaps Mount

Lofty is dimly’ visible, though, as the crow flies, it is seventy miles away. From

the crest of the range there are easy descending gradients along a course nearly due west,

across grassy plains, through stretches of scrub, and past cultivated clearings, till

Kadina is reached, a hundred and seventeen miles from Adelaide.

Across

the head of the gulf, and running a long distance north and south, is seen the Hummocks

Range, to surmount which the railway makes a complete zig-zag. As it climbs the slope the

view, looking southward on a clear day, is exceedingly, beautiful. The foreground is open,

well grassed, and park-like to the water’s edge. Beyond is the deep blue of the gulf,

which as it widens away to the right is only bounded by the horizon. On the farther shore

the white buildings of Port Wakefield seem to shine in the sunlight, contrasting strongly

with the mangroves that line the beach. Behind it, and to the north, are the extensive

plains that have been traversed. Ranges of hills form the background, and perhaps Mount

Lofty is dimly’ visible, though, as the crow flies, it is seventy miles away. From

the crest of the range there are easy descending gradients along a course nearly due west,

across grassy plains, through stretches of scrub, and past cultivated clearings, till

Kadina is reached, a hundred and seventeen miles from Adelaide.

The surface formation of this part of Yorke’s Peninsula is limestone with a thin

coating of soil, and the effect on a stranger is almost distressing. Timber there is none,

nor is there a hill to relieve the monotony. Except where there are some bushes and

stunted scrub, everything glares and glistens in the sunlight. The streets, roads,

sidewalks, and buildings are of an almost uniform whiteness. It may be said that they look

bright, clean, and cheerful, but they almost blind the eyes when the sun is unclouded. A

few gardens show the change that can and will be wrought before long, by irrigation, but

at present water is too scarce and precious to be used for that purpose.  The

town is well laid out with what will be a handsome square in the centre, and contains a

large number of very fine buildings that were erected when the mines were in full swing

and everything prosperous. Since their decadence, the prosecution of farming in the

surrounding district has done something to sustain business. Besides the railway from Port

Wakefield, there is another running thirty-three miles in a north westerly direction to

Snowtown, the centre of a large district, but despite these aids the revival of

copper-mining is the hope of the place. A mile away to the south, across the railway line,

a number of tall engine houses and a maze of winding-gear connected with the several

shafts denote the position of the Wallaroo, Kurilla, and other mines. The deposits of

copper were first brought to light by the burrowing operations of an inoffensive wombat.

He was summarily ejected, his hole enlarged, and Wombat shaft has become world-renowned.

Seven miles west from Kadina is Wallaroo Bay, a deep indentation in the coast of

Spencer’s Gulf forming an excellent harbour. It has ample wharfage accommodation and

a jetty sixteen hundred feet long, at which vessels of two thousand tons’ burden may

lie and load or unload in any weather, but the town itself is not much to boast of. A

cluster of chimneys and a perpetual cloud of smoke show the position of the smelting

works, which have thirty-six furnaces. A mountain containing tens of thousands of tons of

coal, on one side, and a still larger mountain of slag on the other, suggest the magnitude

of the work that is carried on. A tram-line running southward for eleven miles, mostly

through thick scrub, but with occasional glimpses of the sea, conducts to Moonta. Emerging

from the scrub the famous mines, with their tall engine-houses, slender winding-gear, and

mountainous heaps of refuse, are seen to the left. The town lies on a slope about a mile

nearer the sea, which renders its closely packed and stately buildings peculiarly

conspicuous. The most prominent of all is the Wesleyan Church, which both for

commodiousness and architectural style is worthy of a metropolis. As at Kadina, the

business places and public buildings were mostly erected when times were flush, and are on

an ambitious scale. Moonta is the commercial centre, for, though thousands of people live

on the mine property, there are no places of business allowed. The population fluctuates

with the prosperity of the mines, but at one time, before the depreciation in the price of

copper, Kadina, Wallaroo, and Moonta, with the neighbouring townships, had upwards of

twenty thousand inhabitants. The Moonta mine, without calling up any capital from its

shareholders, even for its early development, has paid in dividends more than a million

pounds sterling. Here and there amid the surrounding scrub engine-houses and other tokens

of mining ventures that are now abandoned may, be met with, but the payable cupriferous

area seems to be singularly limited. Southern Yorke’s Peninsula has few striking

features. Throughout its entire length of more than a hundred miles it is occupied by,

either squatters or farmers, and some parts are very productive. It has neither mountains

nor rivers, but in the south are number of salt lakes —glittering sheets of purest

white like roughened ice —sometimes several miles in circumference. Much of it is

lightly timbered with gum-trees or shea-oaks, but there are also open plains and patches

of dense scrub. The principal towns are Maitland, Minlaton, and Yorketown, and the bulk of

the produce usually finds its way from one or other of several small shipping places to

Port Adelaide.

The

town is well laid out with what will be a handsome square in the centre, and contains a

large number of very fine buildings that were erected when the mines were in full swing

and everything prosperous. Since their decadence, the prosecution of farming in the

surrounding district has done something to sustain business. Besides the railway from Port

Wakefield, there is another running thirty-three miles in a north westerly direction to

Snowtown, the centre of a large district, but despite these aids the revival of

copper-mining is the hope of the place. A mile away to the south, across the railway line,

a number of tall engine houses and a maze of winding-gear connected with the several

shafts denote the position of the Wallaroo, Kurilla, and other mines. The deposits of

copper were first brought to light by the burrowing operations of an inoffensive wombat.

He was summarily ejected, his hole enlarged, and Wombat shaft has become world-renowned.

Seven miles west from Kadina is Wallaroo Bay, a deep indentation in the coast of

Spencer’s Gulf forming an excellent harbour. It has ample wharfage accommodation and

a jetty sixteen hundred feet long, at which vessels of two thousand tons’ burden may

lie and load or unload in any weather, but the town itself is not much to boast of. A

cluster of chimneys and a perpetual cloud of smoke show the position of the smelting

works, which have thirty-six furnaces. A mountain containing tens of thousands of tons of

coal, on one side, and a still larger mountain of slag on the other, suggest the magnitude

of the work that is carried on. A tram-line running southward for eleven miles, mostly

through thick scrub, but with occasional glimpses of the sea, conducts to Moonta. Emerging

from the scrub the famous mines, with their tall engine-houses, slender winding-gear, and

mountainous heaps of refuse, are seen to the left. The town lies on a slope about a mile

nearer the sea, which renders its closely packed and stately buildings peculiarly

conspicuous. The most prominent of all is the Wesleyan Church, which both for

commodiousness and architectural style is worthy of a metropolis. As at Kadina, the

business places and public buildings were mostly erected when times were flush, and are on

an ambitious scale. Moonta is the commercial centre, for, though thousands of people live

on the mine property, there are no places of business allowed. The population fluctuates

with the prosperity of the mines, but at one time, before the depreciation in the price of

copper, Kadina, Wallaroo, and Moonta, with the neighbouring townships, had upwards of

twenty thousand inhabitants. The Moonta mine, without calling up any capital from its

shareholders, even for its early development, has paid in dividends more than a million

pounds sterling. Here and there amid the surrounding scrub engine-houses and other tokens

of mining ventures that are now abandoned may, be met with, but the payable cupriferous

area seems to be singularly limited. Southern Yorke’s Peninsula has few striking

features. Throughout its entire length of more than a hundred miles it is occupied by,

either squatters or farmers, and some parts are very productive. It has neither mountains

nor rivers, but in the south are number of salt lakes —glittering sheets of purest

white like roughened ice —sometimes several miles in circumference. Much of it is

lightly timbered with gum-trees or shea-oaks, but there are also open plains and patches

of dense scrub. The principal towns are Maitland, Minlaton, and Yorketown, and the bulk of

the produce usually finds its way from one or other of several small shipping places to

Port Adelaide.

HAMLEY BRIDGE TO QUORN.

THE route lies up the valley of the Gilbert, which, after a few

miles, opens into a fertile plain gently sloping east and west from the river to the

ranges. It is three to four miles wide and perhaps twelve miles long, bare of timber, but

nearly every acre has been under the plough. Near Riverton the country is more broken, and

a forest of gum-trees is passed through just before reaching the town. Riverton is

sixty-two miles from Adelaide, and a bright, busy place of about six hundred inhabitants,

sheltered from the north and west by tree clothed hills, itself embowered in gardens and

plantations, and the centre of a prosperous region. Almost the same description will apply

to Saddleworth, five miles farther on, except that it is not so large and has more

picturesque surroundings. Manoora and Mintaro, which are the next succeeding stations, are

much smaller, but the whole of this run of twenty miles is exceedingly pretty. It has

nothing of the grand or romantic, but there is a succession of gently-swelling hills and

fertile vales, clad with verdure, adorned with trees, and every here and there a

substantial farm-house with its roomy outbuildings, smiling gardens, and prolific orchard.

It is beautiful in spring-time, when the tender green of the young wheat contrasts with

the chocolate-coloured fallows; and perhaps still more so, when for miles together even

the fences are concealed by the standing corn that has turned golden under the summer sun,

and the hum of the reaper is heard in the land. The line has gradually ascended till at

Mintaro it is thirteen hundred and sixty-nine feet above the sea level. Here the timber is

left behind, the soil becomes less fertile, and another plain is opened twenty miles or

more in length, flanked by bare-looking hills that recede to the right ‘and left.

They are more abrupt in their outlines, running up to narrower ridges and sharper peaks,

introducing an element of picturesqueness and conveying a suggestion of mineral wealth. At

Farrell’s Flat, eighty-seven miles from town, extent rather than variety is the chief

feature of the landscape. The vision ranges over a shallow valley bounded in the distance

by serrated hills, and containing at least two hundred square miles suitable for either

agriculture or pasturage, most of which is occupied by sheep-runs.

THE route lies up the valley of the Gilbert, which, after a few

miles, opens into a fertile plain gently sloping east and west from the river to the

ranges. It is three to four miles wide and perhaps twelve miles long, bare of timber, but

nearly every acre has been under the plough. Near Riverton the country is more broken, and

a forest of gum-trees is passed through just before reaching the town. Riverton is

sixty-two miles from Adelaide, and a bright, busy place of about six hundred inhabitants,

sheltered from the north and west by tree clothed hills, itself embowered in gardens and

plantations, and the centre of a prosperous region. Almost the same description will apply

to Saddleworth, five miles farther on, except that it is not so large and has more

picturesque surroundings. Manoora and Mintaro, which are the next succeeding stations, are

much smaller, but the whole of this run of twenty miles is exceedingly pretty. It has

nothing of the grand or romantic, but there is a succession of gently-swelling hills and

fertile vales, clad with verdure, adorned with trees, and every here and there a

substantial farm-house with its roomy outbuildings, smiling gardens, and prolific orchard.

It is beautiful in spring-time, when the tender green of the young wheat contrasts with

the chocolate-coloured fallows; and perhaps still more so, when for miles together even

the fences are concealed by the standing corn that has turned golden under the summer sun,

and the hum of the reaper is heard in the land. The line has gradually ascended till at

Mintaro it is thirteen hundred and sixty-nine feet above the sea level. Here the timber is

left behind, the soil becomes less fertile, and another plain is opened twenty miles or

more in length, flanked by bare-looking hills that recede to the right ‘and left.

They are more abrupt in their outlines, running up to narrower ridges and sharper peaks,

introducing an element of picturesqueness and conveying a suggestion of mineral wealth. At

Farrell’s Flat, eighty-seven miles from town, extent rather than variety is the chief

feature of the landscape. The vision ranges over a shallow valley bounded in the distance

by serrated hills, and containing at least two hundred square miles suitable for either

agriculture or pasturage, most of which is occupied by sheep-runs.

The more attractive belt that has been crossed extends for many miles both east and

west of the railway line. From Saddleworth a good road runs eastward through a gap in the

ranges, and it is a delightful drive for twenty miles and more, past Marrabel and

Frederickswalde, across the Anlaby run to Eudunda. Turning west, the coach to Clare may be

taken, but a better way is to make the starting-point from Riverton, and go through the

pretty village of Rhynie, past Undalya, picturesquely situated on the banks of the

Wakefield, to Auburn —"Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plain." It

well merits the description, though it is not a deserted village by any means. It occupies

part of a fertile plain among the hills, surrounded by farms, and is eminently lovely. It

has three banks, half a dozen churches, a large town hall, well-furnished institute, good

hotels, and the usual complement of public buildings.

Villages and towns occur at shorter intervals along this road than anywhere

else in the north. Four miles from Auburn comes Leasingham, three miles further is

Watervale, and Penwortham and Seven Hills are only two miles apart. The scenery throughout

is charming. Willows fringe the watercourses, in some places patriarchal gum-trees are

left standing, the slopes are fertile cornfields, and the flats luxuriant meadows.

Cottages half-hidden by climbing roses and other creepers,’ blooming gardens and

vineyards and orchards in full bearing, are frequent for miles on either hand. The towns,

though small, are thriving, and the number of substantial stone buildings, public as well

as private, is a healthy indication. Over the hills, about two miles to the east of Seven

Hills, is a large Roman Catholic college, and near by is an exceedingly neat and

well-finished church. The property includes a large vineyard, with spacious wine-vaults,

and the produce is celebrated throughout the neighbourhood. Still further in the same

direction is the town of Mintaro, on the slope of the range, and close to it are large

slate quarries, whence flags of excellent quality are exported to all parts of Australia.

Villages and towns occur at shorter intervals along this road than anywhere

else in the north. Four miles from Auburn comes Leasingham, three miles further is

Watervale, and Penwortham and Seven Hills are only two miles apart. The scenery throughout

is charming. Willows fringe the watercourses, in some places patriarchal gum-trees are

left standing, the slopes are fertile cornfields, and the flats luxuriant meadows.

Cottages half-hidden by climbing roses and other creepers,’ blooming gardens and

vineyards and orchards in full bearing, are frequent for miles on either hand. The towns,

though small, are thriving, and the number of substantial stone buildings, public as well

as private, is a healthy indication. Over the hills, about two miles to the east of Seven

Hills, is a large Roman Catholic college, and near by is an exceedingly neat and

well-finished church. The property includes a large vineyard, with spacious wine-vaults,

and the produce is celebrated throughout the neighbourhood. Still further in the same

direction is the town of Mintaro, on the slope of the range, and close to it are large

slate quarries, whence flags of excellent quality are exported to all parts of Australia.

Four miles from Seven Hills and eighty-seven from Adelaide is Clare, by far the largest

and most important town of the district. It lies along a pleasant valley sheltered by tree

clothed hills, and from every point of view is charming. The population numbers about

twelve hundred; there are three large agricultural implement manufactories, a tannery,

mill, and fruit preserving establishment. In addition to the usual government offices, it

has a casualty hospital, public baths, churches, five hotels, a large town hall, and a

grammar school. Many of these buildings are of an unusually high order of architecture,

and there are a good many and some private residences. In the neighbourhood are several

large sheep and cattle stations; and some of the estates have mansions that are large,

elegant, and complete, and stand as evidences of the success of their owners’

efforts.

Clare is a focus whence roads radiate through the Broughton, Gulnare, and other

agricultural areas. Fertile plains, divided by low ridges running nearly north and south,

succeed one another till it seems as if there were no end to them. The landscape stretches

before the observer in picturesque undulations of hill and dale, over which in the season

the autumn wind stirs the yellow corn into billowy waves.

Diverging routes lead to Anama, Rochester, Koolunga, Red Hill, Yacka, Narridy,

Georgetown, Spalding, and other townships. Connection with the railway line may be made by

the coach, which, passing the Hill River estate, famous for its prize cattle and sheep

that are of superlative excellence, in a couple of hours rejoins the railway line at

Farrell’s Flat.

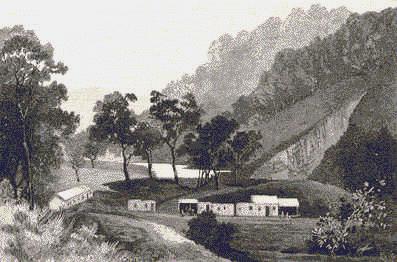

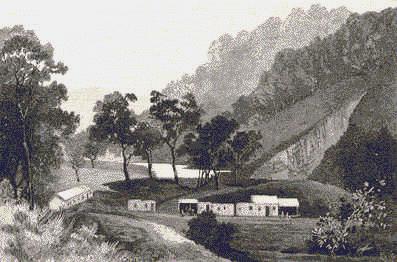

Thirteen miles farther north and a hundred from Adelaide, Burra is reached. Close to

the station is the old Bon Accord mine, in which twenty thousand pounds were sunk

unprofitably, while within "coo-ee distance" copper was being obtained in

abundance. Five minutes’ walk to the brow of the hill, on which a reservoir has been

constructed, brings the visitor into full view of one of the most interesting spots in

South Australia. Its area is surprisingly limited, for it is merely a triangular hollow,

less than a hundred acres in extent, with an outfall towards the Burra Burra Creek. The

topography is peculiar. A horizontal crest runs nearly north and south, and there are

flanking hills of rather lower elevation which thus enclose a sort of pocket, out of which

nearly a quarter of a million tons of copper ore has been taken, having a total estimated

value of four million seven hundred and forty-nine thousand two hundred and twenty-four

pounds, and there are known to be rich deposits still untouched. Right across the hollow

there now stretches a gaping, jagged chasm, with precipitous sides a hundred to two

hundred feet in depth. At the bottom there lies a greenish pool, said to be thirty feet

deep and intensely cold, as well it may be. On its margin stand a couple of jigging

hutches, and perhaps a miner or two may be seen at work, but there are no other signs of

activity.  Several

engine-houses are still standing, with their valuable machinery carefully protected, and

others are dismantled. They look as if they might stand for ever, some of their walls are

six feet thick, of solid masonry built with massive stones measuring as much as seven feet

by three. Huge water-wheels connected with batteries of stampers, long lengths of

"launders" that are dropping to pieces, immense capstans with eighteen-inch

cables coiled round them, and sturdy trees growing between their arms, lofty shears still

bearing, as a vane the orthodox figure of a miner with pick and gad, jigging machines and

purifiers that need renovating themselves, old water reservoirs, in which brushwood is

growing, rusty beams of pumping-engines, iron piping and parts of machinery that has been

taken to pieces lying in confused heaps, tottering poppet-heads and dilapidated sheds and

workshops, all combine to produce a melancholy impression. The yawning gulf and the

mountains of refuse that have come out of it tell of former industry. Once this little

hollow was as full of life as an anthill, for more than eleven hundred men and boys found

employment in it; but now all is silence, desolation, and decay.

Several

engine-houses are still standing, with their valuable machinery carefully protected, and

others are dismantled. They look as if they might stand for ever, some of their walls are

six feet thick, of solid masonry built with massive stones measuring as much as seven feet

by three. Huge water-wheels connected with batteries of stampers, long lengths of

"launders" that are dropping to pieces, immense capstans with eighteen-inch

cables coiled round them, and sturdy trees growing between their arms, lofty shears still

bearing, as a vane the orthodox figure of a miner with pick and gad, jigging machines and

purifiers that need renovating themselves, old water reservoirs, in which brushwood is

growing, rusty beams of pumping-engines, iron piping and parts of machinery that has been

taken to pieces lying in confused heaps, tottering poppet-heads and dilapidated sheds and

workshops, all combine to produce a melancholy impression. The yawning gulf and the

mountains of refuse that have come out of it tell of former industry. Once this little

hollow was as full of life as an anthill, for more than eleven hundred men and boys found

employment in it; but now all is silence, desolation, and decay.

The town of Burra is in two distinct portions. Near the railway station are Redruth,

Aberdeen, and other contiguous town ships, and divided from them by a clear half mile,

with the vast ruins of the smelting works on one side and the mine on the other, is

Kooringa. The municipality includes them all. Kooringa is the principal business portion.

In it are the largest stores, banks, hospital, institute, six churches, post and telegraph

station, sale yards, machinists’ establishments, brewery, and three hotels. At the

Redruth end are other places of business, churches, and hotels, the court-house, gaol

(sometimes without an occupant), and two flourmills. A public school with accommodation

for eight hundred scholars stand as nearly as possible midway between the extremities. In

the cliff-like banks of the creek, which traverses the town from end to end, hundreds of

dwellings were excavated, but the winter floods destroyed them all. Many years ago it was

filled with stately gum-trees, and the hills that enclose the town on every side were

covered with scrub or dotted with trees, but the vandalism of those days converted into

fuel everything that would burn, and stripped them bare. Hideous barrenness followed, but

an active corporation and an abundant water supply have wrought wonders. Arboriculture has

been prosecuted vigorously, and a marked improvement is visible every year. From a hill

top near at hand apparently boundless plains, that are chiefly occupied by pastoralists,

are seen stretching away to the east, with an horizon like that of the sea. In every other

direction serrated ridges rise, one behind another, as far as the eye can reach. The

observer can hardly help questioning whether it be true that, in some freakish mood,

Nature deposited in one small pocket of the scores within sight among these- hills nearly

five millions worth of copper leaving all the rest empty, and bare.

From Burra to Terowie is a run of forty miles, through farms and sheep-runs, past Mount

Bryan. Hallett, Ulooloo, and Yarcowie. After the first few miles the eastern hills are

bolder in outline and less devoid of timber. There is some degree of picturesqueness in

the Razorback Range, and Mount Bryan lifts its stony crest three thousand feet above the

sea. Between the plains near Hallett and those in which Yarcowie lies, the broken Ulooloo

district is crossed. In the gullies coming out of the ranges are alluvial gold-diggings.

The government geologist describes the country as highly auriferous, but no reefs or veins

have been found. The scarcity of water is a drawback to prospecting, but eighteen thousand

pounds’ worth of the precious metal is known to have been transmitted through the

Hallett post office. Between Yarcowie and Terowie, "Goyder’s line of

rainfall" is crossed, and thence for many miles the railway runs parallel wit that

important boundary, which has been drawn with truth and skill. The difference between the

country to the east and that to the west of it is clearly perceptible. On the one side are

great salt-bush plains and barren hills, where water is extremely scarce; but on the

other, a more copious rainfall and better land. Terowie lies at the edge of one of these

far-stretching eastern plains, and derives benefit from the circumstance that all the

lines farther north are built on the narrow gauge, as the break of gauge necessitates a

large railway establishment. The station-yard is nearly a mile long, usually crowded with

traffic, and there are large workshops for engine repairing, etc. Terowie has about seven

hundred inhabitants, and its favourable position makes it a busy and relatively important

place. Seven miles farther on, the railway attains its greatest altitude, and Gumbowie

station, a hundred and forty-seven miles from Adelaide, is considerably higher than that

at Mount Lofty, being almost two thousand feet above the sea. After winding about among

stony hills, the line comes out on bare and windy uplands, whence the eye ranges over

hundreds of square miles of valley and plain bounded by distant hills. All of it is

occupied, much of it cultivated, and in the massive breadths of the landscape there is

something impressive and even grand. Fourteen miles from Terowie is Petersburg-its

ambitious rival, though, at present, only half the size-which claims to be the capital of

the north, for it is a double junction, as the lines to the Barrier Ranges and to Port

Pirie branch off here to the east and west respectively. Besides having a large farming

district of its own, this circumstance renders it an important centre. It is rather

pleasantly situated, and especially at harvest-time does an enormous business for a town

of its size.

The line to Cockburn has acquired unexpected

importance since it was opened through the marvellous metalliferous discoveries in the

Barrier Ranges. For a considerable distance it passes through hilly country, diversified

by gum-trees, pines, silver wattle, and mallee, among Which there is some good

agricultural land, and then for about a hundred and twenty miles it is nearly all

salt-bush, only fit for sheep-runs, dreary and monotonous. About halfway and some twenty

miles or so to the north of the line are the Teetulpa goldfields. The geological formation

of the ranges that run north and south through the colony stretches out a long and wide

promontory eastward. There are primary and plutonic rocks, and for at least thirty miles

they are proved to be auriferous. Were the richness of the field commensurate with its

extent, there would be here a second Ballarat. Sanguine investors say that such will yet

be the case, and the workings at the Waukaringa and other mines are held to encourage the

belief. The railway is constructed forty miles further —to Silverton and Broken Hill

in New South Wales. Since the earlier parts of this work were published these places have

sprung into importance by the development of the richest silver-mines in the wide world.

The argentiferous area is extensive and fabulously rich. The mines are numerous, but

Broken Hill is the glory of the region. The formation of the hill itself, with its steeply

inclined slopes and rugged crest of black, calcined-looking boulders, is most impressive

to the spectator. A descent into the mine is like a visit to the palace .of a silver king.

The town is growing with phenomenal rapidity, and it is believed that ere long it will

contain a larger population than that of any other outside the capitals of the several

colonies. Northwards, there is a stanniferous belt at least twenty-eight miles long and

three miles wide. There is a slaty formation intersected by granite dykes, of which fifty

or more are proved to be tin bearing. Their value is at present only conjectural. In some

seasons of the year these ranges are very beautiful. The hills are picturesque, and the

ground is covered by a brilliant carpet of wild flowers, among which the gorgeous Sturt

pea is conspicuous, acres together being sheeted by its scarlet and black clusters of

bloom.

The line to Cockburn has acquired unexpected

importance since it was opened through the marvellous metalliferous discoveries in the

Barrier Ranges. For a considerable distance it passes through hilly country, diversified

by gum-trees, pines, silver wattle, and mallee, among Which there is some good

agricultural land, and then for about a hundred and twenty miles it is nearly all

salt-bush, only fit for sheep-runs, dreary and monotonous. About halfway and some twenty

miles or so to the north of the line are the Teetulpa goldfields. The geological formation

of the ranges that run north and south through the colony stretches out a long and wide

promontory eastward. There are primary and plutonic rocks, and for at least thirty miles

they are proved to be auriferous. Were the richness of the field commensurate with its

extent, there would be here a second Ballarat. Sanguine investors say that such will yet

be the case, and the workings at the Waukaringa and other mines are held to encourage the

belief. The railway is constructed forty miles further —to Silverton and Broken Hill

in New South Wales. Since the earlier parts of this work were published these places have

sprung into importance by the development of the richest silver-mines in the wide world.

The argentiferous area is extensive and fabulously rich. The mines are numerous, but

Broken Hill is the glory of the region. The formation of the hill itself, with its steeply

inclined slopes and rugged crest of black, calcined-looking boulders, is most impressive

to the spectator. A descent into the mine is like a visit to the palace .of a silver king.

The town is growing with phenomenal rapidity, and it is believed that ere long it will

contain a larger population than that of any other outside the capitals of the several

colonies. Northwards, there is a stanniferous belt at least twenty-eight miles long and

three miles wide. There is a slaty formation intersected by granite dykes, of which fifty

or more are proved to be tin bearing. Their value is at present only conjectural. In some

seasons of the year these ranges are very beautiful. The hills are picturesque, and the

ground is covered by a brilliant carpet of wild flowers, among which the gorgeous Sturt

pea is conspicuous, acres together being sheeted by its scarlet and black clusters of

bloom.

From Petersburg westward to Port Pirie is a journey of seventy-four miles through rich

agricultural areas. Forest reserves under the control of the government, and other

plantations thrive well on the hillsides, and the plains yield heavy crops of wheat.  The

principal towns on the line are Yongala, Jamestown, Caltowie, Gladstone, Laura (which is

reached by a short branch line from Gladstone), and Crystal Brook. Jamestown, which is the

largest, contains over pine hundred inhabitants. These and other towns in the district

have the same general characteristics. They are admirably laid .out with wide streets and

reserves for recreation -grounds, have numerous substantial and handsome public and

private edifices well built of stone, and are provided with post and telegraph offices,

schools, churches, institutes, assembly halls, machinists’ establishments, mills,

stores, and hotels. Ornamental planting has been freely indulged in. Laura is prettily

situated under the Flinders Range on the Rocky River, which supplies it with an ornamental

sheet of water during part of the year, and as the result of liberal expenditure by the

ratepayers, Jamestown has become perfect gem of a country town.

The

principal towns on the line are Yongala, Jamestown, Caltowie, Gladstone, Laura (which is

reached by a short branch line from Gladstone), and Crystal Brook. Jamestown, which is the

largest, contains over pine hundred inhabitants. These and other towns in the district

have the same general characteristics. They are admirably laid .out with wide streets and

reserves for recreation -grounds, have numerous substantial and handsome public and

private edifices well built of stone, and are provided with post and telegraph offices,

schools, churches, institutes, assembly halls, machinists’ establishments, mills,

stores, and hotels. Ornamental planting has been freely indulged in. Laura is prettily

situated under the Flinders Range on the Rocky River, which supplies it with an ornamental

sheet of water during part of the year, and as the result of liberal expenditure by the

ratepayers, Jamestown has become perfect gem of a country town.

It is a romantic drive from Laura to Port Pirie across the range, and still more

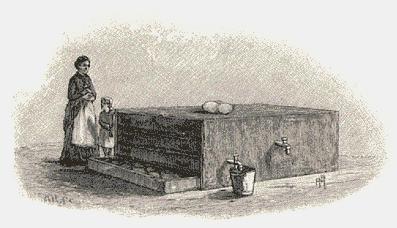

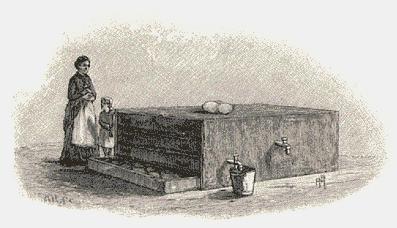

interesting if Beetaloo be taken in the way. Here an immense reservoir worthy of being

called an inland sea is being constructed, from which it is intended to supply the

Yorke’s Peninsula towns ninety miles away, as well as other places on the line of

delivery.

Port Pirie is a larger town than any of those just named, and the

chief port for the northern areas. In a good season its export of wheat will amount in

value to nearly a million sterling. The inlet on which it is situated has been deepened by

dredging so that vessels of fifteen hundred tons burden can come up to the wharf. It is

stragglingly built on a pipe-clay looking flat, and the one redeeming feature in its

scenery is the bold face of the Flinders Range, which somewhat resembles Mount Lofty as

seen from Adelaide, though its rugged and massive outline renders it more striking in

appearance.

Port Pirie is a larger town than any of those just named, and the

chief port for the northern areas. In a good season its export of wheat will amount in

value to nearly a million sterling. The inlet on which it is situated has been deepened by

dredging so that vessels of fifteen hundred tons burden can come up to the wharf. It is

stragglingly built on a pipe-clay looking flat, and the one redeeming feature in its

scenery is the bold face of the Flinders Range, which somewhat resembles Mount Lofty as

seen from Adelaide, though its rugged and massive outline renders it more striking in

appearance.

Resuming the northern route from Petersburg, other agricultural tracts are met with.

All along the eighty miles to Quorn, one plain or valley after another, running nearly

north and south is met with. At Orroroo, the principal intermediate town, there is an

uninterrupted view for twenty miles up the Walloway Plain, and the enclosing ranges

—especially the Oladdie Hills and the towering granite peaks of Black Rock —are

highly picturesque. Up the Pekina Creek, and among the hills to the west, there is much

romantic scenery. Quorn is a large and well-built town two hundred and sixty miles from

Adelaide, at the point where contact is made with the transcontinental railway from Port

Augusta into the far interior. Westward of the railway line there is much fine scenery. A

drive through the rocky gorge between Wirrabara and Port Germein is most impressive. From

the summit of Mount Remarkable, which, though three thousand feet high, is not difficult

of access, the view is wonderful for extent and diversity; and at the foot of the mountain

Melrose nestles among giant gum-trees. Threading the precipitous defile between the

perpendicular cliffs of Horrocks’ Pass —a cleft in the Flinders Range on the

road from Melrose to Port Augusta —there are scenes of almost awful grandeur. All the

way from Adelaide to Quorn, and from the railway to the sea-board, though the population

is sparse because the holdings are large, the rule is to find thriving towns and townships

every few miles, between them prosperous farms or sheep and cattle stations, good roads

everywhere, and generally interesting scenery.

cont...

click here to return to main page

It is a slow and monotonous journey of twenty-two miles from Hamley Bridge to

Balaclava, where a junction is effected with the line that runs inland for about

forty-three miles from Port Wakefield to Blyth, at about sixteen miles from the Port.

These railways traverse a part of the great plain that stretches perhaps a hundred miles

northward from Adelaide, and from the shores of Gulf St. Vincent to the outlying spurs and

foothills of the central range that divides it from the valley of the Murray. Its greatest

breadth from east to west is about thirty miles, and the topography is very uniform. It is

almost all fit for cultivation, but there are limestone rises and low sandhills especially

near the coast, where the soil is poorer than the average, but at no point is it more than

two or three hundred feet above the sea-level. There are vast prairies without a single

tree, a good deal of country that is lightly timbered and park-like, and hundreds on

hundreds of square miles densely covered with mallee scrub. Years ago this was considered

comparatively worthless, as it yielded no grass for pasturage, and the expense of grubbing

the tough mallee roots rendered farming unprofitable. Necessity, however, is the mother of

invention. An Irishman named Mullens is said to have set the example of dispensing with

the toll of clearing. He chopped down the scrub near the roots, burnt it, dragged heavy

harrows about among the stumps, sowed the scratched surface, and the season being a good

one, reaped a first-rate crop. The process became known as "Mullenising," and

implements were made to carry it on. The most important of these is the stump-jumping

plough, which is claimed to have been the invention of a farmer named Charles Branson,

from whose drawings the first stump-jumper was made by Mr. J. W. Scott, of Alma. Several

machinists have adopted and improved upon the original idea, which has worked almost as

great a revolution in farming as the Ridley reaper. The modern implement ha a strong iron

frame, carrying three plough-shares attached to heavily-weighted levers. When they strike

a stump, root, rock, or other obstruction, they simply climb over it, instead of bringing

tie team up with a violent jerk. One ploughman can easily do the work of three, besides

dispensing with the aid of a driver. Within five years of this invention being made known,

more than half a million acres of scrub-lands that were formerly considered unsuitable for

agriculture were taken up by farmers, and its fame has spread far and wide.

It is a slow and monotonous journey of twenty-two miles from Hamley Bridge to

Balaclava, where a junction is effected with the line that runs inland for about

forty-three miles from Port Wakefield to Blyth, at about sixteen miles from the Port.

These railways traverse a part of the great plain that stretches perhaps a hundred miles

northward from Adelaide, and from the shores of Gulf St. Vincent to the outlying spurs and

foothills of the central range that divides it from the valley of the Murray. Its greatest

breadth from east to west is about thirty miles, and the topography is very uniform. It is

almost all fit for cultivation, but there are limestone rises and low sandhills especially

near the coast, where the soil is poorer than the average, but at no point is it more than

two or three hundred feet above the sea-level. There are vast prairies without a single

tree, a good deal of country that is lightly timbered and park-like, and hundreds on

hundreds of square miles densely covered with mallee scrub. Years ago this was considered

comparatively worthless, as it yielded no grass for pasturage, and the expense of grubbing

the tough mallee roots rendered farming unprofitable. Necessity, however, is the mother of

invention. An Irishman named Mullens is said to have set the example of dispensing with

the toll of clearing. He chopped down the scrub near the roots, burnt it, dragged heavy

harrows about among the stumps, sowed the scratched surface, and the season being a good

one, reaped a first-rate crop. The process became known as "Mullenising," and

implements were made to carry it on. The most important of these is the stump-jumping

plough, which is claimed to have been the invention of a farmer named Charles Branson,

from whose drawings the first stump-jumper was made by Mr. J. W. Scott, of Alma. Several

machinists have adopted and improved upon the original idea, which has worked almost as

great a revolution in farming as the Ridley reaper. The modern implement ha a strong iron

frame, carrying three plough-shares attached to heavily-weighted levers. When they strike

a stump, root, rock, or other obstruction, they simply climb over it, instead of bringing

tie team up with a violent jerk. One ploughman can easily do the work of three, besides

dispensing with the aid of a driver. Within five years of this invention being made known,

more than half a million acres of scrub-lands that were formerly considered unsuitable for

agriculture were taken up by farmers, and its fame has spread far and wide. Across

the head of the gulf, and running a long distance north and south, is seen the Hummocks

Range, to surmount which the railway makes a complete zig-zag. As it climbs the slope the

view, looking southward on a clear day, is exceedingly, beautiful. The foreground is open,

well grassed, and park-like to the water’s edge. Beyond is the deep blue of the gulf,

which as it widens away to the right is only bounded by the horizon. On the farther shore

the white buildings of Port Wakefield seem to shine in the sunlight, contrasting strongly

with the mangroves that line the beach. Behind it, and to the north, are the extensive

plains that have been traversed. Ranges of hills form the background, and perhaps Mount

Lofty is dimly’ visible, though, as the crow flies, it is seventy miles away. From

the crest of the range there are easy descending gradients along a course nearly due west,

across grassy plains, through stretches of scrub, and past cultivated clearings, till

Kadina is reached, a hundred and seventeen miles from Adelaide.

Across

the head of the gulf, and running a long distance north and south, is seen the Hummocks

Range, to surmount which the railway makes a complete zig-zag. As it climbs the slope the

view, looking southward on a clear day, is exceedingly, beautiful. The foreground is open,

well grassed, and park-like to the water’s edge. Beyond is the deep blue of the gulf,

which as it widens away to the right is only bounded by the horizon. On the farther shore

the white buildings of Port Wakefield seem to shine in the sunlight, contrasting strongly

with the mangroves that line the beach. Behind it, and to the north, are the extensive

plains that have been traversed. Ranges of hills form the background, and perhaps Mount

Lofty is dimly’ visible, though, as the crow flies, it is seventy miles away. From

the crest of the range there are easy descending gradients along a course nearly due west,

across grassy plains, through stretches of scrub, and past cultivated clearings, till

Kadina is reached, a hundred and seventeen miles from Adelaide. The

town is well laid out with what will be a handsome square in the centre, and contains a

large number of very fine buildings that were erected when the mines were in full swing

and everything prosperous. Since their decadence, the prosecution of farming in the

surrounding district has done something to sustain business. Besides the railway from Port

Wakefield, there is another running thirty-three miles in a north westerly direction to

Snowtown, the centre of a large district, but despite these aids the revival of

copper-mining is the hope of the place. A mile away to the south, across the railway line,

a number of tall engine houses and a maze of winding-gear connected with the several

shafts denote the position of the Wallaroo, Kurilla, and other mines. The deposits of

copper were first brought to light by the burrowing operations of an inoffensive wombat.

He was summarily ejected, his hole enlarged, and Wombat shaft has become world-renowned.

Seven miles west from Kadina is Wallaroo Bay, a deep indentation in the coast of

Spencer’s Gulf forming an excellent harbour. It has ample wharfage accommodation and

a jetty sixteen hundred feet long, at which vessels of two thousand tons’ burden may

lie and load or unload in any weather, but the town itself is not much to boast of. A

cluster of chimneys and a perpetual cloud of smoke show the position of the smelting

works, which have thirty-six furnaces. A mountain containing tens of thousands of tons of

coal, on one side, and a still larger mountain of slag on the other, suggest the magnitude

of the work that is carried on. A tram-line running southward for eleven miles, mostly

through thick scrub, but with occasional glimpses of the sea, conducts to Moonta. Emerging

from the scrub the famous mines, with their tall engine-houses, slender winding-gear, and

mountainous heaps of refuse, are seen to the left. The town lies on a slope about a mile

nearer the sea, which renders its closely packed and stately buildings peculiarly

conspicuous. The most prominent of all is the Wesleyan Church, which both for

commodiousness and architectural style is worthy of a metropolis. As at Kadina, the

business places and public buildings were mostly erected when times were flush, and are on

an ambitious scale. Moonta is the commercial centre, for, though thousands of people live

on the mine property, there are no places of business allowed. The population fluctuates

with the prosperity of the mines, but at one time, before the depreciation in the price of

copper, Kadina, Wallaroo, and Moonta, with the neighbouring townships, had upwards of

twenty thousand inhabitants. The Moonta mine, without calling up any capital from its

shareholders, even for its early development, has paid in dividends more than a million

pounds sterling. Here and there amid the surrounding scrub engine-houses and other tokens

of mining ventures that are now abandoned may, be met with, but the payable cupriferous

area seems to be singularly limited. Southern Yorke’s Peninsula has few striking

features. Throughout its entire length of more than a hundred miles it is occupied by,

either squatters or farmers, and some parts are very productive. It has neither mountains

nor rivers, but in the south are number of salt lakes —glittering sheets of purest

white like roughened ice —sometimes several miles in circumference. Much of it is

lightly timbered with gum-trees or shea-oaks, but there are also open plains and patches

of dense scrub. The principal towns are Maitland, Minlaton, and Yorketown, and the bulk of

the produce usually finds its way from one or other of several small shipping places to

Port Adelaide.

The

town is well laid out with what will be a handsome square in the centre, and contains a

large number of very fine buildings that were erected when the mines were in full swing

and everything prosperous. Since their decadence, the prosecution of farming in the

surrounding district has done something to sustain business. Besides the railway from Port

Wakefield, there is another running thirty-three miles in a north westerly direction to

Snowtown, the centre of a large district, but despite these aids the revival of

copper-mining is the hope of the place. A mile away to the south, across the railway line,

a number of tall engine houses and a maze of winding-gear connected with the several

shafts denote the position of the Wallaroo, Kurilla, and other mines. The deposits of

copper were first brought to light by the burrowing operations of an inoffensive wombat.

He was summarily ejected, his hole enlarged, and Wombat shaft has become world-renowned.

Seven miles west from Kadina is Wallaroo Bay, a deep indentation in the coast of

Spencer’s Gulf forming an excellent harbour. It has ample wharfage accommodation and

a jetty sixteen hundred feet long, at which vessels of two thousand tons’ burden may

lie and load or unload in any weather, but the town itself is not much to boast of. A

cluster of chimneys and a perpetual cloud of smoke show the position of the smelting

works, which have thirty-six furnaces. A mountain containing tens of thousands of tons of

coal, on one side, and a still larger mountain of slag on the other, suggest the magnitude

of the work that is carried on. A tram-line running southward for eleven miles, mostly

through thick scrub, but with occasional glimpses of the sea, conducts to Moonta. Emerging

from the scrub the famous mines, with their tall engine-houses, slender winding-gear, and

mountainous heaps of refuse, are seen to the left. The town lies on a slope about a mile

nearer the sea, which renders its closely packed and stately buildings peculiarly

conspicuous. The most prominent of all is the Wesleyan Church, which both for

commodiousness and architectural style is worthy of a metropolis. As at Kadina, the

business places and public buildings were mostly erected when times were flush, and are on

an ambitious scale. Moonta is the commercial centre, for, though thousands of people live

on the mine property, there are no places of business allowed. The population fluctuates

with the prosperity of the mines, but at one time, before the depreciation in the price of

copper, Kadina, Wallaroo, and Moonta, with the neighbouring townships, had upwards of

twenty thousand inhabitants. The Moonta mine, without calling up any capital from its

shareholders, even for its early development, has paid in dividends more than a million

pounds sterling. Here and there amid the surrounding scrub engine-houses and other tokens

of mining ventures that are now abandoned may, be met with, but the payable cupriferous

area seems to be singularly limited. Southern Yorke’s Peninsula has few striking

features. Throughout its entire length of more than a hundred miles it is occupied by,

either squatters or farmers, and some parts are very productive. It has neither mountains

nor rivers, but in the south are number of salt lakes —glittering sheets of purest

white like roughened ice —sometimes several miles in circumference. Much of it is

lightly timbered with gum-trees or shea-oaks, but there are also open plains and patches

of dense scrub. The principal towns are Maitland, Minlaton, and Yorketown, and the bulk of

the produce usually finds its way from one or other of several small shipping places to

Port Adelaide. THE route lies up the valley of the Gilbert, which, after a few

miles, opens into a fertile plain gently sloping east and west from the river to the

ranges. It is three to four miles wide and perhaps twelve miles long, bare of timber, but

nearly every acre has been under the plough. Near Riverton the country is more broken, and

a forest of gum-trees is passed through just before reaching the town. Riverton is

sixty-two miles from Adelaide, and a bright, busy place of about six hundred inhabitants,

sheltered from the north and west by tree clothed hills, itself embowered in gardens and

plantations, and the centre of a prosperous region. Almost the same description will apply

to Saddleworth, five miles farther on, except that it is not so large and has more

picturesque surroundings. Manoora and Mintaro, which are the next succeeding stations, are

much smaller, but the whole of this run of twenty miles is exceedingly pretty. It has

nothing of the grand or romantic, but there is a succession of gently-swelling hills and

fertile vales, clad with verdure, adorned with trees, and every here and there a

substantial farm-house with its roomy outbuildings, smiling gardens, and prolific orchard.

It is beautiful in spring-time, when the tender green of the young wheat contrasts with

the chocolate-coloured fallows; and perhaps still more so, when for miles together even

the fences are concealed by the standing corn that has turned golden under the summer sun,

and the hum of the reaper is heard in the land. The line has gradually ascended till at

Mintaro it is thirteen hundred and sixty-nine feet above the sea level. Here the timber is

left behind, the soil becomes less fertile, and another plain is opened twenty miles or

more in length, flanked by bare-looking hills that recede to the right ‘and left.

They are more abrupt in their outlines, running up to narrower ridges and sharper peaks,

introducing an element of picturesqueness and conveying a suggestion of mineral wealth. At

Farrell’s Flat, eighty-seven miles from town, extent rather than variety is the chief

feature of the landscape. The vision ranges over a shallow valley bounded in the distance

by serrated hills, and containing at least two hundred square miles suitable for either

agriculture or pasturage, most of which is occupied by sheep-runs.

THE route lies up the valley of the Gilbert, which, after a few

miles, opens into a fertile plain gently sloping east and west from the river to the

ranges. It is three to four miles wide and perhaps twelve miles long, bare of timber, but

nearly every acre has been under the plough. Near Riverton the country is more broken, and

a forest of gum-trees is passed through just before reaching the town. Riverton is

sixty-two miles from Adelaide, and a bright, busy place of about six hundred inhabitants,

sheltered from the north and west by tree clothed hills, itself embowered in gardens and

plantations, and the centre of a prosperous region. Almost the same description will apply

to Saddleworth, five miles farther on, except that it is not so large and has more

picturesque surroundings. Manoora and Mintaro, which are the next succeeding stations, are

much smaller, but the whole of this run of twenty miles is exceedingly pretty. It has

nothing of the grand or romantic, but there is a succession of gently-swelling hills and

fertile vales, clad with verdure, adorned with trees, and every here and there a

substantial farm-house with its roomy outbuildings, smiling gardens, and prolific orchard.

It is beautiful in spring-time, when the tender green of the young wheat contrasts with

the chocolate-coloured fallows; and perhaps still more so, when for miles together even

the fences are concealed by the standing corn that has turned golden under the summer sun,

and the hum of the reaper is heard in the land. The line has gradually ascended till at

Mintaro it is thirteen hundred and sixty-nine feet above the sea level. Here the timber is

left behind, the soil becomes less fertile, and another plain is opened twenty miles or

more in length, flanked by bare-looking hills that recede to the right ‘and left.

They are more abrupt in their outlines, running up to narrower ridges and sharper peaks,

introducing an element of picturesqueness and conveying a suggestion of mineral wealth. At

Farrell’s Flat, eighty-seven miles from town, extent rather than variety is the chief

feature of the landscape. The vision ranges over a shallow valley bounded in the distance

by serrated hills, and containing at least two hundred square miles suitable for either

agriculture or pasturage, most of which is occupied by sheep-runs. Villages and towns occur at shorter intervals along this road than anywhere

else in the north. Four miles from Auburn comes Leasingham, three miles further is

Watervale, and Penwortham and Seven Hills are only two miles apart. The scenery throughout

is charming. Willows fringe the watercourses, in some places patriarchal gum-trees are

left standing, the slopes are fertile cornfields, and the flats luxuriant meadows.

Cottages half-hidden by climbing roses and other creepers,’ blooming gardens and

vineyards and orchards in full bearing, are frequent for miles on either hand. The towns,

though small, are thriving, and the number of substantial stone buildings, public as well

as private, is a healthy indication. Over the hills, about two miles to the east of Seven

Hills, is a large Roman Catholic college, and near by is an exceedingly neat and

well-finished church. The property includes a large vineyard, with spacious wine-vaults,

and the produce is celebrated throughout the neighbourhood. Still further in the same

direction is the town of Mintaro, on the slope of the range, and close to it are large

slate quarries, whence flags of excellent quality are exported to all parts of Australia.

Villages and towns occur at shorter intervals along this road than anywhere

else in the north. Four miles from Auburn comes Leasingham, three miles further is

Watervale, and Penwortham and Seven Hills are only two miles apart. The scenery throughout

is charming. Willows fringe the watercourses, in some places patriarchal gum-trees are

left standing, the slopes are fertile cornfields, and the flats luxuriant meadows.

Cottages half-hidden by climbing roses and other creepers,’ blooming gardens and

vineyards and orchards in full bearing, are frequent for miles on either hand. The towns,

though small, are thriving, and the number of substantial stone buildings, public as well

as private, is a healthy indication. Over the hills, about two miles to the east of Seven

Hills, is a large Roman Catholic college, and near by is an exceedingly neat and

well-finished church. The property includes a large vineyard, with spacious wine-vaults,

and the produce is celebrated throughout the neighbourhood. Still further in the same

direction is the town of Mintaro, on the slope of the range, and close to it are large

slate quarries, whence flags of excellent quality are exported to all parts of Australia. Several

engine-houses are still standing, with their valuable machinery carefully protected, and

others are dismantled. They look as if they might stand for ever, some of their walls are

six feet thick, of solid masonry built with massive stones measuring as much as seven feet

by three. Huge water-wheels connected with batteries of stampers, long lengths of

"launders" that are dropping to pieces, immense capstans with eighteen-inch

cables coiled round them, and sturdy trees growing between their arms, lofty shears still

bearing, as a vane the orthodox figure of a miner with pick and gad, jigging machines and

purifiers that need renovating themselves, old water reservoirs, in which brushwood is

growing, rusty beams of pumping-engines, iron piping and parts of machinery that has been

taken to pieces lying in confused heaps, tottering poppet-heads and dilapidated sheds and

workshops, all combine to produce a melancholy impression. The yawning gulf and the

mountains of refuse that have come out of it tell of former industry. Once this little

hollow was as full of life as an anthill, for more than eleven hundred men and boys found

employment in it; but now all is silence, desolation, and decay.

Several

engine-houses are still standing, with their valuable machinery carefully protected, and

others are dismantled. They look as if they might stand for ever, some of their walls are

six feet thick, of solid masonry built with massive stones measuring as much as seven feet

by three. Huge water-wheels connected with batteries of stampers, long lengths of

"launders" that are dropping to pieces, immense capstans with eighteen-inch

cables coiled round them, and sturdy trees growing between their arms, lofty shears still

bearing, as a vane the orthodox figure of a miner with pick and gad, jigging machines and

purifiers that need renovating themselves, old water reservoirs, in which brushwood is

growing, rusty beams of pumping-engines, iron piping and parts of machinery that has been

taken to pieces lying in confused heaps, tottering poppet-heads and dilapidated sheds and

workshops, all combine to produce a melancholy impression. The yawning gulf and the

mountains of refuse that have come out of it tell of former industry. Once this little

hollow was as full of life as an anthill, for more than eleven hundred men and boys found

employment in it; but now all is silence, desolation, and decay.

The line to Cockburn has acquired unexpected

importance since it was opened through the marvellous metalliferous discoveries in the

Barrier Ranges. For a considerable distance it passes through hilly country, diversified

by gum-trees, pines, silver wattle, and mallee, among Which there is some good

agricultural land, and then for about a hundred and twenty miles it is nearly all

salt-bush, only fit for sheep-runs, dreary and monotonous. About halfway and some twenty

miles or so to the north of the line are the Teetulpa goldfields. The geological formation

of the ranges that run north and south through the colony stretches out a long and wide

promontory eastward. There are primary and plutonic rocks, and for at least thirty miles

they are proved to be auriferous. Were the richness of the field commensurate with its

extent, there would be here a second Ballarat. Sanguine investors say that such will yet

be the case, and the workings at the Waukaringa and other mines are held to encourage the

belief. The railway is constructed forty miles further —to Silverton and Broken Hill

in New South Wales. Since the earlier parts of this work were published these places have

sprung into importance by the development of the richest silver-mines in the wide world.

The argentiferous area is extensive and fabulously rich. The mines are numerous, but

Broken Hill is the glory of the region. The formation of the hill itself, with its steeply

inclined slopes and rugged crest of black, calcined-looking boulders, is most impressive

to the spectator. A descent into the mine is like a visit to the palace .of a silver king.

The town is growing with phenomenal rapidity, and it is believed that ere long it will

contain a larger population than that of any other outside the capitals of the several

colonies. Northwards, there is a stanniferous belt at least twenty-eight miles long and

three miles wide. There is a slaty formation intersected by granite dykes, of which fifty

or more are proved to be tin bearing. Their value is at present only conjectural. In some

seasons of the year these ranges are very beautiful. The hills are picturesque, and the

ground is covered by a brilliant carpet of wild flowers, among which the gorgeous Sturt

pea is conspicuous, acres together being sheeted by its scarlet and black clusters of

bloom.

The line to Cockburn has acquired unexpected

importance since it was opened through the marvellous metalliferous discoveries in the

Barrier Ranges. For a considerable distance it passes through hilly country, diversified

by gum-trees, pines, silver wattle, and mallee, among Which there is some good

agricultural land, and then for about a hundred and twenty miles it is nearly all

salt-bush, only fit for sheep-runs, dreary and monotonous. About halfway and some twenty

miles or so to the north of the line are the Teetulpa goldfields. The geological formation

of the ranges that run north and south through the colony stretches out a long and wide

promontory eastward. There are primary and plutonic rocks, and for at least thirty miles

they are proved to be auriferous. Were the richness of the field commensurate with its

extent, there would be here a second Ballarat. Sanguine investors say that such will yet

be the case, and the workings at the Waukaringa and other mines are held to encourage the

belief. The railway is constructed forty miles further —to Silverton and Broken Hill

in New South Wales. Since the earlier parts of this work were published these places have

sprung into importance by the development of the richest silver-mines in the wide world.

The argentiferous area is extensive and fabulously rich. The mines are numerous, but

Broken Hill is the glory of the region. The formation of the hill itself, with its steeply

inclined slopes and rugged crest of black, calcined-looking boulders, is most impressive

to the spectator. A descent into the mine is like a visit to the palace .of a silver king.

The town is growing with phenomenal rapidity, and it is believed that ere long it will