SumerianValuesMeanings.htm

Sumerian Signs: Values and Meanings

by Patrick C. Ryan

(6/1/2005)

(6/1/2005)

All available readings for Sumerian signs in

Kurt Jaritz' Schriftarchäologie der altmesopotamischen Kultur (1967) are listed in the Sumerian Sign Value Register.

In this register, all readings associated with a particular sign can be found

by doing a search for the sign number: e.g., to find what other values are associated with the sign reading bur, first find bur in the register; note the sign number, which is 646; then do a search for 646;

bur and the two other readings associated with this sign (biS [biš] and pur) will be found.

In addition, many compound signs utilizing 646 as a component will be revealed but not all since Jaritz designated with one number some signs that are easily analyzable as compounds of two or more signs; e.g. lugal, which appears as sign 280 is a clear composition of 640, gal over 611, lu2.

To find an archaic sign form, where available through the courtesy of Dr. Antonio Reguera Feo, simply search for the sign reading, e.g. bur; note the sign number (646), press here or below to display the Sumerian Archaic Sign Table file; find the sign number in its tables. If highlighted, a picture of the sign

will appear on the screen when the number is pressed.

To facilitate searches, several notational conventions have been employed:

1) g and g~ (g with a superscript tilde) have both been rendered as g.

2) š has been rendered as S;

3) /?/, emphatic s and t, and back k, which are not currently recognized by Sumerologists but were notated by Jaritz as ', s and t with subscript dots, and q have been rendered as ', s. and T, and q.

Current Sumerological practice is to distinguish homophonous words by accents or subscripted numbers beginning with 4 in the order of frequency of usage. The commonest homophone is indicated by no subscript, which is followed here. The next two commonest homophones are indicated by acute and grave accents on the final vowel, e.g. dá, which will be rendered here as da2 and dŕ, which will be rendered in the above documents as da3 but in this essay as da3.

Determining Phonetic Values (Readings) for Sumerian Signs Associated With Certain Meanings

Sign #1 , which in later cuneiform is a simple horizontal stroke with a wedge (cuneus) on its left side, is a descendent of, at least, two archaic Sumerian signs. The first, shown at the left, it will be noticed, is a simple vertical line (SSAsh-1-1.jpg at this website).

Sign #1 , which in later cuneiform is a simple horizontal stroke with a wedge (cuneus) on its left side, is a descendent of, at least, two archaic Sumerian signs. The first, shown at the left, it will be noticed, is a simple vertical line (SSAsh-1-1.jpg at this website).

Sumerian was most commonly written in vertical columns, from top to bottom, which ran from right to left.

The Semites, who painfully adopted it, preferred to read horizontally rather than vertically, and turned the tablets 90° to the left, with the result that the tops of the Sumerian signs were leftmost on the horizontal line. This also resulted in a forced reading from left to right (in the Semitic languages Assyrian and Babylonian) as opposed to the Sumerian practice of reading from right to left. This surely has some ethnic or cultural significance. Modern Semitic languages write from right to left; and this is the preferred direction to read for hieroglyphic Egyptian when written horizontally.

Replacing pictures of common objects with cuneiform wedges and strokes and orienting them differently means that cuneiform is, with greatest difficulty, to be used in determining the original nature of the representation, which, we shall see, is a key to its phonetic and semasiological origin.

The second recovered Urform is illustrated above.

For both of the two archaic forms, Kurt Jaritz' in Schriftarchäologie der altmesopotamischen Kultur has 26 recovered readings:

ana3, as/z3, aš, aša, ašša, dal3, di/el(i/e), di/eš2, ge15, gubru2, hil2, in3, ina, makkaš2, ru3,

rum, sagtag, salugub, santak, simed, šup3, tal3, ti5, til4, Til, ubu, utak;

probably several more have not survived. The underlined entries in the list can be identified with meanings; those in italics, cannot be assigned a meaning at this time. These latter ones will not be considered in the discussion that follows except to show how they phonologically might have been attached to the sign..

The major meanings recorded (as found in my Sumerian Glossary) or other published sources are (the asterisk indicates an additional treatment of the word below):

*ana3,

(this) one

*aš, ‘one; unique'

*aš, ‘spider'

*aša, ‘one, unique'

*ašša, ‘noise'

*dal3, ‘*dividing line' (deduced from dal [#132])

*de/il(e/i), ‘one; single; only; alone; unique'

*de/iš2, ‘one'

*makkaš2, ‘wailing; clamor'

*ru3, ‘be equal in size or rank'

*rum, ‘perfect, ideal'

*sa(n)g[~]3tag (for sagtag), pillow (?); wedge; triangle

*tal3, ‘noise'

*til4, ‘cry, shout, scream'

For the following, the meaning is unknown: *as/z3, *ge15, gubru2, hil2, *in3, *ina, salugub, *santak, simed, šup3, ti5, Til, ubu, utak.

DISCUSSION

It is the assumption of this writer that the earliest system for both the choice of sign employed and the word value assigned were semasiologically simple and elegant through the graphic employed.

At the basic level, we can identify this as a ‘scratch' on something - before we begin to interpret its abstract meaning.

It is the assumption of this writer that Sumerian had three major verbal formants for producing what, at first, were grammatical distinctions in roots; though later, the resulting combinations of monosyllabic root + formant were, to some extent, lexicalized.

The first formant was -i, the Sumerian reflex of PL

?E, which, with verbs, formed a progressive aspect (transitive) or durative aspect (intransitive) verbs. It is, in and of itself, not a marker of a plural Aktionsart, for which numerous other formants existed. Rather, its affect, with verbs, is to create a participle which, at an early date, syntactically attached the verbal action directly to its agent, thereby subordinating it. In its absence, and without other formants, the verbal root conveys punctual verbal action. It is also used with nouns to differentiate between related usages, and to form adjectives from nouns, which were usually lexicalized; e.g. ?A-?E-NA, ‘top+like=top-like+one' for Sumerian en, ‘lord'. The sign, Jaritz #161, depicts a ‘building with several short lines running up from the roof directing the focus of interest'. This word (Sumerian *ęn (written en) can be seen again in Old Indian iná-H, ‘commander' (derived from Pokorny's 3. *ai-, ‘overpower' [‘be on top']).

In Sumerian, the basic underlying form without -n (‘one') was lexicalized as ę2 (written e2), ‘house' from ‘roof' (‘what is top-like/on top'; Jaritz sign #599 depicts a ‘flat-roofed house with the focus on the roof indicated by a vertical line').

The full cited form is en/i/u, which will be significant in a few paragraphs below. It also means ‘to watch', i.e. ‘to be in charge over', ‘over(see)'; I believe that as a verb only does this sign have the additional values of eni or enu (again, see below; we will see that they represent the verbal root + the formants -i and -u).

In PIE, this first formant (PL ?E) is represented by *y, and forms countless stems in -y from verbal roots: e.g. *g^hrey-, ‘shining', from *g^her-, ‘shine'; as -*i: (an unstress-accented form from -yo), it differentiates feminine from masculine nouns among other functions; and forms adjectives with -i from nouns. It is known also as a suffix forming verbal adjectives with the meaning of passive participles or participles of necessity as well as simple active or passive participles.

In Egyptian, -j is a very common formant. It occurs in many verbs that, by Egyptologists, are termed ‘final infirm', of the form CVC(V)j and CVCVC (V)j. In the first case, they are not currently considered a stem of a biliteral root but rather a part of a triliteral root ending in a ‘weak' consonant. In the second case, although the suffixal nature of the final j is generally recognized, no successful attempt at assigning a meaning to the suffix has been attempted to my knowledge. The fact, however, that it occurs in triliteral roots (since quadriliteral roots are practically out of the question), leads me to believe that it is also a suffix in, at least, some biliteral roots; additionally, the purported suffix is not always indicated in writing, further suggesting to me that we are not dealing with defective writings but rather biliteral roots suffixed with j in their uncompounded root form.

In Sumerian, we find traces of this formant in the multiple consonantally related values of some Sumerian signs (differing only by vowel quality) so that, in the absence of lexicalization, all three results from the combination of the monosyllabic root + common formant are available for the one sign. Thus, any monosyllabic root of the form Ca could remain uncompounded;

or could generate a progressive with -i of the form Cę (written Ce in our present transcription), representing earlier *Cai;

a frequentative with -u of the form CU (i.e. C + /o:/, written Cu in our present transcription), representing earlier *Cau;

and finally a stative with -?a of the form Câ (i.e. C +/a:/ but possibly C + /a?/, written Ca in our present transcription), representing earlier *Ca?.

It is fairly probable that these formants did not attract the stress-accent in monosyllables.

It is, at once, obvious that we cannot distinguish between most simple uncompounded roots ending naturally in i, a, and u, and roots compounded by the stative or frequentative formants in monosyllables because in the writing, short and long vowels are not distinguished. However, if we can determine an uncompounded form Ca of an originally monosyllabic root that sign shows alternate readings of Ce/i and Cu, with the same or closely related meanings, we can regard them as a strong support for this hypothesis.

With Sumerian CVC roots or former CVC roots as in the case of en, ‘to watch', discussed briefly above, the stress-accent on the original first syllable has removed any trace of the earlier final vowel of the second syllable.

Accordingly, I emend the forms above to ęn for the simple uncompounded root; ęn-i (for recorded eni), a progessive/durative stem; and ęn-u (for recorded enu, the frequentative stem.

In originally ‘CVCV compounds, which have been reduced to CVC by the stress-accent, an alternate reading with CVC+vowel can indicate the use of a stem formant. An example which can be cited is gub/p / gub/pa (for gu'b/p+a) / gub/pu (for gu'b/p+u), all of which are readings for Jaritz sign #410, which, as can be seen, portrays ‘a lower (possibly right) leg and foot'. This verb, uncompounded, means ‘stands up' (punctual); gub/pa is the root + the stative formant PL

?A, meaning ‘standing'; gub/pu is the root + the frequentative formant PL

FA, meaning ‘stands around'. If the form *gub/pi had been recorded, it would mean ‘is standing up', with some implication of duration or possible non-completion.

As an aside, this same sign (Jaritz #410) has a recorded reading of kub/p; and under the recorded reading of gub/p, a recorded meaning of ‘characteristic of sheep or goats'. One of the major characteristics of sheep and goats is the cloven hoof. PL 'KXHO-P?FE would mean ‘cut-foot/toe'; and by the

rules of conversion we have developed, would result in Sumerian first *'kub/pi then kub/p, with elision of the final vowel through the affect of the stress-accent: . I feel confident the reading of gub/p for the meaning ‘characteristic of sheep or goats' (‘cloven hoof') should be emended to kup. The predicted Egyptian reflex *xb is not recorded for ‘cloven hoof'. The PIE evidence is problematical but *k^o:/opho-, ‘hoof', can be noticed, as well as keub-, ‘hoof', which seems related to Sumerian hűb2, ‘foot(1)' (PL KHO-FHA-‘P?FA, ‘cover' + repeatedly + ‘prominent' = ‘hoof', perhaps, by extension: ‘sandal'); cf Egyptian Tbw, ‘sole of foot' (if for *Twb); *Tbw.t, ‘sole of foot, sandal' (if for *Twb.t) .

In addition, there is PIE *keubh- meaning ‘stand out, rise up' (Old Indian reduplicated kakubhá-), which probably is to be connected with gub/p (possibly PL K?O-‘FA-P?FO, ‘bow back' + repeatedly +'leg' = ‘straighten leg' = ‘stand up'?, which could yield *gűp), ‘stand'. In this context, we might also notice Egyptian TbTb, ‘hoist'; this is attested late, and may formerly have contained an unwritten medial w; or, perhaps, at least some PIE stems (formerly with original medial *o-) have been re-patterned for differentiation from other phonetically similar stems with medial -*w-.

The Sumerian Verb

Every Sumerian verb is recognized to have two major forms: hamTu, which can briefly termed punctual, i.e., representing the verbal idea as a single act (equivalent to nominal ‘singular'); in the case of gub/p, with a singular subject, this means ‘stands/stood/will stand'. The second form is called by Sumerologists marű, which can be briefly termed durative, representing the verbal idea as a number of acts (equivalent to nominal ‘plural').

Sumerologists have conflated a number of different inflections under the rubric marű that need to be distinguished:

1. Transitive

a) In any transitive verb construction, the completion of the idea of the verbal action, which produces a permanent affect, is the ultimate goal of the action. In Sumerian as in other related languages (PIE and Egyptian), this is most easily marked by verbal complete reduplication: gul, ‘destroy', i.e. ‘performs an act leading to total destruction of'; 'gul-gul, ‘accomplishes the act of total destruction of'. This type of reduplication is recognized by Sumerologists as ‘emphatic reduplication' and by PIEists as well; and it is equivalent to nominal complete reduplication in Sumerian: kur-kur, ‘all the foreign countries', from kur, ‘foreign country'.

a)) Complete reduplication has been accepted in Sumerian as a method to mark ‘repeated acts without the implication of achieving the ultimate goal of the verbal action'; in other words, it is considered a category of marű reduplication.

a))) Thomsen (1984: 304), in my opinion, incorrectly lists gul-gul as a marű form of gul, ‘destroy', citing the phrase: ". . . e3 gul-gul-lu-de3 . . .", . . . (that its) house(s) shall be destroyed . . .". We analyze this differently, as an emphatic reduplication: gul-gul-, ‘utterly destroy'; (-l-)-u-, frequentative; -d-, future; -e(3), ‘for' (see below)(2).

b)) N.B. Every Sumerian verb can have a causative use without any special marker of an intransitive verb, which, usually makes them transitive: gub/p, ‘stand'; a recorded meaning for gub/p is also ‘build, erect', i.e. ‘cause to stand'. Without the expression of an ergative subject, the same verb used transitively without any special marker can be passive: gub/p, ‘is built/is caused to stand'.

b) Incomplete or partial reduplication in Sumerian is a well-established method also used in PIE and Egyptian (in the last, through doubling of the final radical of the root) to mark ‘repeated acts without the implication of achieving the ultimate goal of the verbal action'. In Sumerian, it is termed marű (partial) reduplication.

a)) We find partial reduplication of the basic verb as the marű form listed by Thomsen for kur9 (hamTu); ku4-ku4 (marű); ‘enter'; both are written with the same sign; i.e. they are both recorded readings of the same sign (Jaritz #99, derived from one of four archaic signs rhat depicts a ‘sprout coming out of a hole' or ‘being tall in a hole'). In order to fully understand all the ramifications of the situation, we must look at both the hamTu and marű manifestations of this verb.

a))) An example is the (hamTu) phrase rendered by Thomsen (1984:142) as:

g~a-e i3-ku4-re-en

'I entered'

In the hamTu third person singular, Thomsen has:

a-ne i3-ku4

'he entered'

Why should the final -r of the verb, which is resumed by -re- in the first two persons of the singular, disappear in the third person? In other words, why is this not read kur9 for the third person singular? Does Sumerian not have enough homonyms as it is? Some Sumerologists have theorized that many final consonants are subject to deletion if not followed by a vowel as a part of an inflection added to the verbal root. Even Thomsen seems skeptical of this when she writes: "As a rule, we may perhaps presume (emphasis added) that the final consonant of a verbal stem is dropped in the marű reduplication. . .". And this is a cautious restatement of a principle that other Sumerologists have taken farther with, for example, the third person singular form cited above.

I think there is a better explanation (that allows the integrity of the verbal root to be maintained) than that of this final consonant being elided if no voweled inflection follows.

I propose that the third person singular hamTu form should be read:

a-ne i3-kur9

'he entered'

First, let us remember that the reading ku4 is justified on theoretical grounds alone. If we operate under different premises, and propose, as we have, a reading of kur9, the signs would be exactly the same.

I propose as a counter-theory that the reason the final consonant is resumed in the first and second singular forms (as well as throughout the plural) is not to indicate retention of the final consonant of the root which would otherwise be elided but rather >u>to indicate a shift of the stress-accent to the second syllable:

g~a-e i3-kur9-‘re-en

'I entered'

One of the reasons that has been advanced by the proponents of the ‘disappearing final consonant' theory is that, in this verb, the marű form is a reduplication: written kur9-kur9. In marű forms with inflection, however, the final consonant is not resumed, hence, must have been elided:

g~a-e i3-ku4-ku4-en

'I enter'

The better explanation, in my opinion, is that Sumerian followed a pattern of reduplication known from PIE, namely that the first element of the reduplication receives the stress-accent: ‘kur9-kur9; and, as in the case of normal (non-emphatic) PIE reduplication, the final consonant of the first reduplicated root is rarely retained but, in verbs, generally elided: this would yield ‘ku4-kur9. That this was true of Sumerian as well is suggested strongly by the transcription babbar, ‘(being) white', for what we think we know is the result of a partial reduplication(rather than assimilation) : *barbar, presumably a reduplication of *bar11, ‘*white', another reading for the same sign (Jaritz #684). Now, it is always possible that this is an emphatic, complete reduplication, and that the missing final -r and presumed gemination for the b is a result of assimilation rather than elision; if this is true, the form suggests a stress-accent displaced to the second syllable.

The proposed, new reading of the first reduplicated sign kur9 has the advantage of explaining how the same sign came to be read ku4 as well as kur9; it would be the actual reading of the first element in a partial reduplication, with the sign retained to provide semantic continuity. Interestingly, as mentioned above, intensive reduplication is usually a complete reduplication as has been proposed for Sumerian, and is also known for PIE; and can be theorized for Egyptian (ex. sk.j, ‘destroying [‘is causing to perish']'; sksk, ‘[probably ‘utterly'] destroy'; sk.j, ‘is perishing [‘is being wiped off']', is probably a durative passive derivation from sk (3), ‘ wipes off [‘to dry']'). For anyone who believes that this development of meaning is strained, consider the usage of ‘liquidation' and ‘eradication' in modern English - being ‘liquified' or ‘erased' is quite a fatally serious matter.

If this analysis is correct, the reason the final consonant is not resumed in the marű reduplicated form is that the stress-accent, which, uninflected is on the first syllable, only shifts to the second syllable when combined with a voweled inflection (and not to the third syllable); consequently, final consonant resumption for the third syllable is inappropriate:

g~a-e i3-ku4-‘kur9-en

'I enter'

While in the third person singular, the reduplication, by itself, indicates a stress-accent on the first syllable so that no other stress-accent marker is necessary:

a-ne i3-‘ku4-kur9

'he enters'

In the oldest recorded Sumerian, the third person singular of the marű form for non-reduplicating verbs shows -e with resumption of the final consonant of transitive CVC verbs: -sar-re, ‘he writes'. The indication we have from later Sumerian is that object elements, if present, precede the verbal root in a transitive employment of the verb (i(-)b2-sar-re. Accordingly, at least in this third person singular form, we can assume that, in the absence of the reduplication to indicate marű, i.e. this element (-e) indicates it. If my analysis of the vowels in Sumerian is correct, e can only occur as a reduction of the diphthong ai, a rather common phenomenon in the languages of the world. We further assume that, because of its derivation from a diphthong, that e is long, i.e. *ę, and can only be long. In originally CVCV nouns and verbs which bear the stress-accent on the first syllable, any trace of the final short vowel has disappeared. Further supporting this view is the fact that the final consonant is resumed, which we, above, assigned to an indication of a shift of the stress-accent to a non-initial syllable: thus sar-re represents *sar-‘rę; the long vowel has drawn the stress-accent from the first syllable. The PL monosyllable which seems the likeliest candidate for contributing an *a to the diphthong is HA, which we believe signified a large indefinite animate plural. If our assignment is correct, this would result in /a:/, the same formant we see in PIE collectives in -a:. This Sumerian *â could only be written a since Sumerian possessed no recognizable mechanism for distinguishing long vowels from short vowels (there is always the possibility that long vowels could be indicated by sign selection but this is difficult in extremis to demonstrate). It was, therefore liable to be confused with ?a or later â (both written a), a suffix indicating the locative from PL ?A, i.e. ‘top' becomes ‘on'. While the locative maintained its form, to differentiate it from the large indefinite animate plural designating the marű inflection, the marű inflection was modified by adding i, resulting in the *ai mentioned above which became *ę. Because its meaning was roughly ‘many(-like)', it was admirably suited to be employed as the plural personal inflections of any verb.

On the other hand, we find -e as a suffix in the first two persons of the singular of the hamTu and marű forms of intransitive verbs, where any indication of the subject is placed after the verb while the third person has no suffix. There is no justification for a plural element in the singular so this -e must have a different origin. We can see better what it represents if we know that in the oldest Sumerian, ‘he' as an ergative subject was a-ne; it became e-ne in later Sumerian; and the rare use of a demonstrative -e is attested that means ‘this'. What seems to me likeliest to conclude is that in a-ne, the first syllable represent PL ?A, here interpreted as ‘here' so that a-n is ‘this one' (the second element is PL NA, ‘one'; and that in later Sumerian, this element, a was combined with i, ‘-like', to produce *ę, written e, i.e. ‘here(-like)', corresponding to the demonstrative e. In the first two persons of the singular, then, the suffix -e designates the first and second persons as ‘here', i.e. participants in the conversation (without distinguishing farther between them), opposing the third person, which, also bears -e if the verb is not reduplicated to show the plurality of the verbal idea in the third person singular transitive marű.

Thus, only a later misunderstanding of the logic of the system could result in the addition of -e to a reduplicated third person singular in any of the verbal categories since the plurality of the verbal idea was already contained in the reduplication; and the third person singular was not a part of the speech situation; and, being singular, indicating the plural nature of the subject was not appropriate; The -e would be mandatory in any third person singular marű that was not reduplicated; and unnecessary in any third person singular hamTu form. With the phonological identity of these two elements (speech situation and verbal plurality), it is hardly to be wondered that later scribes were inconsistent. In the first two persons plural of unreduplicated marű verbs, both the verbal plurality e and the speech situation e would have been theoretically called for but if both were employed, that employment is invisible since they apparently coalesced as e. This is probably the reason why, after Old Sumerian, unreduplicated marű verbs added -n to the first and second singular as well as plural in an attempt to mark the speech situation (conversation participants) in addition to the- e marking verbal plurality.

Two final elements may be mentioned for the sake of completeness. In the third person plural of transitive marű verbs, in the final position of the inflection which theoretically called for a marker of speech participation, a marker to indicate plurality for the ergative subject was added. The nominal plural -e-ne (‘many-animate subject-ergative') termination, which was abbreviated to -ne was borrowed and employed so that the combined inflection became -e (verbal plurality) + -ne = -e-ne (ergative subject plurality) for unreduplicated verbs. For those with reduplication, only -ne was necessary.

For transitive hamTu verbs, in the third person plural, a prefix indicated the ergative subject (i(-)n-zig-). In the next to final position of the inflection, which theoretically called for a marker of plurality of the subject, that was indicated by -e-. In the final position which called for a marker of object plurality, the inanimate nominal plural suffix seen combined with me, ‘to be', in -me-eš was employed. This -eš is related to aš, ‘one, unique', (probably ‘those unique ones'), mentioned above. The idea seems to be that individual inanimate objects are being contemplated. This e and eš combine into -eš.

For intransitives, both hamTu and marű, in the inflection for the third person plural, we expect, a marker for subject plurality in addition to a marker of verbal plurality, either in the form of reduplication or e for the marű forms. The marker we find in this position is surprising: -eš. This marker, eš, as mentioned above, is essentially inanimate, and intrinsically unsuited to convey the plurality of an animate subject for an intransitive verb. The only possible reason I can think of for its use here is to differentiate between intransitive verbs inflections and the inflection of the third person plural of the transitive marű verb. In any case, we have -eš , which represents either e + eš = -eš or simply eš. The -eš of the oldest inscriptions is -eš2.

In later Sumerian, additional pronominal elements which were not present in oldest Sumerian apparently, were employed to differentiate the first (de3) and second persons (ze2) of the plural but though they are inferred for older Sumerian, they are not attested, and beyond the scope of our discussion. Later yet, -en was added to these elements, presumably representing an abbreviated form of -e-ne, ‘nominal animate plural.

c) And finally, some verbs, termed regular, form their marű modification purely through inflectional means:

a)) An example is gub/p (*gűp); with a singular subject, the hamTu form means ‘stands up/stood up/will stand up', as mentioned above; the marű form means ‘is standing/was standing/will be standing', or gub/'p+u (written gubu with one sign, Jaritz #410; also recorded: guba). It is important to note that this inflection can only be seen through recorded variants of the sign since final short vowels are not indicated in the system, and when the inflected verb is followed by additional elements: e.g. gu'b/pu, which yields gu'b/pun, written gu'b/p(u)-b/pu-un. To be explicit, bu has the recorded variant pu.

Current Sumerological theory explains the u of b/pu and the following -un as a consequence of the root originally containing a final u, to which the familiar -en is assimilated. This is certainly possible. But what militates against it is the existence of the reading gub/pa. The simplest explanation, I believe, is that this verb had the basic form *gűp, and that the readings with u and a represents stem formants in the form we should expect from PL FA/FHA (frequentative) and ?A/HA (stative). Since the great majority of verb forms in Sumerian are third person singular, we could tell only from the context if a stative *gű'pa were to be read, something along the lines of ‘the temple stands', with a condition implied. But the stative is also very suitable for what Thomsen calls "subordinate construction". The verbal root + a is used in constructions like the following:

Utu e2-a, ‘the rising sun' (‘the risen sun'?)

inim dug4-ga, ‘the spoken word'

This, I believe, represents the stative since Sumerian has no discernable trace of a past or passive participle. Even when an ergative subject is included, the verb form is prefixed neither by i-, which is a particle meaning ‘then' (PIE e-; Egyptian j-), or a subject element (-n-) for a transitive verb). This is because no transitivity is associated with a stative except parenthetically. The frequentative describes an action that is repeated until a contemplation completion; the stative represents the state or condition achieved without reference to the preceding action,

The stative in Egyptian cannot, with certainty, be identified because the sign with which ?A/HA would be written, the REED-LEAF (j), also represents ?E (which became /y/: a durative formant), HE, and żA/HHA; as well as żE/HHE. However, the REED-LEAF occurs in a situation where a stative is to be expected most naturally, to form verbs from adjectives: nfr, ‘beautiful'; nfr.j, ‘to be beautiful'.

In PIE, the stative is present but not very obviously. First, it is present as a stem formant, mentioned, e.g. by Robert S. P. Beekes on page 230 of his excellent book, Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction (1995): "d. Suffix eh1 - This suffix served to express a situation . . .", i.e. a state; and he quotes forms which mean ‘to lie' (‘be prone'). Interestingly, even Beekes misses other examples of this stative suffix, without e, e.g. wemh1-, ‘vomit', where the phonological result of both is e in Greek eméo: and Latin jaceo:, ‘I lie'. The PIE response to PL ?A could be either /a:/ in certain positions or /a/, which would have become like all short vowels *e/o. The PIE perfect is very close in meaning to a stative. Based on Greek oîde, ‘he knows (he is knowledgeable of')', the third person singular has been reconstructed as the simple -*e; this is supported by Hittite (*-i-). On the other hand, the second person plural is reconstructed *(h1)é, the stress-accent being a result of stress-accentiation of all the plural forms. From the actual recorded data, this could as easily be a; or be e derived from stress-unaccented *a.

Accordingly, I propose that the earliest perfect inflection in PIE was a stative in *?a which is preserved in the first person singular of Greek oîda, ‘I know (I am knowledgeable of')' and in the second person plural of Sanskrit vidá as well as in the Greek and Sanskrit second person singulars oîstha and véttha. I also propose that the underlying form of the Sanskrit first and third person singulars forms was *wóida (earlier *wóidHa). The Greek form of the third person, oîde, will there not be a response to phonological antecedents but rather a secondary change instituted to differentiate the first and second person singular. Therefore, Beekes should have reconstructed *h2 throughout the paradigm wherever this, I believe, stative formant was employed, namely in the third person singular and second person plural.

We have referred several times to the frequentative, which shows up in Sumerian as u, and manifests itself in Egyptian and PIE as w and *w.

a)) In PIE, *-w is a very common second element of biconsonantal roots, matched roughly in number by roots in *-y and roots having *-e:, which, of course, it most often the result of an unspecified ‘laryngeal', so we could rewrite the third instance as *-H, the *e: only being the effect of the final ‘laryngeal' on the basic Ablaut *-e.

The very great majority of roots of the forms *CVw-, *CVy, and *CVH are related as frequentative, durative, and stative forms of a monosyllabic verbal root *CV (*CŘ/e/o), which has passed out of use in its simple unformanted form. The fact that PIE *V represents a former e, a, or o, means that, at least, theoretically three roots with different meanings are potentially masked behind every one of the formanted forms. And, since PIE came to regard *CVC as the canonical root form, these combinations have been lexicalized, and, in the absence of a recognition of their interrelationships, gradually diverged by broadening their semantic range so that the original common semantic basis modified by the formants has become more and more difficult to recognize. Yet, we will look at one such monosyllabic root to see if we can recognize it in these three major stems.

With CVC roots not containing these formants as the final *C, *-w, *-y, and *-H are considered suffixes that modify the root meanings by forming adjectives or nominal and verbal inflections although, as we saw above, -*H and *-y are recognized as forming new stems as well.

With *-w, we find that it has not yet been recognized as a stem formant by PIEists. However, it is recognized as a verbal inflection. Beekes identifies it on page 251 where he characterizes it as a verbal adjective in *-wo: e.g. Sanskrit pakvá-, ‘cooked'; this is not a participle simply describing a past activity but rather portrays the action as being repeated a sufficient number of times that the objective of the action has been realized. And, on one level, *-y can be categorized as ‘imperfective' against *-w, ‘perfective', and *-H, ‘stative'. This formant is also found in the perfect active participle ending *-wes, a combination of PL FA/FHA, ‘frequentative/perfective' + PL SHA, which designates a nominal state or condition; thus *-wes informs us that an action has been repeated a sufficient number of times that the goal of the action has been reach, and that the result of the action persists; in short, an active, perfective participle.

We can now undertake an attempt to show the interrelationships of ancient *CV roots to their stems in *-y, *-H, and *-w, which have been lexicalized.

Perhaps we should look first at PL T?E, which produces PIE *dŘ/e/o-. The basic nominal meaning is ‘heel'; the basic verbal meaning is ‘spin around'. Let us see if we can find corresponding *CVC roots in PIE. Since the stative form would appear first, which we would expect to be *de:-, we look at Pokorny's *de:-, ‘bind', which appears to be a causative of ‘spin around', i.e. ‘cause to be spun around, wrap around'. Accordingly, we would emend this root to the form pre-PIE *deH-. Readers will note I have attached no subscript to the ‘laryngeal'; this is because I do not subscribe to the theory of ‘coloring' ‘laryngeals'. I believe that the phonetic reality of the ‘laryngeals' was realized as /?/ and /h/; and that their principal effects were to lengthen and thereby preserve the quality of the original pre-PIE vowels.

br>

The stative form can be seen best in *dé:-mN-, ‘band'; and the stative nature of the root is confirmed by the fact that as an active verb, the root requires a formant: Old Indian dyáti, ‘binds' (*de:y-). There are no instances of schwa + /y/ in IE. That sequence is realized as consonantal /H/ + /i/, i.e. *dH(1)i-é-ti. The Old Indian form looks, at first glance, as if it were derived **d(e)yéti.

The Sumerian form we would anticipate to correspond with pre-PIE *deH-y- (from PL T?E-?A-?E), ‘bind', is *dî but what we actually find recorded is te, ‘bind'. Sign #680, which is used for this reading and meaning, depicts a ‘dam' or ‘barrier' of some sort (which the sign clearly depicts), which was bound together; and this sign has another reading of de4. We have already discussed at length the seemingly arbitrary variation between e and i as well as b d g and p t k; and therefore we emend te to *dîx, ‘bind'. Without the durative formant, we would have had *dix, ‘spun around, bound'. It is probably this form we see in the compound d/ti(-)men(-)na, ‘foundation' (possibly, ‘what is wrapped around = the band of the building?' if from men3/*minx, ‘*erection', a proposed meaning derived by me from sign #410 which has this reading, and PIE *1. men-, ‘range upward'. The similarity to *dé:-mN- I consider purely coincidental.

A PIE form with the formant -y (durative) can also easily be found as *2. dey6-, ‘whirl around, hurry', an intransitive employment. It can be seen in dí:yati, ‘he flies, hovers'. I speculate that the idea behind ‘hurry' is having the feet temporarily of the ground but it might be as simple as the speed normally implied by ‘whirl. In any case, we must also consider the final schwa as an addition of a ‘laryngeal' to a CVC root, namely **dey-. The form actually attested IN IE probably represents PL T?E-?E-HA, the animate stative as the final element. Thus, the compound must have meant something like ‘in a state of whirling'. For the Sumerian equivalent, we go again to Jaritz sign #410 because the Sumerian equivalent would have the predicted shape of *dî, and #410 records readings of di6 and de6, and the latter has the recorded meaning of ‘hurry', which is also recorded for du, which I will argue is the frequentative form of *di, ‘turn around'. If my analysis is correct, we should expect to find the compounded root, di, the root compounded with stative formant, *dî, unfortunately written di, the durative stem *dî, also unfortunately written di, and the frequentative *dü (di + u), also written du. We cannot distinguish in the writing system the three predicted forms written di6 except for the IE evidence of related forms.

Finally, Sumerian du, ‘hurry', can be related to IE *deu, ‘move one's forward spatially, push forward, distance one's self'; also ‘hurry', as evidenced by, for example MHG zouwen, ‘hurry, succeed'. The key difference between this form and the three others is the focus on a goal reached through repeated activity.

In Egyptian, the traces of this root are few and questionable. There are spellings like dj.w for ‘loin-cloth', a rather obvious relationship to ‘wrap around' is possible but the word is also frequently spelled d3j.w; whether this is a different word or a fuller writing of the word underlying dj.w cannot be said with any certainty since they appear to mean virtually the same thing. Egyptian d, dj, and dw are all forms of another root, PL T?A, ‘hand, give, seep', which demonstrate the thesis nicely for that verb but helps us not at all for T?E. However, in preparation for the next root we examine, we can investigate the evidence for the durative and frequentative formants in Egyptian.

b)) First, Egyptian is the masculine nominal plural formant. With regard to the employment of -w with verbs, Antonio Loprieno's excellent Ancient Egyptian: A linguistic introduction (1995) is a convenient source for information. In an inflection formerly called the ‘Old Perfective', and by Loprieno, the ‘stative', the masculine third person singular and plural is simply -w. Originally, -w was a component also of the first person singular (-k.w), masculine third person dual (-w.j), first person plural (-w.j.n), and second person plural (t.j.w.n). The ending for the second person masculine and feminine singular, the third person feminine singular, the third person feminine dual, and third person feminine plural - all have -tj. As its usage for the second person masculine singular and second person plural (t.w.j.n) as well as feminine forms in the plural make clear, the -t- of these forms is the feminine termination -t and marker for second person as well as the k of the first person singular, and is inherited from Proto-Afro-Asiatic for the West Semitic perfect, indicating that the perfect inflection had a similar effect to -w.

A sentence quoted in Loprieno will reveal the significance of the form:

gmj.n=j Hq3 j3m šm.w rf r t3-TmH

I found the ruler of Yam having gone off to the land of Tjemeh.

The implication of šm.w is that the ‘going' has been repeated or prolonged sufficiently to bring the ‘ruler of Yam to Tjemeh and does not picture him still on the road there.

Egyptian -w also is used in forms that would be considered finite, the so-called sDm.w.f inflection., which Loprieno calls the prospective. I differ with him as to its meaning only slightly.

h3j.w=k r=k m wj3 pw nj r'w

you will go aboard that bark of Re.

I would prefer to regard it as perfective, and translate:

you will have gone aboard that bark of Re.

Finally, we can look at the participial employment of -w. The -w inflections listed under the stative are already functionally participles; however, we can look at the formal category.

There is probably no clearer example of the significance of -w in participial constructions than the phrase:

DD Hr m DD.w n=f Hr

one who is giving an order is one to whom an order is being given.

We have first an active imperfective participle while the second form, DD.w, is a passive imperfective participle. More comfortably, we may translate: one who has been giving orders is one to whom orders have been given. No active participle, imperfective or perfective, is formed with -w. Obviously, the interpretation we have been offering would have supported a perfective meaning more naturally. Interpretation of -w as a passive does not offer direct support for it.

c)) In Sumerian, to indicate a persistent successful action, the formant u (‘do repeatedly') was employed. This suggests the perfective aspect. We can detect it only by a recorded alternate reading of a CVC(V) sign with u regardless what the vowel quality of the final lost original vowel may have been for transitive nouns in the singular. It appears as final u because the stress-accent has shifted to the final syllable with a vowel: thus gub/pu (gu'b/p+u), ‘built' or ‘erected' (hamTu). With marű forms, it will be directly observable because the normal-en becomes -un (presumably for -*ün). The implication is that he will ‘continue to act until completion of the verbal idea'.

d) In yet other verbs, marű modification is accomplished through the use of a suppletive verb; in some cases, different verbs are employed for singular and plural subjects. As interesting as these processes are, they fall outside the scope of our inquiry. They are vocabulary choices based on semantics not inflections.

With this background, we can return to the original object of our inquiry.

Jaritz sign #132 reads re/i, and means ‘pluck out', depicting a tool for disentangling wool fibers prior to spinning, a card; ultimately, it derives from PL

RE, which means here ‘scratch (out)'. This corresponds to Sumerian ri in ki . . . ri, ‘scratch the ground'. There is no way to tell if ri corresponds directly to RE or if it represents rî, which would reflect PIE *1. rei-, ‘scratch, tear, cut'. PL RE is also present in sign # 454, ri13 and ru2, which depicts a ‘claw' or ‘fastening nail'.

Jaritz sign #132 reads re/i, and means ‘pluck out', depicting a tool for disentangling wool fibers prior to spinning, a card; ultimately, it derives from PL

RE, which means here ‘scratch (out)'. This corresponds to Sumerian ri in ki . . . ri, ‘scratch the ground'. There is no way to tell if ri corresponds directly to RE or if it represents rî, which would reflect PIE *1. rei-, ‘scratch, tear, cut'. PL RE is also present in sign # 454, ri13 and ru2, which depicts a ‘claw' or ‘fastening nail'.

Another sign, Jaritz sign #723, which depicts a ‘millstone', reads har, which means ‘millstone' (PIE *gwer(u)-, ‘heavy'; Egyptian š3w, ‘weight') and ‘grind' (PIE *kweru-, ‘chew, grind'; Egyptian in š3b.w, ‘food') but also ‘scratch'; but also ri11. I conclude from these facts that ri11 (for *rî from *ri?), presently without meaning assigned, also means ‘abraded/scratched apart, ground up'.

Another sign, Jaritz sign #723, which depicts a ‘millstone', reads har, which means ‘millstone' (PIE *gwer(u)-, ‘heavy'; Egyptian š3w, ‘weight') and ‘grind' (PIE *kweru-, ‘chew, grind'; Egyptian in š3b.w, ‘food') but also ‘scratch'; but also ri11. I conclude from these facts that ri11 (for *rî from *ri?), presently without meaning assigned, also means ‘abraded/scratched apart, ground up'.

Another reading of the previous sign (#132) is dal, ‘dividing line'. And dal3 is a reading of sign #1, the meaning of which is unknown. In view of the semantics, it seems obvious to me that dal3 is the proper word for ‘dividing line', which is one interpretation of the ‘vertical line' of sign #1, while dal in the meaning ‘dividing line' has been drawn to #132 by its reading of re/i, which as #132 meant ‘scratch out' rather than ‘scratch in'.

In PIE, we have *reu-, ‘rip up, dig'; we also have re:- in *re:-d-, ‘scrape'; the former corresponding perhaps to Egyptian 3w, ‘death' (for ‘grave(?)', ‘scratch up, dig out'). Parallel to *reu- we should expect Sumerian *rü, written ru for *riu. We mentioned far above that sign #1 depicts a ‘scratch'; and that one of its readings is ru3. Based on the expectation of such a reading, and the predicted meaning (‘scratched = (scratched) line'), I would explain ru3, for *rü (from *riu) as meaning ‘(scratched) line', and naming literally what we see in sign #1.

Another sign, which simply depicts an ‘empty circle', Jaritz #834, reads kilib, ‘sum, totality'; this same sign reads ri3. The circle here should be interpreted as segregating off a quantity of items by circumscribing them. With this reading, we have a connection with IE re:-/r6-, ‘count' (PL RE-?A, ‘scratch' + stative = ‘state of being scratched' = ‘count(ed)'); and sign #834 also reads re/im(e/i), which may correspond to IE *re:-mo-, ‘goal = calculation'.

Another sign, which simply depicts an ‘empty circle', Jaritz #834, reads kilib, ‘sum, totality'; this same sign reads ri3. The circle here should be interpreted as segregating off a quantity of items by circumscribing them. With this reading, we have a connection with IE re:-/r6-, ‘count' (PL RE-?A, ‘scratch' + stative = ‘state of being scratched' = ‘count(ed)'); and sign #834 also reads re/im(e/i), which may correspond to IE *re:-mo-, ‘goal = calculation'.

Thus, the oldest and most appropriate reading of the vertical line which is one of the two signs underlying Jaritz sign #1 is almost certainly ru3, ‘(scratched) line'. Showing that ru3 was also used for ‘one' is the recorded meaning for it:

‘to be equal in size or rank', i.e. ‘to be as one'; in addition, sign #1 reads rum, ‘perfect, ideal', i.e. ‘number one'.

Because of this basal meaning, it is easy to see how it could have attracted the reading of dal3, ‘dividing line'; de/iš2, ‘one', and de/il(e/i), ‘one'.

Two of the commonest methods of primitive reckoning are to count by marks (scratches) and accumulate counters, like pebbles. The second sign underlying Jaritz' sign #1 is simply a ‘counting token', a small stone or pebble. The reading ana3 for this sign probably represents HHA-NA, ‘water-stone' = ‘pebble', as much as ?A-NA, ‘here-stone' = ‘this one'.

But there seems to be another word that is also associated with the concept of ‘separateness', namely še, Jaritz sign #669, which depicts the stalk of a cereal plant, and which means ‘barley' in particular and ‘grain' in general. This is PL SE, for which I would prefer a reading of *ši. But, in the meaning ‘seed', PIE *se:- in *se:-men, ‘seed', suggests that the word for ‘seed' was formed with the verbal root + the stative formant: SE-?A, ‘what has been emitted, separated'. We speculate that this caused a lengthened vowel not indicated in Sumerian, so ‘seed' would be *šî, but written ši.

But there seems to be another word that is also associated with the concept of ‘separateness', namely še, Jaritz sign #669, which depicts the stalk of a cereal plant, and which means ‘barley' in particular and ‘grain' in general. This is PL SE, for which I would prefer a reading of *ši. But, in the meaning ‘seed', PIE *se:- in *se:-men, ‘seed', suggests that the word for ‘seed' was formed with the verbal root + the stative formant: SE-?A, ‘what has been emitted, separated'. We speculate that this caused a lengthened vowel not indicated in Sumerian, so ‘seed' would be *šî, but written ši.

For the depiction of a single seed, we need to look at sign #831, which appears to me to depict a kernel of grain.

For the depiction of a single seed, we need to look at sign #831, which appears to me to depict a kernel of grain.

Another archaic precursor of this sign, in cuneiform, is written with a vertical stroke; contrasting with sign #1, which is written with a cuneiform horizontal stroke. This vertical stroke would have been oriented as a horizontal stroke in archaic Sumerian, suggesting an ‘emission' of some kind (?). This sign also reads gi3, which is what we would expect in Sumerian to represent PL K?E, ‘penis'; the meaning is not presently known. This is probably the same sign as ge15, meaning unknown, attached to sign #1.

If the combinatory rules I have devised have any validity, Sumerian e/ę can only come about as a result of the combination of a + i; and we have already seen that most Ce-signs have variants in i. In the case of sign #831, we also have the reading daš; although a meaning is not recorded for it, I feel there is a reasonable probability that we are dealing with the Sumerian equivalent of PIE *des-, ‘pluck off', and Egyptian dz, ‘flint' (‘what has been knapped off'), or PL T?A-SE, ‘hand-separate' = ‘pluck off'; and that the object we see depicted in the sign is a ‘kernel of grain', *šî. A reading for the sign is še17, and the meaning is given as ‘king'. Interestingly, Egyptian zj means ‘man' (probably better: ‘individual') and significantly, ‘man of rank'. We would emend še17 to *šîx. Rather than ‘barley', Egyptian has z.wt, ‘wheat'. In addition to other readings, sign #831 also reads ana , ‘one'.

Our investigation so far leads to the following tentative conclusions: 1) the loaf-shaped archaic sign in sign #1 is, very probably, a ‘rock'

(cf. sign #114: *nax; cf. na, ne6, and nu8, ‘stone, stele, high' [portrays stone with a vertical stroke on top], even though in the meaning ‘high', it represents ńa, or PL QHA); and, probably, in addition HHA-NA, ‘water-stone' = ‘pebble'; i.e. ana3, although the only meaning recorded for it is ‘one' (?A-NA, ‘here-one' = ‘this one').

(cf. sign #114: *nax; cf. na, ne6, and nu8, ‘stone, stele, high' [portrays stone with a vertical stroke on top], even though in the meaning ‘high', it represents ńa, or PL QHA); and, probably, in addition HHA-NA, ‘water-stone' = ‘pebble'; i.e. ana3, although the only meaning recorded for it is ‘one' (?A-NA, ‘here-one' = ‘this one').

Two readings for sign #1 that have not been assigned a meaning, in3 and ina, are strongly suspected by me to be imprecise transcriptions for *ęnx and *ęnax, representing ?A-?E-N(A), ‘here-like-one' = ‘(this) one'). The line of thought is supported by the fact that the third person singular ergative pronoun was, in Old Sumerian, a.ne (an[a] + -e, ergative), which later became e.ne.

The plain reading na, meaning ‘stone', properly belongs to sign #114 and sign #453 (na4), which narrows the meaning to ‘(shiny) stone', or ‘jewel'. Also, ‘one' as a human counter, is found in sign #611 as na6, interestingly, we find a female equivalent in ni4 (for *nęx), which is ‘human female' (for NA-?E, ‘one-like'), in sign #921. The same formulation was also used for ni, ‘he, she, it, that one', written with sign #456.

It appears, however, that, in view of the meanings of ‘man, human, strength', that these readings were also drawn to sign #1 so that, at some point, sign #1 had the improper readings of nax and nęx. The latter could be understood as ‘one-like', i.e. ‘one', and would be equivalent to ni (for nęx) that we find in sign #456, where it is recorded to mean ‘he, she, it, one'; and ni3 (for nęx), that we find in #970 meaning ‘thing'. But nęx could also be understood as ‘stone-like' = ‘hard', and I believe this is the source for ne3, ‘strength' (better ‘hardness'), found in sign #789; and is also the reason sign #1 acquired the meaning of ‘strength/hardness'. ‘Strength' in the sense of muscle-power is properly represented by â2, which is PL HA, ‘air, wind, lung-power'.

It appears, however, that nęx brought along a reading of sign #1 as a, ‘physical strength'; this shows up as a meaning for #1 of ‘moaning, cry of distress', Sumerian a (better â). This exclamation is also known in PIE as *a:, and in Egyptian as j. None of these languages give us any precise idea of what consonant preceded a to cause it to be long so we look to Arabic where we have the ?alif of lamentation. As a cry of woe, we should reconstruct PL ?A, ‘here!', as an exclamation designed primarily to focus attention on the speaker. This development, in turn, precipitated the readings makkaš, ‘wailing; clamor'; tal(4,5), ‘noise', and til(5,6), ‘noise', which, otherwise, have no legitimate connection with the sign but were connected through meaning with â, ‘cry of lamentation'; and phonetically with dal3 and de/ile/i.

At some point in time later than the original assignment of meanings and values to this sign, a new compound was originated, a + šix (written še; borrowed from #831), ‘here-separate' = ‘this one', which was changed to aša, ‘one', probably on the basis of final -a in ana; this reading, in turn, attracted ašša, ‘clamor'. Finally, it developed into aš. This abbreviation suggests that at the time the compound was formed, stress-accent had shifted onto the first syllable, suppressing the final vowel. This drew aš, ‘spider', as a reading from its proper sign aš5, #906, a combination of #901 (‘[woven-]web') + #725 (‘[fish-]trap'). In addition, as/z3, meaning unknown, was drawn to #1 purely for its phonetic similarity to aš.

Interestingly, ana3, a value properly belonging to #1, was transferred to #831 as *ana, ‘one'; and iš4 (probably *ęšx), meaning unknown, but probably a variant of aš as e.ne is of a.ne, also came back to be attached to #831. And this seems to be the case with

de/iš, ‘one' , as well.

Totally unjustifiably, tal4, ‘noise', til5, ‘noise', and makkaš, ‘wailing, clamor', have been attached to sign #831; apparently, the fact that both signs, #1 and #831, meant ‘one', was sufficient for attaching readings and meanings from #1 to #831

A very interesting case of transference of a reading to sign #1 is sagtag, which we would prefer to rewrite as *sa(n)g[~]3tag (‘head+hold'), ‘pillow (?); wedge; triangle'. The connection to #1 is through its adopted reading na. Sign #774, which depicts a ‘head on a pillow with legs indicated below', reads na2, and means ‘lie down' but also ‘protect' and ‘darkened'. In the meaning ‘protect', it corresponds to IE *na:-, ‘help, protect' (cf Old Indian ná:-tha-, ‘protector'). In our opinion, this also corresponds to Egyptian nj, ‘turn away, avoid'. These three are reflexes of PL NA-HA, ‘put (to be) inside'. The IE application seems reflect this basic idea: ‘put inside (under the care of; provide a place of refuge/sanctuary for'). The Egyptian application seems to similar but with a slightly different emphasis: ‘put inside (to eliminate contact with/influence from'), ‘put one's self inside (darken', of sun), ‘shrink from'. This latter corresponds to a meaning of ‘darkened' for na2. We can see that though at first glance they are different, IE *na:-, ‘protect', and *na:-, ‘fear, be ashamed', are related; the latter is simply reflexive.

An additional IE root of interest is *na:u-, which, among other meanings, has ‘sink down exhausted', which correlates most directly with Sumerian nu2, ‘lie down (to sleep'). This seems to reflect PL NA-HA-FHA, ‘put one's self inside repeatedly/completely', or ‘pass out'. The expected Sumerian reflex would be nâ + ű = nŰ, written nu(2).

Finally, we must discuss two further readings of sign #1:

de/il(e/i), ‘one; single; only; alone; unique'

de/iš2, ‘one'

Although sign #807 reads *de/iš, ‘one', we believe these roots are closely enough related that they properly should be referred to the same sign.

Although sign #807 reads *de/iš, ‘one', we believe these roots are closely enough related that they properly should be referred to the same sign.

For us, the decisive factor is that didli, ‘several, various' (a reduplication of de/il(e/i)), is a reading of sign #2, which is a reduplication of sign #1.

The probable base for both of these is Sumerian de/i, two readings of sign #807, which depicts an ‘object divided by two lines into thirds', one of the meanings recorded for di is ‘(legal) judgment', which we understand as ‘portion, allotment'. The reading ti5 for sign #1 is quite possibly properly read dix, **'part'.

We would be disappointed not to find such a venerable word in Egyptian but we do find it as dj, ‘provision(s)', i.e. ‘portion'. The sign with which it is written clearly depicts a ‘triangular section of bread with additional portion marked'. This word is also used as a near synonym for d(w), ‘give', in the sense of ‘allot'.

We would be disappointed not to find such a venerable word in Egyptian but we do find it as dj, ‘provision(s)', i.e. ‘portion'. The sign with which it is written clearly depicts a ‘triangular section of bread with additional portion marked'. This word is also used as a near synonym for d(w), ‘give', in the sense of ‘allot'.

The PL prototype for these is T?A-?A-?E, ‘strip'-stative-durative = ‘stripping (for distribution)'. Therefore, the Sumerian is better read as dę(x), written de. The better reading for Egyptian dj is probably *djj. We find this easily in PIE as *da:i-, ‘part, cut apart, tear apart'.

Under *da:i-, we also find *d6i-ló-, ‘part', which easily corresponds to Sumerian de/il(e/i), which we can now correct to *dele for **dęlę (T?A-[?A-]?E-NHA-?E, with the added elements meaning ‘go-back-and-forth' = ‘saw'-durative, yielding ‘what is stripped by sawing', or ‘cut off portion/part').

This leaves only de/iš2, ‘one', for which we should account. The first element is T?A-[?A-]?E-, ‘part', while the second element is SE, ‘separate'.

********************************************************************************

the latest revision of this document can be found at

HTTP://www.oocities.org/proto-language/SumerianValuesMeanings.htm

Patrick C. Ryan * 9115 West 34th Street - Little Rock, AR

72204-4441 * (501)227-9947

PROTO-LANGUAGE@msn.com

NOTES

1.

Although no recorded meaning of ‘foot' is found for #410, sign #141 means ‘(possibly, left) foot', depicts, very similarly to #410, a ‘lower (left) leg and foot', with the modification that attention is called to the kneecap area by a ‘cross in a box'; it reads gub3 and gubu2, and, we will see, importantly, kub/p3, and kab/p. The meaning ‘foot' has been identified for hub2, another reading of this sign; and for the phonologically unrelated reading du.

2.

We would emend the reading of de3 to Te3, and analyze it as a product of *tu (PL THO, ‘approach' (cf. Sumerian šu...tu-tu, ‘approach'), effectively, a marker of future completion + e, ‘locative-terminative postposition' = ‘for'; this is, effectively, a ‘dative of interest', and can be compared to PIE -*(e)i, dative singular, both probably representing PL HE-?E, ‘moving across from, leaving/going (to/for)', i.e. ę (Sumerian ę [written e], ‘go (out)'; interestingly, the sign [Jaritz #574] for it depicts a ‘river-channel'; the basal meaning I have assigned to HE is ‘river').

It is clear from PIE that the future formant has t rather than d; and the Egyptian equivalent, t, narrows the vowel to o. This mandates PL THO, which becomes Sumerian tu.

The letter T, as employed by me here, represents Jaritz' t. (dotted t), supposedly the Semitic emphatic dotted t.. I believe that T arose as a retroflex articulation from the labial character of apicals followed by o/u like tu, which, perhaps, additionally had a glide (/twu/). When Sumerian tu was combined with ę, tu gave up its vowel but preserved its phonological and semasiological integrity by becoming retroflex or emphatic: tu + ę = Tę.

This future-forming element occurs in to other major constructions in Sumerian: as -da (tu + ?a/â [PL ?A, {‘top' =} ‘on'], Sumerian locative); and -dam from -*tu-?a/â-mę, combined with the enclitic copula (PL MHA-?E, ‘being active at'). The sign for da, Jaritz #629, also reads Ta2; the sign for dam, Jaritz #922, also reads Tam. Based on this analysis, in these three constructions only: de3 should be emended to Tę3; da should be emended to Tâ2; and dam should be emended to Tâm.

Based on this analysis, I translate: ‘. . . so that its houses shall become utterly destroyed'.

3.

The word for ‘dry' poses a number of interesting problems. First, we have Jaritz sign #937, which depicts a ‘zig-zag arrangement of single mud bricks', and according to Jaritz reads siga, ‘mud brick' and ‘excrement'; siga is almost certainly to be analyzed as sig, ‘*dry' + a, stative = ‘*dry'; it also reads according to the Sumerian Dictionary sig4 and šeg12.

To ‘dry' seems a simple concept until one is forced to scrutinize it. First, one may ‘dry' something by wiping it was an absorbent material of some kind; second, something may dry itself by releasing its moisture; and it may do so because it is heated, because the air is cold and dry around it, or because it simply leaks.

It is, with great difficulty, that we can hopefully separate the words employed for these subtle nuances of ‘dry' when, it appears, that the ancient languages which we are studying may, themselves, have had a similar problem. We have the further problem that not all the data which may have existed has come down to us; and what has, may have been misinterpreted. What follows, then, is informed speculation but speculation nonetheless.

Since we know that Sumerian bricks were sun-dried mud bricks, it seems most likely to associate the readings above with the idea of ‘seepage' and ‘dry' (as its ‘bricks'). The PL monosyllable most frequently associate with this general idea is SE, which would show up in PIE as *se/o, in Sumerian as ši, and in Egyptian as z. Apparently, this sign was used also for ‘excrement', through the commonality of the idea of ‘seepage/emission', the natural province of SE. On the basis of the consonant correspondences cited above (which have been developed through a large number of less problematical equivalencies), we can connect Egyptian zT, ‘pour out' (probably better: ‘*trickle out'). If this is truly a cognate, it calls for an origin in PL KHO or K?O as a final element: SE-KHO or SE-K?O. Egyptian zT.j, ‘strew, scatter', corresponds to PIE *seg-, ‘sow', and Sumerian sag2, ‘scatter'; since Egyptian z can also represent Sumerian sa, and PIE g represents PL K?, and Egyptian T represents K?O, that the PL word underlying these three words derives from the form: SA-K?O, ‘strong(ly)-twist', a fair description of the motion of the hand in scattering something back and forth.

Now SE-KHO (‘excretion-cover', i.e. ‘cover with excretion', or ‘seep out'); this would also appear as Egyptian zT, and could semantically be interpreted as ‘*trickle out', corresponding to our modified ‘pour out'; SE-KHO would appear in PIE as *sek-; and under *1. sek-, we find ‘run off (liquid)'; apparently, a semantic match. Jaritz sign #339 includes the readings še6 and šeg6 for ‘dry a field, fire pottery'; but these activities involve a slightly different method of ‘drying'.

One of the characteristics of the Sumerian writing system is that a very large number of signs with medial e are usually found as an entry in the form e/i. Whether this variation is due to our inability to interpret the evidence, or the signs actually had these dual values, or the Mesopotamian, non-Sumerian scribes, from whom most of our evidence comes, were confused or not able to properly make the necessary distinctions, it hardly matters to us at this late date. While I wish that it did not, it allows us the option of emending any medial recorded e to i based in its manifestation in PIE as simple *e; and conversely, the option of emending any medial recorded i to e based in its manifestation in PIE as simple *ey.

To complicate matters further, a very large number of signs with final stops (b p d t g k) are usually found as an entry in the form b/p, d/t, g/k, so that the reading recorded for one of these signs cannot really specify which of the pair of stops is found in the uninflected form. It has been theorized that words ending in a voiceless stop were voiced (or, at least, deaspirated if that was rather the basis of the contrast) between vowels so that both values are positionally valid allophones. While this make no difference for Egyptian comparisons since the contrast between all pairs of stops and affricates and some most others is not based on voice or aspiration (d represented originally /ta/ and /te/ while t represented /to/), it prevents fully satisfying PIE cognates where, so far as our reconstruction safely allows, a voice distinction was inherited from PL glottalized stops and affricates (P?O/P?FO and PHO/PHFO).

Therefore, we will first propose that the reading of Jaritz sign #339, še6, for ‘dry a field, fire pottery' corresponds to PIE *sei-, ‘drip, run'. I will emend the reading of the sign to *ši6 based on an emended entry of *še/i6 justified, I hope, by the facts presented above. Furthermore, since I believe that while the product of early Sumerian /ai/ was ę, written e, the product of /ii/ (earlier, /ey/) was î, written i. Accordingly, I further emend the entry to *še/i/î6. This represents SE-?E-KHO (‘excretion-like-cover', i.e. ‘cover as if with excretion' (‘cover with what has been emitted'), or 'pour out'. While Egyptian zT shows no trace of the introduced formant (if ever there, it may have been lost; or, though I am not prepared to accept this, it was there but defectively not written), I believe we can identify it in PIE *seikw-, ‘pour out, sift, run, trickle'. I propose that this word is derived from *sei- with the root extension *-k but that it has exceptionally drawn a *w to the final stop arising from a former glide occasioned by a pre-PIE form in *o, or possibly a further root extension with w. PIE apparently preferred to limit root extensions to CVC or CVi/uC, and this might, by itself, have been enough to motivate a modification of CVikw- to CVikw in view of the existence of a phoneme /kw/. I freely admit that if the /kw/ was original in this word, it would correspond to PL XH, Egyptian š or h, and Sumerian š or h. The comparison would then not hold. Patient readers will remember that I mentioned šeg6 for ‘dry a field, fire pottery' above. Based on the discussion above, I emend it to *šîk6 directly corresponding to PIE *seik(w)-.

Another major problem with which we have to contend is that, when the original vowel qualities in pre-PIE were lost (*e, *a, *o became Ablauting *e/*o), roots, formerly distinguishable by the vowel, became impossible to properly separate, particularly if the meanings were purely coincidentally similar. IEists, without any evidence within PIE to make a once valid distinction among these, were forced to create overly broad definitions in order to group together originally disparate roots.

A particularly illustrative example is found in Pokorny's *1. seu-, ‘juice, something damp'; verbal: ‘press out juice' and ‘rain; run', and in further constructions ‘drink noisily (juice), suck'. Though he hesitated to add it in the definition quoted in full above, he included an item: *seu-d-, ‘dirty (verb)'. And ‘sucking' (‘admitting') and ‘emitting liquid' are really rather antipodal.

The fault is not Pokorny's, dealing as he had to, with the identical forms of roots reconstructed. The root will show, I hope, the essential value and necessity of reaching out beyond PIE to other languages, like Egyptian, which, in most cases of cognates, can tell us whether the PIE reconstructed root-vowel *e/o represents a pre-PIE *o; and Sumerian, which can confirm o with u and *a and *e with a and u.

First, let us look at Sumerian su3, ‘sprinkle', a reading of Jaritz sign #677, which is a form of #675, depicting a ‘snake'. Sign #677 has a number of short straight lines in the snake's head, called gunu. These commonly applied lines seek to focus our attention on some specific aspect of a larger concept.

First, let us look at Sumerian su3, ‘sprinkle', a reading of Jaritz sign #677, which is a form of #675, depicting a ‘snake'. Sign #677 has a number of short straight lines in the snake's head, called gunu. These commonly applied lines seek to focus our attention on some specific aspect of a larger concept.

In this particular case, I believe the creator of the sign wished us to understand a spitting snake, usually not lethal but quite painful. I would expand su3, ‘sprinkle', to ‘*spray, *spit'; and I believe this modification allows us to understand why this reading was attached to this sign.

Another feature of the Sumerian transcriptions that have survived for us is that a large number of words with initial s also have additional readings with š: e.g. su and šu11 are both readings of Jaritz sign #8. Because of the basic meanings associated with SE (PIE as *se/o, Sumerian as ši, Egyptian z), with a meaning like ‘sprinkle, *spray, spit', I believe a connection with it is more than likely. Accordingly, I emend su3, ‘sprinkle', to ‘*spray, *spit', to *šux, ‘sprinkle', to ‘*spray, *spit'. Of course, uncompounded, we would expect *ši but neither this reading nor *šu is recorded for #677, and to indicate this, I subscript x to indicate its lack of attestation. Sumerian šux, presuming we have rightly reconstructed it, is likely to be a result of šix + u, frequentative (PL FA), which shows up in PIE as *-w. The stem 'SE-FA would mean ‘excreting/emitting repeatedly'; and this meaning corresponds nicely to Pokorny's*seu-, ‘rain', and, perhaps ‘run (liquid)'. The combination of ši and u would, in my opinion, most likely lead to a realization of /ü/, which, unfortunately, was written u, at least in the transcription that has come down to us. The common word in Egyptian for ‘drink' is zwr but in very old Egyptian, one finds zw in this meaning. It is possible to think of this as a noun on which the verb was built, with a meaning like ‘rain-water' that was generalized to any ‘drink' but I realize this takes, perhaps, too great liberties semasiologically. Still, worth a mention, I think.

The second meaning hiding in PIE *1. seu- is ‘suck(le)', which I would propose goes back to PL SO-FA-K?A, ‘pull-repeatedly-chew', really properly ‘suckle' rather that ‘suck'. This would correspond nicely to PIE *seug-, ‘suck'. For this, we would anticipate Sumerian *sUg (/so:g/) written *sug, but it cannot be found. This would result in Egyptian *swk but it does not appear for us either.

At this point, some readers may be thinking that my analysis has, perhaps, gone awry here. Unfortunately, the evidence available is such that one cannot help but be forced to be somewhat circuitous.

We saw above that PIE *sek- and *seik(w)- bore an interesting relationship to each other. I hope I have been able to make a plausible presentation to show that seik(w)- is likely to be an elaborated form of *sek- with only a small practical difference of meaning. I now hope to make a plausible argument for the existence of a simpler form of SO-FA-K?A, with an extension of the meaning of ‘suck' to ‘absorb'. SO-K?A, ‘absorb', makes a little sense in that ‘absorption' is basically the same process as ‘sucking' but is not easily reducible to individual repeated exertions; this lends some support for the interpretation of FA that we have advanced in other analyses.

First, let us candidly admit that we have no solid evidence of a PIE *sek-, ‘*dry*, except the reduplicated *si-sk-us, ‘dry', listed under *1.sek-, ‘run off'. However, it does not seem unreasonable to interpret Egyptian sk as ultimately meaning ‘suck/absorb'. With Sumerian, we have tantalizing hints of a theoretical *sug, which we expect as a Sumerian response to SO-K?A. Jaritz sign #820 reads, among other readings, suku and šug/k/q. In view of the second reading, we feel justified in proposing *sug. For the meaning, the best interpretation I can give is ‘piece of bread with crust marked by one or two horizontal lines'.

First, let us candidly admit that we have no solid evidence of a PIE *sek-, ‘*dry*, except the reduplicated *si-sk-us, ‘dry', listed under *1.sek-, ‘run off'. However, it does not seem unreasonable to interpret Egyptian sk as ultimately meaning ‘suck/absorb'. With Sumerian, we have tantalizing hints of a theoretical *sug, which we expect as a Sumerian response to SO-K?A. Jaritz sign #820 reads, among other readings, suku and šug/k/q. In view of the second reading, we feel justified in proposing *sug. For the meaning, the best interpretation I can give is ‘piece of bread with crust marked by one or two horizontal lines'.

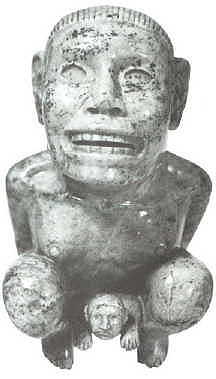

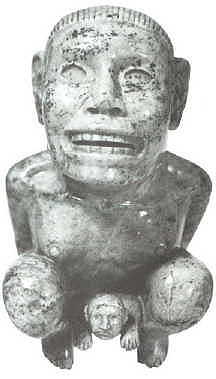

If I am correct, and the sign is illustrated here so readers may form their own opinions, the ultimate meaning is ‘sop', i.e. ‘wipe(r)', and by extension, ‘drie(r)'; as an, I hope, interesting aside, the English word ‘sop' is derived *seub-, listed under the elaborated stem we have been discussing (*1. seu-).

Semi-finally, before we return to the main thesis, we may notice what we will explain as reflexes of PL SO-P?A, ‘pull-part'" = ‘lip' or ‘pull-done a little' = ‘kiss', which is a small closed inhalation after all. Jaritz sign #36 also reads bu3, which I believe corresponds to PIE *bu, ‘lip, kiss', which may be onomatopeic though an analysis as P?A-FA, either ‘piece-pair' (‘lips') or ‘split-repeated' seem plausible interpretations; there seems to be no known Egyptian equivalent.

Semi-finally, before we return to the main thesis, we may notice what we will explain as reflexes of PL SO-P?A, ‘pull-part'" = ‘lip' or ‘pull-done a little' = ‘kiss', which is a small closed inhalation after all. Jaritz sign #36 also reads bu3, which I believe corresponds to PIE *bu, ‘lip, kiss', which may be onomatopeic though an analysis as P?A-FA, either ‘piece-pair' (‘lips') or ‘split-repeated' seem plausible interpretations; there seems to be no known Egyptian equivalent.

We may first notice the Sumerian phrase: ne . . .sub or su.ub, which somewhat implies a long vowel (*sűb) when sub was available as a single sign. Sumerian *nę may be a reflex of NA-?E, ‘nostril-like' = ‘nose'? But we have no clear cognates in PIE or Egyptian to give us further guidance. Outside of that phrase, sub, a reading of sign #36, is known to mean ‘kiss' and ‘venerate'. The sign is a combination of ‘mouth' (#15) and ‘(left) hand' (#651), which suggests ‘venerate' as the primary meaning of this compound sign, perhaps in distinction to the phrase mentioned above which indicates a more intmate ‘kiss'. PIE *seub- suggests we may be dealing with this elaborated form derived from the now familiar *1.seu-, in which case we could emend sub to *sűb. In view of the composition of the sign (‘mouth' + ‘hand'), it is even possible that we have a compound: *šu-bu3, ‘hand-kiss', reduced to šub under the influence of the stress-accent, and that the proper meaning is more narrowly ‘venerate', i.e. ‘kiss the hand', since the sign also reads šub2. Finally, it is possibly that the simplest option of all is the right one: sub represents SO-P?A.

We simply do not have enough information to make a strongly defensible argument. It is also possible that those who devised the system reckoned with the idea that each sign might have multiple readings and meanings. And finally, since PIE *b had a tendency to develop into PIE *w generally, it might be that some derivatives under listed under *1.seu- are derived not from SO-FA but rather from SO-P?A.

What suggests the simplest compound may be, at least for Sumerian and Egyptian, preferable to the more elaborate PIE forms is Egyptian sp.t, thought to be, more fully, sp.tj, i.e sp, ‘*lip' (stem) + -tj, feminine dual ending. Egyptian s, when it is not an indifferent writing for z, which lost its distinctive character fairly early, represented ab origine, /so/; and thus corresponds to the vowel we have reconstructed for the Proto-Language and the reflex of which we actually found in Sumerian.

Now we may return to PL SO-K?A, for which, we have explained above, we expect Sumerian *sug. In addition, we propose that the path leads from ‘absorb' through ‘dry' to ‘wipe' as above. But, let us linger at ‘dry'. Egyptian sk,‘wipe out/away', is attested; it could just as easily refer to freeing from dust or dirt as it could to absorbing water that results in dryness. We can now remember PIE *si-sk-us, ‘dry'. Reduplication strongly suggests an unreduplicated form in a related meaning. If we can assume PIE *sek-, ‘*dry', it would correspond to Egyptian sk, ‘wipe away', and, by extension ‘dry off'. But, sek should correspond to Sumerian *suk not *sug.

Now we may return to PL SO-K?A, for which, we have explained above, we expect Sumerian *sug. In addition, we propose that the path leads from ‘absorb' through ‘dry' to ‘wipe' as above. But, let us linger at ‘dry'. Egyptian sk,‘wipe out/away', is attested; it could just as easily refer to freeing from dust or dirt as it could to absorbing water that results in dryness. We can now remember PIE *si-sk-us, ‘dry'. Reduplication strongly suggests an unreduplicated form in a related meaning. If we can assume PIE *sek-, ‘*dry', it would correspond to Egyptian sk, ‘wipe away', and, by extension ‘dry off'. But, sek should correspond to Sumerian *suk not *sug.

If we wish to find a PL origin for PIE *sek-, instead of SO-K?A, we need SE- PL SO-KHA, ‘emit-desire', i.e. ‘(tendency/desire to) emit/expel (liquid)', i.e. ‘waterproof'. And, it would produce Sumerian *šik.