| Previous section | Table of contents | Next section |

|---|

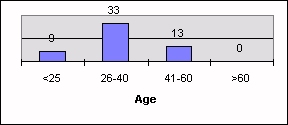

I had conducted one study on the Internet in January 1998. A total of N=30 court interpreters, mainly from the USA and UK, ranked five defined strategies according to their likeliness to be used in typical interpreting situations. The strategies were 1. omission of term, 2. approximate equivalence, 3. explanation of concept, 4. loan translation, and 5. direct loan. The respondents marked each of these strategies according to usage by picking one of the following alternatives: a) never/almost never, b) seldom, c) occasionally, d) often, or e) almost always/always. (See Niska (1988) for a more detailed discussion.)

I then went on to use the same study to explore the attitudes of Swedish community interpreters to the same strategies. Those results were presented together with the court interpreter survey in our previous paper (Niska 1998). For the Swedish interpreters I had, however, added a separate survey of a large number of background variables that we felt could influence the subjects' choices of strategy. The present paper will focus on the results of that background study.

1) To explore the attitude of community interpreters in Sweden towards terminology that has been introduced or recommended by language planning authorities (organisations or individuals), including the perceived responsibility of interpreters in language planning (part I of the study);

2) To explore which strategies interpreters use when dealing with terms and concepts that do not have an exact equivalence in one of the working languages (part II).

The study was conducted as a survey in the form of a two-part questionnaire. Part II, the strategy survey, has been discussed earlier (Niska 1998), and will be referred to only briefly in this paper.

The survey has to a large extent been inspired by Laurel Benhamida's doctoral dissertation Translators and Interpreters as Adopters and Agents of Diffusion of Planned Lexical Innovations: The Francophone Case (Benhamida 1989), cf. section 4.4.

Sociolinguistic variables were (a) mother tongue, (b) other languages than mother tongue (questions 6-7);

Socioprofessional variables were (a) training (general education and professional training), (b) authorisation, (c) languages used in work, (d) main working areas and interpreting technique, (e) kind of employment, (f) professional experience, (g) adoption of material innovations for use in work (questions 8-18).

Experience of terminology work (a) knowledge of sources for new terminology, (b) own terminology work, (c) knowledge of terminology planning organisations (questions 19-21).

Part II was a survey of interpreters' attitudes towards five given strategies for the treatment of terminological neology in interpreting situations. The strategies were 1. omission of term, 2. using near equivalent, 3. explanation of concept, 4. loan translation, and 5. direct loan. Interpreters had to state how often they used each strategy in a typical interpreting situation: a) almost never/never, b) seldom, c) occasionally, d) often, or e) almost always/always. The results of part II are reported in Niska (1998) and will be mentioned here only in the section Arabic interpreters' preference of interpreting strategies.

(2) Gender (n=57). 65 % (n=37) of the respondents were female, and 35 % (n=20) male. This is practically the same distribution as in Benhamida's (1989:96) study (64.2 % female).

(3) Place of birth (n=53). Afghanistan 2, Albania 1, Algeria 1, Bosnia 4, Croatia 1, Egypt 1, Finland 1, Iraq 7, Iran 6, Kosovo 3, Lebanon 2, Poland 3 Russia 1, Somaila 4 Sweden 7, Syria 1, Turkey 3, Yugoslavia 6.

(4) Current domicile (n=49). The respondents came from 29 different places, mainly in largish towns in Southern Sweden (Stockholm and southwards); the data have not been analysed in detail.

(5) Number of years in Sweden (n=49). The mean duration of stay was 12 years, the median was 8 years, and the mode 5 years. The number of years spent in Sweden ranged from 4 to 37.

| Mother tongue (n=53) | Other languages except Swedish (n=48) | Working languages

besides Swedish (n=38) |

| - | English, German, Russian | Serbian |

| Albanian | English | |

| Albanian | French, Serbian | |

| Albanian | Macedonian, Serbian, Serbo-Croatian | Albanian, Serbo-Croatian |

| Albanian | Serbian, English | Albanian, Serbian |

| Albanian | Serbo-Croatian, English | Albanian, Serbo-Croatian |

| Arabic | ||

| Arabic | English | Arabic |

| Arabic | English, French | Arabic, English |

| Arabic | French | Arabic |

| Assyrian | Arabic | Arabic, Assyrian |

| Assyrian | Arabic | Assyrian, Arabic |

| Assyrian | Arabic, Kurdish | |

| Azeri-Turkish | Persian, Dari | Persian, Dari, Azeri-Turkish, Turkmen |

| Bosnian | English | Bosnian, Serbian |

| Bosnian | Russian | |

| Dari | ||

| Dari | Pashto, Polish | Dari, Pashto |

| Farsi | Persian, English, some Swedish Sign Language | Persian, eventually Sign Language |

| Finnish | German, English | Finnish |

| French, Arabic | French | Arabic, French |

| Croatian | English, German | SKB |

| Croatian | Serbian, Bosnian | Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian |

| Croatian | Croatian | |

| Croatian (Serbo-Croatian) | Serbo-Croatian | |

| Kurdish | Arabic | Kurdish, Arabic |

| Kurdish | Persian, English | Sorani |

| Kurdish | Serbian, Arabic | Serbian, Kurdish, Arabic |

| Kurdish | Turkish, English | Kurdish, Turkish |

| Kurdish | German, Spanish, English, Arabic, Persian | Sorani, German, Spanish, English |

| Kurmanji | Turkish, English, German | Kurmanji, Turkish |

| Persian | English | |

| Persian | English | Persian |

| Polish | ||

| Polish | French, German, English, Latin, Russian | French, Polish |

| Polish | Serbo-Croatian, Russian | Serbo-Croatian, Polish, Russian |

| Russian | English | |

| Russian | English | |

| Serbian | English | Serbian |

| Serbo-Croatian | English | |

| Serbo-Croatian | English, some French | Serbo-Croatian |

| Serbo-Croatian | French, English | |

| Serbo-Croatian | Hungarian, German, English, Bulgarian, French | Serbo-Croatian, Hungarian |

| SKB | English | |

| SKB | Russian, English | |

| Somali | ||

| Somali | Arabic, English | Somali, Arabic |

| Somali | English | |

| Somali | ||

| Sorani | Arabic | Sorani |

| Sorani | Persian, Azerbaijani | |

| Swedish | English, German, French | |

| Swedish | Serbo-Croatian | Serbo-Croatian |

| Swedish | Spanish, English, Portuguese | Spanish |

| Syrian | Kurmanji, Turkish | Syrian, Turkish, Kurmanji |

SKB = Serbiska/Kroatiska/Bosniska (Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian)

Table 5-2 Linguistic profile of respondents.

It seems safe to assume that respondents who have not reported a working language interpret primarily to and from their mother tongue.

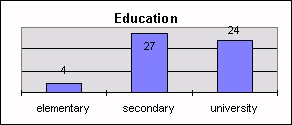

(9) Interpreter training (n=55). The answers to this question have been grouped into four categories: 1. only introductory course (normally 30 h), 7 % (n=4); 2. introductory course plus one area-specific (e.g., social, health care, legal interpreting) course (à 80-90 h), 36 % (n=20); 3. introductory plus two or more area-specific courses, 49 % (n=27); 4. full-time interpreter training course (at least one semester), 7 % (n=4).

In other words, over half of the respondents have received fairly extensive interpreter training, consisting of several short courses or a longer comprehensive course.

(10) Authorisation (n=10). 10 persons reported they were authorised interpreters, 4 of them with special competence as court interpreters, and 1 with special competence as medical interpreter.

(11) Working languages, see table 5-2.

(12) Employment conditions (n=56). All respondents report that they are free-lancers.

(13) Economic dependency of interpreter work (n=55). While the majority, 52 % (n=29) report not being economically dependent of interpreting jobs, almost as many (48 %, n=27) report that they are.

(14) Working areas (n=53). Most respondents (35) work as community interpreters, 21 (also) as court interpreters, only one as a conference interpreter, and 8 state "other" (e.g., translation).

(15) Interpreting technique (n=48). 73 % (n=35) work mainly in consecutive, 4 % (n=2) mainly simultaneous, and 23 % (n=11) report "both".

(16) A, B, C languages for conference interpreters. The only conference interpreter in the sample gave Albanian as A-language and did not state B or C languages.

(17) Job experience (number of years) (n=58). The answers to this question have been grouped into three groups: under 1 year, 1-5 years, and over 5 years. A large proportion of respondents, 26 % (n=15) have very little, under one year, professional experience as interpreters. 45 % (n=26) have been interpreters for 1-5 years, and 30 % (n=17) have more than five years' experience.

(18) Use of computer aids (n=47). The purpose of this question was to give a picture of interpreters' general adoption of material innovations, and more specifically the use of computers for use in terminology work. 11 interpreters reported that they had WWW access, 10 that they use CD-ROMs, and 12 respondents compile their own glossaries on the computer. But no less than 34 respondents report that they did not use any of these aids.

Dictionaries (general and specialised) 35

Training courses, teachers and course material 9

Newspapers 7

Books 7

Internet, WWW

6 Colleagues 3

Foreign channels 2

SIV (National Board of Immigration) 2

Special journals 1

Acquaintances 1

Contact with home country 1

Foreign news broadcasts 1

Arbetsförmedlingen 1

Försäkringskassan 1

(20) Own terminology work (n=58). Most of the respondents report that they are engaged in systematic work with new terminology. 40 % (n=23) do terminology work by themselves, and as many as 45 % (n=26) in co-operation with others. Only 16 % (n=9) report not doing terminology work.

(21) Knowledge of term planning organisations (n=27). Only 27 interpreters responded to this question, 17 just to tell that they did not know of any such organisations. The following organisations were mentioned by the remaining 10 persons:

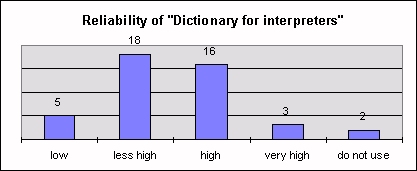

(23) Reliability of Ordlista för tolkar (n=43): This "Dictionary for Interpreters" including about 6 500 terms from the social, health care, legal, and labour market areas is at present available in 17 immigrant languages. It is thus not available in most of the immigrant languages in Sweden. 43 interpreters answered this question, and, contrary to the preceding question, most respondents, 53 % (n=23) consider the reliability of this glossary to be less high or low. 44 % (n=19) rate the reliability as high or very high. Only 2 respondents, 5 %, do not use the glossary — the same caveat as in the preceding question regarding this option is valid here; the question is unfortunately equivocal in this regard.

(24) Usage of recommended terms (n=58). Regardless of the insufficient resources and the doubtful quality of the terminological recommendations available, most respondents 72 % (n=42) report that they stick to the recommended terminology "as much as they can", and 6 % (n=10) do it "occasionally". Only 10 % (n=6) do not keep to those recommendations "consciously"; the material does not show the reason for this.

This question was deliberately formulated in an imprecise way (we did not define what we meant by keeping a language clean), partly because it was difficult to make it more specific, but mainly because the word "clean" was supposed to trigger possible "puristic" feelings in respondents.

For a discussion about purity in this context, see section 2.5 Linguistic purism.

(26) The interpreters' language planning responsibility (n=57). This question asks whether interpreters should be engaged in "language care" (språkvård), a Swedish term that equals to "language planning" as we have defined it in this paper. The options are yes, no, no opinion. The majority of respondents, 63 % (n=36) believe that the interpreter should work with language planning, and only 11 % (n=6) are against it. There is however a great percentage, 26 % (n=15) who state that they do not have an opinion. This may indicate that the question is controversial.

(28) What do you do if the client does not understand a special term? (n=54) The different answers have been lumped together in groups under more general headings.

The following table clearly implies that explaining the concept is very usual in community interpreting situations. This can be done either by the interpreter alone (n=26), or by the interpreter asking the other party (usually the service provider/authority) to explain and then interpret the explanation (n=18). Rephrasing in easier language is reported by 4 respondents. Waiting for the parties to solve the problem (n=3) and doing nothing (n=2) may be the same thing, but the comments of the last two examples are rather revealing of respondents' non-committed attitudes towards the clients. One respondent gives the alternative of translating literally, and one respondent apparently is able to make lightning fast judgements about clients' educational and physical status in the course of interpreting: explain or wait "if the client is highly educated and otherwise alert".

Table 5-4 Interpreters' action if the client does not understand a special term

(29) Only for Finnish interpreters: How often do you turn to the Swedish-Finnish Language Council for terminology help? No answers were received.

| Previous section | Table of contents | Next section |

|---|