| Mayan

Civilization

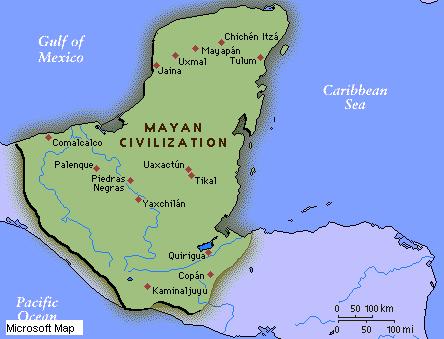

Maya, group of related Native American

nations of the Mayan linguistic stock, living in Mexico, in the states

of Veracruz, Yucatán, Campeche, Tabasco, and Chiapas, and also in

the greater part of Guatemala and in parts of Belize and Honduras. The

best-known people, the Maya proper, after whom the entire group is named,

occupy the Yucatán Peninsula. Among the other politically significant

peoples are the Huastec of northern Veracruz; the Tzental of Tabasco and

Chiapas; the Chol of Chiapas; the Quiché, Cakchiquel, Pokonchi,

and Pokomam of the Guatemalan highlands; and the Chortí of eastern

Guatemala and western Honduras. With the exception of the Huastec, these

peoples occupy contiguous territory. They were all part of a common civilization,

which in many respects achieved the most complex level of development among

the original inhabitants of the whole of the western hemisphere.

Agriculture formed the basis of the Mayan

economy in pre-Columbian times, maize being the principal crop. Cotton,

beans, squash, manioc (or Cassava), and cacao were also grown. The techniques

of spinning, dyeing, and weaving cotton were highly perfected. The Maya

domesticated the dog and the turkey but had no draught animals or wheeled

vehicles. They produced fine pottery, unequalled in the New World outside

of Peru. Cacao beans and copper bells were used as units of exchange. Copper

was also used for ornamental purposes, as were gold, silver, jade, shell,

and colourful feathers. Metal tools, however, were unknown. The Mayan peoples

were ruled by hereditary chiefs, descended from the male line, who delegated

authority over village communities to local chieftains. Land, held in common

by each village, was parcelled out by these chieftains to the separate

families.

back to top back to top

Architecture

Mayan culture produced a remarkable architecture,

of which great ruins remain at a large number of sites, including Palenque,

Uxmal, Mayapán, Copán, Tikal, Uaxactún, and Chichén

Itzá. These sites were vast centres for religious ceremonies. The

usual plan consisted of a number of pyramidal mounds, often surmounted

by temples or other buildings, and grouped around open plazas. The pyramids,

built in successive steps, were faced with cut stone blocks and generally

had a steep stairway built into one or more of their sides. The substructure

of the pyramids was usually made of earth and rubble, but sometimes mortared

blocks of stone were used. The most common type of construction consisted

of a core of rubble or broken limestone mixed with mortar, and then faced

with finished stones or stucco. Stone walls were also frequently laid without

mortar. Wood was used for door lintels and for sculpture. The arch was

not known, but its effect was approximated in roofing buildings by making

the upper layers of stone of two parallel walls approach each other in

successive projections until they met overhead. This system, requiring

very heavy walls, produced narrow interiors. Windows were rare and were

small and narrow. Interiors and exteriors were painted in bright colours.

Exteriors received special attention and were lavishly decorated with painted

sculpture, carved lintels, stucco mouldings, and stone mosaics. The decorations

generally were arranged in wide friezes contrasting with bands of plain

masonry. Commoners' dwellings probably resembled the adobe and palm-thatched

huts seen today among Mayan descendants.

Maya

Mayan civilization dominated southern

Mesoamerica in the second half of the first millennium AD. Although originating

in the Pre-Classic period, Mayan culture reached its artistic and intellectual

apex during the Late Classic phase, from about 600 to about 900. By the

time of the Spanish conquest it was in decline.

In the variety and quality of their architecture,

the Maya were unrivalled by any other pre-Columbian civilization. Classic

Mayan sites are primarily found in lowland tropical areas. With proportionally

more emphasis on ceremonial features, they appear to be less truly urban

than Teotihuacán. The majority of Mayan ruins are in Mexico; they

include Palenque, Yaxchilán, and Bonampak and, in the Yucatán

Peninsula, Chichén Itzá, Coba, Dzilbilchaltun, Edzna, Hochob,

Kabah, Labná, Sayil, Uxmal, and Xpuhil. Other major sites are Copán

in Honduras and, in Guatemala, Piedras Negras, Quirigua, and Tikal, the

largest of all Mayan ceremonial centres. Mayan architecture is characterized

by an exquisite sense of proportion and design and by structural refinement

and subtle detailing. The Maya used sculpture more extensively for architectural

decoration than any other pre-Columbian civilization. The corbel arch was

employed not only to vault interior spaces, but also to construct free-standing

arches. The Maya also built paved roadways connecting major religious and

administrative centres; these seem to have been used mostly for ceremonial

processions and to symbolize political links.

Mayan art is the most highly refined and

elegant of any pre-Columbian civilization. It has dignity and majesty,

and is exuberant and sensual, with lavish ornamentation.

Stelae with figurative carving and inscriptions

are the most characteristic examples of the monumental free-standing stone

sculpture of the Maya. The most elaborate examples are found at Copán,

where the softness of the stone made possible Baroque flamboyance of ornament.

Most major sites have well-developed traditions of architectural relief

panels in stone, and at Palenque stucco was effectively used for reliefs.

The Maya mastered all known pre-Columbian

art forms except metalworking. Although no Mayan textiles remain, their

character and decoration can be discerned from representations in painting,

figurines, and sculptures. Jade was skilfully carved, as were wood, bone,

and shell; in clay, however, the Maya excelled. Realistic figurines (especially

those from the island of Jaina) and polychrome pottery with mythological

or genre scenes (produced at Chama) are among the finest accomplishments

of pre-Columbian painted pottery.

Particularly fine examples of Mayan fresco

painting have been found at Bonampak, Palenque, and Tikal. The Maya also

produced codices, with hieroglyphic script. Of the surviving Mayan codices,

the Dresden Codex (Sachsische Landesbibliothek, Dresden, Germany) best

illustrates the Maya's descriptive and formally dynamic use of line.

"Pre-Columbian Art and Architecture," Microsoft(R)

Encarta(R) 98 Encyclopedia. (c) 1993-1997 Microsoft Corporation. All rights

reserved.

back to top back to top

Writings

The Mayan peoples developed a method of

hieroglyphic notation and recorded mythology, history, and rituals in inscriptions

carved and painted on stelae (stone slabs or pillars), on lintels and stairways,

and on other monumental remains. Records were also painted in hieroglyphs

and preserved in books of folded sheets of paper made from the fibres of

the maguey plant. Four examples of these codices have been preserved: the

Codex Dresdensis, now in Dresden; the Perez Codex, now in Paris; and the

Codex Tro and the Codex Cortesianus, both now in Madrid. The Codex Tro

and Codex Cortesianus comprise parts of a single original document, and

are commonly known under the joint name Codex Tro-Cortesianus. These books

were used as divinatory, almanacs containing topics such as agriculture,

weather, disease, hunting, and astronomy.

Codex Tro

One of the four preserved codices of Mayan hieroglyphs, the Codex

Tro dates from about the 14th century. These ornate pages from the Codex

form part of a prophetic calendar that predicts good and bad days. The

ancient Maya used paints made of natural pigments and paper made from the

fibres of maguey plants to record religious information and historical

events.

Codex Tro

One of the four preserved codices of Mayan hieroglyphs, the Codex

Tro dates from about the 14th century. These ornate pages from the Codex

form part of a prophetic calendar that predicts good and bad days. The

ancient Maya used paints made of natural pigments and paper made from the

fibres of maguey plants to record religious information and historical

events.

"Codex Tro," Microsoft(R) Encarta(R) 98 Encyclopedia.

(c) 1993-1997 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

back to top back to top

Calendar

and Religion

Chronology among the Maya was determined

by an elaborate calendar system. The year began when the sun crossed the

zenith on July 16 and consisted of 365 days; 364 of the days were grouped

into 28 weeks of 13 days each, the new year beginning on the 365th day.

In addition, 360 days of the year were divided into 18 months of 20 days

each. The series of weeks and the series of months both ran consecutively

and independently of each other; however, once every 260 days, that is,

the multiple of 13 and 20, the week and the month began on the same day.

The Mayan calendar, although highly complex, was the most accurate known

to human beings until the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in the

16th century.

The Mayan religion centred on the worship

of a large number of nature gods. Chac, a god of rain, was especially important

in popular ritual. Among the supreme deities were Kukulcan, a creator god

closely related to the Toltec and Aztec Quetzalcoatl, and Itzamna, a sky

god. A Mayan trait was their complete trust in the gods' control of certain

units of time and of all peoples' activities during those periods.

From the Pre-Columbian period to the present

day, the Maya people have inhabited an area centred on the Yucatán

Peninsula, western Mexico. Maya civilization reached its high point between

the 3rd and 10th centuries AD, but some Maya centres continued to flourish

up to the Spanish Conquest. The Maya kept written records in their hieroglyphic

script, which has still to be fully deciphered, and practised sophisticated

astronomy and mathematics. Almost the whole of Maya literature was destroyed

during the Conquest, so that the detailed nature of what was evidently

a highly complex mythology is difficult to reconstruct with any certainty.

The most important source for Maya mythology

is the Popol Vuh ("Book of Advice"), which was written in the Quiché

Maya dialect but in European script soon after the Conquest. The Popol

Vuh presents versions, sometimes possibly with a Christianized colouring,

of many myths and legends. One main element is an account of the Maya cosmogony,

in which the universe is conceived on three levels: an underworld; a middle,

earthly world; and a heavenly realm. The four corners of the world were

marked by different colours and supported by four Atlantean deities corresponding

to the colours and directions: Mulac-white-north; Kan-yellow-east; Cauac-red-south;

and Ix-black-west. The great Ceiba tree connected all three levels and

provided a route along which the souls of the dead and the gods could travel.

The gods made several attempts to create humans-out of mud, wood, and finally

maize.

The principal Maya deity was Itzamná

("Lizard House"), who was the supreme creator and Moon deity, and the patron

of writing and learning. He shares some characteristics with another major

deity, Kukulcán ("Feathered Snake Who Traverses the Waters"), who

was later adopted by the Aztec mythology as Quetzalcoatl. Itzamná's

consort was Ix Chel ("Lady Rainbow"), the goddess of childbirth, weaving,

and medicine. The Sun god, Ahau Kin, took the form of a jaguar to travel

through the underworld between sunset and sunrise.

The Popol Vuh also describes the exploits

of the heavenly twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who were challenged to a ball

game by the Lords of Xibalba (the underworld). Through bravery and cunning

the twins survived many trials before engaging the gods in a game. The

gods were impressed by the twins' ability to dismember then put themselves

back together again. When the gods allowed themselves to be cut up, however,

the twins left them in pieces, thus winning the contest. After this, Hunahpu

and Xbalanque were deified as the Sun and Moon.

"Native American Mythology," Microsoft(R)

Encarta(R) 98 Encyclopedia. (c) 1993-1997 Microsoft Corporation. All rights

reserved.

back to top back to top

Linguistic

Stock

Maya, (called also Yucatec), the language

of the Maya proper, is spoken by about 350,000 people in Yucatán,

Guatemala, and Belize. The other languages of the Mayan stock include the

language of the Huastec and several groups of closely affiliated languages.

back to top back to top

"Maya," Microsoft(R) Encarta(R) 98 Encyclopedia.

(c) 1993-1997 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

|