|

|

|

...

SCHENDI ...

It is would seem an incomplete exercise to build an information

page about the inland area of the rainforests without speaking

also of Schendi. Indeed if the people of the interior can live

their whole life without ever going to Schendi, it is impossible

for visitors seeking the Ushindi or Ukungu areas or any area beyond

that to arrive there without first going through the harbor and

town of Schendi. Although many do not make the nuances between

Schendi harbor and the actual town of Schendi, a few pasangs separate

the two. Schendi itself is further south from the harbor and port,

it sits on a small peninsula called Schendi point. The town of

Schendi is home to approximately one million people most of whom

are black. The word Schendi is believed to be a phonetic corruption

of the inland word ushindi which was apparently used in long ago

years to designate the area where Schendi is located. The word

is also said to sound much like the inland word for -victory-.

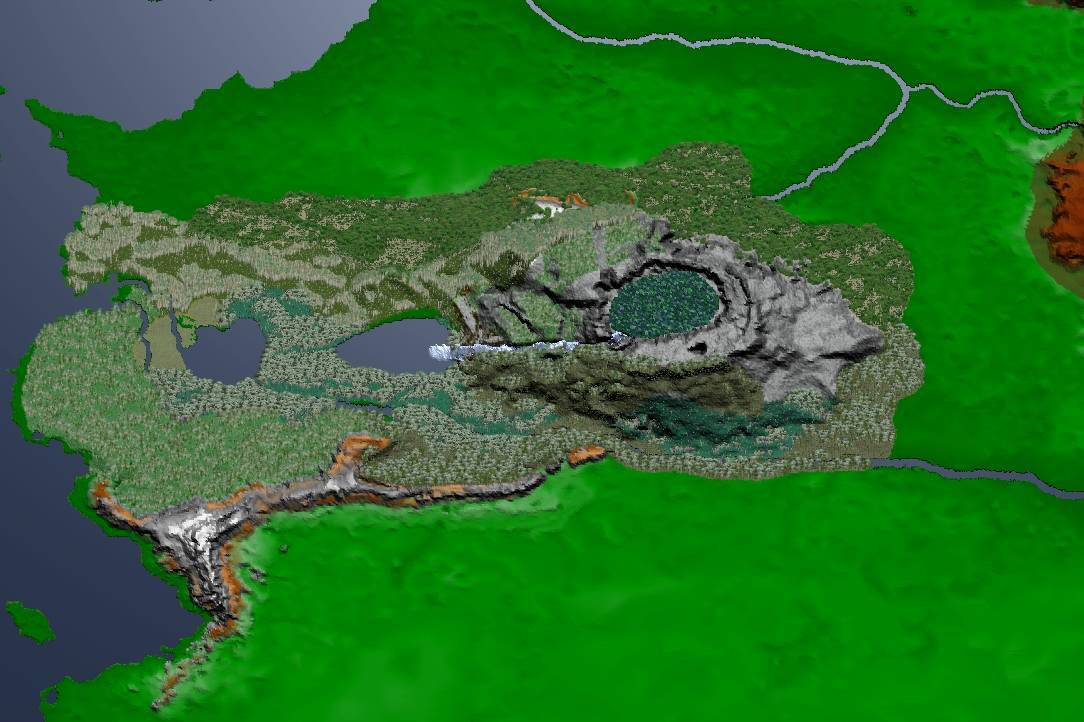

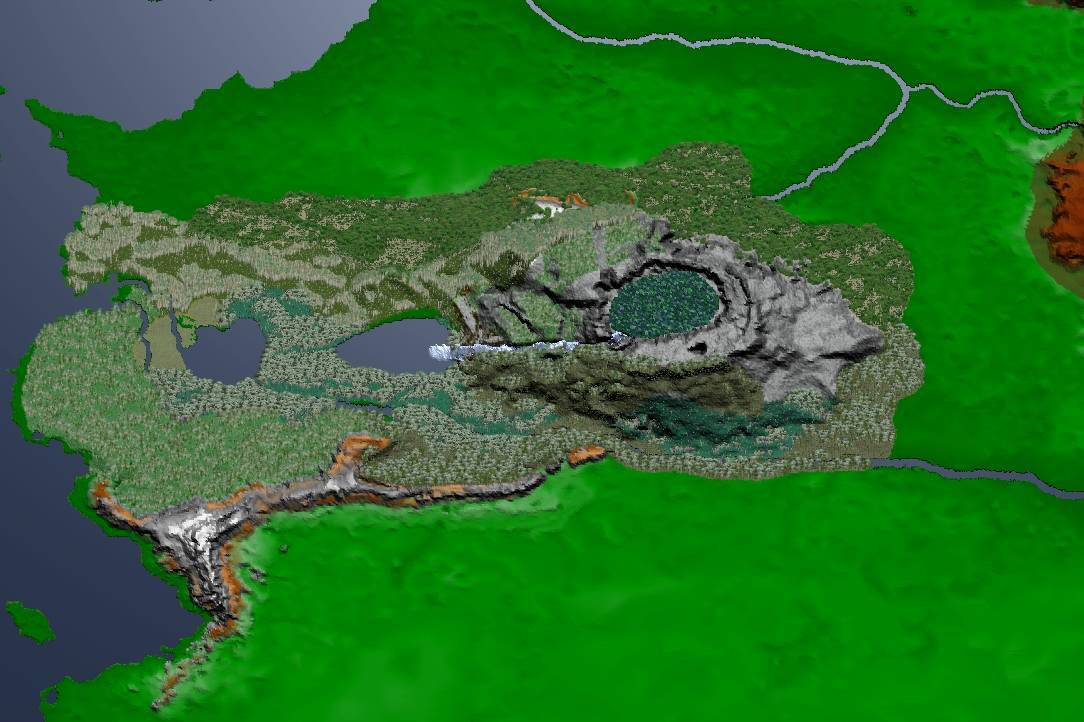

(((Another incredible Inukshuk map)))

Schendi

was an equatorial free port, well known on Gor. It is also

the home port of the League of Black Slavers.

---Ch1

Schendi

was a free port, administered by black merchants, members

of the caste of merchants. It was also the home port of

the League of Black Slavers but their predations were commonly

restricted to the high seas and coastal towns well north

and south of Schendi. Like most large-scale slaving operations

they had the good sense to spare their own environs.

---Ch1

The

word Schendi, as nearly as I can determine, has no obvious,

direct meaning in itself. It is generally speculated, however,

that it is a phonetic corruption of the inland word Ushindi,

which, long ago, was apparently used to refer to this general

area. In that sense, I suppose, one might think of Schendi,

though it has no real meaning of its own, as having an etiological

relationship to a word meaning 'Victory'. The Gorean word

for victory is "Nykus." which expression seems

clearly influenced by "Nike," or "Victory,"

in classical Greek.

---Ch6

I

now regarded again the brownish stains in the water. Still

we could not see land. Yet I knew that land must be nigh.

Already, though we were still perhaps thirty or forty pasangs

at sea, one could see clearly in the water the traces of

inland sediments. These would have been washed out to sea

from the Kamba and Nyoka rivers. These stains extend for

pasangs into Thassa. Closer to shore one could mark clearly

the traces of the Kamba to the north and the Nyoka to the

south, but, given our present position, we were in the fans

of these washes. The Kamba, as I may have mentioned, empties

directly into Thassa; the Nyoka, on the other hand, empties

into Schendi harbor, which is the harbor of the port of

Schendi, its waters only then moving thence to Thassa.

…

We had lain to after more closely approaching the port of

Schendi in the evening of the preceding day, the day in

which we had seen the fleet of the black slavers of Schendi.

We could see the shore now, with its sands and, behind the

sand, the dense, green vegetation, junglelike, broken by

occasional clearings for fields and villages. Schendi itself

lay farther to the south, about the outjutting of a small

peninsula, Point Schendi. The waters here were richly brown,

primarily from the outflowing of the Nyoka, emptying from

Lake Ushindi, some two hundred pasangs upriver.

---Ch6 |

On the edges of the equatorial

rainforests the major trade center that is Schendi is governed

as most free ports, by merchant law. Schendi hosts a huge harbor

of 8 pasangs wide and 2 or 3 deep where spices, metals, jewels

and other trade goods are shipped to the rest of Gor. Schendi

Harbor opens at its east end, onto the Nyoka River which flows

through it, from Lake Ushindi into Thassa.

Famous for its tapestries,

kailiauk horn products, precious metals and jewels, in particular

the carved sapphires which are unique to this area, Schendi exports

are as varied and exclusive as is the land and vegetation which

offers it. Many of the products harvested in the sub-equatorial

area are indigenous to no other land on Gor.

Many

goods pass in and out of Schendi, as would be the case in

any major port, such as precious metals, jewels, tapestries,

rugs, silks, horn and horn products, medicines, sugars and

salts, scrolls, papers, inks, lumber, stone, cloth, ointments,

perfumes, dried fruit, some dried fish, many root vegetables,

chains, craft tools, agricultural implements, such as hoe

heads and metal flail blades, wines and pagas, colorful

birds and slaves. Schendi's most significant exports are

doubtless spice and hides, with kailiauk horn and horn products

also being of great importance. One of her most delicious

exports is palm wine. One of her most famous and precious

exports are the small carved sapphires of Schendi. These

are generally a deep blue, but some are purple and others,

interestingly, white or yellow. They are usually carved

in the shape of tiny panthers, but sometimes other animals

are found as well, usually small animals or birds. Sometimes

however the stone is carved to resemble a tiny kailiauk

or kailiauk head. Slaves, interestingly, do not count as

one of the major products in Schendi, in spite of the fact

that the port is the headquarters of the League of Black

Slavers. The black slavers usually sell their catches nearer

the markets, both to the north and south. One of the major

markets, to which they generally arrange for the shipment

of girls overland, is the Sardar Fairs, in particular that

of En'Kara, which is the most extensive and finest. This

is not to say of course that Schendi does not have excellent

slave markets. It is a major Gorean port. The population

of Schendi is probably about a million people. The great

majority of these are black. Individuals of all races, however,

Schendi being a cosmopolitan port, frequent the city. Many

merchant houses, from distant cities, have outlets or agents

in Schendi. Similarly sailors, from hundreds of ships and

numerous distant ports, are almost always within the city.

The equatorial waters about Schendi, of course, are open

to shipping all year around. This is one reason for the

importance of the port.

---Explorers of Gor, 6:115 |

We

were still some seven or eight pasangs from the buoy lines.

I could see ships in the harbor.

We would come in with a buoy line on the port side. Ships,

too, would leave the harbor with the line of their port

side. This regulates traffic. In the open sea, similarly,

ships keep one another, where possible, on their port sides,

thus passing to starboard.

"What is the marking on the buoy line that will be

used by Ulan?" I asked Shoka, who stood near me, by

the girls, at the bow.

"Yellow and white stripes," he said. "That

will lead to the general merchant wharves. The warehouse

of Ulafi is near wharf eight."

"Do you rent wharfage?" I asked.

"Yes, from the merchant council," he said.

White and gold, incidentally, are the colors of the merchants.

Usually their robes are white, trimmed with gold. That the

buoy line was marked in yellow and white stripes was indicative

of the wharves toward which it led. I have never seen, incidentally,

gold paint on a buoy. It does not show up as well as enameled

yellow in the light of ships' lanterns.

I could see some forty or fifty sails in the harbor. There

must then have been a great many more ships in the harbor,

for most ships, naturally, take in their canvas when moored.

The ships under sail must, most of them, have been entering

or leaving the harbor. Most of the ships, of course, would

be small ships, coasting vessels and light galleys. Also,

of course, there were river ships in the harbor, used in

the traffic on the Nyoka.

I had not realized the harbor at Schendi was so large. It

must have been some eight pasangs wide and some two or three

pasangs in depth. At its eastern end, of course, at one

point, the Nyoka, channeled between stone embankments, about

two hundred yards apart, flows into it. The Nyoka, because

of the embankments, enters the harbor much more rapidly

than it normally flows. It is generally, like the Kamba,

a wide, leisurely river. Its width, however, about two pasangs

above Schendi, is constricted by the embankments. This is

to control the river and protect the port. A result, of

course, of the narrowing, the amount of water involved being

the same, is an increase in the velocity of the flow. In

moving upstream from Schendi there is a bypass, rather like

a lock system, which provides a calm road for shipping until

the Nyoka can be joined. This is commonly used only in moving

east or upstream from Schendi. The bypass, or "hook,"

as it is called, enters the Nyoka with rather than against

its current. One then brings one's boat about and, by wind

or oar, proceeds upstream.

The smell of spices, particularly cinnamon and cloves, was

now quite strong. We had smelled these even at sea. One

smell that I did not smell to a great degree was that of

fish. Many fish in these tropical waters are poisonous to

eat, a function of certain forms of seaweed on which they

feed. The seaweed is harmless to the fish but it contains

substances toxic to humans. The river fish on the other

hand, as far as I know, are generally wholesome for humans

to eat. Indeed, there are many villages along the Kamba

and Nyoka, and along the shores of Lake Ushindi, in which

fishing is the major source of livelihood. Not much of this

fish, however, is exported from Schendi. I could smell,

however, tanning fluids and dyes, from the shops and compounds

of leather workers. Much kailiauk leather is processed in

Schendi, brought to the port not only from inland but from

north and south, from collection points, along the coast.

I could also smell tars and resins, naval stores. Most perhaps,

I could now smell the jungles behind Schendi. This smell,

interestingly, does not carry as far out to sea as those

of the more pungent spices. It was a smell of vast greeneries,

steaming and damp, and of incredible flowers and immensities

of rotting vegetation.

---Ch6

As

we moved toward the wharves three ships passed us, moving

toward the open sea. There are more than forty merchant

wharves at Schendi, each one of which, extending into the

harbor, accommodates four ships to a side. The inmost wharves

tend to have lower numbers, on the starboard side of the

port, as one enters the harbor.

We could see men on the docks and on the out-jutting wharves.

Many seemed to recognize the Palms of Schendi and she was

well received. I had not realized that Schendi was as large

or busy a port as it was. Many of the wharves were crowded

and there were numerous ships moored at them. On the wharves

and in the warehouses, whose great doors were generally

open, I could see much merchandise. Most in evidence were

spice kegs and hide bales, but much else, too, could be

seen, cargos in the warehouses and on the wharves, some

waiting, some being actively carried about, being embarked

or disembarked. As the Palms of Schendi, her canvas now

taken in and the long yards swung parallel with the deck,

oars lifting and sweeping, moved past the wharves many men

stopped working, setting down their burdens, to wave us

good greetings. Men relish the sight of a fine ship. Too,

the two girls at the prow did not detract from the effect.

They hung as splendid ornaments, two slave beauties, dangling

over the brownish waters, from rings set in the ears of

a beast. We passed the high desks of two wharf praetors.

I saw, too, here and there, brief-tunicked, collared slave

girls; I saw, too, at one point a group of paga girls, chained

together, soliciting business for their master's tavern.

---Ch6 |

The vegetation and weather

of the Schendi region are referred to as -tropical- and can be

compared to our own rain forests in climate, alternating between

a semi-dry season and many rain seasons.

Schendi

does not, of course, experience a winter. Being somewhat

south of the equator it does have a dry season, which occurs

in the period of the southern hemisphere's winter. If it

were somewhat north of the equator, this dry season would

occur in the period of the northern hemisphere's winter.

The farmers about Schendi, as farmers in the equatorial

regions generally, do their main planting at the beginning

of the "dry season." From the point of view of

one accustomed to Gor's northern latitudes I am not altogether

happy with the geographer's concept of a "dry season."

It is not really dry but actually a season of less rain.

During the rains of the rainy season seeds could be torn

out of the ground and fields half washed away. The equatorial

farmer, incidentally, often moves his fields after two or

three seasons as the soil, depleted of many minerals and

nutriments by the centuries of terrible rains, is quickly

exhausted by his croppage. The soil of tropical areas, contrary

to popular understanding, is not one of great agricultural

fertility. Jungles, which usually spring up along rivers

or in the vicinity of river systems, can thrive in a soil

which would not nourish fields of food grains. The farmers

about Schendi are, in a sense, more gardeners than farmers.

When a field is exhausted the farmer clears a new area and

begins again. Villages move. This infertility of the soil

is a major reason why population concentrations have not

developed in the Gorean equatorial interior.

---Ch6 |

The language of Schendi

is Gorean unlike that of the interior. It is estimated that approximately

5 to 8 percent of the Schendi population is familiar with the

inland speech.

Like other Gorean cities,

Schendi has colors and symbols by which its people may be recognized

in multicultural crowds. The shackle and scimitar are mentioned

as the symbols of Schendi when describing a collar, it is not

further explained whether this is exclusive to the slaving industry,

to the trade business or a more universal symbol. The traditional

dress of Schendi includes a cap which is described as rather flat

and adorned with "the two golden tassels of Schendi".

Gorean,

incidentally, is spoken generally in Schendi.

---Ch6

All

eyes turned toward the back. A tall man stood there, lean

and black. He wore a closely woven seaman's aba, red, striped

with white, which fell from his shoulders; this was worn

over an ankle-length, white tobe, loosely sleeved, embroidered

with gold, with a golden sash. In the sash was thrust a

curved dagger. On his head he wore a cap on which were fixed

the two golden tassels of Schendi.

---Ch2

"I

have a collar here," said Ulafi, lifting a steel slave

collar. It was a shipping collar. It had five palms on it,

and the sign of Schendi, the shackle and scimitar. The girl

who wore it would be clearly identified as a portion of

Ulafi's cargo.

---Ch4 |

Homes and architecture

in the town of Schendi, are adapted to the heat, the humidity

and the presence of the habitual rather insistent types of insects

native to these jungles.

The most important business

of Schendi is of course trade, the port, the harbor and its many

many wharves and warehouses, and the production of kailiauk horn

and hide products.

I

could not see into the other room from where I stood, nor

did it obviously have windows. I backed into the dark street

and then, a few feet away, saw a low, sloping roof. Most

of the buildings of Schendi have wooden ventilator shafts

at the roof, which may be opened and closed. These are often

kept open that the hot air in the room, rising, may escape.

They can be closed by a rod from the floor, in the case

of rain or during the swarming seasons for various insects.

---Ch11

In

Schendi there were many leather workers, usually engaged

in the tooling of kailiauk hide, brought from the interior.

Such leather, with horn, was one of the major exports of

Schendi.

--Ch5

Do

you smell it?" asked Ulafi.

"Yes," I said. "It is cinnamon and cloves,

is it not?"

"Yes," said Ulafi, "and other spices, as

well."

The sun was bright, and there was a good wind astern. The

sails were full and the waters of Thassa streamed against

the strakes.

It was the fourth morning after the evening conversation

which Ulafi and I had had, concerning my putative caste

and the transaction in Schendi awaiting the arrival of the

blond-haired barbarian.

"How

far are we out of Schendi?" I asked.

"Fifty pasangs," said Ulafi.

We could not yet see land.

---Ch6 |

|

|

|