As recent archaeological work on Egypt's ancient western frontier has pushed forward our understanding of Late Bronze Age activity in the region, it is starting to become apparent that the settlements found there did not serve just to protect Egyptian territory from hostile incursions. Whilst there is little room for doubt that the ancient settlements at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham and Kom el-Abqa'in possessed a military/defensive function, they may also have facilitated domination over region through socio-economic controls.

In this section, we will consider all aspects of the function of the fortresses.

There is no evidence to indicate that any fortifications protected Egypt's western border before the time of Ramesses II. There were occasional Libyan raids before this but nothing that appears to have caused any great concern to the Pharaohs. Why then did defences become necessary?

In the past, it has been assumed that it was either a response to increasing hostility from the Libyans or the "Sea Peoples", or indeed both. Whilst both groups were becoming troublesome, a closer examination of the evidence, outlined below, tends to suggest that perhaps the Libyans, more specifically the Rebu and the Meshwesh groups, should be considered the greater threat.

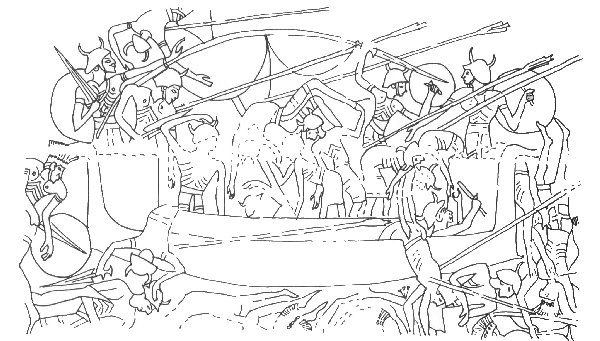

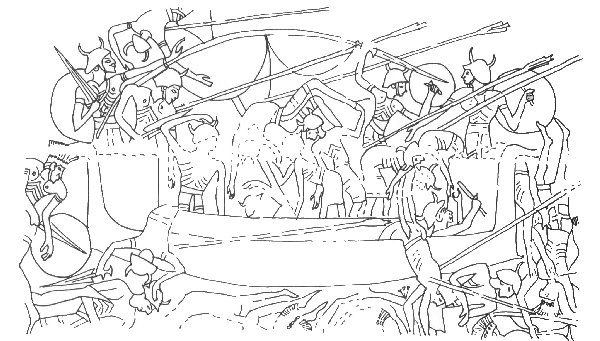

"Sea Peoples" is a generic term that is applied today to a number of groups of uncertain origin who caused great disruption around the eastern Mediterranean in the Late Bronze Age. It has been suggested that some of them may have originated in the Aegean islands, coastal Anatolia or even beyond (Redford 1992:243-245; Yurco 1999:720). Some of the earliest references to them are in the Amarna Letters of the early 14th century BC (Moran 1992:150-151, 201-202), where one of the "Sea Peoples", the Sherden, appear as pirates undertaking coastal raids. By the reign of Ramesses III this had developed into large-scale movements of population, a virtual mass migration into Egyptian territory (Peden 1994:23-36; Yurco 1999:718, 720). The reasons for this movement are not really understood. It has been suggested that famine in their homelands may have forced the inhabitants to seek out new sources of food, in the fertile Nile Valley for example, or that a weakening in the political control exercised by the Late Bronze Age powers over the northern Mediterranean was exploited by their former vassals who attempted to expand their interests (Redford 1992:244-247; Yurco 1999:720).

Perhaps a significant event with regard to the issues at hand here was a raid by the Sherden upon Egypt early in the reign of Ramesses II, recorded upon the Aswan Stela (Kitchen 1996:181-182). The details of the raid are sketchy but it is apparent that they were causing disruption in the Delta region.

There were two principal routes by which these raiders could have arrived at the Delta. One was from the west, coming from the Aegean and along the North African coast, the other was from the east via the western coast of the Levant (Redford 1992:247). Both of these were active trade routes in the period (Cline 1994:91-93; Watrous 1992:176-177). However, the eastern approach to the Delta was protected by the fortresses of the "Ways of Horus" (see maps here or click here for more details) so perhaps a western approach was preferable. If this was indeed the route used, maybe this convinced Ramesses II that a similar chain of defences was needed to the west to prevent any further Sherden raids.

However, if the "Sea Peoples" were being targeted by the coastal fortresses, the evidence so far uncovered has revealed nothing to confirm this. Also, the threat posed by the "Sea Peoples" may not have actually been that great. This is suggested by Merenptah's Karnak inscriptions that record the attempted invasion of Egypt by the Rebu-"Sea Peoples" alliance, where the latter group appears to have made up only around 25% of the invasion force (O'Connor 1990:41).

Perhaps a better indicator that they were not a significant danger in their own right is the suggestion that the "Sea Peoples" may have been under the control of the Rebu leader, perhaps even in his service as mercenaries (O'Connor 1983:276; 1990:93). This might fit in with the idea that they were only a relatively small force and that at this point they were not a great threat on their own.

Whilst the evidence to link the "Sea Peoples" and the construction of the fortifications is limited, there is a certain amount that points to the Libyans as having been their real target.