The Waterbury Watch Museum

- Home - History - Articles - Gallery - About Us - Credits - Contact - Resources

Articles \ "Clock and Watch Land"

Click on the thumbnails to view the larger image.

“The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine” July, 1882

”Clock and Watch Land”

The state of Connecticut faces the sun. That is, its surface slopes to the Sound. This divides the State into a series of parallel valleys. There is the Valley of the Connecticut, of soft and placed beauty; the hill-edged Housatonic, and the winding valley of the Naugatuck, or clock land. This, the smallest of the three valley’s is the home of some of the most unique industries of this industrious country. Here have sprung up towns famous for their workers in brass and metals, celebrated for their manufactories of clocks for all the world. Now come watches, a natural outgrowth of the clock-making industry. Here is Waterbury, where it is said that within a radius of twenty miles more clocks and watches are made than in any other place in the world. There is even a hint of the wooded hills of that other watch country – Switzerland. There a hardy and industrious people tend their poor, rough farms in the summer, and make watches by hand in winter. Here is the same rough and broken country, a poor land for farmers, where the people make watches by the gross. For the tourist, the Naugatuck is well worth a visit. There are wooded hills, wild glens, and the noisy river, good hotels and lively towns, every one a shop. Here are the skilled workers in brass, the rubber men, and the clock and watch men. Their land may be poor, but their hands and brains have made them rich, in spite of the forbidding rocks and stony pastures.

The school geographies of a quarter of a century ago used to speak of Trade and Commerce in a flattering way, intended to convey the idea that the exportation of hymn-books and New England rum to the benighted inhabitants of the South Seas was a highly commendable work. “Commerce introduced civilization among the heathen; trade was a Great Moral benefit to all the nations.” The geographers have grown wiser, yet business, meals, a comfortable house, and a good suit of clothes are aids to virtue, then the factory, the shop, and the mill have other missions besides paying dividends.

Fifty years ago a clock was a house-hold heirloom, only to be bought with much money or inherited from rich parents. To-day, no tenement so poor it has not its mantel clock from the Naugatuck. Fifty years ago only the rich man could wear a watch. To-day, the laboring man need not importune the passing stranger to know “if it is noon yet?” for he has a good watch in his pocket. Perhaps it is not fair to call a watch a luxury. This generation lives “on time.” The railroad has become the monitor of the people. If it is, you are sure to be left out of modern business life. A timepiece of some sort is a positive necessity. Only a jeweled watch, timed to split the seconds, is a luxury; a good, serviceable, reliable watch is a necessity – a first requisite in all business and social life.

The manufacturers of the Naugatuck Valley early saw this want and undertook to meet it by making cheap clocks. Not merely a “cheap John” trickery, but real, steady-going clocks, of honest face and well-regulated character.

After that came the American watches. If machinery could be used to make a clock, then it might be trained to finer and higher work. The Waltham and Elgin watches made it possible for people of moderate means to carry the time in their pockets. The success of American machine-made watches has revolutionized the business of making watches the world over. With all this, there was still a wide field unoccupied. There were still multitudes so poor they could not buy a watch. Then it was that it occurred to some of these long-sighted manufacturers of the Naugatuck Valley that, if a good reliable watch could be made and sold for about three dollars, that it would pay. Now, a thing pays because it meets a human want. Was there a want? Did the people really wish a cheap watch? The question did not require much discussion. A watch for three dollars would meet a want – it would pay.

There are two ways in which a want is met. The thing is discovered or it is invented. When it was recognized that there was a demand for a three-dollar watch, the usual course of invention was reversed. The watch was not discovered, nor was it invented as a whole, or as a single idea that might be made into a practical machine. The firs thing that was done was to find a man to take an order for the watch. Naturally enough the watch making profession was looked to for the coming man. A watchmaker or watch repairer would at least know the difficulties of filling such an order. He would know, in a general way, what it had been done, or, what was more important, what could not be done.

The commission was a strange one. Wanted – a man who can make a watch that should have a less number of parts than any watch ever made. Anybody can make a watch if you place no limit on the material and labor. The English watchmaker can make a magnificent watch if you let him put in any number of parts and you are not particular about the cost. The Waltham and Elgin people can make a first-class watch with only one hundred and sixty parts, and do most of the work by machinery. The price will be far more reasonable, but it will, at best, be many times three dollars.

To understand this difficult problem you must observe that a watch is simply a means of storing energy. You consume a certain amount of food. It is potential energy, though the poets call it the “staff of life,” and that sort of thing. In an hour or more you are able to realize the energy as actual work performed by your hand or arm. You spend a trifle of this energy in winding up a watch. The watch spring has now become stored with energy that directly came from good beef, and originally from the sun that built up the grass the ox fed upon.

If the spring were free to unwind it would give one vigorous twist, and spend the energy in an instant and to no purpose. By tying the spring to a train of wheels it is possible to make the spring spend its energy slowly in the work of turning the hands of the watch. It only requires some system of regulation to make the energy you put into the spring in one minute to extend itself over twenty-four hours. It is wound up quickly. It must run down slowly. The Englishman and the Switzer can do this well, if we give them money enough. Who can do it cheaper than all? Clearly the American! This narrowed it to New England.

At the Centennial Exhibition there was shown the largest steam engine in the world. One day there came a man to the main building with a new steam engine in his vest pocket. For a house to shelter the motor he used a tailor’s thimble. It had a boiler, a cylinder, valves, a governor, crank, piston, and shaft, and it would work. Three drops of water filled the boiler, and when steam was up it started off in quite the correct steam-motor style, and stood at work near the greatest engine in the world – its brother, and yet the smallest. The man who could, with a common watch repairer’s tools, design and construct such a machine was the man to make the coming watch. This was Mr. D.A.A. Buck, at that time living in Worcester, Mass. He took the commission and – failed. Then it seemed as if the whole idea was past doing. A three-dollar watch that was not a toy could not be made. It is not in your true Yankee to give up. Within a year Mr. Buck had invented, or thought out, and constructed another watch.

It had been found! Here was a real practical timepiece, a regular watch, with fewer parts than had ever been seen. The watch had been constructed by hand, every part cut out with ordinary tools. Could it be made by machinery on a large commercial scale? That was the question for the Naugatuck. In this land of cheap clocks could be found, if anywhere, the men to invent the machinery and make it too, the business men who could see the matter in its commercial aspects, and here was capital in exhaustless abundance. The histories of commercial enterprises are often as interesting as the histories of men and nations, there are ups and downs, failures and successes, happy discoveries and discouraging delays when it seems as if inanimate things are really totally depraved.

This first hand-made watch was shown to Mr. Charles Benedict, of the Benedict and Burnham Manufacturing Company, of Waterbury. This company owns the largest brass making plant in the world. They had a large force of skilled workmen and many fine tools for working in brass. The new watch was carefully examined by Mr. Benedict. It was tested in every imaginable way, and it stood the tests. Mr. Benedict at once saw a gigantic business in the new watch. No need to make a second. The question was now how to make a million just like it. He arranged at once that the work of making watches should begin in their establishment. It was thought that with the tools already owned by his company, and by the construction of others, that the business of making watches could be started in about six months. It took nearly two years, and over two hundred thousand dollars, to merely make the tools and machinery. The three rooms first taken at the works of the Benedict and Burnham Company soon proved too small. This led to the formation of a stock company and the building of a factory. The company was incorporated under the style of the Waterbury Watch Company, with Mr. Charles Benedict for its first president.

The Company became the owner of the patents, for this watch, simple as it is, contains more novel features that are fully protected by patents, both in this country and in most countries where patents can be obtained.

The factory was designed by Mr. H. W. Hartwell, of Boston, the architect of the celebrated watch factories at Waltham, Mass, and Elgin, Ill. Though this was to be a low-priced watch, it did not follow that the actual plant where it was to be made was to be cheap. The factory was to be the best – as good as would be required to make any watch. So it happened that when the building was finished and furnished complete it was found that nearly half a million of dollars had been expended, and all this to make a watch that could be sold for less than four dollars, or, better still, to make a million watches, not one of which should cost over three dollars and fifty cents retail.

About May, 1881, manufacturing was commenced in the new factory. From that time to this the Waterbury watch, as it is now called, has been steadily produced at the rate of six hundred completed watches in a day, or about one a minute.

What is the outcome of all this great expenditure of time, thought, labor, and money? A good, serviceable, and reliable watch that may be bought anywhere in the United States for just three dollars and fifty cents. This is the Waterbury Watch. There is only one style, and all are exactly alike, except that a few thousand have been made in colored celluloid cases. The cases of the standard style are of nickel-silver. Through the open dial can be seen nearly all the moving parts, which give the watch a mechanical interest, aside from its beauty and usefulness.

The Waterbury is a stem winder. The moment you attempt to wind it up, you find it winds steadily and evenly, but the winding requires a long time. It takes two full minutes to wind the watch, or half that if you have the wit to wind it night and morning. If you are one of those clever people who teach themselves to do mechanically what others do by force of will, you can give the stem a few turns every time you look at the watch. This keeps the watch well wound and relieves the mind of care in the matter. Light-minded persons who have looked at a Waterbury, without taking the trouble to own and use one, have smiled in a superior way at the long winding required. What would you have? You can’t have everything for three dollars and a half, and if you examine the Waterbury in a scientific spirit, you will find there is a good reason for the whole thing.

The one thing in a watch most liable to break is the main spring. Now, in a cheap watch, the spring must not break. If the spring has to be replaced every little while where is the cheapness? Why, in some said to be cheap watches, the cost of a new spring will be more than the whole value of the watch. The Waterbury does not belong to that class.

On opening the back of the Waterbury, which, by the way, you should never attempt to do yourself, may be seen a steel spring, coiled upon a brass plate that nearly fills the entire back of the case. This plate has a geared edge, and upon the stem, which projects through the case, is a smaller gear fitting into this, so that in winding up the spring the entire plate bearing the spring is made to revolve. Taking up this plate, you find all the works under it are free to revolve upon an axis at the center of the watch, so that all the works turn entirely around once every hour. On winding up the watch, the plate turns around, thus coiling up the spring. There is no possible danger of over-winding or breaking the spring in that way; for, when the spring is wound up, a strong stop-motion or ratchet catches in the case itself, and holds everything firm. You may twist off the stem, but you can not break the spring. Moreover, the spring is very thin, and, therefore, less liable to break under rough usage, and it actually requires less power to wind the watch than in any watch yet made.

The watch is now wound up. The energy stored in the spring is now realized as work, and a part of this work is to turn the entire interior machinery of the watch around in the case once every hour. The minute hand on the face of the watch turns with the works, and thus by this simple device all the machinery needed in an ordinary watch to turn the minute hand is got rid of.

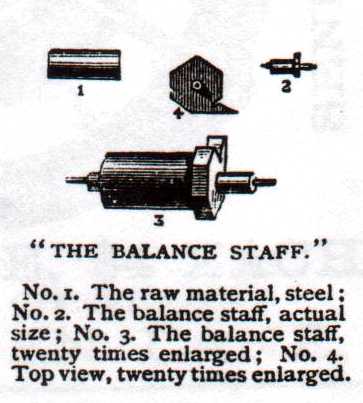

By these two devices is the cost of the watch reduced – the long spring and the revolving motion of all the parts about the center of the case. The next step, and the last, is to put in the simple machinery that will turn the hour hand and control the movements of the whole train of wheels. This consists of only three wheels and a hair spring and balance wheel. This is the whole story! A spring, a revolving wheel-work and balance wheel-work, and a train of three wheels. This is the last simplicity! – the very end. You can not have less than these, and have a watch. Taking every part – screws, pinions, wheels, case, springs, and fittings – together there are only fifty-eight parts in all, and one less than this is not possible, if the watch is to go and keep good time.

There is another point in connection with the Waterbury. If all the works revolved around the center of the case every hour, it is evident that the bearings of all the wheels, those parts that wear the most, will be continually shifting their position. The pressure or weight upon the bearings will be continually changed – if there is any wear, it will be distributed equally. There will be no need of jewels on which to rest the moving parts, for the weight is equal at every point. Here is another method of reducing the cost. Besides this, such a watch will keep good time in all position, wether lying down or standing upright, or up side down. Whatever its position, the wear will be even, because the watch itself is continually adjusting itself to new positions.

All the parts of the watch are interchangeable. If you had a pint of wheels, a pint of pinions, or fifty-eight quarts or pints of each of the parts, you could put them together and produce watches at wholesale, and every watch would be a success at once.

If a number of men are set to work to add figures, or to do any work requiring constant repetition of one thing, it will be found that there will always be a certain fixed proportion of mistakes or errors. More curios still, each man will have his own fixed ratio of mistakes. This is known as personal equation. If, as in Switzerland, a hundred people make different parts of watches, one man making screws, another pinions, another wheels, and so on, there will be at all times a fixed proportion of bad work. The wheels may be, apparently, according to patter and, apparently, exactly alike. But take a quantity of these works and try to put them together, you will find that they will not work at all. The personal equations of the different makers will upset everything. A hand-made watch that will go together perfectly and start right off without adjusting, filing, and fitting is a physical impossibility. Take twenty Swiss watches apart, and after mixing the parts together you will find that you have spoiled twenty old watches without being able to make a new one. The hand-made watch is a complete organism, very perfect, no doubt, but that sort of perfection costs a deal of money. A watch made entirely by hand would cost as much as a cottage by the sea-shore, or a small yacht, and would take about as long to build. The Waterbury goes together without fitting, or with so little that it does not materially add to the cost. Machines have no personal equation. This is one great secret of the cheapness of the Waterbury Watch.

The factory erected by the Waterbury Watch Company is admirably located in the center of a large plot of level ground, ornamented with lawns and shade trees and in convenient reach of the center of the city. The building is of brick, and consists of three parts: a square central building four stories high, a long wing or extension in the rear three stories high, and a one-story annex or smaller wing. This covers the present plant, but there is ample space for two more wings which the company contemplate building. In the basement of the central building is the spring department and the pattern shop, that is well supplied with tools of the latest and most improved design. This shop is fully occupied in making and repairing the fine machinery used in the actual work of making watches. In all this work the metric system is used, and the best metric gauges are used throughout the factory. These gauges will measure thousandths of a centimeter. A special set of standard gauges are always kept on hand, and by these all the gauges used are frequently tested. There is nothing like testing your tests in such an art as this.

The next floor of the wing is devoted to the case department. On the same floor of the main building are the offices of the company. Above the offices is the material room, where supplies of all the different parts of the watches are kept in glass jars on shelves or in drawers and cases. There is at all times in this room enough parts to make fifty thousand watches, so that if any part of the factory should be disabled the making of watches could still proceed while repairs were being made. On the same floor is the designing room occupied by Mr. Buck, who made the original watch, and rooms of the model maker and the mechanical super-intendent , the draughtsman and the company’s horological library.

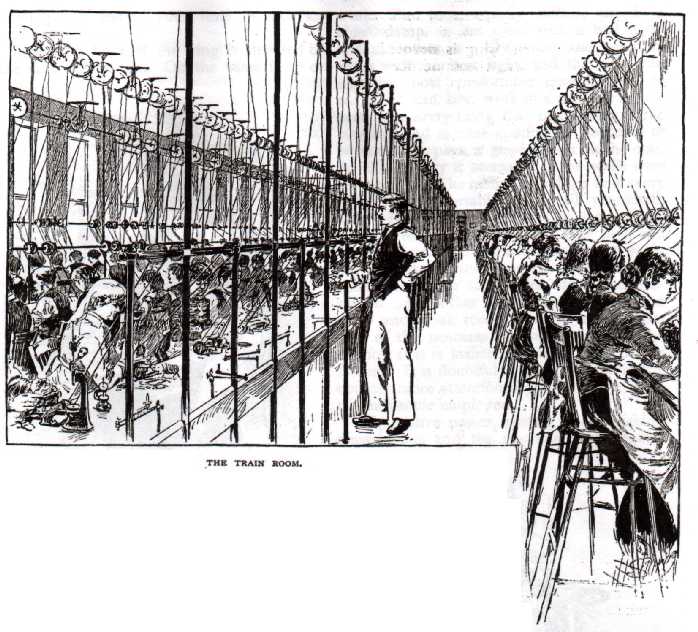

On the top floor of the wing is the train room, where all parts of the wheel work or train system are made and finished. On the top floor of the main building is the assembly or finishing department. This is a large and lofty room and acknowledged by experts to be the finest watch assembly room in the world. It is here the parts are assembled and the watches are put together, tested, regulated, and made ready for sale.

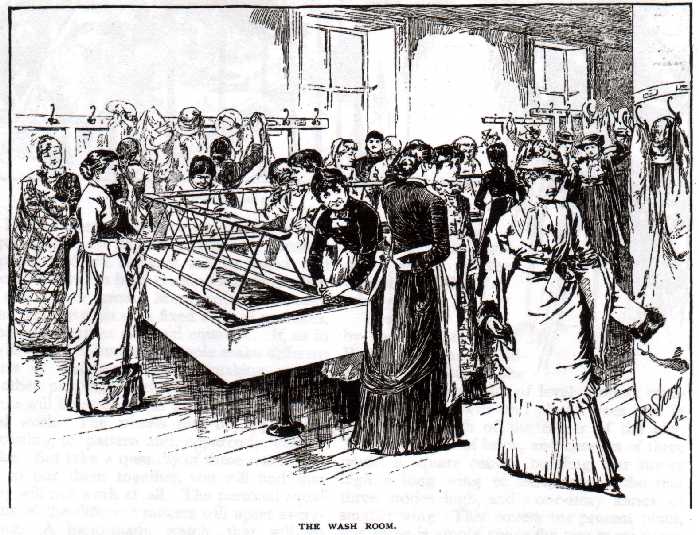

The first requisites of a watch factory are neatness and abundance of light. It is now recognized that no man can do his best work unless he is physically comfortable. Excess of heat or cold, a poor light, and, more than all, bad air, are positive hindrances to good work. Two men, equally skilled, one in a close, damp, or hot room with a bad light, and the other in a dry, sweet, and healthful room with the best light, and the mad who has the most comfortable quarters will do the most and best work in a day. It is now seen that every thing that contributes to the physical and mental comfort of the workmen or workwomen pars a good return on the cost. In this factory it seems as if the walls were all windows. The ceilings are high and every room is comfortable and well ventilated. Everywhere there is the utmost neatness, no dust, no smoke, no bad air. Every man and woman is provided with fresh water for the face and for drinking. The illustration on another page shows one of the wash and cloak rooms, and gives a suggestion of the neatness, to say nothing of the comfort that is insisted on in all parts of the factory. It is doubtful if in any works in the country more attention is paid to the comfort of the people employed.

The motive power, plating and polishing departments and the machine shop require no particular mention. Each is provided with the best tools and, together, they give employment to sixty men. In the spring-making department we come to the first work of special interest. When the company began to make watches it was thought that a common watch-spring would serve the purpose. At the very outset difficulties were encountered. The spring must be a good one, of the best material and workmanship. The difficulty was to get good steel. Every market in the world was searched for steel, and, after trying all brands it was found that American cold-rolled steel from Pittsburgh, PA, was the only thing that would meet the exacting demands of this watch. At first the springs were bought, but it was soon found that to get just the right thing it was better to make the springs in the factory from the mill. It may here be remarked in passing that not only the steel but every part is produced in this country. The Waterbury is purely an American watch. The ribbons of steel that come from Pittsburgh are wonderful for their uniformity of gauge. They seldom vary more than one-thousandth of a centimeter in thickness in any part. Each ribbon is slit by machinery into narrow strips nine feet long, and these are then coiled into flat bundles and made ready for hardening. After hardening they are then rubbed down with emery till they are everywhere exactly six one-thousandths of a centimeter thick. After the rubbing down, as shown in the accompanying picture of the department, comes the blueing or tempering and the winding into coils for the watch.

The keystone of this whole art of watchmaking, as carried on in this country, is the train room. In this factory this department occupies the entire top floor of the wing. It is lofty, light, and well ventilated, and is regarded as the finest train room in the United States. The interior is happily shown by the accompanying illustration. It is here the various wheels and pinions forming the train are made in whole or in part. The machinery used for this work is most delicate and the most costly in the world. Nearly all the machines are watched and tended by girls. We will not say guided, for they are almost every one automatic in their action and will do everything but think.

We may take for example the automatic wheel-cutter. This machine, that is hardly eighteen inches square, will space off, count and cut teeth of fifty wheels at one time. Moreover, it will cut just so many teeth, no more and no less, and every tooth and every wheel will be exactly alike, and when the work is done it will stop. The attendant picks up fifty brass blanks, just as they come from the stamping department, and slips them on to a mandrel. She then sets the mandrel in the machine, covers it over with a metal shield to keep out the dust, gives a drop of oil here and there and starts the machine. It goes soberly on with the work, feeding the blank wheels up to the cutting tool and turning out in a few minutes fifty finished wheels ready to go into fifty finished watches. Meanwhile, the girl is preparing fifty more wheels for a second machine and by the time that machine is ready the first has stopped and is ready to be loaded again.

Here is a girl at work with a tiny lathe, called the automatic staff or pivot lathe. This minute part of the watch is of steel only fifty-three one hundredths of a centimeter thick, and the part cut in the machine is only twenty-two thousandths of a centimeter in diameter, yet on this machine the girl can perform three thousand eight hundred operations in a single day. It is only one minute step in making the staff, for, small as it is, it goes through twenty-seven different hands before it is finished. The illustration gives a good idea of the machine, the work, and the girl.

This is only one machine, but is a fair sample of them all. Extreme fineness, perfection of finish, and accuracy of adjustment are the points sought for in their construction. Every part of the room is filled with tools of wonderful ingenuity. This may be a cheap watch, but, as far as the factory is concerned, the tools must be the same as in any first-class watch factory. The Waterbury may have few parts, but it takes five hundred operations to make a single watch. The only difference between this watch and the most costly is the fewer parts, less material, and different arrangement of the parts. Accurate records are kept by a simple system of bookkeeping of every block of metal given out and every piece of finished work brought back. Each workman and woman must return just as many as he receives, including the broken or injured pieces, or make up the loss. When the work is done the finished parts go to the material-room to be stored in quantities till wanted for the assembly department.

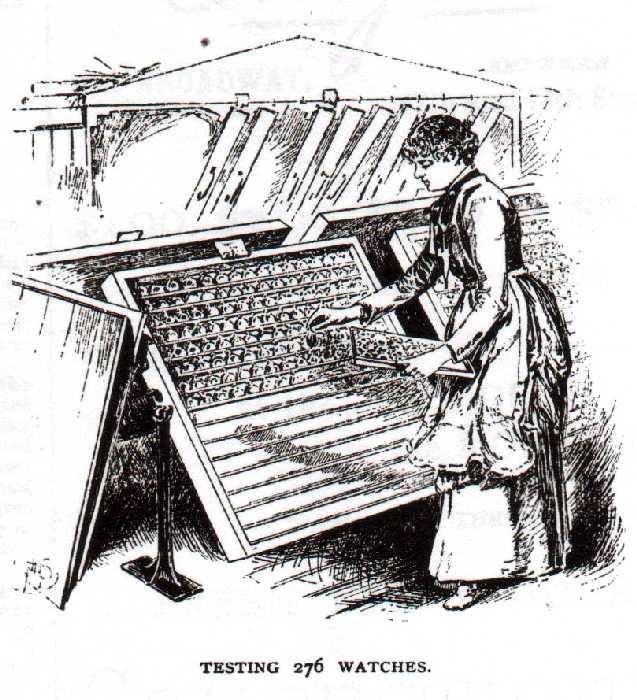

The finishing, the final putting together of the parts, and making the watches is all done in the spacious room at the top of the building. Here are the fitters who take the different parts of the train work and the springs and put them together. Here is the grand test of the whole art. If these quarts and pints of parts will not go together without difficulty the whole factory is a failure, and a cheap watch is an impossibility. They do so go together, not absolutely without any fitting whatever, but so nearly so that it may be practically said that watches can be made every time without mistake and every watch will be a good one. The works are then put in the case and we have a finished watch. It can be wound up and it will go fairly well at once. However, this is not enough. They must be regulated and must be thoroughly tested before they leave the factory. For this purpose large trays, each holding 276 watches, are prepared. The watches are wound up and put in the tray and left to run for twenty-five hours. These trays are supported on pivots that enable them to swing or turn completely over. First the tray filled with watches all in motion is placed in one position, say upright. It rests there for a day and an hour. Then the watches are all wound again and the tray is turned up-side-down. At the end of the next twenty-five hours the tray is turned at an angle of forty-five degrees. Six days pass and in that time every watch has been for a day in a different position. If any one or more watches stop they are taken out and sent to the inspectors to be examined to see what is the matter. If the watch stands the six days’ test it is regarded as a good watch, ready for sale, and it goes to New-York and a market. The accompanying picture shows the manner of testing the watches in the assembly room.

Six hundred watches a day is a good many. You would imagine the whole country supplied by this time. By no means. This is the farmer’s watch, the miner’s watch, the school-girl’s watch. The majority of these never owned a watch before. At the jeweler’s it may be found neatly packed in a satin-lined box, finished and ready for immediate use. With it comes a book of advice concerning the watch, and all at a price that puts a good time-piece in every pocket in the land. They luxuries of the rich have come to the poor. Perhaps after all that is not it. The necessities of the times have made watches essential to business, in school, at home, and in society. The Waterbury watch is the people’s time-piece, at once a trusty friend and monitor.