| Details of my grandfather's travels and

anecdotes are contained in a set of memoirs written after his retirement. In

1988, during a 4-month European sojourn, I made an attempt to trace the

birthplace of my father in Lesbury. I was also able to verify and

embroider on important detail contained within the memoirs themselves and to

find record of the visit of Harry Lauder, famous Scottish folk and

dance-hall singer, to Alnwick Convalescent Camp, as my grandfather had taken

a couple of photographs marking the occasion. Harry Lauder's son had been

killed at the Battle of the Somme and had been assigned to the

Northumberland Fusiliers at Alnwick. The ballads of Harry Lauder were indeed

passed on from generation to generation, as I recall my own father often

amusing us with his renditions of "A wee Deoch an' Doris", "Stop yer

tickling Jock", "Roamin' in the Gloamin'", "I love a Lassie", and so on.

Details of the precise nature of my investigation in Alnwick in 1988, which

turned out to be an incredibly rewarding and fascinating experience for me,

as well as extracts from newspaper articles dating back to 1916, are

contained on this website. Subsequent to the original creation of the

memoirs of my grandfather, Edward Groves, the document has been edited into

a number of chapters, as outlined below. Chapters 1 and 7 in their entirety

follow! Edward Groves died on the 8th July 1961.

CHAPTER 1 - ENLISTMENT IN THE QUEEN’S ARMY.

CHAPTER 2 - OFF TO INDIA.

CHAPTER 3 - THE FRONTIER.

CHAPTER 4 - DOUBLE PNEUMONIA.

CHAPTER 5 - A CORPORAL ONCE AGAIN!

CHAPTER 6 - RABIES AND PARIS.

CHAPTER 7 - HOME, SCOTLAND AND JESSIE.

CHAPTER 8 - RETURN TO INDIA.

CHAPTER 9 - ALLAHABAD TO BAREILLY.

CHAPTER 10 - A NEW ROLE AND ANOTHER DOG BITE!

CHAPTER 11 - RESCUING SNOWY.

CHAPTER 12 - SNAKES.

CHAPTER 13 - TO RANGOON.

CHAPTER 14 - A TOUCH OF MALARIA.

CHAPTER 15 - FAMILY REUNION.

CHAPTER 16 - BACK WITH THE REGIMENT.

CHAPTER 17 - ON TO SOUTH AFRICA.

CHAPTER 18 - 18 YEARS IN THE SERVICE.

CHAPTER 19 - HOME VIA CAPE TOWN.

CHAPTER 20 - PREPARING FOR THE WAR.

CHAPTER 21 - FACING THE ENEMY.

CHAPTER 22 - WOUNDED, THEN ON THE MOVE....AGAIN!.

CHAPTER 22 - ALNWICK.

CHAPTER 23 - THE FINAL CHAPTER.

CHAPTER 24 - UNEMPLOYED...THEN SOUTH AFRICA.

Chapter One - Enlistment in the Queen's Army

I joined the Third Militia Battalion

Royal Fusiliers in May, 1893, and did the annual training at Hounslow. The

following year, at St. George's Barracks, London, I enlisted in the Second Royal

Welsh Fusiliers. It was rather late in the evening when Jimmy Jackman and I

routed the recruiting sergeant from the sergeant's mess, but as we were worth

five bob each to him, this being the sum a recruiter received for all recruits

of the line, he took us to the reception room, found us beds, and gave us each a

shilling, part of which we spent in the canteen. There were a number of other in

the room, and we were long in getting down to it.

Being almost in the centre of

theatreland, we sat at the window overlooking Trafalgar Square, and talked about

the times that we had ducked each other in the fountain basins, and had then

walked home to dry ourselves in someone's backyard before a big pail fire, made

with coke and coal we had pinched on the way. I lay a long time wondering what

my mother, sisters and brothers were thinking about my absence from home, as I

had never once been away without their knowledge. They soon found out next

morning. After breakfast and a very chilly bath, we were individually examined

by the Medical Officer. I was passed fit, A.1., as also was Jackman, and then in

a body the whole crowd was handed bibles and sworn to "Serve Her most gracious

Majesty, Queen Victoria and all Heirs and Successors to the Throne, for a period

of 12 years, 7 with the Colours and 5 with the reserve, so Help me God"- kiss

the book and march out. We mustered on the barrack square and marched off to

Charing Cross station.

|

|

As we emerged through

the barrack gate, I saw Mother and brother Bill waiting there with many

others. My heart sank to my boots when I saw her step forward and in her

best fighting voice say "Come on, my boy, no damned soldiering for you".

Without halting us, the recruiting sergeant raised his hand and said "You're

too late mother, he now belongs to the Queen". This brought tears to my dear

old mother's eyes, but she very bravely followed us to the railway station,

and saw us off, putting a half sovereign into my hand and kissing me for the

first time I could remember.

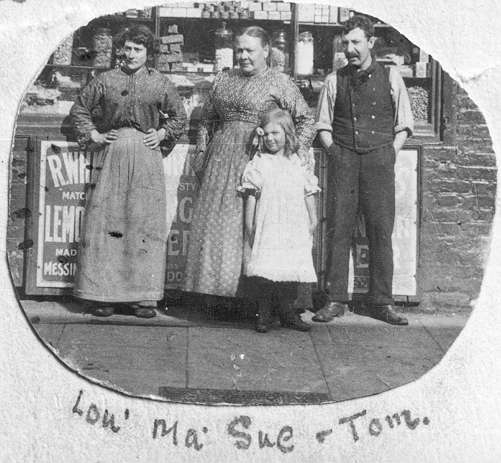

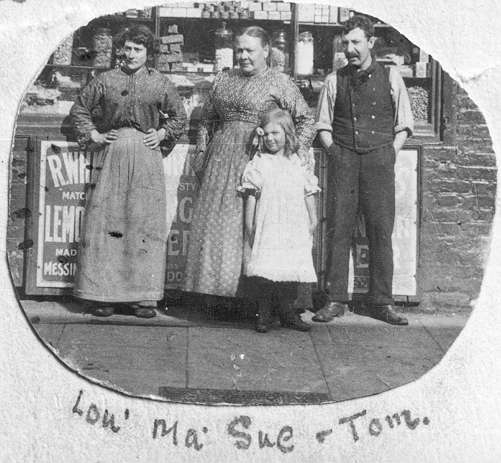

The only known photograph of "ma" Groves, possibly taken outside the

greengrocer owned by her in London. Here she is flanked by Louie, wife of

Bill Groves and one of her sons, Tom Groves, brother to Ed Groves, my

grandfather. Also in the photograph is Sue, daughter of Bill and Louie. |

Now we were off on our great adventure!

Arrived at Aldershot, the biggest training camp of those days, we were met by

Garrison Military Police, who took us to the various regiments to which we were

posted, and handed us over to the orderly room. We were posted to A Coy. and

told to report to our Company Office, but as the regiment was out on a field

day, the whole barracks was empty. We had a look into the rooms, which appeared

to our minds to be like so many stables or barns, with twenty beds along each

side, all made up like rows of soldiers on parade, tabled in the centre, with

plates and tea basins, big enough to wash in, all set out for a meal.

This sight depressed us very much, and

the fact that there was no one there to welcome us, together with the thoughts

of my mother's tears at losing me, turned us both against being soldiers, and we

decided to walk back home to London. We had the weird idea that as long as we

had not worn military uniform, we could not be charged with desertion. After

getting our direction from a civvy, we started on our long 45 mile walk back

home. I had over nine shillings in my pocket and Jack had 1s. 3d., but we felt

we could make it by stopping at village pubs and doing little street acrobatics.

Jack also had a tin whistle on which he could rattle a decent tune.

We had done about three miles, and were

just passing through North Camp, when we ran almost into the arms of Garrison

Provost Sergeant, who had seen us arrive at the station that morning, had

recognised us at once, and had guessed what we were up to. He was a big brawny

Irishman, and had a face that would terrify older men than we were, with a pair

of really cross eyes. "Where are you boys off to", says he. I replied "We're

just going for a walk until the troops get back". He replied "Well, I heard the

bands of the South Camp playing some time ago, so they must be in now. Come

along with me, and I'll show you a short cut to barracks". And taking me by the

arm in a fatherly fashion, he walked with us all the way to the barracks,

talking to us in a very nice way, and telling of his long service with his old

regiment. Then he handed us over to our company.

After a meal, we were taken to the

Quarter-Master Stores, issued with our complete kits, and ordered to be on

parade with the recruits the following morning. Our previous training with the

Royal Fusiliers enabled us both to pass through the recruits squad in two weeks,

into the rifle squad, which we found difficult, as we had before trained with

the old Martini rifle, which was superceded by the Lee Enfield, and the

mechanism of these rifles was entirely different. However, determined to get

away from the recruit's drill, we did extra private practice in the barrack

room, and after about three months, were dismissed and became duty men or no. 1

soldiers.

Shortly after this, we were both

recommended for staff jobs, I as an Officer's Mess waiter, and Jackman as an

Officer's batman - both jobs carried an extra ten shillings a month, with the

very great privilege of wearing civvy clothes for walking out. We also wore them

on duty, mine being an elaborate livery at nights, and a dark grey one for day

use. After rough handling on the barrack square and the rough and tumbles in our

barrack room, the atmosphere and meals in the mess proved most agreeable for a

time - and then the very long hours at my job began to tell. The duty waiter

came on at 7.30 p.m. and remained on duty until 7.30 p.m. the following day,

often waiting until the small hours before closing the mess. This happened every

third day, but often every other day. Owing to this, I told the mess sergeant

that I wanted to leave the mess and go back to regimental duty. He refused to

consider this, and I then asked to see the Mess President, Capt. Engleheart.

When I told him about the long hours on duty, he offered to put this right, and

I decided to wait and see.

Meanwhile, it got about the mess, and

the scullery man, who wanted badly to be a waiter, asked me if I would swap

jobs. We saw the mess sergeant and it was all settled. Poor me! I had not the

least idea what I was letting myself in for! From early morn till late at night,

it was a continuous wash, wash, wash. Running for the lift, back to wash up, and

even the kitchen crocks were all pushed my way - for a time; but I soon scotched

that. Every time a pile of plates, etc., arrived in the lift from the dining

room, there was a general yell of "Crocks!" from half a dozen voices, and you

have no idea how this annoyed me. I protested strongly and asked if some other

means could not be devised, but it was only after my third fight with the

kitchen staff that the mess sergeant had a bell rigged up, and he did not even

have to warn anybody about "Crocks" anymore.

It follows that in handling such a

number of plates, cups, etc., every day, there would be breakages, but this the

mess sergeant would not see, and was always examining the rubbish bin, and going

off the deep end at every broken piece he found. I certainly was responsible for

most of the breakages, but quite a lot was put there when my back was turned, by

others; but the blame always came on to me, and so fed me up that I started

hiding my breakages.

Right above the wash up, was a very

large cistern with an opening to control the ball cock; I found this most

convenient, and must have dumped enough broken china to do a good-sized family,

and I began to wonder when it would reach to the top. However, I was saved

further worries, as the regiment was ordered to proceed to Manchester, to

garrison that city, and in October, 1894, we entrained at Aldershot during the

afternoon, and arrived in Manchester the next morning.

An advance party of the regiment had

breakfast of hard-boiled eggs and tea ready on the platform, and after a scrappy

wash and brush up, we paraded in full ceremonial kit, busbies and all, and

marched through the city to the old barracks in Regent Road , with crowds lining

the streets to welcome us.

On arrival at the barracks, the

companies were detailed to their various barracks, and it was our good fortune

to get to those near to the main road, where we could look from our rooms on to

the passing tramways cars and buses, and exchange uncomplimentary civilities

with the passengers on the open upper decks.

Regimental duties were fairly heavy,

with a barrack gate guard, magazine guard two miles from barracks, and a

Governor's guard, besides inlying pickets, two each night, from Retreat to

Lights out - 6 p.m. to 10.15 p.m. This last duty was detested by every soldier,

as we had to parade through the centre of town, a party of ten men under a

corporal and a sergeant, walking very slowly, all in perfect step, on the

look-out for any disturbances or drunkenness (soldiers only, of course), with

invariably several abominable brats following us at a safe distance, singing

that song that caused more cussing amongst soldiers than anything else I know -

"Army Duff", and keeping marvellous time to the steps of the party. All the

time, every man of the picket would be boiling with rage, and would cheerfully

have strangled everyone of those kids.

I, of course, went back to my job in

the mess, but it did not last long, as with the number of regimental guests that

were being entertained, the washing-up almost doubled, and I asked for an extra

hand on the job; but the mess sergeant thought this a big joke, and I threatened

to walk out on him if nothing was done. That night, after finishing, I packed up

my kit and left for my barrack room, and heard not a word from the mess.

Evidently another man was detailed to help in the wash-up, and turned up the

next morning, starting off where I had left off.

After a few weeks at duty, I was made a

Lance-Corporal, and how proud I felt, until I found that I had to attend school

to get my certificates. I could not fall in with this idea at all, and wondered

why they wanted me to go back to learn my A.B.C all over again. As I had long

forgotten the little that I had learned, I felt, and was, an absolute dunce.

Result, I remained absent from school so often, that after many reprimands, I

was deprived of the Lance-Corporal stripe.

My Company Commander, Capt. the Hon.

Robert White, was so keen on promoting me again, that he offered to take me in

hand in his quarters and to teach me the simple three "R'S" that the school

certificate required, but whilst I was thinking this over, he was ordered to

South Africa to take over a detachment of mounted police. He was later taken

prisoner with Dr. Jameson and others who took part in the Jameson Raid.

Soldiering in Manchester was not at all

bad, and there was much entertainment available when off duty. The Y.M.C.A. and

Army Temperance Association, of which I was a member, both arranged outings and

concerts, and we were often taken to some civilian friend's home and

entertained, but a letter I received from my pal Bill Scott, who was in the

Royal Scots Fusiliers, telling me that his regiment was gazetted for service in

India the next year, decided Jackman and I that we would go to Aldershot where

the Scots Fusiliers were now stationed and join that regiment.

When we had originally enlisted in

London, we had wanted to join the Royal Scots Fusiliers then, but as that

regiment was closed to recruits, we were told that we could join another

regiment and if, after a few months, we were not satisfied, we could apply for a

transfer. We naturally fell for this, and applied so often that we both became

marked men and decided to walk out - in fact DESERT! Jackman, still an officer's

batman, had his civvy clothes, but I had sold mine. Jackman, however, managed to

buy a suit from another batman.

On the night of March 5th, 1895,

dressed in civvies, with our regimental red stripe trousers and greatcoats, we

were inspected at the main gated guard room, and passed "fit to parade the

streets of Manchester". It was fairly dark and a slight rain was falling, so we

made our way to the ship canal and at a quiet spot, took off our greatcoats and

trousers, rolled them in a bundle each with a brick inside. tied them with our

belts, and dropped them into the water. We each had carried a civvy cap in our

coat pockets, and were now two quite respectable young men, at least we thought

so - for the way I looked on it, although we were committing the crime of

desertion, we were not really deserting the service.

So as to put as much distance between

us and Manchester as possible, we walked all through that night, and daylight we

made for the first haystack we came to, and slept happily for six hours, and

woke some time after noon feeling fresh but a bit stiff. We went to the

farmhouse to ask for a drink of water. The maid called the farmer's wife who

questioned us, and had us sit in the kitchen dishing up a big jug of milk and a

pile of buttered scones. What a glorious feed we had. What we could not eat,

they insisted we take with us for the road. After sawing and chopping a big pile

of firewood, we continued on the road, resting by day, and walking at night,

often getting lifts on farm wagons and carts on their all night treks to

markets.

In this manner, we made slow progress,

but we fared well and were never hungry. Several days had passed when we emptied

our pockets and found that we had just enough cash to enable us to finish our

journey by train, and so at Leicester we bought tickets to Guildford in Hants,

where Jack had a married sister living. We arrived late at night and slept on

sacks in a tool shed at back of the house. The cold kept us awake most of the

night, and we were glad when daylight came, to hear movements in the rooms.

Jack's brother-in-law was a farm worker

and had to leave very early for work, so we decided to lie low until he had

left. Shortly after he had gone we made our appearance at the house. Jack's

sister was pleased to see us, but seemed a bit puzzled at our being in civvies.

Her mind, however, was set at rest when Jack told her we were both officers'

servants, and had travelled to Aldershot with our officers, who were down on a

course of training, and had gone to London for a week-end, giving us the two

days off.

We had breakfast and dinner with them,

and left with the intention of finishing our journey to Aldershot, but after a

long argument, Jackman decided to go home to London. This he did. I reached

Aldershot that night, and found one of my pals, Lance-Corporal Bill Scott, who

took me along to the reception room, where I bedded down for my first night in

my new regiment, the First Royal Scots Fusiliers.

The next morning, myself and two other

were marched to the Cambridge Hospital for examination, and after passing the

inspection, were taken to the orderly room, and sworn in and posted to H

company, on March 11th, 1895. This made an absence of six days, but I was still

guilty of the crime of fraudulent enlistment, which carried a very heavy

punishment. Still, this did not bother me very much, and now that I had attained

my objective, I was reasonably happy.

I had a company commander, Capt. W.

Douglas-Smith, who took an interest in me, and a grand colour sergeant, that

great little man, Billie Bailie. The men in my barrack room were a decent lot,

but there were invariably some Scots versus English controversies, and we were a

regiment of half and half. There were often serious fights over the most

trifling incidents. One thing that stands out very clearly in my memory, is a

day when Ginger Wilson was being arrested for using threatening language to an

N.C.O. Two men were ordered to escort him to the guard room, when Wilson

suddenly snatched his rifle from the rack, fixed his bayonet and threatened to

kill the first to come near him. Suddenly a door opened behind us, and a

lance-corporal just returning from his gym practice, saw everyone transfixed and

the man with his bayonet fixed and standing at the ready. Grasping the situation

at once, he coolly picked up a long handled dry-scrubber, engaged Wilson, made a

feint causing Wilson to drop his guard, and lance-corporal Dan Reid drove

straight for his chin - broke his jaw and knocked all his front teeth out.

Wilson was rushed to hospital on a stretcher and patched up, and a court of

enquiry was held next day, when the corporal was exonerated from all blame and

Wilson was discharged as medically unfit for service.

The whole army then went out on Autumn

manoeuvres in the area of the New Forest in Hampshire, and we made camps at

Alton, Arington, and finally at Baddesley, where we stayed several days. We were

entertained at Winchester by the inhabitants of the cathedral city, who had very

long tables fixed up by the roadside, and as the regiments on that route reached

the tables, they were halted and served with tea or coffee and lashings of cake

and sandwiches by the lassies of the town.

We marched to our standing camp at

Baddesley, where the whole camp had been pitched ready for occupation and I was

warned by our orderly sergeant to report at the officers' mess marquee. My pal,

lance-corporal Scott, had recommended me as a waiter to replace one who had

reported sick on the march, and I was sent to fill the gap temporarily.

As this excused me from all parades,

night marches, attacks at dawn, etc., I was glad to take on the job, which I did

with confidence after the training I had had in the Welsh Fusiliers. I had quite

a thrill when I served the old Duke of Cambridge with a whisky and soda, for he

had commanded the famous Guards Brigade at the Crimean war and was seeing his

last parade that day.

One night when on duty as waiter for

the night, I closed the mess at 1.30 a.m. and went to my tent feeling very tired

and sleepy. There were six of the mess staff there already asleep, and as I

could not find my roll of blankets I lit a candle and began to search for them.

One of the men awoke and told me that Bill Morris, the assistant chef, had taken

them and I commenced to shake Bill awake. He told me to "go to the devil", and

not to disturb everyone in the tent. That made really see red. I took him by the

heels and dragged him, blankets and all, out of the tent, grabbed my two

blankets and waited. Bill got up, picked up his own blankets and walked into the

tent, with me following. Nothing further happened, and the incident was

forgotten. At the end of the manoeuvres, the troops struck camp, and marched

back to their various stations, and shortly afterwards the Commander-in-Chief,

General Sir Evelyn Wood, instituted a competition, open to all regiments in the

service. It consisted of a march, in full marching order, and firing 20 rounds

down the range, from 1000 yards to 200 yards.

There were 57 entries and most

regiments picked a team of 20 good shots. Some had entered two teams, but our

colonel decided that each company of the regiment should have a team, and so we

had eight teams. We were to march to the ranges at Pirbright, which were 15

miles from Aldershot, and points were awarded or substracted for march

discipline by the umpires who were posted at points along the route. What a

march it was! Trotting, stepping out and stepping short, but not a halt until we

reached the ranges. Out of the original 57 teams entered, nine were to be chosen

for the final - the Royal Scots Fusiliers had seven out of their eight teams in

the final, and ten days later, the competition was won by B. Company, R.S.F.

I was absolutely exhausted at the end

of the march and when lying on the ranges after firing at 1000 yard, I simply

could not get up again, until our Company sergeant took a grip on my pack and

pulled me up.

I swore that I would never tackle a

thing like that again, but three years after, in Peshawar, we did a similar

march, and my company came first.

I was kept on permanently in the

Officers' Mess, but in spite of the many privileges, I was not happy there as I

would have been in the barrack room with my pals. The mess sergeant, Smart

Walker, was considered amongst the finest mess caterers in the army and liked to

get all he could in the way of work out of his staff. He would walk behind one

and keep digging one in the back to hurry you along, saying "Come one, come on,

come on", until one day he punched me rather hard, which I resented. I turned on

him and said "Do that again, sergeant, and I'll make you sorry you did it". He

looked around for someone to act as second evidence, so that he could put a

charge of insubordination against me, but no one was there, and after further

words, I asked to be allowed to go to my regimental duty. He refused, and when

he left I changed out of mess livery, got into my regimental clothes and walked

out to my barrack room.

Half-an-hour after, the mess corporal,

Ned Spiers, and private Harry Beaumont arrived to escort me to the guard room,

and on the way up, we met the mess president, Capt. De la Bere, who lectured me

on the crime of deserting my post, and then ordered me back to the mess. On

arrival, I saw the mess sergeant grinning and he ordered me to get into my

livery again, which I would not do. After he had consulted with the mess

president, he told me to pack up and go to the devil. And so I returned to duty

again. That night, at roll call, when the company orderly sergeant was giving

out the orders for guards, pickets and fatigue, I was detailed for officers'

mess fatigues. And I was put back on the same job that I had left - waiting at

table in my regimental clothes, and doing the ordinary work of a waiter during

breakfast and lunch. This was because several waiters were doing their annual

musketry course, which kept them at the ranges all the afternoon. I did not

mind, as I had breakfast and lunch in the mess, and the mess sergeant and I

became very good friends.

During this time, I answered the front

door bell one day, and found a young parson there, who enquired for a Lieut.

North, whom he said was his brother. I led him to the officers' ante room, and

announced him to several senior officers sitting there reading, expecting at

least one of them to invite him to a drink, but as no one took any notice of

him, and the silence became embarrassing, he left the room without a word, and

asked me to direct him to the field where his brother was playing cricket for

his company, and left at once. In a short while we heard the sound of a battle

coming from the ante room, and found it was caused by this officer laying into

all those senior officers who had treated his brother so shabbily. Peace was

eventually restored and after an enquiry by the C.O., at which I had to give

evidence of announcing the Rev. Mr. North, Lieut. North was quietly sent on

leave which lasted twelve months. He was later wounded in the stomach at the

battle of Ubaln Pass, on the North West Frontier, India, and retired from the

service.

When the other waiters returned to the

mess, I was allowed to leave, and shortly after, the regiment was gazetted for

service in India, and the battalion commenced their furlough, half the battalion

leaving at once, whilst the other half remained, and did most of the packing of

stores, equipment, etc. My mother was very distressed when she received news of

my going to India. In fact, the whole family was greatly upset, but in spite of

this, I had a very happy month's leave. They gave me a great send-off at

Waterloo station - all my brothers and their wives, and dozens of uncles and

aunts. I did not then say a final good-bye, as I could get a weekend pass before

leaving England, which I did on two occasions.

We who had had our leave spent the time

finishing packing and loading, leaving nothing but our kits, and rifles and

equipment to take aboard the ship. We sailed from Southampton in September,

1896, and my dear old mum and sister Mag1 were both at the dockside

and I was allowed to spend a few minutes talking to them before embarking.

A little incident which happened in the

mess has just come to mind, and is, I think, worth recording. During the firing

of the annual musketry course, another waiter and I were ordered to spring clean

the ante room, lift all carpets, take out all pictures and curtains and

thoroughly scrub it out, all in one day. During the time that we worked on this,

the few officers left in barracks had part of the dining room screened off, and

I started in at 6 a.m. and made the dust fly. But we found we could not finish

before 11 p.m. It was too late to return to our barrack rooms, and as we had to

serve breakfast at 6 a.m. the following day, we decided to camp out on the ante

room couches, using the heavy curtains and rugs as covering. Just as we were

beginning to prepare to get down to it, there came a violent knocking on the

door, and a voice cried out "Who is in there? Open this door!" We both

recognised the voice of adjutant, Capt. W.H. Bowes, and remained almost

paralysed with fear. But after a few moments, Beaumont stepped forward and

opened the door, and we saw the adjutant standing there pointing a service

revolver and holding a candle stick. He had heard us moving about the ante room

and living just above, could hear quite plainly and thought we were burglars. He

had us both placed in open arrest, and the following day we were brought before

the C.O. at the orderly room, and charged with sleeping in the officers' mess

ante room. I began to have visions of a trip to the dreaded glass house. When

asked what we had to say, Beaumont explained our reasons and the colonel took a

lenient view of everything, and on account of our youth, dismissed the case,

after telling us that on no occasion must we ever sleep in the officers' ante

room.

Chapter Seven - Home, Scotland and Jessie

I was given a large packet of ham

sandwiches and two half bottles of brandy to see me over the Channel, and I

embarked at Dieppe on the paddle steamer Atlanta. This good ship did everything

except stand on her head, but I was not the least upset and thoroughly enjoyed

my fat ham sandwiches. But the brandy I swopped with the bar steward for two

pints of stout. We were four hours in crossing and what a crossing. It was ten

times rougher than the whole fourteen days trip from Bombay to Marseilles. The

stewards brought along small oaken tubs, one to each passenger, and they were

very angry when I told them that I would not require one. One of them watched me

like a hawk, waiting to shout "I told you so", but I did not feel the least bit

squeamish.

Mag, sister of Edward Groves. |

|

We reached Newhaven at

4 p.m. and embarked on the London express which was standing on a platform

beside the docks. My instructions were that I should report to Thos. Cook &

Son on reaching London, for further orders, but as it was too late to call

at their offices, I decided to go home and see my people first. So I left

Charing Cross Station, crossed the Strans, along St. Martin's Lane, and down

Neal Street - HOME! What a feeling! Sister Mag was out sweeping the

pavements when she spotted me walking down the street. She dropped her broom

and rushed into the house calling "Mother, here's Ed!" All was confusion. In

a matter of minutes the whole street knew Eddie Groves had come home, and we

made a night of it with my brothers and sisters. They wanted me to go out to

a pub, but I preferred to stay in the house until I came on leave proper,

which I knew was to be granted.

The next day I presented my certificate and papers at Thos. Cook's and I was

asked "Where do you want to go". Here was a problem that required careful

thinking. Our 2nd Battalion was in Aldershot, but I had quite enough of that

station. "What about the regimental depot in Ayr?" I was asked, to which I

replied "Yes sir, send me to Scotland", and a warrant was presented to me

enabling me to travel by rail to Ayr, Scotland.

Before leaving, I spent another day

at home and then left for Ayr, promising to be back again very soon. Being

my first visit to this delightful town, I was very happy upon detraining. On

reporting at the orderly room, I was met by an old friend, orderly room

sergeant Bob McDonald, who went in to report to the Commandant, and out came

another old friend who had been on the recent Frontier expedition, the one

who proposed a grant of one hundred rupees to me from officers' mess fund in

appreciation of the good work I had done when in charge of the mess on

service. This was Major Frere. |

He took me inside the orderly room and

seated me at a table and made me recount all that had happened. When I had

finished he asked me whether I would not like to take over the depot officers'

mess. Of course I could not refuse a plum job like that, but I did not show my

eagerness and told him that I had a widowed mother who would be glad to see me.

He then gave me six weeks furlough on condition that I took over the mess on

completion. I was made lance-corporal again, and left that night for London

where I spent a really fine holiday.

Having three brothers working in

theatres, I was able to get complimentary tickets to a good many shows, and at

quite a few I went back stage, being introduced to various actors and actresses

and generally having a very good time, until brother Bill had an argument with a

policeman one night when we were all leaving a pub at closing time. The

policeman gave Bill a hard shove and Bill resented this and gave the policeman a

fourpenny one. The bobby blew his whistle and when the others arrived was taken

to Bow Street Station and charged with "Drunk and striking". I followed down to

bail him out, but the Inspector on duty said "No bail for drunks", so Bill spent

the night in a cell. The next day he was fined 5pds, which I paid. We were

halfway home when the same policeman came up behind us, tapped me on the

shoulder and asked me to pull up my sleeve. Being in a rather busy street, I

said "I'd rather go back to the station with you". Knowing that he was going to

arrest me for my desertion from the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, I admitted that I was

the man he was looking for, but told the Inspector that I had already been

punished for this offence hoping to escape being stuck in a cell to await an

escort from Ayr. After taking my particulars, I was put in a cell, the Inspector

handing me my cigarettes and matches, a really big privilege. After only an hour

in the cell, I was released and told to come up for remand the following day.

Everyone at home was terribly upset at

my arrest and expected all sorts of awful things to happen to me, but I told

them the police had made a bit of a mistake and that they would find out in the

morning when they had a wire from Ayr. I had of course told the Inspector a lie,

and in a long letter which I wrote to the magistrate, I admitted having done

this, but told him that as I had not seen my widowed mother for some year, I was

anxious to spend as much time with her before being sent back to my regiment.

This letter I had intended handing to the magistrate from the box, but I had no

need to use it, for when I took my stand in court, he looked at me smilingly and

said "Lance-corporal Groves, we have had a telegram from your C.O. asking that

you be asked to rejoin your depot on the expiration of your leave. Will you

promise me to do this?". I promised and thanked him, shook hands with the

Inspector and the bloke who "took me up" and left the court all smiles. I had

been dreading this happening all through my service and was glad that it had

happened at last.

I had 10 days left and as the time for

departure grew near I wondered what was going to happen when I got back, feeling

sure that some form of enquiry would take place. But except for a word or two

from the orderly room sergeant, the whole affair was washed right out. The

service I had had in the Welsh Fusiliers was allowed to count as "service for

pension" however.

I took over the officers' mess from

corporal Tommy McNeil, whose wife was the mess cook, and was measured and fitted

with a new livery and a walking out suit. My previous experience with the 1st

Battalion mess proved most useful and I was able to carry on and run the depot

mess in a similar manner. The mess of course was a much smaller one that I had

been used to, with only eight or nine single members, and three or four married

ones, my staff consisting of a cook, one waiter, one kitchen and scullery man

and eight or nine officers’ batmen, who took turns at waiting at dinner. The

cook, Miss Hunter, an elderly woman from the North of Scotland, was a good one,

and we worked very well together, but she was a bit fond of her dram, and at

times, on one of your day trips to Glasgow, she would return "o'er jolly". She

then had to be bundled to her bed, the kitchen man and I doing the best we could

for dinner.

After a month or two, the Bogside race

meeting was due to take place and it was the custom for the officers to have a

large luncheon tent at this two-day show and invite their many friends to lunch

with them. Hitherto the luncheon had been run by an old Crimean War veteran, who

was employed as canteen manager in the barracks, and it was he who was to have

run it again, until I protested and pointed out how unfair it was to let a man

who did not know the first thing about catering have anything to do with it.

Major Frere settled it, pointing out to the officers my service on the Frontiers

with the mess and I was given the signal to go ahead. Old Bill Gaffney was

expecting me to ask him how much of this and that was required, but we

completely ignored him and made a big success of it - everything was in proper

mess style.

As soon as lunch was finished on the

first day, I phoned the cook, telling her how much to prepare for the next and

final day and these things were sent out in time for lunch. I had all my staff,

including the batmen, and all being in mess livery, we made a fine show. We had

engaged a four-in-hand mail coach (the real thing) to carry us, and the

left-over wines, etc. back, and left the tables, tents and other heavy gear to

come on a horse lorry. We were all thanked for the splendid way in which the

lunch had been run. We were a good many pounds to the good too.

I had only been three months at the

depot when I was invited to the wedding of lance-corporal Hugh Rennie, the

wedding being held at the house of one Mr. George Wyllie of Green Street Lane,

Ayr. There was nothing pretentious about it, just a small party of his personal

friends. Besides Mr. and Mrs. Wyllie, and bride, there were five girls, five men

and two Wyllie boys, Archie and Doddie, who were just small kids. We had a few

drinks and some sandwiches and things, and played games, and two of the men from

barracks, Harry Lee and Ted Latimer, could and did sing, and this encouraged two

of the girls, who both sang very well. When it became late, we suggested walking

the girls to their street doors, and when pairing off, Mrs. Wyllie made certain

that I had her daughter, but as she was already at home, I proposed we all walk

the length of the street and kiss the girls good night there. This we did, each

man kissing the four girls in turn and leaving them at the head of Green Street

Lane.

The next day, I sat thinking up ways

and means of paying another visit to the Wyllie household, without causing too

much speculation, and I thought it would be a grand idea to invite the same

party to a night at the Ayr theatre, where a London company was appearing in the

"Belle of New York". I sent one of the batmen to the Wyllie's house, and Mrs.

Wyllie vouched for herself and all the girls. So I phoned the theatre booking

ten seats in the circle. We assembled at the house half an hour early, and found

everyone dressed and ready. We commenced to pair off, I being allocated to the

daughter of the house, Jessie, by her mother and we all walked to the theatre,

took the ladies to the seats and left them there, whilst the men all adjourned

to the Whip Inn for a quick one.

After the show we walked to the house,

where we had a light supper and then went back to barracks. During the

performance I had much to say to my girl, whom I found out, worked at the

station cab office and arranged to meet her at the office the next day after

work. This I did for many days and it became clear to everyone that we were very

much in love. At week-ends she would visit me in my room at the mess and we

became very happy together.

After a couple of months I decided,

with Jessie's permission, to ask her father's sanction to marry, but he thought

that we had not known each other long enough, so suggested that we wait for

another three months. But this did not suit me, and after telling him that I

loved his daughter and that she loved me, and that we intended to marry as soon

as possible with or without his consent. I spoke to Mrs. Wyllie, who had a word

or two with the old gentleman, resulting in our arranging to marry in a month. I

applied for permission to marry at the orderly room, and this was granted, but

as no married quarters were available, I would have to live out. The regimental

conditions were that a soldier must have at least five years service and five

pounds in a savings bank. So, on a pay of one and three pence a day and in

September, we were married at the Free Gardiners' Hall in Ayr.

My grandmother, Janet "Jessie" Lawson (née Wyllie), circa 1900. |

|

I had written to my

mother as soon as we decided on our marriage, and she, with sister Mag and

brother Andrew, came up from London to look over the bride to be and attend

the wedding. She was perfectly satisfied with her future daughter-in-law,

although she told me when I met her on the train that I ought to have sought

a wife from my own town. She eventually became very fond of my choice. We

had at least a hundred guests - the sergeants from the barracks with their

wives and a host of relatives from all parts of Scotland. The officers gave

me two cases of champagne, the mess wine merchants supplied wines and

spirits, the butcher sent enough steak to the bakers who made six meat pies,

tremendous ones, and the shop from where we bought our crockery and glass

lent me all the articles I required. The marriage ceremony was a very simple

one. A temporary altar was built up and covered suitably and the parson, who

was well known to the family, made it all seem very easy. After the service,

he drank to our health, said good night and left us to it. We had a band,

made up of Uncle George Gebbie, Bob Fletcher, Billie McCrae and one whose

name I forget, and they kept them dancing until midnight. Early in the night

I had faded right out of the picture, through exchanging too many toasts,

and I was taken in hand by my mother and gently thrown on to a bed in the

caretaker's room. There I stayed until it was time to leave, I had no idea

how or when I reached my home, a little two-room-and-kitchen place in

Content Street. I only remember wakening very late the next morning and,

feeling very thirsty, went to the kitchen sink for a drink. It was very dark

at the time although it was summer, and I thought that I heard whispering

and giggling outside our door. I listened carefully and after making sure I

was right I opened the door and there, standing in broad daylight, were a

number of my wife's younger cousins. They had blackened all our windows to

fool us - it was then 10 a.m. They wanted to come in and make tea for us,

but my wife objected and I managed to shoo them all away. |

I had arranged with Freddie Fry and

Jack Pinchin to see to everything at the hall and return the china and glass. I

was given seven days leave, all I could get, as the Ayr races were taking place

two days after my leave would expire, and this was indeed a very busy week for

the mess.

That night with my wife, mother,

brother and sister, we boarded the London train, whilst a good crowd of Scots

relations and friends gathered to see us off. Arrived at Euston Station the next

morning at 6, we hired a four-wheeler (cab) and drove home to find them all

expecting us and with breakfast waiting. My wife won the hearts of all who met

her, and with her Scots accent and dainty figure she completely captivated my

elder brothers and their wives. We all rested most of our first day at home, but

after theatre closing time, they all gathered at mother's place and after a

couple of drinks, we had a little dance. It must have been near 2 a.m. when we

finished and turned in.

My brother Tom had brought us two

complimentary tickets for seats in the old Gaiety Theatre to see "The Shop

Girl". Before taking our seats Tom arranged to meet me at the pub, which we did,

but we took longer over it than we should have. When I returned, I found the

curtain up and the second act in progress and I could not very well get to my

seat which was right in the centre, without disturbing others. I stood at the

back waiting for a chance that never came. As the final curtain fell, I rushed

for the door and was out with the first rush, meeting brother Tom waiting for us

to come out. Whilst chatting, my wife passed us in the crowd without being seen

by Tom or me, and stood on the kerb nearby waiting for me. Not having yet seen

her, Tom and I made our way quickly inside, but only the cleaners were left,

covering the seats with the dust sheets. We were beginning to feel desperate by

then, and commenced to run around the block, and just as I turned the corner

into Southampton Street, from the Strand, I saw my wife standing on the edge of

the pavement sobbing bitterly with a big fat policeman standing near her. I went

quickly to her side and pacified her as well as I was able, explaining to the

policeman what had happened. He was most apologetic and told me that he had

watched the girl standing at the theatre exit scanning the crowds as they came

out and when asked what she was waiting for, replied that she was waiting for

her husband. When asked where she lived, she could not tell him, as she had not

the foggiest idea, could not even tell him in what direction it lay, and so he

concluded that she was up to no good and moved her on. Tom joined the party and

began to shoot his neck out at the policeman, so we called a cab and drove home.

My wife was so distressed over this incident, that she would not let me leave

her for a moment whenever we were out together after that, and the remainder of

our leave passed without further trouble. We spent each evening at a theatre or

music hall, taking someone of the family with us, and after a really good week

of sightseeing in London, and parties at night, we returned to the Land o' Burns

again and settled down to work.

The Ayr races Western meeting came and

kept us very busy and my wife came along to help the old cook in the kitchen.

Things moved smoothly until the cook began to nibble at the bottle and several

nights running had to be put to her bed. Then one night when she came into the

mess, nicely loaded, and tumbled on the stairs down to the kitchen, we had to

fetch the doctor for her. When he saw the state she was in he had to report to

the Commandant. She was kept to her bed for a week, during which time my wife

took over in the kitchen. Aunt Mary McKenzie being in Ayr on holiday at the

time, and being a first class cook, helped a lot. In fact, she did most of the

work. Miss Hunter, the cook, decided she would like her discharge and she left

the mess to return to her home in Stornaway. My wife, assisted by her Aunt, took

on the job and proved most satisfactory.

I was promoted full corporal and on the

same day that my promotion was in Depot Orders, I was called to the Ante Room

where I found all the officers present and was handed a beautiful French

regulator clock with all the officers names engraved on it. I was taken aback at

this at first and could scarcely find words to reply to the nice complimentary

speech made by the C.O. but I eventually managed a few words of thanks. This

clock has to-day done considerable travelling and is still with the family.

In the days of which I am writing, Ayr

was considered a quiet country town where the custom of engaging farm servants

was a quaint one. Those requiring a change of job, together with the people

looking for new servants, would walk up and down the pavements, and when the

farmer saw a man or girl he thought would suit him, he would approach and

question the person, and if both suited each other, they then took hands to seal

a six month's contract. This was done twice yearly and occasion was called a

feeing fair. A set of shows and roundabouts were usually a big draw and the lads

from the barracks had a gay time with these farm lassies, with rides on the

merry-go-rounds at 1d. a time.

Sundays in Ayr were spent quietly, and

after church most folk would take a walk along the beach, down to Greenan Castle

and back - no boats ever putting out and all very quiet along the quay - until

one Sunday the officers decided to sail their boat, the Fusilier, on an outing.

I was called and asked to make up a box of sandwiches, etc. and a couple of

bottles and to find two others to form a crew. I went across to the sergeants

mess and had no difficulty in getting volunteers - everyone wanting to go - but

it was decided that Sam Love (Sergeant Major) and Sergeant Tam Stewart were the

winners, so together with Lieuts. George Mott, Feathersonhaugh and a civvy

friend, Gady Cunningham, off we went. We dragged the boat to the launching slip,

ambled aboard and pulled clear of several boats before hoisting the sails. There

was a comfortable light breeze blowing, which took us along very nicely, whilst

a small crowd of amazed townsfolk watched prophesying all sorts of disasters

happening to us breakers of the Sabbath. However, it looked and felt very fine,

gliding along easily, one or two trailing fishing lines. When we were about four

miles out there was a sudden darkening of the sky with a heavy wind that caused

us to lower the sails and sit waiting for it to slacken, but instead, the wind

grew stronger and we unstebbed the mast laying it along the boat, and tried to

use the two damaged oars. The rain now began to pelt down on us, and we tried to

cover ourselves with the canvas whilst the boat was carried with the wind at a

good pace, keeping parallel with the coast and giving us a feeling of safety as

long as we did not ship too much water. There was no more joking and I am sure

several were saying a little prayer.

Travelling along like this for about

seven miles brought us nearer to the coast, and after struggling hard with the

two oars, we reached a small fishing village called Dunure, seven or eight miles

from Ayr. There was no landing place nor could we get near enough to land, owing

to the jutting rocks. One man, Sam Love, a six foot inches warrior, decided to

enter the water, and seizing the prow of the boat, he guided it as near as he

could, but this left a gap of five yard to negotiate. The mast was lowered

across the gap and each in turn sat astride this and crept ashore, whilst

several fishermen stood watching us, hand in pockets and offering us no help. We

hauled the boat on to the beach and found later that only a few yards away was a

perfect "hard" for landing boats.

We made for the village post office but

found that no telephone operated on Sunday. The Postmistress, an elderly widow,

kindly offered us the use of her kitchen, where she soon had a huge log fire

burning in a big open grate. It was now about 7 p.m. and everyone was getting

hungry. I suddenly thought of the box which we had left in the boat locker. Tam

Stewart and I walked down to fetch it up, whilst two of the officers went out to

find a man who would ride to Ayr. The sandwiches and cake went down very well,

and the old lady made a dish of tea, each mug being laced with a liberal dose of

whisky. The two officers returned without having found anyone.

Now that we were all dry, we were

thinking of making plans for the night, when a knock sounded on the door and we

found a young farmer who had heard of our plight and had brought a horse with

him. He said that he was willing to gallop into Ayr with a message on payment of

a pound, so he was given a sovereign and a note to Gemmels, the car proprietors,

asking them to send for us as quickly as possible. The lad galloped off and at

11 p.m. we heard the rambling of wheels outside and found that they had sent a

private bus along. After thanking the old lady and promising not to forget her,

as she would not accept a gift of money, we said goodbye to her and set off for

home, arranging first with a man to bring the boat home when the weather was

favourable.

We reached the depot near 1 a.m. All

the lights in the barracks were burning, as they had considered us a total loss,

and police were still our searching the beach for our bodies. Gady Cunningham

was driven home to Belmont, the family estate, where he found Lady Cunningham,

his mother, sitting on the steps weeping. My wife, Aunt Mary with her, had

waited up, feeling confident that we would return, and had kept dinner waiting

the whole time. Without wasting any more time, we sat down to a very welcome

meal, both the sergeant-major and Sergeant Stewart being invited to take part.

At about 3 a.m. we ended a day which I am certain none who took part in will

ever forget.

A few months after, the sergeants' mess

outing was due to take place and it was customary to invite the married families

to this. On the recommendation of Sergeant-Major Love, it was decided to picnic

at Dunure, the spot where we had landed. We went by road in several horse drawn

charabancs, each with three horses, one leader and two in shaft. The drive out

was very enjoyable and after choosing a place on the rocks, we unpacked and

commenced to lay out everything ready for lunch, when with a suddenness no one

expected, it rained. We covered everything with table cloths, on top of which we

put tarpaulins, and then the heavens opened and it pelted down. We managed to

pack all the women and children into the school hall which had been handed over

to us for the day, but most of the men were drenched. During a slight break, we

rushed as much of the eatables over to the hall and served lunch there - but

imagine how disgusted my wife and I felt after having spent a whole week

preparing this lunch, only to see it eaten in this manner. Being wet to the

skin, however, I began to feel I did not care what happened.

My second visit to Dunure was worse

that the first. However, we had a good supply of liquor and this seemed to

compensate the men for the outward soaking we had had. It ceased raining at 4.30

p.m. and as most of the women were feeling miserable, it was decided to pack up,

which we did, saying good-bye to the place for ever. I have heard that many more

trips have since been made from the depot to this charming spot.

As I possessed all the necessary

certificates for promotion, earned in the Battalion, I was appointed

Lance-Sergeant a month before my first son, Tom, was born. Aunt Mary came from

Glasgow to help my wife with the work, bringing her two small girls "Georgie"

and Jessie with her. She stayed for two months. At the time she was with us, an

incident took place, that always caused a smile to appear afterwards. Recently

made a sergeant, I used to spend an occasional hour in the sergeants' mess, and

one night, when I was talking with the sergeant-major and two others, the

orderly sergeant closed the mess and it was understood by all that once the bar

was ordered to close, no more drinks could be served. My group was on the point

of ordering a round and was disappointed, but could do nothing about it. I then

suddenly remembered that in the officer's Ante Room every night there was a

Tantalus, holding bottles of whisky, gin and brandy, and there was also a case

of mineral waters. Looking through the window I could see the officers' mess was

closed and all lights out, so I suggested to the sergeant-major that we go over

and have our last one there. He thought that this was a fine idea. We were four,

the sergeant-major, Sam Love, the quartermaster-sergeant, Charlie Stevens,

"Whisky" Bob Smith and myself. We gained the mess, entered the back door and up

the half flight of stairs, into the Ante Room, all very, very quietly. The

officers' quarters were in rooms above the mess, and any noise could be plainly

heard. We all sat in easy chairs and I opened the Tantalus and served whisky all

round, thinking and hoping that that was to be the "one and only". But the talk

developed into an argument and other drinks were served, until they became

distinctly talkative. The orderly officer, who lived immediately above the Ante

Room heard some noise and dressed, buckled on his sword and went to the guard

room, returning with the sergeant of the guard and two men, all carrying rifles

and fixed bayonets.

The moment I heard him coming down

stairs, I put out the one gas burning, and appealed to the three for absolute

quiet. I threw off my jacket, and as he was about to enter, I met him at the

door, holding a chair that I had just moved. It was Lieut. George, one of the

crew of the shipwreck. He recognised me in the dark, and I explained that as my

waiter was on leave, I was doing a bit of cleaning in the Ante Room to help him.

He really had thought a burglary was taking place and dismissed the guard, said

good night to me and went upstairs. I could imagine the suspense of those

waiting inside and the fright they had received, were sufficient to sober them.

See what it meant - an all round Court Martial for being found drinking on

prohibited premises at 12.30 a.m.

I closed the door and explained to them

that we would have to use another door to get out, and to reach this they would

all have to get down on their hands and knees and with me leading, they would

have to follow me along the Ante Room, through the dining room, along a passage

and down some stairs, out into the barrack yard. Remember there was no light,

and the geography of the mess was completely unknown to any of them, but except

for an occasional bumped head, we negotiated our escape and I was very glad to

see them all on their way. The next day, the sergeant-major insisted on paying

for the bottle of whisky we had drunk, and gave me the four shillings to pay for

it.

My son Tom began to crawl about the

mess and became a worry to his mother and me, for we could scarcely keep him

penned in the small bed room we used, and most of his time was spent in the

kitchen, where he was taught all sorts of tricks by the mess servants. His

favourite spot was in a huge iron coal box kept below the stairs and most times

when he was missing he could be found half buried in coal and covered completely

with coal dust. It was in this state that I found him one day, sitting in the

middle of the Ante Room, when the bell rang and I went to answer it. What a

sight met my eyes! Tom sitting there, enjoying his surroundings and four or five

officers roaring with laughter, one officer remarking to me as I entered "Good

God, Sergeant Groves, what is that!" I picked Tom up and put him under my arm

and said "This is my big son Sir," and took him down stairs, handing him over to

his mum who gave him a spanking and a good wash, but we never completely cured

him of his love of coal.

A bygone era

Bareilly, India,

early 1900's. Seated middle row, centre, is my grandmother, Janet Lawson Groves

(née Wyllie), born Ayr, Scotland; A photograph depicting the three eldest

children of Edward and Janet Lawson Groves, namely Thomas, Margaret and George

Groves.

[Historical:]

[Groves

Genealogy researched]

[Researching

Ed Groves - grandfather]

[Birthplace of Edward Archibald

Groves - father]

[Alnwick Newspaper extracts of 1916]

[Alnwick Camp

photographs]

[Lesbury

- a Groves connection]

Links to other websites:

|