The great mountain of the Garhwal Himalaya, is Nanda Devi, with it's twin summits peaking at a little over 25,645 feet. The massif stands alone, encircled in a vast ring of lesser peaks seventy miles in circumference. In this ring are no fewer than nineteen peaks over twenty one thousand feet and no known break below 17,000 feet, except in the west, up the incredible gorge of the Rishi Ganga. The first successful entry into the inner "sanctuary" of Nanda Devi was made up this gorge in 1934, after years of failed attempts. Eric Shipton and H.W Tilman entered the pages of exploration history, when they along with their Sherpa porters, became the first men to set foot in the Nanda Devi sanctuary.

The main axis of the range continues north through Dunagiri - 23184 feet, onto the Chaukhamba group, smack atop the

headwaters of all the main source rivers of the Ganga. Chaukhamba, meaning four pillars, lies as a 23500 foot high mooring

post for the Great Gangotri glacier to the west, the Bhagirathi glacier to the north, and the glacier systems of Bhagat Kharak

and Satopanth to the east. The magnificient thirty kilometer long ridge has four peaks in the 7,000 meter region.

The main axis of the range continues north through Dunagiri - 23184 feet, onto the Chaukhamba group, smack atop the

headwaters of all the main source rivers of the Ganga. Chaukhamba, meaning four pillars, lies as a 23500 foot high mooring

post for the Great Gangotri glacier to the west, the Bhagirathi glacier to the north, and the glacier systems of Bhagat Kharak

and Satopanth to the east. The magnificient thirty kilometer long ridge has four peaks in the 7,000 meter region.

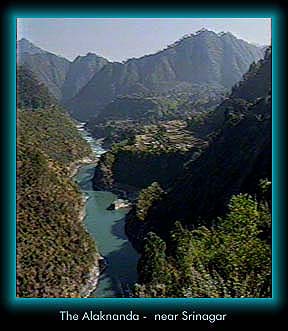

Just as the Great Gangotri glacier gives rise to the Bhagirathi, so does the Bhagat Kharak and Satopanth group give birth

to the Alaknanda, the other main source river of the holy Ganga.

Just as the Great Gangotri glacier gives rise to the Bhagirathi, so does the Bhagat Kharak and Satopanth group give birth

to the Alaknanda, the other main source river of the holy Ganga.

On the banks of the Alaknanda, barely 24 kilometers from the source, is situated the holy town of Badrinath, at an altitude of 11,000 feet.

Badrinath, overlooked by Neelkantha is the site where Lord Vishnu meditated for thousands of years eating just

the Badri grass found here. Sometime in the 8th century, the great reformer Adi Sankara came here and decreed

it, along with the other great Dhams of Uttarakhand, to be a meeting place of Heaven and Earth and consequently a site

of pilgrimage.

Over the centuries as Badrinath grew in fame and repute, the number of pilgrims gradually

increased. The journey was so dangerous that many did'nt make it. The rigours were

such that one bade a final farewell to everyone upon leaving home. The present temple

was built by the Raja of Tehri in the 15th century and the town grew gradually in the

intervening centuries. That is till the mid nineteen sixties and the coming of the motor

road. Pilgrim traffic has been going up in a geometric progression ever since and hundreds of thousands now

pay obesiance at Badrinath, every year.

Over the centuries as Badrinath grew in fame and repute, the number of pilgrims gradually

increased. The journey was so dangerous that many did'nt make it. The rigours were

such that one bade a final farewell to everyone upon leaving home. The present temple

was built by the Raja of Tehri in the 15th century and the town grew gradually in the

intervening centuries. That is till the mid nineteen sixties and the coming of the motor

road. Pilgrim traffic has been going up in a geometric progression ever since and hundreds of thousands now

pay obesiance at Badrinath, every year.

In early November the shrine closes, after elaborate rituals, and a day or so later the entire town is closed, road access being

prohibited, till May the next year. During winters, because of the altitude, Badrinath gets many meters of snow and the only

people left in the region are detachments of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police and Militiary Intelligence.

Neelkantha has been called one of the most accessible peaks in the Himalaya, as

well as one of the most beautiful. Yet, the accessibility is more appearance than fact, for Neelkantha has so far been

scaled only twice, that too in an area overrun by mountaineers. The height diffrential between the peak and Badrinath

town is 3500 metres or ten and a half thousand feet in a short interval of only 9 kilometers.

Also, as mountaineers have noticed, Neelkantha is a mountain with formidable defences. Long pinnacled ridges, steep avalanche

prone faces and unpredictable local weather conditions, have combined to turn away even the very persistent.

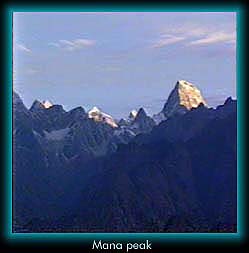

To the northeast, 36 kilometers beyond Badrinath, is another impressive grouping - almost on the Indo-Tibetan border

with Mana and Kamet as the principal peaks. Mana itself marks the eastern extremity of the Zanskar range and lies between

the pass of the same name and the Niti pass.

To the northeast, 36 kilometers beyond Badrinath, is another impressive grouping - almost on the Indo-Tibetan border

with Mana and Kamet as the principal peaks. Mana itself marks the eastern extremity of the Zanskar range and lies between

the pass of the same name and the Niti pass.

Upper Garwhal is inhabited by tribals of mixed Indo-Tibetan descent. One of the more

important tribes are the semi-nomadic Marchas of the Mana and Niti valleys.

Mana village, just north of Badrinath, is the last village on the old trade route to Tibet, via the Mana pass. In those days,

Mana must have been a big and prosperous village, references being made to it in 1624 by Jesuit priests trying to reach

the Tibetan kingdom of Guge.

Inhabited by people of mixed Indo-Tibetan descent, Mana, like Milam in Kumaon, survived, or rather thrived, on Indo-Tibetan

trade. The Chinese invasion of Tibet, and "inner line" restrictions on the Indian side, saw an end to the trade, depriving

Mana of it's reason for existence in these harsh and rarified altitudes. Today, they survive by doing menial jobs or petty retailing

during the pilgrim season in Badrinath. In winter, the entire village moves down the valley, cattle and all, to wait out the

winter snows.

Some 45 kilometers from its starting point, the Alaknanda meets up with the Bhiyundar Ganga. This is the route for the

Bhiyundar glen, or the famed Valley of Flowers, as it is popularly known. Frank Smythe, an English mountaineer stumbled

upon this beautiful alpine valley while returning from an expedition to Kamet, in 1931. It was Smythe's book "The Valley

of Flowers" that caught the public imagination and catapulted this remote high altitude valley in Garhwal to being the mecca

for nature lovers and enthusiasts from all over the globe.

The approach to the valley is itself beautiful enough, through dense forests of oak, spruce and further up, near the tree

line and above, the silver birch.

The Valley of Flowers itself, is a classic U-shaped glacial valley, moulded by the periodic convulsions of the Tipra-Kharak

glacier. Over the 60 odd million years that have passed since the Himalayas arose from the Tethyan abyss, the glaciers

have advanced and receded many times. Since the last Himalayan Ice age, the glaciers have been receding and what we

see in the Himalaya today are but mere shadows of their former selves. But nature, as they say, abhors a vacumn and what

the glaciers left behind was morainic soil and debris on which took root the myriad varieties of tiny alpine flowers that,

come august, turn the valley into paradise.

The attention the valley recieved over the decades, rebounded on it when it bacame the subject of environmental crusading.

It's doom was paradoxically sealed when it was declared a National Park in 1981, and placed off-limits to migratory graziers.

No attempt was made at the time, either by agitated environmentalists or the concerned ministry, to determine the precise

positioning of these graziers and their flocks in the extremely delicate alpine eco-systems. The surface evidence showed

that sheep ate up vegetation and so, obviously, the solution is simply to ban the sheep. In the case of the Valley of Flowers,

the ban resulted in the baby being thrown out with the bathwater. What has happened over the last decade and a half

is simply the invasion by a tenacious weed by the name of Polygonum, and since the sheep, which had a liking for it, were so

conveniently removed, it has swamped the more delicate alpine flowers which made the valley famous.

The tall plant, with numerous pink flowers, shorn of it's natural predators, is tough and has great regenerative capacity.

Thus unsurprisingly, weed control measures have met with little success. Instead the pastel hues of the alpine meadows have

given way to large, broad patches of pink as the ever expanding Polygonum elbows aside the smaller and more delicate

varieties of alpine flowers that so charmed Smythe and generations since. The ministry of Environment needs to rethink the situation in terms

of grazing, not only for the Valley of Flowers, but also for relevant and non-intrusive Himalayan policy planning in the future.

For example, in the Valley of Flowers, the scenario worked somewhat like this.... The annual upward migration of the sheep takes

place in May-June all over the Himalayas. At this time the Polygonum plant is a tender shoot, bigger and broader thena the alpine

varieties, and so proves a tasty target for the sheep. A late flowerer, Polygonum is again just in time for the return of the

sheep in September, and in the past, this twice yearly inroad was sufficient to keep their population in check.

The entire valley of the Alaknanda is rich in wildlife. The lower hills, once famous for man-eating leopards, are today too

overpopulated for wildlife to be easily visible. But it's there .. barking deer and leopards, musk deer in the Kedarnath region,

and as we get higher, the Snow Leopard and the Lynx. Splendid long tailed monkeys with black faces swarm through the trees,

while high above, taking advantage of the thermals from the heated rocks below, a Lammergeier can often be spotted. Practically

the largest bird in the Himalayan skies, the Lammergeier or bearded vulture, has a wingspan of 9 feet from tip to tip. Often

miscalled Golden Eagle it ranges between four to twenty thousand feet. It's eagle like appearance apart, it is a scavenger though

it is often rumoured to pick up small sheep and the like. Dr. Salim Ali, the fountainhead of Indian ornithology, dismisses

this and calls it "a scavenger pure and simple".

Trekkers will ofcourse see plentiful Bharal and maybe, if the're high enough and lucky enough, Ibex.

The Bharal is known as the Himalayan blue sheep though strangely enough, it is neither

blue nor is it a sheep. Taxonomically it is a cross between a sheep and a goat though larger

than either. Incredibly sure footed, Bharal are rarely seen by most Himalayan visitors

because they prefer elevations of above 14,000 feet, only coming lower in the winter.

They also seem to prefer precipitous slopes, the crumblier the better and foraging on the

alpine grasses they move in herds of upto 50 or more animals, though smaller parties

diverge here and there during the day.

The entire valley of the Alaknanda is rich in wildlife. The lower hills, once famous for man-eating leopards, are today too

overpopulated for wildlife to be easily visible. But it's there .. barking deer and leopards, musk deer in the Kedarnath region,

and as we get higher, the Snow Leopard and the Lynx. Splendid long tailed monkeys with black faces swarm through the trees,

while high above, taking advantage of the thermals from the heated rocks below, a Lammergeier can often be spotted. Practically

the largest bird in the Himalayan skies, the Lammergeier or bearded vulture, has a wingspan of 9 feet from tip to tip. Often

miscalled Golden Eagle it ranges between four to twenty thousand feet. It's eagle like appearance apart, it is a scavenger though

it is often rumoured to pick up small sheep and the like. Dr. Salim Ali, the fountainhead of Indian ornithology, dismisses

this and calls it "a scavenger pure and simple".

Trekkers will ofcourse see plentiful Bharal and maybe, if the're high enough and lucky enough, Ibex.

The Bharal is known as the Himalayan blue sheep though strangely enough, it is neither

blue nor is it a sheep. Taxonomically it is a cross between a sheep and a goat though larger

than either. Incredibly sure footed, Bharal are rarely seen by most Himalayan visitors

because they prefer elevations of above 14,000 feet, only coming lower in the winter.

They also seem to prefer precipitous slopes, the crumblier the better and foraging on the

alpine grasses they move in herds of upto 50 or more animals, though smaller parties

diverge here and there during the day.

West Garhwal

West Garhwal