Egypt

Pottery was one of the earliest art forms

undertaken by the ancient Egyptians. This piece from the Predynastic period

(5000 bc-3000 bc) is decorated with ostriches, boats, and geometrical designs.

In the 5th millennium bc Egyptian potters made graceful, thin, dark, highly

polished ware with subtle cord decoration. The painted ware of the 4th

millennium, with geometric and animal figures on red, brown, and buff bodies,

was not of the same high standard. Dynastic Egypt was famous for its faience (to

be distinguished from the later European ceramics of that name). First made

about 2000 bc, it is characterized by a dark green or blue glaze over a body

high in powdered quartz, somewhat closer to glass than to true ceramics.

Egyptian artisans made faience beads and jewelry, elegant cups, scarabs, and

ushabti (small servant figures buried with the dead).

Greece

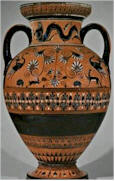

The Northampton Vase is an example of Greek

vase painting from the late 600s and early 500s bc. The shape of this vase is

known as an amphora, one of six standard shapes used in pottery at that time.

The mythological creatures and delicate, floral designs reflect the Greek

interest in Oriental imagery, and these forms are augmented with white and brown

highlights.

The fashioning and painting of ceramics was a major art in classical Greece.

Native clay was shaped easily on the wheel, and each distinct form had a name

and a specific function in Greek society and ceremonial: The amphora was a tall,

two-handled storage vessel for wine, corn, oil, or honey; the hydria, a

three-handled water jug; the lecythus, an oil flask with a long, narrow neck,

for funeral offerings; the cylix, a double-handled drinking cup on a foot; the

oenochoe, a wine jug with a pinched lip; the crater, a large bowl for mixing

wine and water. Undecorated black pottery was used throughout Greek and

Hellenistic times, the forms being related either to those of decorated pottery

or to those of metalwork. Both styles influenced Roman ceramics.

Even in the Bronze Age, the Greeks took advantage of oxidizing and reducing

kilns to produce a shiny black slip on a cream, brownish, or orange-buff body,

the shade depending on the type of clay. At first, decorative designs were

abstract. By the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1500 bc), however, stylized forms from

nature appeared. By the Late Bronze Age, plants, sea creatures, and fanciful

animals were painted on pots of well-conceived shape by the Mycenaeans, who were

initially influenced by Cretan potters. Athenian geometric style replaced the

Mycenaean about 1000 bc and declined by the 6th century bc. Large craters in the

Geometric style, with bands of ornament, warriors, and processional figures laid

out in horizontal registers, were found at the Dipylon cemetery of Athens; they

date from about 750 bc.

Attic potters introduced black-figure ware in the early 6th century. Painted

black forms adorned the polished red clay ground, with detail rendered by

incising through the black. White and reddish-purple were added for skin and

garments. Depictions of processions and chariots continued; animals and hybrid

beasts were also shown (particularly in the Orientalizing period, roughly 700 to

500 bc), at times surrounded by geometric or vegetal motifs. Such decoration was

always well integrated with the vessel shapes, and the iconography of Greek

mythology is clear. Beginning in the 6th century, the decoration emphasized the

human figure far more than animals. Favorite themes included people and gods at

work, battle, and banquet; musicians; weddings and other ceremonies; and women

at play or dressing. In some cases, events or heroes were labeled. Mythological

and literary scenes became more frequent. Potters' and painters' names and

styles have been identified, even when they did not sign their works.

Red-figure pottery was invented about 530 bc, becoming especially popular

between 510 and 430. The background was painted black, and the figures were left

in reserve on the red-brown clay surface; details on the figures were painted in

black, which allowed the artist greater freedom in drawing. The paint could also

be diluted for modulating the color. Secondary colors of red and white were used

less; gold sometimes was added for details of metal and jewelry. Anatomy was

rendered more realistically, and after 480, so were nuances of gesture and

expression. Although Athens and Corinth were centers for red-figure pottery, the

style also spread to the Greek islands. By the 4th century bc, however, it

declined in quality. Another Greek style featured outline drawing on a white

ground, with added colors imitating monumental painting; these vessels, however,

were impractical for domestic use.

Iran and Turkey

This mug was made in 16th-century Turkey

during the Ottoman Empire. It is earthenware, with a white underglaze and blue,

purple, and red overglazes. The floral and calligraphic designs are similar to

those found in most Islamic art. This piece is part of the collection of the

Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The Seljuk dynasty that ruled Iran, Iraq, Asia Minor, and Syria in the 12th and

13th centuries found substitutes for porcelain, and the Iranian cities of Rayy

and Kāshān became centers for this white ware. Another fine Seljuk type was

Mina'i ware, an enamel-overglaze pottery that, in its delicacy, imitated

illuminated manuscripts. Kāshān potters, after the 13th-century Mongol

conquests, used green glazes influenced by Chinese celadons. Cobalt-blue glazes

appeared in Iran in the 9th century but later fell out of use. They were taken

up again in the 14th to the 18th century in response to the popularity of

blue-and-white ware with Chinese and European clients.

İznik was the center for Turkish pottery. There slip-painted pieces influenced

by Persian and Afghanistani ware predated the Ottoman Turks' conquest of the

region. Later, between 1490 and 1700, İznik ware displayed decorations painted

under a thin transparent glaze on a loose-textured white body; in its three

stages the designs were in cobalt blue, then turquoise and purple, then red.

During the Safavid dynasty, Kubachi ware, contemporary to İznik pottery, was

probably made in northwestern Iran, and not at the town of Kubachi where it was

found. Characteristic Kubachi pieces were large polychrome plates, painted

underneath their crackle glazes. Gombroon ware, exported from that Persian Gulf

port to Europe and the Far East in the 16th and 17th centuries, featured incised

decorations on translucent white earthenware bodies. Copper-colored Persian

lusterware was fashionable in the 17th century, as was polychrome painted ware.

In general, Islamic pottery was made in molds. Shapes were either Chinese

inspired or were the basic shapes of metalwork. In addition to lusterware, the

most creative work was the manufacture of tiles for mosques.

Pottery at a Glance|East Asian Pottery|Pre Colombian Pottery