| |

|

Story and photos by Lawrence R. Heaney,

Danilo S. Balete,

Eric A. Rickart,

Ma. Josefa Veluz,

and Joel Sarmiento

The three peaks of Mt. Banahaw rise high above the Laguna and Quezon provinces, a familiar sight to vast numbers of people. Steeped in history, the mountain has a prominent place in the hearts and minds of the Southern Tagalog region. We recently discovered that this familiar mountain is bale to surprise, even amaze, in ways that we could never have anticipated.

We had gone to the mountain, most of which is within Mt. Banahaw-San Cristobal National Park, to conduct a survey of its small mammals, since the animals of this area are surprisingly poorly known.

We knew beforehand that Luzon Island has one of the world's greatest concentrations of unique mammal species, and that tall mountains and mountain ranges in Luzon often support species that live i nowhere else, separated by broad lowland plains.

For that reason, we predicted that Mt. Banahaw could have several previously unknown species of small mammals, but that they would be closely related to other species elsewhere in Luzon.We also went to Mt. Banahaw with the expectation of seeing wide- i spread destruction of the lowland forest by logging and kaingin, as is the case in far too many places in the Philippines.

But the prospects of finding previously unknown species outweighed the problems we expected, so on April 28, 2004, we left the Haribon office in Quezon City with our camping and research gear. The next day, we hired porters from among the local farming community in Barangay Lalo, Tayabas Municipality in Quezon Province, and hiked to our first campsite at about 1500 meters elevation on the mountain.

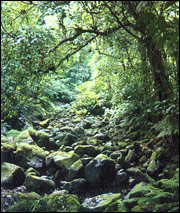

For the next two weeks, we sought the small mammals that live on the ground and in the trees in the montane forest that cloaks the mountain at that elevation, and still higher at 1750 meters, where the steep terrain and cold, wet weather have caused the forest to be left mostly untouched. Much to our delight, we found forest mice (the genus Apomys) to be abundant, with one large, short-tailed species on the ground, and one long-tailed species in the trees. The large one seems to be somewhat different from those we have studied elsewhere, and we will study our voucher specimens carefully during the coming year to determine if they represent a distinct I species. We also caught quite a few of the fruit-eating forest rats of i the genus Bullimus, and found them to be smaller and darker than those anywhere else, and so perhaps also representing a species new to science.

We were especially excited and happy to catch a Rhynchomys, which

feeds almost exclusively on earthworms. With their extremely

elongate snouts and tiny mouths and teeth, they are unmistakable,

but this one had several features that are different from the two

known species from Mt. Isarog in Bicol (R. isarogensis) and from the

Central Cordillera (R. soricoides).

And so, on May 12, we happily

left our high mountain camp to spend the last few days in remnant

lowland forest at 600 meters elevation. With help from our new

friends in the farming community, we hiked down the mountain with

our gear, and temporarily set up camp at a small community building

that was still under construction.

| |

|

Our first surprise came as we explored the nearby area. Rather than rampant logging and increasing areas of kaingin, we found the adjacent watershed to be clothed in naturally regenerating secondary lowland forest; instead of degradation, we saw evidence of years of careful reforestation with native trees and vigorous volunteer growth of understory plants, vines, and epiphytes. There were dozens of small vegetable garden plots, but they were carefully laid out and densely planted to avoid erosion, and each was surrounded by a buffer zone of thick natural vegetation.

We learned that the farmers were members of a barangay that recognized that their rice fields further down the mountain required the mountain's clear, abundant water for irrigation, and since their livelihoods depend on rice, they place great emphasis on careful management of the watershed. They restrict further clearing for garden plots, and they very carefully limit burning. They have also all but eliminated logging, and they forbid mining or treasure hunting. All of this is done in cooperation with the Protected Areas and Management Board of the Mt. Banahaw National Park, which deserves credit for their ongoing efforts to protect the park, but it seemed evident to us that it was the local community that provided the direction and determination to stabilize their environment. Lowland forest is now perhaps the rarest habitat on Luzon, and so even this relatively small area of recovering forest represents an important reason for hope for the future.

Truly delighted with this very unusual and heartening situation, we set about exploring the secondary forest of the vicinity. We quickly learned that the destructive rodent pests of Philippine croplands were restricted to the community building and the garden plots; in the regenerating forest were only the species native to the Philippines that typically do no harm to human activities, and that indeed usually avoid humans and their disturbance very actively, including Apomys and Bullimus. But in the process of our sampling came our second surprise.

On the next to the last day of our stay in camp, one of our team was checking a line of traps he had set well above the ground, up on horizontal branches and on the tops of some large lianas that snaked up into the canopy. As he approached one trap he saw a tiny bit of orange fur—and as he came closer, he realized that it was a complete animal. He carefully removed it from the trap, and immediately headed back to camp, knowing that this was one of those grand and glorious moments that all biologists dream about.

Within the next several months, we will gradually compare the mouse to other known species, and we will eventually learn how it fits into the broad picture of the evolution and ecology of mammalian biodiversity that we have been gradually building. But as of the day of this writing, May 21, just four days after capturing the mouse, we know that it is utterly unlike any species of mammal ever before seen by a biologist in Luzon. It is tiny, only 15 grams.