|

Early Experiences of Two States That Offer Full Public Funding

for Political Candidates

|

Highlights of GAO-03-453,

a report to Congressional Committees -

May 2003

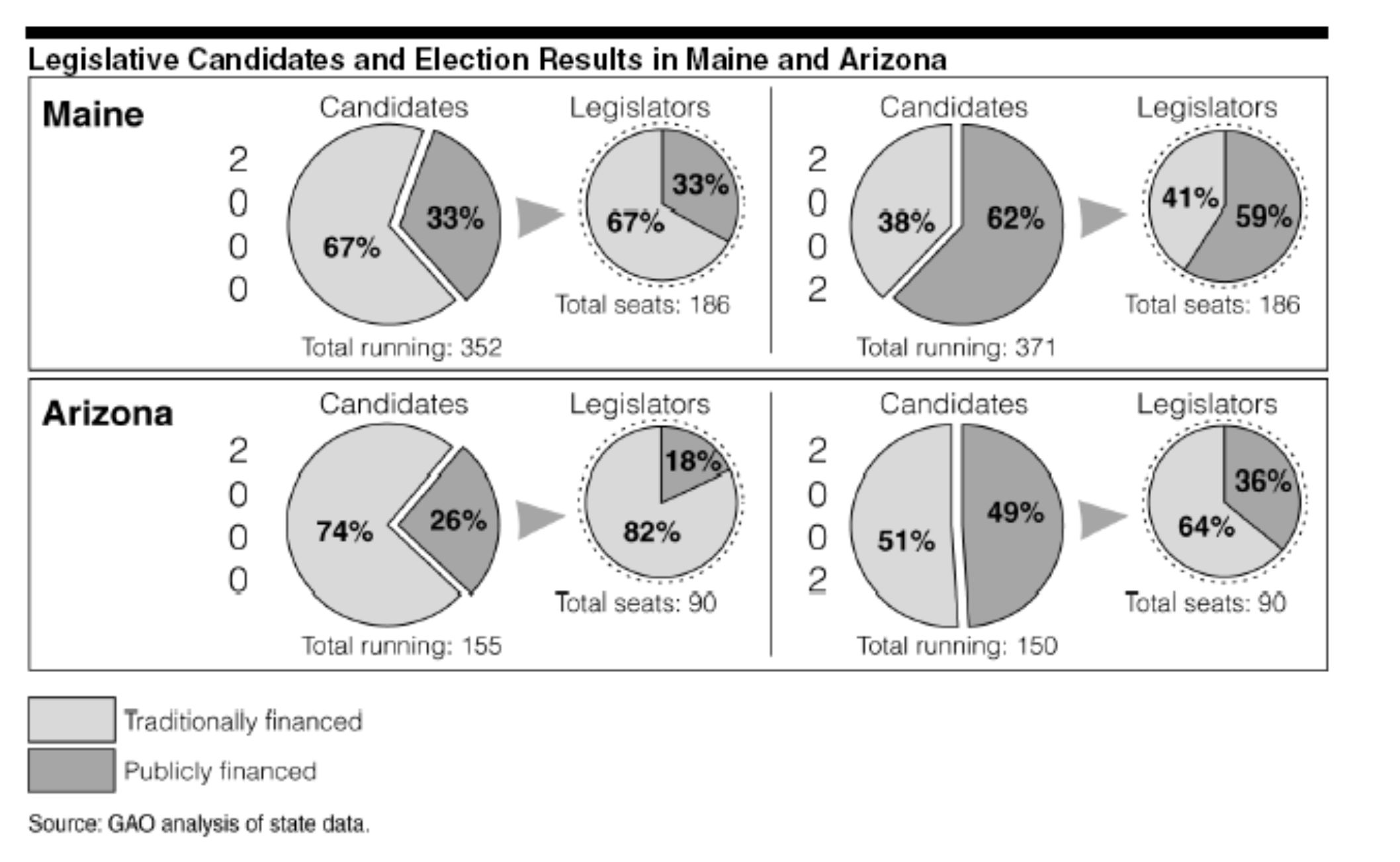

In 2000 and 2002, Maine and Arizona held the nation’s

first elections under

voluntary programs that offered full state funding for political candidates

who ran for legislative and certain statewide offices. The goals of these

programs, passed as ballot initiatives by citizens in these states, included

increasing electoral competition and curbing increases in the cost of

campaigns.

Congress has considered legislation for public financing

of congressional elections nearly every session since 1956, although no law

has been enacted. In the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (P.L. 107-155

(2002)), Congress mandated that GAO study the results of the unique public

financing programs in Maine and Arizona.

For the 2000 and 2002 elections in Maine and Arizona,

this report provides:

|

•

Statistics on the number of candidates who chose to campaign with public

funds and the number who were elected. |

|

• Observations, based on limited data, regarding the extent to which the goals

of the public funding programs were met. |

www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-03-453

To view the full product, including the scope and methodology, click on

the link above. For more information.

|

In both

Maine

and Arizona,

the number of legislative

candidates who chose to use

public financing for their campaigns increased greatly

from 2000 to 2002. 59 percent of Maine’s and 36

percent of Arizona’s current legislators successfully ran as publicly

financed candidates in the 2002 election. Also, in Arizona’s 2002 election,

publicly financed candidates won seven of the nine

available seats in races for statewide offices, including Governor.

|

In comparing the

2000 and 2002 elections to those in 1996 and 1998, GAO’s findings regarding

changes in electoral competition were inconclusive.

Various measures—contested races (more than one candidate per race),

incumbent reelection rates, and incumbent victory margins—reflect mixed

results. Also, these results may have been affected by term limits,

redistricting, and other factors.

Average legislative candidate spending decreased in

Maine but increased in Arizona in 2000 and 2002, compared to previous years.

Further, particularly in 2002, both states experienced

increases in independent expenditures—a type of campaign spending whereby

political action committees or other groups expressly support or oppose a

candidate. The extent of spending for public policy messages without

explicit election advocacy is not known.

In sum, with only two elections from which to observe legislative races and

only one election from which to observe most statewide races,

it is too early to draw causal linkages to

changes, if any, that resulted from the public financing programs in the two

states. |

For the latest in Public

Financing in the States go to

http://www.commoncause.org/states/CFR-financing.htm For the latest in Public

Financing in the States go to

http://www.commoncause.org/states/CFR-financing.htm

Fourteen states provide direct public financing to candidates. An additional ten

states provide minimal public financing to candidates and/or political parties,

generally funded through taxpayer contributions to political parties through

their tax returns

(add-ons*).

Who is eligible for public financing?

|

Gubernatorial candidates: |

Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, Vermont |

|

Statewide office candidates: |

Florida, Rhode Island |

|

Statewide & legislative candidates: |

Arizona, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, Wisconsin |

|

Political party designated by taxpayer: |

Alabama, Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, New Mexico, North Carolina,

Rhode Island, Utah, Virginia |

|

Political party (according to distribution formula): |

California, Indiana, Ohio |

What is the source of the public funds?

|

Tax check-off: |

Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota,

New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, Utah, Wisconsin

|

|

Tax add-on : |

Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Maine, Maryland, Nebraska, North

Carolina, Vermont, Virginia |

|

Appropriations: |

Florida, Hawaii, Kentucky, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, Rhode Island

|

|

Other Sources: |

Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Vermont |

Brief Summaries of State Public Financing Laws

Fourteen states provide public financing directly to candidates, but the laws

differ as to how funding is provided and to which candidates. Following are

brief summaries of the public funding systems in those states and links to the

enforcement agency and the text of the statute.

-

Arizona Arizona

In November 1998, Arizona voters passed the Arizona Clean Elections Act, which

provides full public funding for statewide and legislative candidates who meet

a threshold requirement to raise a certain number of $5 contributions from

voters. The public funds come from a variety of sources, including a tax

checkoff, voluntary contributions and a surcharge on civil and criminal

penalties.

Florida

Under Florida law, candidates for governor and other statewide offices who

raise a threshold amount of money and agree to spending limits are eligible

for public matching funds. Contributions of $250 or less from individuals are

matched 1-to-1 with public funds. Also, if a candidate exceeds the voluntary

spending limit, their opponent is eligible to receive additional public funds

equal to the amount by which the limit has been exceeded.

Hawaii

Hawaii's public financing system provides funding to all candidates who agree

to a voluntary spending limit. Candidates are provided with public funds

equaling 20 percent or 30 percent of the spending limit, depending on the

office. The source of the funding is general appropriations and an income tax

checkoff.

Kentucky

Under Kentucky law, gubernatorial candidates who agree to spending limits are

eligible for public matching funds once they have raised amount in private

contributions of $500 or less. After reaching the qualifying threshold,

candidates receive $2 in public funds for every $1 in private funds.

Maine

In November 1996, voters in Maine approved a ballot initiative, the Maine

Clean Election Act, establishing a system of public financing and voluntary

spending limits for all state offices. Candidates who raise a threshold number

of small contributions from registered voters in their district and agree not

to raise any more private money qualify for a fixed amount of public financing

for their campaign.

Maryland

Maryland's public financing system provides matching funds (1:1 match) for

candidates for governor and lieutenant governor in the primary and general

elections. The source of the funds are contributions from taxpayers (add-on)

and revenue from fines related to the public financing law.

Massachusetts

In November 1998, Massachusetts voters passed an initiative providing a fixed

amount of public funding to candidates who: (1) raised threshold number of $5

to $100 contributions from voters in their district, (2) refused contributions

in excess of $100 and (3) abided by an aggregate limit on private

contributions. The ratio of public-to-private money for participating

candidate would be about 80-to-20. The bill also would prohibit national

parties from transferring soft money into the states and would require

candidates to file campaign finance reports electronically.

Michigan

Enacted in the 1970s, Michigan's public financing system provides

gubernatorial candidates who agree to a spending limit with a flat grant for

the general election and a 2:1 match for small contributions (under $100) in

the primary.

Minnesota

Minnesota's public financing system was enacted in the 1970s and significantly

reformed in 1993. It was the first state to provide public financing for both

legislative and gubernatorial candidates and is generally considered one of

the most successful campaign finance systems in the country. Candidates who

agree to a spending limit receive public funding equal to 50% of the limit.

Public funds come from a tax checkoff that allows taxpayers to direct those

funds to a qualified political party and from an annual appropriation. In

addition, a unique program allows anyone contributing up to $50 to a party

receives a refund from the state.

Nebraska

Nebraska passed a unique public financing law in 1992. The system provides

public funds to legislative candidates who agree to a voluntary spending limit

and whose opponent exceeds the spending limit. If sufficient funds are

available, statewide candidates may also receive public funds. The source of

the funds are primarily an appropriation and contributions by taxpayers from

tax refunds.

New Jersey

New Jersey's public financing law was enacted in the 1970s. It provides 2:1

matching funds for both the primary and general elections to candidates who

agree to spending limits. The system is funded by an income tax checkoff.

Rhode Island

Under Rhode Island law, candidates for statewide office who raise a threshold

amount of money and agree to spending limits are eligible for public matching

funds. Candidates are eligible for 2-to-1 public matching grants for

contributions of $500 or less and a 1-to-1 match for contributions in excess

of $500.

Vermont

In 1997, the Vermont legislature passed a public financing bill that provides

a fixed amount of public financing to candidates for governor and lieutenant

governor who raise a threshold number of small contributions and agree not to

raise any more private money. In a challenge to the U.S. Supreme Court's 1976

Buckley v. Valeo, the bill also imposes mandatory spending limits on all state

and local candidates. The primary source of funding is voluntary contributions

of taxpayer refunds; other sources are an appropriation and the revenue from

some fees and penalties.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin enacted its partial public financing system in the 1970s. It

provides matching funds to statewide and legislative candidates. The system is

funded by a tax checkoff. In recent years, the system has been damaged by a

decline in the amount of funds generated by the checkoff and growing spending

on independent expenditures and sham "issue ads."

updated

July 1999

A "tax add-on" gives taxpayers the option of reducing their tax refund

or increasing their tax payment in order to fund a public financing program.

State tax add-ons have not generated significant amounts of money.

A "tax check-off" allows taxpayers to earmark a small portion of their

taxes (usually $1 to $5) for distribution to candidates or political parties.

A check-off does not increase the individual taxpayers' tax liability.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()