Atlas Page 68

By W. H. Traill

| Northward from Moreton Bay |

Maryborough |

REFERENCE has repeatedly been made in previous pages to Ipswich. In the earlier days

after separation, the favourite and most convenient access from Brisbane was by river

steamer, although the land journey was shorter by half, and the road fairly good and well

served by the ubiquitous Cobb’s coaches. The trip by river was altogether charming,

save on winter mornings, when "an eager and a nipping air," and oft times a

bitter fog, destroyed all enjoyment. But the Queensland winter is brief, and its noondays

are sunny. It is, indeed, the most delightful season conceivable; the sky is blue and

cloudless; a fresh breeze blows from the west; at night the stars, and the moon in its

season, shine with splendid brightness through the lucid atmosphere. A sharp

frost touches the uplands, and at daybreak the grass is white with rime, which crackles

underfoot. Sometimes even a thin flake of ice crusts water left exposed in vessels and the

surface of shallow pools. The air invigorates the blood, and exhilarates like champagne.

As the sun climbs the sky, a genial warmth is diffused. The bushman, chilled with camping

out, and frigid to the very marrow of his bones in consequence of wading at day-dawn

through the long, rimy grass to catch his horse, is sustained and consoled by the

certainty that in a few hours the sun will beam benevolently and suffuse his frame with

warmth.

But to resume. A summer morning voyage from Brisbane to Ipswich was a delightful experience. The broad bosom of the Brisbane River reflected sky and shore. Fresh vistas presented themselves as each curve was rounded by the swift steamer, the " Ipswich," or the more commodious although less speedy, "Emu" —now carrying passengers between Sydney and Manly Beach. When the steamer turned from the Brisbane River to ascend the Bremer, the navigation assumed a new and strange aspect. The creek is narrow and in places very tortuous. Here and there it seemed as though it terminated, but a sudden, sharp curve exposed a fresh reach, and the steamer swung sharply round the angle, assisted by vigorous shoves of poles, wielded by men in the bows, pushing against the bank. To turn a craft of any size right round was impossible until the "basin" was reached. To this basin Ipswich owes its early development. Here vessels could be swung round, and beyond this the creek ceased to be navigable.

The river trip is no longer made by passenger steamers. The railway now connects Ipswich with Brisbane, about an hour being occupied in covering the twenty-five miles. The original settlement was on the Bremer, at the base of a fine ridge of rich, black soil with outcroppings of limestone, which first attracted the notice of Logan in his exploration of the Bremer. A handsome mansion, standing in its own grounds, facing the river here, looks down upon the probable landing-place of the first visitors. This dwelling is the residence of Mr. George Thorn, eldest son of Sergeant Thorn, once in charge of the guard of soldiers stationed here to protect the men labouring at the lime-kilns. Mr. Thorn remained, after obtaining his discharge, to see a thriving town arise where once the natives skulked, and to own large properties in that town, and extensive freeholds in the rich flats where the government herds and flocks used to graze; and ultimately to see three of his sons simultaneously in the parliament of Queensland, and one of them attain the premiership. The greater part of the slopes of the limestone ridge facing the town, which is planted chiefly in and on the other side of a deep valley, have been happily reserved from alienation, and now form a very valuable recreation ground, whence the greater part of the town is overlooked. The principal street was once the main road to the Darling Downs. At right angles it is traversed by others, of which the most important leads down to the frontage of the Bremer basin. Prior to the construction of railways, Ipswich was a place of much importance, and these two streets especially were the scene of perpetual bustle. Scores of bullock-drays here "dragged their slow length along," in Alexandrine fashion, laden with supplies direct from the wharves or from the stores which lined these streets. Later, a season of deep depression afflicted the town. The railway starting hence, inland, had shifted the terminal point of bush conveyance far to the west. But settlement progressed apace in the rich agricultural and pastoral lands in the neighbourhood, and gradually its prosperity returned, established upon a sound and stable basis. Ipswich has the appearance of being the provincial town, which, in fact, it is. A commodious hospital perched on a breezy hillside is a prominent feature, and St. Paul’s Anglican church, which is centrally situated, is an elegant structure. The Grammar School has a tasteful building on a very fine site. A fine iron bridge spans the Bremer above the basin, and maintains communication with the suburb on the other bank during even the heaviest floods, which rise more than sixty feet above the ordinary level of the creek. The population numbers about eight thousand.

From the railway runs westward through rich forest flats, and over a

minor hill system, till it reaches the foot of the main coast range. Here a section of

great interest commences. Instead of the zig-zag method of overcoming the cordillera

adopted on the Blue Mountains in New South Wales, the Queensland railway engineers adopted

the plan of contouring that is to say, following the outline of the hills by a constant

ascending grade along their face. The line occasionally burrows in tunnels through spurs

which project too far to be more economically contoured, and similarly leaps, by means of

light but substantial iron bridges, over ravines and gullies, often of startling depth.

The downward prospect into the ferny tangle of these ravines from points of vantage whence

the traveller regards, from the railway carriage, the tops of trees springing from the

round hundreds of feet below, is exceedingly picturesque. Raising his eyes, the beholder

in an instant transfers his range of vision to an horizon remote a hundred miles, over a

middle distance composed of a sea of forest vegetation motionless and sombre-hued.

Suddenly the train alters its style of progression. In lieu of slowly conquering an up-grade, as it has been doing for some seventeen miles, it begins to descend at enhanced speed a gentle declivity, and a view more circumscribed and entirely altered presents itself. The mountain barrier has been overcome, and the great plateau of the Darling Downs has been reached. Everything is changed in an instant. The character of the timber, its distribution over the face of the country, nay, the very soil is different. In a few minutes Toowoomba, the capital of the Downs, is reached. Still the real characteristic downs country has not been seen. Toowoomba, close to the brink of the range, is situated on the forest-clad skirts of the Downs proper, which have been already described.

The town of Toowoomba was not laid out until after

separation. The inconvenience and meanness of the narrow streets, which Brisbane, Ipswich,

and other of the earliest Queensland towns owe to the lack of foresight and judgment of

Governor Gipps and others, had already been recognised when Toowoomba had to be defined.

The consequence was a generous provision for streets, and Ruthven Street, Toowoomba, is

not surpassed, as regards its noble lateral dimensions, by Bourke or Collins Streets in

Melbourne, while it surpasses both in the indefinite prolongation which ultimately loses

itself in the forest primeval. The parallel cross streets are laid out on the same liberal

scale, and afford provision for the future development of a majestic city. As yet, it must

be admitted the great width of the thoroughfares is not without its drawbacks. Toowoomba

is planted on the margin of extensive swampy depressions. The soil is of surpassing

richness, alike as regards its fecundity, its colour, and its tenacity. In wet weather its

deep, red-brown mud clings to every boot or wheel which comes in contact with it, and in

dry seasons a red dust of a most searching quality invades every domicile. White horses in

Toowoomba are tempered to a subdued chestnut tinge, white houses gently blush for the

soil. White costumes, such as are summer wear below the range, are here impossible. The

municipal authorities find the revenues of a moderate population inadequate to form and

maintain the full width and side-walks of their extensive boulevards; hence the town

cannot be described as handsome, nor is beauty lent to it by an architectural splendour.

Country town is stamped upon its present aspect, while a magnificent city is promised by

the design of its founders and by the extraordinary fertility of the surrounding district.

The population is about seven thousand. The town has gas-works and a system of water

supply. Its progress has been considerably impeded by causes which operate, more or less,

against all the towns on the Darling Downs. Of these, the principal are the frequent

destruction of the wheat crops by "rust," and the locking up of vast tracts of

magnificent land, treeless and inviting to the plough, by large freehold pastoralists.

At Toowoomba the railway bifurcates. One line proceeds due west towards the boundless tracts of the Maranoa and Warrego; the other, turning to the south, makes a connection with the railways of New South Wales, only a gap of a few miles remaining in 1887 to be filled-in in order to complete a junction which will shortly give uninterrupted railway communication from Adelaide to Brisbane. On the southern .arm stands the pretty little town of Warwick, one of the most picturesque in southern Queensland. Its situation is not far from Mr. Patrick Leslie’s first stationary camp in the Darling Downs district. Warwick is the centre of an agricultural and pastoral district, and stands amidst the timber in the ridgy country bordering the Downs. The soil around is rich and black, but the town itself is planted on a gravelly stratum which keeps its roads ever tidy and clean. A central park of limited dimensions lends a special and unusual attraction to the urban vistas. Being less elevated than Toowoomba, the winter climate is not quite so raw and bleak. Warwick is distant from Brisbane about one hundred and sixty-six miles southwest, and supports a population of a little over three thousand. A branch railway thence leads off to Killarney, twenty-eight miles, a farming settlement nearer the main range.

The main trunk line continues to the New South Wales border via Stanthorpe, a little township which sprung into existence in 187o as the centre of the alluvial tin deposits then discovered, and which has not, since its early boom, made much progress. It is a primitive little place, flanked by a granite hill, and surrounded by alluvial tin workings in the Severn River and the creek which preserves its original unromantic name of Quart Pot. The workings are, however, now mostly exhausted, and lodes of tin have not, up to the present, been found in the locality.

The other branch of railway which proceeds from Toowoomba, besides a short subsidiary

line to Highfields, an agricultural district on the slopes of the main range, is the

western line which, passing through the cream of the northern Downs, touches the town of

Dalby —locally styled in appropriately figurative speech the City of the Plains

—and stretches away to Roma on the Maranoa, and thence to Charleville on the Warrego.

The total distance from Brisbane is about five hundred

and twenty miles. A further extension to the Paroo is projected and this line appears

destined to connect with prolongations of the interior railway systems of New South Wales

and of South Australia, where the territories of the three colonies touch one another.

Neither of these towns calls for special description. Each has a population under two

thousand. Roma, three hundred and seventeen miles inland from Brisbane, already shows

indications of future agricultural and aboricultural development. Grape vines flourish and

some farming exists, but the rainfall so far inland is intermittent, storage and

irrigation are not practiced, and as yet the town is mainly to be regarded as the centre

of a pastoral district.

RETURNING to Brisbane and voyaging north from Moreton Bay, the coast presents a somewhat monotonous aspect, although to the reader of early voyages it bristles with reminiscences of peril and research. After passing the southern corner of Bribie island, Skirmish Point —so called by Flinders during his voyage of examination to Hervey’s Bay, on account of a conflict at this spot with aborigines —the Glasshouse Mountains loom above the dreary stretches of sand, the sad, sombre-hued swamps, and the low, scrub-covered flats, relieved here and there by isolated hummocks and furze-clad dunes, behind which darkle little pools of sea-water hurled thither by the hissing breakers, boiling and foaming on the sunken rocks whose seething white line marks the danger most to be feared by the coasting mariner. Of these Glasshouse Mountains, Wyneck towers into the sky and presents the appearance of an exaggerated hay-cock upon which a giant had been romping and had thereby flattened its top somewhat. Leaving Bribie Island astern and voyaging northward, a series of beautiful salt-water lakes lies behind the low hills between Moreton Bay and Double Island Point. The headland just mentioned forms the southern bluff of the opening known as Wide Bay, the northern limit being the southern portion of Great Sandy Island, which stretches northward to Indian Head, Sandy Cape, and Breaksea Spit, and by its shelter forms the extensive roadstead of which the southern area is termed Wide Bay and the northern Hervey’s Bay. The entire nomenclature is Captain Cook’s, and is so descriptive that it is scarcely necessary to further delineate the features of the places the great navigator designated. Great Sandy Island is also known as Frazer Island, in consequence of the enforced and tragic sojourn there, already detailed, of Mrs. Frazer, as a castaway among the natives, whose visible numbers at the time of his visit induced Cook to give its name to " Indian" Head.

The channel leading into Wide Bay is narrow, shifting, and tortuous. On the bar a tremendous sea breaks during heavy easterly or south-easterly gales, and at such times it is not uncommon for quite a little squadron of coasting steamers and smaller craft to be anchored inside this weather-wall, awaiting X subsidence of the surf before venturing to sea. On such occasions the passengers beguile the time by interchanging visits from vessel to vessel, and even by boat-trips ashore to Frazer Island. Defended by the bar, the roadstead remains smooth while the huge breakers roar and foam to seaward.

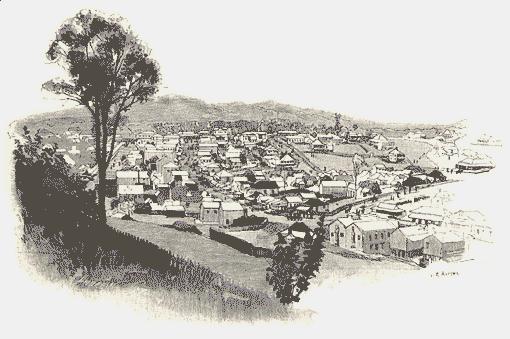

MARYBOROUGH.INTO the shallow and placid waters of Wide Bay the Mary River disembogues, and about twenty-five miles from its mouth is situated the town of Maryborough, a thriving settlement of some thirteen thousand inhabitants. Maryborough is planted on the banks of the river, at a sharp curve. As the coastal terminus of several short railways, and the port which ministers to the Gympie goldfield and the coal measures of the Burrum River, flowing into Hervey’s Bay, a little further north, it is a considerable place, with prospects still more considerable. The stage of architectural pretension has not yet been reached by Maryborough, which, nevertheless, derives a certain picturesqueness from its situation, and from the very irregularities and primitiveness of its structures, and the frequent occurrence of foliage among, the houses. The premises of the various banking institutions and the government offices constitute the chief embellishments. The streets, of which the principal are Kent Street, Adelaide Street, and Wharf Street, are of moderate width. The scrubs which originally clothed the alluvial tracts on the riverbanks were once prolific of cedar and pine, of which the supply is not yet exhausted. The saw mill industry is not at present as flourishing as it was some years ago, and of four mills in the neighbourhood, two only, are now at work. Two extensive engineering factories and two sash and door factories are among the industrial establishments, while on the river at different points are several important saw-mills and sugar mills, the last-named crushing cane supplied by a multitude of plantations, chiefly tilled by Kanaka labourers.

Maryborough was first settled on June 4th, 1848, on which date Mr. Aldridge, who still survives, a respected and now wealthy citizen, and Mr. Palmer, also an esteemed and successful colonist, simultaneously crossed the river from the south bank on a raft made of the trunk of a pine-tree split in halves. They established themselves at what is known as the old township, distant by river about seven miles up a bend, and by land some two and a half miles, from the present town of Maryborough.

At that time, there was squatted on the south bank a shanty-keeper named Furber, at a place named Girker, which had been an outlying sheep station belonging to a run occupied by Mr. John Eales, of the Hunter River, New South Wales. The run had been abandoned, owing to bad times and the ferocity of the natives, but Furber had remained, ministering to the spirituous necessities of adventurous parties of timber-getters who, carrying their lives in their hands, pursued their occupation, scattered through the scrubs. Furber himself had already sufficiently experienced the risks which attended frontier settlement at that period. He now and then got some work out of the natives. On one occasion he had a blackfellow digging a post-hole, while he, close by, was squaring a post with a broadaxe. The savage seeming awkward at his task, Furber went to shew him how to dig. He seized the spade, thoughtlessly handing the axe to the native while he endeavoured teach him. As he stooped over his work, the treacherous aboriginal dealt him a tremendous blow on the neck with the axe, nearly severing his head from his shoulders, and incontinently bolted. Furber, on coming to his senses, managed to bandage his wound after a fashion, to catch and saddle his horse, and actually rode all the way to Ipswich —a distance by the then roads of not less than one hundred and fifty miles —for surgical treatment. He recovered, and beyond a shocking gap in his neck seemed none the worse, surviving for years; he was, however, together with his son-in-law, ultimately assassinated by the blacks while timber-getting in a scrub at Tinana Creek, a tributary of the Mary. It is at the junction of this creek with the Mary that for many years resided Mr. Bidwell, the first Land Commissioner of the Wide Bay district, whose name is handed down by the botanic style of the bunya-bunya tree —Araucaria Ridwelli —he having been the first to send seeds or plants to the Kew botanical gardens, whence he was originally despatched on a botanising expedition to the Moreton Bay settlement. As a matter of fact, Mr. Andrew Petrie had plants of the bunya pine growing in his garden at Brisbane earlier than the date of Mr. Bidwell’s visit to the Bunya Mountains. The latter gentleman was buried in the grounds surrounding his residence at Tinana Creek. We are not aware whether his last resting-place can still be distinguished.

Old Maryborough has a host of traditions attached to

it which local journalists would do well to gather and preserve. One of the most

characteristic we have knowledge of is derived from the report of a Queensland

parliamentary commission relative to the native police. Therein are materials for a weird

sketch of legal proceedings against aboriginal offenders in 1860. By some individual of

that doomed race, an "outrage," as it was customary to designate every ill-deed

of the blacks, had been committed, and Lieutenant Wheeler, commanding a detachment of

native troopers, was charged with the apprehension of the offender. The officer had

information that his man was among a mob of blacks camped close by the township, and

forthwith made a cavalry raid upon the encampment. Several natives bolted out of their

gunyahs in mortal terror, and then the sport afforded the townsmen became very exciting

indeed. The hunted black fellows —who very likely had been chopping, wood for

Maryborough matrons a few hours before —dashed away for their lives in various

directions, the troopers galloping after them and firing as they rode. One fugitive

scampered through the verandah of the residence of the Collector of Customs, Lieutenant

Wheeler after him, and reaching the river plunged in and swam for the opposite bank; but

feeling the officers of the law procured a boat and chased the man, firing the while. The

slaughter of a few blacks more or less did not apparently disturb the townsmen. It is one

of the incidents most eloquent respecting the condition of public feeling at the period

that the citizens of Maryborough marked their sense of the conduct of Lieutenant Wheeler

on this occasion by assembling together and with ceremonious enthusiasm solemnly

presenting that meritorious officer with a sword of honour —we might not

inappropriately have written, a sword of horror.

Old Maryborough has a host of traditions attached to

it which local journalists would do well to gather and preserve. One of the most

characteristic we have knowledge of is derived from the report of a Queensland

parliamentary commission relative to the native police. Therein are materials for a weird

sketch of legal proceedings against aboriginal offenders in 1860. By some individual of

that doomed race, an "outrage," as it was customary to designate every ill-deed

of the blacks, had been committed, and Lieutenant Wheeler, commanding a detachment of

native troopers, was charged with the apprehension of the offender. The officer had

information that his man was among a mob of blacks camped close by the township, and

forthwith made a cavalry raid upon the encampment. Several natives bolted out of their

gunyahs in mortal terror, and then the sport afforded the townsmen became very exciting

indeed. The hunted black fellows —who very likely had been chopping, wood for

Maryborough matrons a few hours before —dashed away for their lives in various

directions, the troopers galloping after them and firing as they rode. One fugitive

scampered through the verandah of the residence of the Collector of Customs, Lieutenant

Wheeler after him, and reaching the river plunged in and swam for the opposite bank; but

feeling the officers of the law procured a boat and chased the man, firing the while. The

slaughter of a few blacks more or less did not apparently disturb the townsmen. It is one

of the incidents most eloquent respecting the condition of public feeling at the period

that the citizens of Maryborough marked their sense of the conduct of Lieutenant Wheeler

on this occasion by assembling together and with ceremonious enthusiasm solemnly

presenting that meritorious officer with a sword of honour —we might not

inappropriately have written, a sword of horror.

Higher up the Mary River are several townships, and, connected by railway, the important mining centre of Gympie, with a population of nearly eight thousand. The origin of this town has already been described. At the present time, it contains nearly two thousand dwellings.

click here to return to main page