Vasco da Gama - First voyage [1497/8 K ; ٩٠٢/٣ ﻫ]

Kusoma habari ya safari nyingine tumia kiungo :

Safari na vitendo vya Dom Francisco 1505 A.K / 910 A.H

PAGE 7a

I Previous page![]() I Full page List

I Full page List ![]() I Next page

I Next page![]()

From : Vasco da Gama's Journal.[ Portuguese Voyages 1498 - 1663]

Vasco da Gama bridge, outside Alcochete, Sébutal, Portugal. It is the longest bridge in Europe, with a total length of 17.2 km (10.7 miles). It opened on the 500th anniversary of the discovery by Vasco da Gama of the sea route from Europe to India. |

|

|

The old town of Alcochete,[see text]known for its salt pans, is located on the River Tagus. Its Arabic name dates back to the 7th.century. It was a royal retreat for Joāo I and Joāo II, and King Manuel was born here in 1469. |

Vasco da Gama's Journal -English version.

On Saturday we cast anchor off Mombasa but did not enter the port. No sooner had we been perceived then a 'zavra'[dhow] manned by Moors,came out to us; in front of the city there lay numerous vessels all dresssed in flags. And we, anxious not to be outdone, also dressed our ships, and we actualy surpassed their show, for we wanted in nothing but men, even the few whom we had being very ill. We anchored here with much pleasure, for we confidently hoped that on the following day we might go on land and hear the mass jointly with the Christians reported to live their under their own 'alcaide'[from the Arabic Alkadi, the judge] in a quarter separate from that of the Moors.

The pilots who had come with us told us there resided both Moors and Christians in this city ; that these latter lived apart under their own lords and that on our arrival they would receive us with much honour and take us to their houses. But they said this for a purpose of their own, for it was not true. At midnight there approached us a 'zavra' with about a hundred men all armed with cutlasses (tarcados) and bucklers. When they came to the vessel of the captain-major they attempted to board her, armed as they were, but this was not permitted, only four or five of the most distinguished among them being allowed on board. They remained about a couple of hours, and it seemed to us that they paid us this visit merely to find out whether they might not capture one or other of our vessels.

On Palm Sunday the king of Mombasa sent the captain-major a sheep and large quantities of oranges, lemons and sugar-cane, together with a ring, as a pledge of safety, letting him know that in case of his entering the port he would be supplied with all he stood in need of. The present was conveyed to us by two men, almost white, who said they were Christians, which appeared to be the fact. The captain-major sent the king a string of coral beads as a return present, and let him know that he purposed entering the port on the following day. On the same day the captain-major's vessel was visited by four Moors of distinction.

Two men were sent by the captain-major to the king still further to confirm these peaceful assurances. When these landed they were followed by a crowd as far as the gates of the palace. Before reaching the king they passed through four doors, each guarded by a doorkeeper with a drawn cutlass. The king received them hospitably and ordered that they should be shown over the city. They stopped on their way at the house of two Christian merchants, who showed them a paper (carta), an object of their adoration, which was a sketch of the Holy Ghost (1). When they had seen all, the king sent them back with samples of cloves, pepper, and corn, with which articles he allowed us to load our ships.

On Tuesday, when weighing anchor to enter the port, the captain-major's vessel would not pay off, and struck the vessel which followed astern. We therefore again cast anchor. When the Moors who were in our ship saw that we did not go on, they scrambled into a 'zavra' attached to our stern; whilst the two pilots whom we had brought from Mozambique jumped into the water, and were picked up by the men in the 'zavra'. At night the captain-major questioned two Moors [these were two of the four men who had earlier been captured in Mozambique], by dropping burning oil upon their skin, so that they might confess any treachery intended against us. They said that orders had been given to capture us as soon as we entered the port, and thus to avenge what we had done at Mozambique. And when this torture was being applied a second time, one of the Moors, although his hands were tied, threw himself into the sea, whilst the other did so during the morning watch.

About midnight two 'almadias'(2), with many men in them, approached. The 'almadias' stood off whilst the men entered the water, some swimming in the direction of the Berrio, others in that of the Rafael. Those who swam to the Berrio began to cut the cable. The men on watch thought at first that they were tunny fish, but when they perceived their mistake they shouted to the other vessels. The other swimmers had already got hold of the rigging of the mizzen-mast. Seeing themselves discovered they silently slipped down and fled. These and other wicked tricks were practised upon us by these dogs, but our Lord did not allow them to succeed because they were unbelievers.

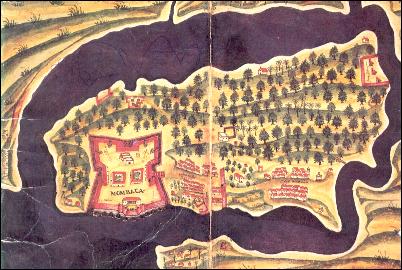

Mombasa is a large city seated upon an eminence washed by the sea. Its port is entered daily by numerous vessels. At its entrance stands a pillar, and by the sea a low-lying fortress. Those who had gone on shore told us that in the town they had seen many men in irons; and it seemed to us that these must be Christians, as the Christians in this country are at war with the Moors.

The Christian merchants in the town are only temporary residents, and are held much in subjection, they not being allowed to do anything except by the order of the Moorish king.

It pleased God in his mercy that on arriving at this city all our sick recovered their health, for the climate ('air') of this place is very good.

After the malice and treachery planned by these dogs had been discovered, we still remained on Wednesday and Thursday.

We left in the morning, the wind being light, and anchored about eight leagues from Mombasa, close to the shore. At break of day we saw two boats (barcas) about three leagues to the leeward in the open sea, and at once gave chase, with the intention of capturing them, for we wanted to secure a pilot who would guide us to where we wanted to go. At vesper time we came with one of them and captured it, the other escaping towards the land. In the one we took we found seventeen men, besides gold, silver, and an abundance of maize and other provisions; as also a young woman who was the wife of an old Moor of distinction, who was a passenger. When we came up with the boat they all threw themselves into the water, but we picked them up from our boats. The same day at sunset we cast anchor off a place called Malindi, which is thirty leagues from Mombasa. The following places are between Mombasa and Malindi, viz. Benapa, Toca,and Nuguoquioniete.

On Easter Sunday the Moors whom we had taken in the boat told us that there were at this city of Malindi four vessels belonging to Christians from India, and if it pleased us to take them there, they would provide us, instead of them, Christian pilots and all we stood in need of, including water, wood and other things. The captain-major much desired to have pilots from the country, and having discussed the matter with his Moorish prisoners, he cast anchor off the town, at a distance of about half a league from the mainland. The inhabitants of the town did not venture to come aboard our ships, for they had already learnt that we had captured a vessel and made her occupants prisoners.

On Monday morning the captain-major had the old Moor taken to a sandbank in front of the town, where he was picked up by an 'almadia'. The Moor explained to the king the wishes of the captain-major, and how much he desired to make peace with him. After dinner the Moor came back in a 'zavra',accompanied by on of the king's cavaliers and a 'sharif '(3): he also brought three sheep. These messengers told the captain-general that the king would rejoice to make peace with him, and to enter into friendly relations; that he would willingly grant to the captain-major all his country afforded, whether pilots or anything else. The captain-major, upon this, sent word that he proposed to enter the port on the following day, and forwarded by the king's messengers a present consisting of a 'balandrau' [a surtout worn by the Brothers of Mercy], two strings of coral, three wash-hand basins, a hat, little bells, and two pieces of 'lambel' [striped cotton stuff which had a large sale at the beginning of the African trade].

Consequently on Tuesday we approached nearer to the town. The king sent the captain-major six sheep, besides quantities of cloves, cumin, ginger, nutmeg, and pepper, as also a message, telling him that if he desired to have an interview with him he (the king) would come out to him on his 'zavra', when the captain-major could meet him in a boat.

On Wedenesday, after dinner, when the king came up close to the ships in his 'zavra', the captain-major at once entered one of his boats, which had been well furnished, and many friendly words were exchanged when they lay side by side. The king having invited the captain-major to come to his house for rest, after which he (the king) would visit him on board his ship, the captain-major said that he was not permitted by his master to go on land, and if he were to do so a bad report would be given of him. The king wanted to know what would be said of himself by his people if he were to visit the ships, and what account could he render them? He then asked for the name of our king, which was written down for him, and said that on our return he would send an ambassador with us, or a letter.

When both of them had said all they desired, the captain-major sent for the Moors whom he had taken prisoner, and surrendered them all. This gave much satisfaction to the king, who said he valued this act more highly than if he had been presented with a town. And the king, much pleased, made the circuit of our ships, the bombards(4) of which fired a salute. About three hours were spent in this way. When the king went away he left in the ship of one of his sons and a 'sharif', and took two of us away with him to whom he desired to show his palace. He, moreover, told the captain that as he would not go ashore he would himself return on the following day to the beach, and would order his horsemen to go through some exercises.

The king wore a robe (royal cloak) of damask trimmed with green satin, and a rich 'touca'(5). He was seated on two cushioned chairs of bronze, beneath a round sunshade of crimson satin attached to a pole. An old man who attended him as page carried a short sword in a silver sheath. There were many players on 'anafils', and two trumpets of ivory richly carved, and the size of a man, which were blown from a hole on the side, and made sweet harmony with the 'anafils'(6).

On Thursday the captain-major and Nicolau Coelho rowed along the front of the town, bombards having been placed on the poops of their long-boats. Many people were along the shore, and among them two horsemen, who appeared to take much delight in a sham fight. The king was carried in a palanquin from the stone steps of his palace to the side of the captain-major's boats. He again begged the captain to come ashore, as he had a helpless father who wanted to see him, and that he and his sons would go on board the ships as hostages. The captain, however, excused himself......

The town of Malindi lies in a bay and extends along the shore. It may be likened to Alchochete.(7) Its houses are lofty and white-washed, and have many windows; on the land side are palm groves, and all around it maize and vegetables are being cultivated.......

[Vasco da Gama's Journal, from Portuguese Voyages 1498 - 1663, ed. C.D.Ley

(1947), pp. 20-6 (London : Dent, 1947)

The account of Vasco da Gama's first voyage is taken from the annotated translation

made by Dr. E.G.Ravenstein. The original text was probably the log book of the Sao

Rafael written by a member of the crew, Alvario Velho. Dr.Ravenstein's translation

was originally published by the Hakluyt Society in 1898.]

Notes :

Vasco da Gama alikuwa msafiri maarufu, aliyefaulu kuliko wengineo hata

kuwa mtu wa kwanza kuvuka bahari kutoka Ulaya mpaka Uhindi kwa njia ya

kuambaa pwani Afrika. Aliacha Lisbon tarehe 8 July 1497 K [٩٠٢/٣ ﻫ] katika vyombo

vinne, hasa Sāo Gabriel, Sāo Rafael, Sāo Gabriel, Berrio, na meli ya vifaa.

|

Mombasa;1646 Mombasa;1646

|

Vasco da Gama - Safari ya kwanza [1497/8 K ; ٩٠٢/٣ ﻫ]

Habari zilizoandikwa katika Safari ya Kwanza ya Vasco da Gama kipindi cha kufutua pwani ya Afrika Mashiriki.

[Uzazi: Sines Vidigueira, Alentejo, Portugal, c. 1469 K/ ٨٧٣ ھ; ? Ufo: December 24, 1524 ; December 24, 1524 K/ ٩٤٠ ھ ; Kochi, India]

- Maandiko yametafsiriwa katika Kiswahilli kutumia kitafsiri kimechowekwa juu na kilichofanyikwa katika Kiingereza kutoka nakala asili ya Kireno (kujua zaidi tazama maneno yafuatayo baada ya kitafsiri kile).

Katika Daftari ya Vasco da Gama - Tafsiri ya KiswahiliSiku ya Jumamosi tulifunga nanga karibu na Mombasa lakini hatuingia katika bandari. Wakatuona tu, dau(1) moja lililopakizwa baharini na mamorisko, ilikuja kwetu; mbele ya mji vililala vyombo vyingi na vyote vilikuwa vimepambwa na bendera. Na sisi, twenye tamaa kutotaka kushindwa, sisi pia tulipamba meli zetu, na tuliiipita kweli tamasha yao kwa sababu hatukosekana ila watu, hata wale wachache tuliokuwa nasi wakuwa wagonjwa sana. Tulitia nanga hapo pamoja na furaha nyingi kwa sababu tulituamini bila shaka siku ya kesho yake tutaweza kushuka nchini na kusikia missa pamoja na wakristo ambao tulipata habari waishi hapo peke yake chini ya kadhi yao['alcaide'] katika mtaa wao mbali na ule wa mamorisko.

Nahodha waliokuwa wamekuja nasi walituambia kuna wote wawili, mamorisko na wakristo ambao walikaa katika mji huu : na hao wa pili walikaa peke yake chini ya wakuu wao na tungefika watatukaribisha na karama kubwa tena watatuchukua nyumbani kwao. Lakini walisema hivyo kwa kusudi yao yenyewe,na hakuwa na hakika. Usiku wa manane dau moja ilitukaribia na watu kama mia wote waliokuwa wameshika mikononi panga(2) na vigao. Walipofika chombo cha kapitani-mkuu walijaribu kukipanda, ndio na silaha zao, lakini hawakuruhusiwa ila wanne au tano wa waheshimiwa wao walipata kupanda juu. Walikaa saa mbili tatu hivi na sisi tulidhani walikuja kutuzuru kutafutia kwamba waweza kunyang'anya kimoja au kinginecho cha vyombo vyetu.

Siku ya Jumapili ya Mitende (3), Mfalme wa Mombasa alipeleka kapitani-mkuu kondoo mmoja , na mengi ya machungwa, malimau na miwa, pamoja na pete, kama kiwekeo cha amana, kumjulisha kwamba angeingia bandarini atayaletwa matakwa yake yote. Zawadi zilichukuliwa na watu wawili, karibu weupe, waliosema walikuwa wakristo ambayo ilionekana kuwa hakika. Kapitani-mkuu alipeleka Mfalme shada la ushanga ya kurejea zawadi, na alimjulisha yeye alikuwa na kusudi ya kuingia bandarini siku ifuatayo. Siku ile ile , meli ya kapitani-mkuu ilizuriwa na mamorisko waheshimiwa wanne.

Watu wengine wawili walitumwa na kapitani-mkuu waende kwa mfalme na wapatie zidisho la kusuduku haya matumaini ya salama. Walioshuka hao, walifuatwa na kundi la watu mpaka milango ya jumba la mfalme. Kabla ya kufika mfalme walipita milango minne, kila mmojayo ulilindwa na mbawabu aliyekuwa ameshika panga wazi mkononi. Mfalme aliwakaribisha na ukunjufu na alitoa amri waonyeshwe popote mjini. Njiani, walisimama kwa nyumba ya watajiri wawili wakristo waliowaonyesha karatasi (4), kitu walichoabudu, ambacho kilikuwa na mchoro wa Roho Mtakatifu. Walipomaliza ona yote, mfalme aliwarudishia pamoja na mifano ya karafuu, pilipili manga, na nafaka, vitu ambavyo alituruhusu kuvipakizia juu ya meli zetu.

Jumanne, wakati wa kung'oa nanga kuingia bandarini, chombo cha kapitani-mkuu hakugeuza demani kupata nafasi ya kutosha na kiligonga chombo kilichofuata kinyume. Kwa hiyo tulitia nanga tena. Mamorisko waliokuwa katika meli yetu walipoona hatukuendelea, walipanda kwa shida dau lililokuwa limefungashwa shetrini, na wakati ule ule nahodha wawili, ambao tulioleta kutoka na Mozambiki pamoja na sisi, waliruka ndani ya maji, na waliondoshwa na wale waliokuwamo katika dau. Wakati wa usiku kapitani-mkuu aliwauliza mamorisko wawili [hao ndio waliokuwa wale wawili miongoni mwa wanne, waliokamatwa mwanzoni katika Mozambiki], kwa kutoneka mafuta moto ya kuchoma juu ya ngozi zao, ili wakiri uchongezi wowote waliofanya kwa kusudia sisi. Hawa walisema amri ilikuwa imekwisha tolewa kutushika pale pale tutakapoingia bandarini, na hivyo kutoa kisasi kwa lile tulilofanya huko Mozambiki. Na walipopewa adhabu hii tena mara ya pili, morisko mmoja, hata ikawa mikono yake ilikuwa imefungwa, alijitupa mwenyewe baharini, na yule mwingine alifanya hivi hivi wakati wa kesha la asubuhi.

Karibu usiku wa manane 'almadia' mbili, zilizokuwamo watu wengi, zilitukaribia. 'Almadia' zilisimama mbali wakati watu walingia katika maji, baadhi ambao waliogelea kuelekea 'Berrio', na wengineo kuelekea kwenda 'Rafael'. Wale waliogelea mpaka Berrio walianza kukata amari. Mwanzoni, waangalizi walidhani walikuwa jodari lakini walipotambua kosa lao walipiga kelele kwa vyombo vyingine. Waogeleaji wengine walikuwa wamekwisha shika henza ya mlingoti wa galme, lakini walipoona kuwa wamevumbuliwa walijiteleza na walitoroka. Huu na ujanja mwingine mbaya ulifanywa kwetu na hawa mbwa, lakini Mola yetu hakuacha hao kufaulu kwa sababu walikuwa watu bila imani.

Mombasa ni mji mkubwa umeokaa juu ya kilima ambacho hulambwa na bahari. Bandari yake yaingizwa kila siku na vyombo vyingi. Mlangoni wake husimama nguzo, na palipo bahari boma moja inayokaa chini. Wale walioshuka nchini walituambia kwamba mjini waliona watu wengi fungwa mapingu ; na sisi tulidhani walikuwa wakristo, kwa sababu wakristo katika nchi hii wafanya vita na mamorisko.

Watajiri wakristo ambao wamo mjini ni wahamaji wa wakati tu, na wako chini ya utii ukubwa, hawaruhusiwi kufanya lolote ila kuwa kuamriwa na Mfalme Mmorisko.

Ilipenda Mungu katika rehema yake kwamba tulipofika mji huu wagonjwa wetu wote walipata nafuu, kwa sababu hewa ya mahali hapa ni mzuri sana.

Baada ya uchongezi na uovu uliokusudia na hawa mbwa uliogunduliwa, tulikaa hivyo Jumatano na Alhamisi.

Tuliondoka asubuhi, na upepo ukawa mwanana, tulitia nanga ligi nane kutoka Mombasa, karibu na pwani. Wakati wa alfajiri tuliona mashua (5) mbili ligi tatu hivi upande wa demani katika bahari wazi, na mara moja tulifuata mradi kuzikamata, kwa sababu tulitaka kujipatia rubani atakayeweza kutuongoza popote tulipotaka kwenda. Wakati wa jioni, tulikuja na mojazo na tuliitwaa, ndiyo ile nyingine ikatoroka kwenda nchi kavu. Ile tuliokamata ilikuwamo na watu kumi na saba, tena na dhahabu, fedha, mahindi mengi na vifaa vyingene; pia na msichana mmoja aliyekuwa mke wa mzee mmorisco mheshimiwa, na aliyekuwa abiria. Tulipofika kando ya mashua, wote waliruka binafsi ndani ya maji, lakini sisi tuliwavutia kwetu na mashua zetu. Siku ile ile magharibu, tulifunga nanga karibu na mahali paliitwa Malindi, ambapo ni ligi thelathini kutoka Mombasa. Mahali fuatapo ndipo baina ya Mombasa na Malindi, yaani, Benapa, Toca, na Nuguoquiniete.

Jumapili ya Pasaka mamorisko tuliochukua na chombo chetu walituambia kwamba katika mji huu wa Malindi kulikuwapo vyombo vinne vya wakristo wa Uhindi, na ingawa itatufurahisha kuwachukua hao kule , wataweza kututilia viongozi wakristo, badala hao, na kila kitu tulichokuwa na kuhitaji, hata maji, miti na vinginevyo. Kapitani-mkuu alitamani sana awe na rubani ya nchi yenyewe, na baada ya kuzumgumza juu ya jambo hilo na wafungwa wake mamorisko, alifunga nanga mbele ya mji, mbali ligi nusu hivi kwa nchi kavu. Wenyeji wa mji hawakujaribu kupanda vyombo vyetu kwa sababu walikuwa wamekwisha jua kwamba tumekamata chombo kimoja na waliokuwamo ndani wafungwa.

Asubuhi, siku ya Jumatatu, kapitani-mkuu alipelekeza mmorisko mzee ufukoni mbele ya mji, pale ambapo alipakizwa na 'almadia' moja. Mmorisko alieleza kwa Sultani matumaini ya kapitani-mkuu na kadiri kubwa ndiyo aliyetaka kusuluhia naye. Baada ya chakula cha kutwa, mmorisko alirudi ndani ya 'zavra', pamoja na askari mmoja wa farasi wa Sultani, na msharifu mmoja ; alileta na pia kondoo tatu. Mitume hawa waliambia kapitani-mkuu kwamba mfalme atapata furaha kuaminisha naye, na kuingia katika hali ya urafiki ; tena, atamjalia kwa nia kamili kapitani-mkuu vyote vinavyopatikana katika nchi yake, hata marubani au chochote kingine. Aliposikia hilo,kapitani-mkuu alituma habari ambayo ataingia bandarini siku ifuatayo na alipeleka mbele na mitume wa Sultani 'balandrau' (6), shada la ushanga mbili, bakuli tatu za kunawa mikono, kofia moja, makengele matatu, vipande viwili vya 'lambel' .(7)

Kutokana na jambo hilo, Jumanne, tulikaribia mji. Mfalme alipeleka kapitani-mkuu kondoo sita, tena, vipimo vya karafuu, jira, tangawizi, kungumanga, na pilipili, pamoja na taarifa kumwambia ingawa alitaka kuzungumza katikati zote wawili, naye (mfalme) alikuwa tayari kutoka kwake katika dau lake, na kapitani-mkuu anaweza kumkutana naye juu ya chombo.

Siku ya Jumatatu, baada ya chakula cha kutwa, alipokaribia vyombo dau la mfalme, kapitani-mkuu aliingia mara moja chombo chake kimoja, kilichokuwa kimepambwa vizuri, na maneno mengi mema yalizungumzwa muda vilipolala kandokando. Mfalme alipoalikia kapitani-mkuu aje kupumzika nyumbani kwake, na baadaye (mfalme) atakuja kuamkia yeye melini, kapitani-mkuu alisema hakuruhusiwa na bwana wake kwenda nchi kavu, na ingawa angefanya hivyo, itapelekwa ripoti mbaya yake. Mfalme alitaka kujua nini itaongezwa na watu wake angalienda yeye kuzuru melini, na ataweza kuwaeleza namna gani hao? Halafu, aliuliza jina la mfalme wetu, ambalo lililoandikiwa , na yeye alisema tuliporudi atapeleka balozi nasi, au barua.

Walipokwisha sema yote waliotaka kusema, kapitani-mkuu aliwaitia Mamorisko wale aliyechukua yeye wafungwa, na alirudishia wote. Hilo liliridhisha mfalme mno, naye alisema yeye alithamini jambo hilo zaidi kuliko ingawa angepata zawadi ya mji. Na mfalme,akawa na furaha sana, alizunguka duara ya meli zetu, ambazo zilipiga mizinga ya kumsalimia. Karibu saa tatu zilipita hivyo. Alipoondoka mfalme, alikwenda katika chombo cha mtoto wake mmoja pamoja na msharifu, na aliwachukua wawili wa sisi naye, wale ndio aliotaka kuwaonyesha jumba lake . Tena, alimwambia kapitani kwamba kama yeye hawezi kutelemka katika bara, yeye mwenyewe atarudi siku ifuatayo mpaka pwani, na ataamrisha askari wake wa farasi wacheze mazoezi.

Mfalme alivaa joho-kifalme la hariri lililokungwa na atlasi ya rangi majani na kilemba cha mali (8). Alikuwa ameketi juu ya vyeti viwili vya shaba nyeupe, chini ya mwavuli duara ya atlasi nyekundu uliokazwa juu ya mti. Mzee mmoja aliyemngojea kama mtoto wake mtumishi alikamata upanga mfupi futikwa katika uo wa fedha. Walikuwa wachezaji wengi wa zumari (9), na siwa mbili za pembe za michoro, ukubwa wa mtu mzima, zilizopigwa na tundu kandoni zao, na zilizolingana sauti na zumari.

Siku ya Alhamisi kapitani-mkuu na Nicolau Coelho walienda na makasia mbele wa mji, na sitahani ya mashua zao ndefu iliwekwa mizinga. Walikuwa watu wengi ukingoni, na pamoja nao wapanda farasi wawili walioonekana kuwa na furaha mno katika mchezo wa kupigana. Mfalme alitwekwa begani ndani ya mahmili kutoka daraja la mawe la kasri yake mpaka mbavuni mwa mashua za kapitani-mkuu. Aliomba tena kapitani aaje nchi kavu, tena alikuwa na babaye ambayo alitaka kumwona, na hata yeye na watoto wake walikuwa tayari kupanda juu ya meli zao kama wawekwa amani. Lakini, kapitani- mkuu, aliomba amsamehe kutofanya....

Mji wa Malindi upo juu ya hori, na hutandama urefu wa ukingo. Hufanana na Alcochete(10). Nyumba zake zaenda mpaka juu na zimepakwa chokaa, na zina madirisha mengi; upande wa bara, kuna vichaka vya minazi, na kila mahali pale hulimwa kupanda mahindi na mboga.....

Maelezo mafupi:

PAGE 7a

I Previous page![]() I Full page List

I Full page List ![]() I Next page

I Next page![]()

Safari na vitendo vya Dom Francisco 1505 A.K / 910 A.H

| © M. E. Kudrati, 2006:This document may be reproduced and redistributed, but only in its entirety and with full acknowledgement of its source and authorship |

|---|