As in the case of the priesthood, the tlatoani stood at the top of the military hierarchy. He was the commander-in-chief of the army, and his prowess as a warrior was of critical importance to the Aztec State. His first military task was to conduct a campaign as part of the coronation procedure. The structure of the Aztec military hierarchy goes as follows.

A supreme council of four noblemen governed the army, fulfilling a function roughly analogous to that of a general staff. These high officials were the tlacochcalcatl, the tlaccatecatl, the etzhuanhuanco, and the tillancalqui. At Tenochtitlan the members of the council of four were all brothers or close relatives of the tlatoani. The next levels of office classes could attain all but the highest positions. The two highest military societies or orders were theotontin "otomies" and the cuahchique. Only the most daring battlefield veterans could be admitted, for it was required to have takenmany captives and to have performed at least 20 deeds of exceptional bravery. All the soldiers in these societies were entitled to wear attire appropriate to their rank. Headgear, jewelry, cloaks, another accessories and emblems were strictly prescribed, and were personally handed to the warriors during special ceremonies. The war suits given to commoners were of animal skins, while those of the nobility were woven with feathers. On ritual occasions the warriors ate human flesh taken from the arms or thighs of their sacrificed captives. The great mass of common warriors wore body paint for identification and maguey cloth mantles, a breechcloth, and no sandals.

Military training for young boys began during their schooling. Martial exercises were actually conducted on the premises of the eagle and jaguar warriors' meeting houses, where youths assembled for instruction on the handling of arms, basic drill and maneuvers, and on discipline, military hierarchy, history, and battlefield lore. There was no standing army, instead, troops were called up for specific campaigns. The organization of the army was in units from local calpultin, or towns. In Tenochtitlan, each calpultin was required to contribute 400 men. Each unit marched under its own standards and was commanded by its own community leaders. The large basic unit of the Aztec army consisted of 8,000 men, roughly like a battalion. Long distance expeditions might involve as many as 25 units, equaling 2000,000 warriors, plus porters to carry supplies and equipment.

When the supreme council decided to carry out a campaign, orders were given to collect supplies. Tribute-towns were ordered to send maize cakes, maize meal, toasted maize, beans, chile, pumkin-seeds, pinolli, and salt. Individual warriors also carried as much food as they could supplement the basic rations. The first to depart were the scouts, followed by warrior-priests carrying sacred effigies, who marched a day ahead of the force. Then came the veteran warriors and members of the prestigious military orders. The third great contingent of warriors from Tenochtitlan followed, with units spaced out at regular intervals. Then came contingents from the many allied cities.

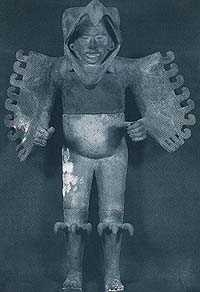

Eagle Warrior