To our left, the frozen white expanse of snow- and ice-covered Hudson Bay. To our right, snow-covered lakes and thin stretches of spruce.

To our left, the frozen white expanse of snow- and ice-covered Hudson Bay. To our right, snow-covered lakes and thin stretches of spruce.

"Fred, where is north?"

--Robert Frost, "West-Running Brook"

First of all, sit quietly with eyes closed.

Inhale deeply. Then exhale.

Repeat.

Do this for as long as necessary.

I want to write this carefully, to think, to remember, to express myself clearly, choosing the best of all possible words.

Why do I keep going away from the city? Why do I keep going north? Am I seeking something? Am I running away?

Iím still beginning to continue to make sense of it all. Or continuing to begin.

Silence compels me. Cold, quiet, elemental places beckon.

I sense something beyond the borders, something in back of beyond.

Do I exaggerate?

"I am not afraid that I shall exaggerate the value and significance of life, but that I shall not be up to the occasion which it is," Thoreau wrote to his friend Harrison Blake, April 3, 1850.

Itís time for new traditions.

Day 1

Iíve driven all morning, hurtling northwest at a ridiculous speed in my rattly old car, past Downer and Detroit Lakes, Minnesota, across the Red River into North Dakota, then due north, past some of the flattest stretches of land Iíve ever seen, white fields like vast snow-covered lakes, where a few small islands of trees sometimes appear, protecting farmhouses and barns.

Manitoba license plates say "Friendly Manitoba," not "Finally Manitoba," as I first think.

On the Canada side of the border, I stop and buy some money. Two hundred dollars in greenbacks gets me two hundred thirty-nine dollars and two cents in Canadian cash. One of the pennies is a collectorís item, Iím told. It dates from Canadaís centennial, 1967.

Imagine Canada before it was Canadian.

Continuing north, I drive past St. Jean Baptiste, Manitoba ("Soup bean capital of Canada"), past Riel Industrial Park (named for the 19th century Mťtis rebel whose grave is in Winnipeg), and past Ste. Agathe (about which I know nothing).

Going kilometers per hour instead of miles per hour makes all the diff-air-ahnss. In Winnipeg, after a seven and a half hour drive, I find the train station, relieved that my noisy wagon made it here without breaking down. Picking up my ticket and checking my duffel, I learn the station has no long term parking, so I drive around till I find a nearby hotel, an old glitzy one, the Hotel Fort Garry, where I go inside and pay to park my car for nine nights.

Now I sit indoors, hungry, at an 8-table "Oriental" restaurant with a Korean-sounding name: Kim Long.

I have nearly three hours before the train boards. I have a slight headache. I have my wits about me.

Four hundred sixty miles of driving today. Whatís that--740 kilometers? A long way to come in order to eat the weirdest pad thai Iíve ever tasted, salty and barbecue-y and not at all sweet.

Winnipeg has a human population of 618,000, but it doesnít seem so big.

After eating I walk to Mondragon Books, which turns out to be a collectively-run vegan cafť, serving soups, salads, and sandwiches, besides offering a small selection of radical books and magazines. Mondragon is located in a building donated during the Depression for use as Young Menís Hebrew Association headquarters. In its window, hanging from a clothes line: Punk Planet, Herbivore, Utne, Cineaste, Anarchy, and Colorlines.

A bus goes by as I wait to cross Main Street. Its destination: SOUTHDALE.

Back at the big, old, nearly empty station, a few of us throwbacks to a different era sit, reading and writing, as a security guard takes up space uselessly.

Tout le monde ŗ bord!

They donít actually call "all aboard!" these days, it seems. Maybe thatís only because there are so few people on this train.

What sort of person would willingly travel from a moderate climate to the sub-arctic cold of Churchill, Manitoba, in February?

The rear car on VIA Railís "Hudson Bay" tonight is a sleeper named Chateau Dollard. My car is a castle.

The high temperature today in Churchill was -25 degrees Fahrenheit.

The train from Winnipeg heads northwest through eastern Saskatchewan, before bending back northeast to The Pas, and then north to Thompson and Churchill. Itís a scheduled 36-hour ride.

The timetable for "The Hudson Bay" includes names of dozens of tiny communities.

In Manitoba: Portage la Prairie. Glenella. Laurier. Ochre River. Dauphon.

In Saskatchewan: Togo. Kamsack. Mikado. Canora. Endeavor. Hudson Bay.

I fall asleep around Glenella, perhaps.

Mikado?

Day 2

Back in Manitoba, I wake as the train approaches The Pas, the farthest north Iíve ever been.

Who are we when we sleep?

The sun isnít up yet, the trainís running a little late, and nothing is what it appears to be. So what?

Why isnít the town named Le Pas, I wonder? In any case, itís time for fresh air and a short walk.

The Manitoba flag is red with the Union Jack in one corner (the so-called "Red Ensign," formerly Canadaís national flag) with the addition of "Armorial Bearings" centered in the right half, a shield topped by St. Johnís Cross (red on white) with a bison on a green field below it.

Itís impossible to make out these details with the flag flapping in the wind, but Iíve done subsequent research.

It feels good to stretch. I slept in a drawer last night.

Now I breakfast in a dining car where Iím the sole customer. An old couple vacated before me. The last call for breakfast was delivered by attendant Carmelle in fluent English and French. Petit dťjeuner sounded good.

Kraft cremeux peanut butter for my toast. Oui, this is familiar. Cíest bon. Then again, Jíai faim.

Outside the train windows: white and black spruces, tall and narrow. White birch, white snow, white sky. An eagleís nest up high.

Snow sculptures in the woods, ghosts of the past. Tracks in the snow: Who made them?

More Manitoba hamlets pass. (Whoís passing who?) Tremaudan. Orok. Atikameg Lake. Finger. Budd.

Manitoba: main boat.

Where the buffalo roam no longer. (We pass bison in a corral.) Mid-morning: a car waiting at a crossing. Thereís a highway this far north? Vraiment, there is. Highway 10.

Hudson Bay Railway line construction began at The Pas in 1920, but the Churchill section wasnít completed until 1929, according to the Field Guide to the Manitoba Region Geological Survey of Canada, Miscellaneous Report 53.

It was slow going. "The last 200 km are through muskeg."

I like muskeg on my eggnog.

The railway "requires constant, expensive maintenance," the survey says. A branch line at Gillam was abandoned prior to 1982. "Some parts of the track are suspended in mid-air as a result of thermal erosion and streamflow around culverts, whereas other parts are like a roller-coaster track."

"Notice the tripole supports for the hydroline along the track." Yes, Iíve been noticing. But what is a hydroline, exactly? I donít see anything that looks like itís carrying water.

A freight train hauling snow-covered logs lumbers past. At first I think the train Iím on is moving, until I look out the left-hand windows. The difference between left and right depends on which direction one faces. Face the opposite direction, and left and right change places.

Now the sky has cleared. Bright sun, blue sky, snow several inches deep on the tracks as I look out the rear window. Trees flocked with white clumps.

Thanks to Carmelle for a slice of pumpkin cheesecake after my veggie burger. "Itís compliments," she says. Perhaps a reward for eating the garnish, kale.

Riding the Polar Express, bound for Goose Jaw, the trees get smaller and thinner, like weeds. Birches disappear.

Zero is a number. Nowhere is a place.

This here is the "the Hudson James lowland ecosystem."

More Manitoba villages: Cormorant. Rawebb. Wekusko. Ponton. Button. Pipun. Wabowden. La Perouse. Hockin. Thicket Portage. Sipiwesk. Pikwitonei. Amot. Pit Siding. Munk. Nonsuch. Wivenhoe. Kettle Rapids. Bird. Charlebois. Weir River. Thibadeau. OíDay. Back. MíClintock. Cromarty. Chesnaye.

I fall asleep during this litany, protected by the wings of Bird, perhaps.

Itís like counting backward from a hundred.

Day 3

Where am I?

In Manitoba, of course. Lamprey. Bylot. Tidal. At most of these locations the train halts only on request. Whistle stops.

And then, like that, weíre at the end of the line.

The town of Churchill and its train terminal are set on a strip of land that juts northeast between the Churchill River estuary and Hudson Bay. At the tip of the strip is Cape Merry.

I find my duffel, wrest it from an overeager hockey dad who thinks itís his sonís, and go inside to call the Churchill Northern Studies Center to ask for a ride. The Centerís assistant director answers, and almost before Iíve hung up Dianne has driven 26 kilometers to town for me.

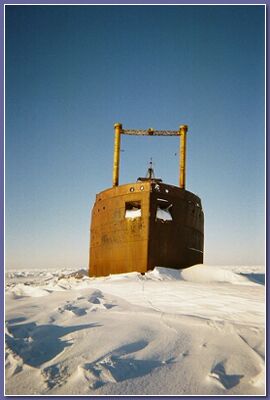

Crossing the tundra, driving east away from Churchill and back toward the Center, Dianne points out the bear jail, the airport (site of former military base Fort Churchill), and the shipwreck Ithaca.

To our left, the frozen white expanse of snow- and ice-covered Hudson Bay. To our right, snow-covered lakes and thin stretches of spruce.

To our left, the frozen white expanse of snow- and ice-covered Hudson Bay. To our right, snow-covered lakes and thin stretches of spruce.

The Churchill Research Range was Canadaís only permanent rocket launch facility, operating from the 1950s through the 80s. Founded in 1976, the Churchill Northern Studies Center (CNSC) bought the place for $1 and moved here after the rocket scientists left.

Thereís still a launch pad on the site and other evidence of what the place used to be.

Welcome to home away from home, a building with barred windows.

This time of year the Center is quiet. A cook and a program director are bunking here now, along with an eight-person elderhostel class ("Northern Lights and Astronomy"), a teacher, two researchers, and two volunteers. The dormitory could accommodate four times that many.

A sign in a bathroom reads

In the afternoon I go out to have a closer look at things. And a closer listen.

Churchill is situated in an ecotone, a transition area between two adjacent ecological zones. In this case, receding woodland and beginning tundra.

What does this ecotone sound like? Entirely, utterly, totally silent at times. Until a raven speaks. Until snow crunches underfoot. Until the wind finds something to howl against or through. Ecotonic music, minimal but never ending.

Silence is the same in every language.

Yes, but here the silence is amplified.

Some silence speaks clearly.

Where are the polar bears? The adult males are out on the edge of sea ice this time of winter, sealing in Hudson Bay. Pregnant females--or new mothers--are denning here on land.

Nanook is the Inuit name for the worldís largest carnivore. The label more frequently used in these parts is Wapusk, Cree for "white bear." Females can weigh up to a half ton, but males are behemoths, growing up to 1500 pounds and ten feet tall. Their feet may be wider than adult humansí are long. Wapusk lives free in only five countries: Canada, the U.S. (Alaska), Denmark, Norway, and Russia, but really only in one country: Wapuskia.

What does it mean that some polar bears have lost their fear of humans?

Scientists at the CNSC have been watching bear-human interactions each fall when so-called tundra buggies full of tourists and photographers make their way over ice directly to where polar bears can be found. From July through November, they can be seen "lounging around inland," writes German photographer Norbert Rosing in his book The World of the Polar Bear.

The Hudson Bay Post reports that a researcher was attacked by a bear near Churchill in November. Wapusk has come to view humans benignly.

I wonder what the bearsí own media report about the two-legged ones whoíve been tattooing Wapuskians on the inside of their lips.

David Baronís germane The Beast in the Garden reports on human-cougar interaction, especially in and near Boulder, Colorado, where habituated cougars, increasingly unafraid of humans, graduated from snatching pet dogs and cats in the 1980s to preying on people. The book also describes political debate about wildlife management, from its philosophical premises to pragmatic action (and inaction) in a human society where such debate is often polarized.

Polar bears walk on--and swim in--a sea of tears.

We should not call this planet Earth, some say, but rather Ocean. Most of its surface is covered with water.

The weight of a female sea bear (Ursus maritimus) can drop to just over 200 pounds during a long, cold winter, Rosing says. Infants are tiny, less than two pounds.

The adult white bears can run 30 mph over a short distance, faster than the speediest human sprinter. Picture that.

Humans might run here just to stay warm. Churchill is located at 58 degrees, 44í N., the same latitude as Stockholm and Oslo. The townís official population is a little over a thousand, but that number swells in summer when residents are outnumbered by visitors, and dwindles in winter.

Iím here at the Center this week with an elderhostel instructor from Oakbank, Manitoba, a Formula One racing enthusiast, an astronomer/cosmologist, a motorcyclist, and a maker of crabapple wine. Thatís one person: Roger Woloshyn, a.k.a. Starman.

Iím also here with an ambient sound collector and composer, a speaker of Dutch and Flemish, a bookstore worker from Ann Arbor, and someone thinking about Novanglian secession from the union. Meet Brent Wetters.

The director of the CNSC is a wildlife biologist who grew up in small-town northern Saskatchewan and who until recently had never been south of Missoula, Montana. (Then he went to Long Beach, California.) Introducing Mike Goodyear.

If I stay here long Iíll be speaking Canadian in no time. Itís quite a PRO-cess. Not so much humans a-GAYNst polar bears, as all of us in it together, eh?

The avuncular, white-mustachioed cook, Don Cleaver, is eager to have new people with whom to talk.

Is it possible to be private and quiet together with others? It is, I learned recently, attending a Friends meeting for the first time.

Once upon a time I was so morbidly shy that I would take refuge in closets.

Once below a time, things have changed.

Iím still sometimes given to taking French leave, but I love people, and it excites me somehow to be unafraid.

Caution: Fearlessness can lead to horrible failures, misunderstandings, honest words that maybe ought to be withheld.

"Make your failure tragical by the earnestness and steadfastness of your endeavor, and then it will not differ from success," Thoreau wrote to Blake, December 22, 1853, but...

I wonder about this.

All my life is in the ellipses. At dinner the elderhostel folks drink wine. Three of them sing drinking songs afterward, probably dating from the 30s and 40s. Their happiness is contagious and charmingly off-key. Looking on with bemusement: a pair of researchers here at the Center studying wind. Sergeyís English is so-so. Changís is negligible. They both fit right in.

Elderberry wine?

"There is no world for the penitent and regretful." (Thoreau again, April 24, 1859.)

Sometime after dinner I climb up a ladder from a second floor classroom into a Plexiglas dome atop the building, once used for monitoring rocket launches. Up in the sky an arc of pale light curves, horizon to horizon.

Aurora borealis is beginning its nightly show.

Some of us don parkas and boots, and go outside.

Over the course of uncounted minutes, I watch the sky, transfixed.

Spanning east and west, the band of light brightens, then divides into first two and then three long strands. Curving, twisting, the light dances, rises like smoke, shimmers like curtains, shines like a beacon, ever shifting.

I stand beholden.

Peter Davidson writes in The Idea of North (University of Chicago Press, 2005), "The Finn and Sami belief was that the aurora is caused by a fox running across the snowy fells of the north with its tail sweeping the snow and sending up radiances, Ďfox fires,í into the sky. Other Finnish interpretations see the aurora as the foxís tail itself swishing the sky, or--a vision of polar abundance--understand it as a reflection of the scales of the innumerable fish that swim in the Arctic seas."

"In the Northern Islands lying between Scotland and Norway," he goes on, "the streamers of the aurora are called the merry dancers, an acute observation of the resemblance between the shifting veils of light and garments lifting and folding as the dancer swings round in the turns of the dance."

Some articles mention how people claim to have heard the lights.

Why not? Aurora borealis: visual theremin music.

I swear I can even smell the lights, a singed, charcoal-y, dark green electrical scent, though maybe Iím dreaming.

In his journal on September 7, 1851, Thoreau wrote

The northern lights... have become a crescent of light crowned with short, shooting flames, --or the shadows of flames, for they are sometimes dark as well as white.... Now the fire in the north increases wonderfully, not shooting up so much as creeping along, like a fire on the mountains of the north seen afar in the night. The Hyperborean gods are burning brush, and it spread, and all the hoes in heaven couldnít stop it. It spread from west to east over the crescent hill. Like a vast fiery worm it lay across the northern sky, broken into many pieces; and each piece, with rainbow colors skirting it, strove to advance itself toward the east, worm-like, on its own annular muscles. It has spread into their choicest wood-lots. Now it shoots up like a single solitary watch-fire or burning bush, or where it ran up a pine tree like powder, and still it continues to gleam here and there like a fat stump in the burning, and is reflected in the water. And now I see the gods by great exertions have got it under, and the stars have come out without fear, in peace.

Fearless stars.

I love the sky. A part of me lives there with my seven sisters.

What dreams come to those with their heads in the heavens?

Day 4

Today I spend some time weeding and organizing a reading room at the Center. In the process I learn about such publications as Up Here (covering Canadaís north) and Bear News.

In the afternoon I tag along when the Centerís program director drives the elderhostel crew to visit a dog sled camp near town.

The air temperature today is in the vicinity of thirty below. At a certain degree, Fahrenheit and Celsius no longer disagree.

No water stays unfrozen for long outdoors in this weather. Dave Daley makes soup for his dogs to keep them hydrated.

So many dogs, so many personalities. Some shy away when I approach their kennels. Some rush to greet me, stand on their hind legs, and loll their tongues as if wanting not only hugs but kisses.

So many dogs, so many personalities. Some shy away when I approach their kennels. Some rush to greet me, stand on their hind legs, and loll their tongues as if wanting not only hugs but kisses.

In the warming tent a white puppy makes its way underfoot, occasionally being lifted by human hands and fondled. The puppy survived a wolf attack recently and also has a yellow patch of fur on its back where it was singed while walking under the stove.

Tea time: moose meat and bannock.

By the time I ride on the back of a sled, the 8-dog team is losing steam, trotting on level stretches, but struggling up hills. Musher Dave stops to give them a rest.

The dogs are training for an upcoming race to Churchill from Arviat, up the coast in Nunavut.

This place requires special words to describe it. Moraines are accumulated material carried and deposited by glaciers. Eskers are ridges or mounds formed from deposits at the ends of glacial rivers.

Churchill was once 6000 feet under ice, it is said. The Hudson Bay coastline has moved from 100 kilometers south.

Who lives here? Inuit, Cree, and Chipewyan people. And people whose ancestors have been in the area for fewer generations. A parvenu or two.

In Canada, "the non-conformists go north (as they do in the British Isles, and Japan)," writes Davidson.

About Glenn Gouldís radio series by the same title, Davidson says, "There is never any pretence that the north answers questions... it only intensifies the experience of the individual who goes there." The showís concluding point, he asserts, is that the northern wilderness is "a constant challenge, a more positive reason for unity and the maintenance of unity than any external enemy."

Maintenance is not just the keeping of something in good working order. Literally itís now-ness.

Davidson writes of William Morrisí voyage to Iceland in the 1870s, "Morris approached Iceland... ready to be thrilled... looking almost for an otherworld." Morris himself reported, "It was quite up to my utmost expectations as to strangeness: it is just like nothing else in the world."

"Iíd like to get away from earth for awhile," said Robert Frost in "Birches."

Picture springtime in this place that is now covered with snow and ice. In the Churchill area 422 vascular plants, 107 so-called exotic weeds, 269 lichens, and 178 mosses can be found.

There are even two species of frogs. Currently frozen.

Find them.

When I grow up Iím going to be a bryologist.

The Churchill bird count of June 9, 2004 included American tree sparrow, house sparrow, robin, northern flicker, and mallards. It might have been Minneapolis, if we stop the list there.

The mean monthly normal temperature here in February: -22 F. daily low, -7 F. daily high.

Tonight we watch the northern lights again. The first to go outside, Iím just in time to see a bright yellow meteor falling through the aurora.

In the southern hemisphere, aurora australis, the southern lights, mirror the aurora borealis.

Who holds the mirror?

"The power to control nature corrupts." So says Starman.

My friend Noel Peattie died recently, but a part of him is here with me tonight. Noel was an amateur astronomer from childhood on. Hereís a poem from his collection Western Skyline (Regent Press, 1995)

Solomon Said

For three things my heart rejoices:

yea, four things I could watch forever

A shooting-starís light spilling across the constellations

the ripe ripple of a wheat field gold under west wind

the full-swelling sails of a ship,

drinking Pacific air

and a proud young daughter of Earth,

in jeans and sweater,

walking slowly,

but, please, Lord,

not

too

slowly.

Noel was also a meteorologist, yes?

His death: an unhappy surprise.

Hereís what FranÁois Villon has to say about that

Princes are destined to die

And so are all others who live

Whether they rage at this or tremble

So much blows away on the wind.

Platitudes or poetry? Read more of Galway Kinnellís translations of Villon and decide for yourself.

Help me root out dead metaphors.

Help me celebrate unexpected connection, unexpected happiness.

Help me mourn unexpected severance, unexpected anguish.

Help me watch the sky.

I have learned this week that Inukshuk are Inuit stone cairns.

Two of the eight-person elderhostel group came all the way from Gulfport, Mississippi, bravely, and two from Mt. Airy, North Carolina. The woman from Gulfport said she called the Center every day for a week before coming, worried, seeking encouragement from whoever answered the phone, including Don (who responded "Iím just the cook!"). She said she freezes in Gulfport when itís 20 degrees Fahrenheit, but sheís been toasty and comfortable here.

How can we adapt to dramatic changes so quickly?

Thoreau wondered about a friend with whom he had parted, writing in his journal, August 24, 1852, "I have the utmost human good-will toward that one, and yet I know not what mistrust keeps us asunder."

Can we sing praise of disconnection without being ironic?

It was not a new subject for the Concordian contrarian. "Methinks our estrangement is only like the divergence of the branches which unite in the stem," he wrote on December 31, 1851, hopefully.

Belugas come into the estuary of the Churchill River to calve.

They come and they go.

So many partings, more departures than homecomings it seems, though surely this canít be true.

"I long to be...the empty, waiting, pure, speechless, spectacle," Mary Oliver writes in "Blue Iris."

I long to be.

Day 5

Having finished organizing the reading room, I turn my attention to the more scholarly library collection.

Some books on the shelves here

* Caribou & Muskoxen Response to Helicopter Harassment, Prince of Wales Island, 1976-77.

* Guide to the Identification of Plant Microfossils in Canadian Peatlands.

* Wildflowers of the Churchill and Hudson Bay Region. (400 pages)

* The Thick-Billed Murres of Prince Leopold Island. (350 pages)

* Assessment of the Arctic Marine Environment: Selected Topics.

* Microbiological Degradation of Northern Crude Oil.

* Illustrated Glossary of Periglacial Phenomena.

* Identification & Ageing of Holarctic Waders.

* American Arctic Lichens. (390 pages)

* The Rare Vascular Plants of Manitoba.

* Seals and Sealing in Canada.

* Permafrost Terminology.

* Mate Choice in Plants.

Three periodical titles

* Arctic Insects News.

* Cold Regions Technical Digest.

* Terrae Incognitae: The Annals of the Society for the History of Discoveries.

Other sundry printed matter:

* The Failure of Ice (a research paper by L.W. Gold).

* American Society of Mammalogists Membership List, May 1973.

* Muskeg Impedance Factors Controlling Vehicle Mobility (a reprint from Canadian Oil and Gas Industries, July 1958).

Also here: other works on glaciology, permafrost, polar exploration history, arctic and sub-arctic botany and zoology. And, surprising me, a pristine-looking three-volume 18th edition of Dewey Decimal Classification (dating from 1971).

My vocabulary increaseth. Here are two definitions from the Longmans Dictionary of Geography, 1966:

"In Canada, an undrained basin filled with bog moss and peat."

"Fine-grained wind-sorted and wind-deposited material laid down away from the margins of the great ice sheets of Pleistocene times."

Respectively, those describe muskeg and loess, more or less.

And hereís one from Permafrost Terminology: "Alas-- a circular to irregular lowland...from which the originally large ice centers (up to 80% by volume) has essentially disappeared resulting in a lowering of the ground surface..."

Ice disappears, alas.

How does water freeze? Let me count the ways. Aufeis. Aggragational ice. Buried ice. Cave ice. Epigenetic ice. Ice wedges. Interstitial ice. Pore ice. Et cetera.

Few are called, many are frozen.

This afternoon I hike over the sea ice of Hudson Bay, toward the hulk of an abandoned ship visible from afar. The Ithaca grounded in 1960 and was left to rust.

This afternoon I hike over the sea ice of Hudson Bay, toward the hulk of an abandoned ship visible from afar. The Ithaca grounded in 1960 and was left to rust.

As I walk toward the ship, it grows smaller and smaller. I put my head down and count two hundred strides, then look up to find that the ship has completely disappeared.

Since I have to hike back at least as far as Iíve already come, Iím only going half tilt. Still, Iím starting to sweat, so I stop for a while to admire snow sculptures.

On the sea ice, these snow shapes appear, some two feet high, some over my head, like dollops of whipped cream, or as if waves had been flash frozen. Gazing northward to the endless edge, for countless minutes I simply exist without a single thought in my head.

Iím losing my mind. And I donít mind.

"Lose something every day," poet Elizabeth Bishop advised.

Lose out, find out.

"Snowdrifts freeze into drums," Alice Angus writes in "Near Real Time" (Proboscis Cultural Snapshots Number Five). Walking on this hard snow atop airier snow makes for a hollower thud under oneís feet.

Underneath some of the snow: hibernating seeds.

This isnít really north. Itís the center of the world.

The silence is spectacular.

Nothing but snow and ice in all directions. The tiny ship appears once more, then once again shrinks as I move toward it. Can a lesson be learned from this illusion?

During another rest from my plodding, I hear the ice pop and snap all around me.

I am not the boss of all.

One raven flies out to the ship, keeping watch.

Yes.

"And the sun goes down in waves of ether

in such a way that I canít tell

if the day is dying, or the world,

or if the secret of secrets is in me again."

So wrote Jane Kenyon, translating Anna Akhmatova.

A look at a map later indicates that I hiked at least 10 kilometers.

The place where the ship ran aground is called Bird Cove. I saw a bird but no cove, land and sea not being easily distinguished.

Whatís for dinner, Don?

Tonight the northern lights are less than stunning. How jaded Iíve become.

Brent plays some of his musical composition, a DVD with images and ambient sound from his previous winter trip here, titled "Saturn and Jupiter."

Itís good to be with people who reject cultural kitschification. Humans who keep languages alive. Poets. Thinkers. Listeners. Savers of seeds. Artisans. Guardians of strange, wild, beautiful public secrets.

Day 6

At dawn I look at a thermometer. The temperature indoors, just inside a window, is 47 degrees Fahrenheit. Outdoors itís -27.

This place could use a cryometer, for crying out loud.

On a morning walk, heading south and west, I notice tracks of foxes, ptarmigans, and a hare, but see only a single raven and a gray jay.

All my relations.

"As if seeing were all in the eyes... [S]eeing depends ever on the being," Thoreau noted, January 12, 1852.

For lunch I see mashed potatoes, french fries, and boiled potatoes.

For dessert: a book.

Iím reading more about mountain lions this afternoon. If Iím ever killed by a cougar, if my heart is someday carved out and devoured, remember this: "He loved cats."

Think this: "He knew some joy in his life. He knew some pain. He was privileged to see and smell the northern lights, and to walk on Hudson Bay."

A high school student from Vermont arrives at the Center, volunteering with Earthwatch. Ruth is a cross country skier, canoeist, cellist, lover of northern places.

At dusk a handful of us drive to town, stopping first at the airport to pick up boxes of game and fish shipped here via Kivalliq Air which serves Churchill and points north.

North to Nunavut. v To some this is south. Churchill lies well below the Arctic Circle.

After we drop two people off for dinner at Gypsyís (known to some for their green apple fritters), three of us visit the townís only bar that is open tonight, before Brent departs via rail. v Sleeman Honey Brown Lager. The bottle has no label except for a small one on the neck. The clear glass makes it look like home brew, except that the bottle is embossed (if thatís the right word). v Do I want a glass? I do.

I also order the national dish, poutine, that turns out to be made with white cheese (not curds) and bland gravy. Itís not the best, but Iím hungry and it slides right down.

Back at the Center, Heather, the program director, has started a batch of bannock. I help stir, knead, and roll it out. Later I smell it in the oven, take a peek, and catch it before it gets too brown.

Itís the last evening for the six remaining elderhostel participants. Two are on their way back to the States, Laura (who a year ago was using a walker) and Gretchen, a former serious marathoner and retired historian who Heather refers to as "the spry one."

In after-dinner conversation Heather uses the word "regime" to describe the U.S. government. I tell that her the word isnít used much that way in the States, but that sheís right, of course.

Ruth and I succeed in completing a jigsaw puzzle.

Day 7

Overcast sky in the morning. Then blizzardy: snow and blowing snow with some drifting. The temperature rises above zero Fahrenheit, but it feels much colder facing the stiff west wind.

Then the sky clears. Particles of snow sparkle in the air like sunbeams.

"How full of the creative genius is the air in which these are generated! I should hardly admire more if real stars fell and lodged on my coat." So Thoreau wrote in his journal, January 5, 1856.

"What a world we live in! where myriads of these little disks, so beautiful to the most prying eye, are whirled down on every travellerís coat, the observant and the unobservant, And they all sing, melting as they sing of the mysteries of the number six,--six, six, six."

Jim Northrup writes in his "Fond du Lac Follies" column in The Circle, "During the day when the wind picks up a bit I can see the snow blowing off the branches. It comes down in shimmering sheets of snow. The falling curtains remind me of the waves that pulse through the jiibayag niimiíidiwag, northern lights."

I upload some photos taken by Brent and elderhostel participant Robert, and post them on a web page, via dial-up Internet access. The uploading process is akin to drinking peanut butter through a straw.

Early afternoon Ruth and I go for a walk, southwest again, past a tall pile of rocks Iíve already climbed and dubbed Mt. Gravel, past ptarmigan tracks, past a lake, tramping through drifts.

Early afternoon Ruth and I go for a walk, southwest again, past a tall pile of rocks Iíve already climbed and dubbed Mt. Gravel, past ptarmigan tracks, past a lake, tramping through drifts.

Itís lovely and bright. We see sun dogs, bright spots on either side of the sun, and then an entire parhelion.

We also see wing marks imprinted where a bird took off from the snow. Ptarmigan ptracks beneath a ptamarack.

Hereís one big stone standing out of the ground, covered with orange acne.

I take a photo of Ruth, so swaddled that her parents and sister may not recognize her.

Iím using a couple of disposable cameras this week, not wanting to shlep my big one. Iíd like to get my fingers on a digital camera.

Trees: scrawny white and black spruce here south of the Center. Tamarack, few taller than six feet.

Back at the parking lot, protected by a snow drift, one arctic hare sits at attention, motionless, white except for black ear tips and eyes. After a while it resumes nibbling a bush.

This evening twenty-three children are visiting from town, a scout troop with four or five adults attached. Theyíre here for dinner, a lesson in night sky watching, and an overnight stay in the dorm.

Heather has unplugged the pop and candy machines, and put up "OUT OF ORDER" signs.

The crew eats hot dogs, soup, and butterscotch pudding. Then I wash their dishes, as smaller hands rinse and load items to be sterilized.

Mid-evening, Roger goes outside with the children who react to the darkness and cold with high-pitched shrieking. A few of them pay attention as he points out the Big Dipper, Orion, Sirius, Castor and Pollux, Cassiopeia, and Saturn.

Heather says the elderhostel crew called for dibs on "Bottom bunk!" while the kids called dibs on "Top bunk!"

One boy was afraid that if he slept on a top bunk heíd fall, and if he slept on the bottom heíd be fallen upon. So he slept on a couch.

Fear of bunks.

Another Earthwatch volunteer arrives, all the way from London, England. Kate has a Strine accent and in fact sheís from Down Under.

Up under. Asunder. Alice in wonder.

Scout troop, trout scoop.

Day 8

A blustery day, snowing. One more walk on the frozen tundra, alone.

"[C]old and solitude are friends of mine," Thoreau bragged.

Whatís up with this sign in Japanese and English ("Lake Iwago"), sprouting from the snow?

Iíve done what I can with the library here for now. I make myself useful doing dishes and helping unload a shipment of food, then shower and pack my bag.

It seems too soon to go.

Don encourages me to raid the fridge and pack myself some food for the train.

After supper, Dianne and her daughter Alanna give me a ride to town where they live, and let me accompany them to the public library, located in the town center along with the school, hockey arena, swimming pool, and town offices.

The library has an exhibit of Inuit artifacts, including owl lures, and a ring and pin game made of bone (akin to ball-in-cup). And hereís a newspaper rack full of papers dated May 2004, nine months old. For a few seconds I wonder if Iíve been caught in a time warp.

Taking a walk around the building, I ask directions to a rest room and get a blank look. "Wash room" is the thing to ask for here.

Not that I want to wash. Or to rest, for that matter.

Alanna chides me for locking the truck door. Vehicle theft is unknown in Churchill. Where would you go? (Doors are also left unlocked so people might escape into them from the cold or from bears.)

This is a small town. Dianne tells me that veterinarians come from Thompson twice a year, and that barbers and hairdressers come a little more often.

I sit in the station now. Only six other passengers wait for the train.

All aboard?

Now Iím ensconced in the Chateau Cadillac, higher off the ground than I was in my Chateau Dollard roomette.

I read for a while, then pull my bed down from the wall, unlike before when I slept in a drawer.

Day 9

Sitting in the dining car, picking ham out of my scrambled eggs, peering out the window at animal tracks, thinking Iíve just seen wolf tracks intersect with those of a hare, I hear the attendant say, "While youíre looking, keep your eyes open for a wolf. Thatís when Iím looking for. Oneís been seen between mile posts [something or other] and [something or other]."

"About 150 pounds." Seen with a deer bone.

Hunger drives wolf from woods.

I hadnít realized till now that there are mileposts along the tracks. How fast are we traveling? Do the math. (It seems that typical cruising speed through these parts is about 40 mph.)

Thereís a road plowed right over a river. (Weíre passing Pikwitonei.)

And thereís the moving blue shadow of a train going over a bridge. This train I ride.

Many rivers to cross.

Itís a bright day, but I turn my attention to a dark book. The Lost Island: Alone Among the Fruitful and Multiplying, by Alfred van Cleef, first published in Dutch in 1999, describes the authorís three-month stay on remote Amsterdam Island in the South Indian Ocean, a tiny French outpost where small groups of men (never women) have researched weather, flora, and fauna--from microscopic rotifers to feral cattle--since 1949. Something like a Southern Studies Research Center.

For Van Cleef, son of Jewish Holocaust survivors (and resident of Amsterdam, Holland), the voyage is an obsession that begins with eight years of persistent attempts to gain required permission from a minor French official, a venture somehow connected to the authorís failed relationships with women.

Van Cleef describes the islandís transient but intimately connected community. "There were many facilities, but few personnel," he writes. The sole doctor was also veterinarian, dentist, garbage collector, dishwasher, psychologist, cleaner, and shopkeeper.

Amsterdam is more remote than Churchill. "The island didnít even have a boat of its own. ĎWhere would you go?í the district chief said. ĎThe nearest land is nearly two thousand miles away, over the roughest seas on earth."

Van Cleefís existential quest, it seems, is to reach one place, one moment, somewhere wild, where everything is right and makes sense. The author writes of having attained a remote and rugged spot on the island from which he could see ocean all around, where he stood "face-to-face with infinity." Goal achieved: "This was what I wanted: This was my life."

Getting away from it all, Van Cleef no longer sensed the loneliness heíd felt in his home city. On this extinct volcano, living in near squalor, coping with mud, rutting fur seals, and dubious food, he writes, "Here I felt fully connected to the life around me: rocks and wind, albatrosses and seals, biologists and meteorologists."

Why am I pulled to the perimeters?

Will I ever learn? What can I know here and now?

I wonder.

Midday the train stops for an hour or so in Thompson, an opportunity to explore.

A hand-lettered sign on the train station door:

A mining town, Thompson is the third largest community in Manitoba, population 14,385.

I walk along a road, choosing the same direction that cars and pick-ups are moving, and in fifteen minutes come to a retail district that includes a Wal-Mart and a McDonalds, signs of decay.

In a combination doughnut shop and deli, I procure a sandwich and two muffins to go, lunch and dinner at once.

Blessed are they who hunger and thirst.

Walking back to the train, hereís evidence that Iím in a new bioregion: cattails.

The joy of language: While reading this week Iíve learned thereís a word for death by bleeding: exsanguination. The same term might be used when someone is cut off from a family.

Mid-afternoon. Sky gone totally overcast. Blowing snow. Here I am, sheltered from the cold, riding along in my 4x6í cell.

In the village of Wabowden a sign is posted on a small building:

In the village of Wabowden a sign is posted on a small building:

Not much business there today, I guess.

So many things I donít know. Most of which I donít even know I donít know.

It takes chutzpah to be an activist. Yet who wants to be a passivist? (Thanks to Jenna Freedman for this word.)

Weíre constrained in a yes-no society where making an immediate decision shows youíre a real "take charge" person, confident, a leader. But binary thinking is infantile thinking. Wet-dry, hot-cold. Thereís more to life than that.

When things go wrong, Iím often too quick to speak, as if true words from the heart are a panacea. Better if I had a time-delay between my brain and tongue. Better I heeded more often Thoreauís words to Blake:

"Let things alone; let them weigh what they will; let them soar or fall. To succeed in letting only one thing alone in a winter morning, if it be only one poor frozen-thawed apple that hangs on a tree, what a glorious achievement!"

Consider the lilies.

Picture the saguaro. As Jimmy Santiago Baca writes:

"I donít hear the cactus explaining his-self,br>

nor the mimosa tree chattering in the front yard why it is

the color it is,

nor the water as it streams down hill

telling me it has to do so..."

Here on the edge of the northern desert, trees imperceptibly get taller as the train moves south. This morning they were mere sticks in the ground, weed-like and absurd. Now some are 20-30 feet high.

Outside in the snow: tracks to and around bushes, intersecting tracks, straight lines of tracks heading into woods, curving tracks, tracks along the edge of a tree line, animal tracks crossing railroad tracks.

"If you look closer it's easy to trace the tracks of my tears."

So sang Smoky.

What time is it? I donít know.

"Observe the hours of the universe, not of the car," Thoreau advised.

Have I run out of good questions?

After dusk the train arrives at The Pas where I go for a short walk, enjoying fresh air. Heading toward a DQ sign, I find a liquor store open where I buy a bottle of ale marked $1.79 or so, plunking down about twice that amount for it.

The Pas seems like a bustling city, but its population is under six thousand.

Day 10

The vast snowy plain north of Winnipeg could be Hudson Bay but for the islands of tree-surrounded farms that dot it at intervals.

Fog covers the ground this morning, backlit by a bright rising sun.

A single road alongside. Powerlines. No visible horizon.

Coming into town at 8:47 a.m. according to my feckless watch. (Never does it report the real, true time.)

Look at all the buildings and cars. Fast food joints. Church steeple. Cupola with something gold shining at the top. Twelve- or thirteen-floor apartment buildings. "Winnipeg Winter Club." (Curling?) Wet streets.

Civilization to be sure. But I donít feel particularly happy to be heading back home. I donít look forward enthusiastically to meetings, nor to deadlines, and have no particular craving to sleep in my own bed nor to do laundry.

I do look forward to a run. And to tasting real cheese.

Home is where I am. And where my people are: in Minneapolis, but also in downtown Manhattan, among the paloverdes of Scottsdale, on a farm outside Columbus, in the hills of West Redding, and at the foot of the Abajo Mountains.

How we labor, chopping wood, casting rubber, teaching English, gathering eggs, herding words, sorting mail, like an orchestra with no conductor.

Carmelleís French, spoken one more time over the intercom, reminds me of Montreal, as the train passes a snow-covered driving range.

Weíve reached the end of the line, five passengers and five employees. "Les gens qui vous transportent"--people moving people. Thatís the slogan of VIA Rail.

My bag was the only one checked. I shlep my gear across the street and hand my parking stub to a valet at the hotel.

Now Iím on the road, heading south through Winnipeg.

Signs for gas, 82.9 a liter. Cigarettes: over eight bucks a pack.

At the border I sell $161 Canadian cash for $124 in greenbacks. Iím a poorer person now. But Iím richer for knowing there is a town called Minto in North Dakota. Itís almost due east of Minot.

In Minnesota, speeding south, I see the brightest red row of dogwood osier against blue sky and also realize that I am back in the land of highway patrol. Nine days without any visible signs of law enforcement until now.

What does it mean, this travel back and forth? Itís as though Iím a snake trying to get rid of my dead skin.

"I pine for one to whom I can speak my first thoughts; thoughts which represent me truly," Thoreau wrote, August 24, 1852.

First thought, best thought? Thoreau lived among the pines.

"Many a cry for help is made with a snarl." So says aphorist John E. King.

I wonder as I wander. Is there such a thing as too much truth telling? If so, what times call for circumspection?

"Unfettered truthfulness--what psychiatrist Willard Gaylin calls Ďtruth dumpingí--can be every bit as cruel as habitual lying," Ralph Keyes asserts in his book The Post-Truth Era. "Few want complete honesty from others without exception. Truth is a two-party proposition: one to tell, one to hear."

What do you think? Now that youíve come this far with me, how much circumspection do you want?

Could we make beautiful music together, a banjo-tuba duet?

Careless and carefree: Note the distinction.

Memories come back to me. Have I been taken advantage of? Have I failed? If so, how? And regardless, what now?

We never know where the seeds of our words and actions may be carried. They may somehow latch onto a person we donít even know, like how a dog passing through weeds can catch burrs in its fur and transport them. Somehow the seeds may take purchase in a bit of soil somewhere and germinate and grow without our knowing it.

"Maybe" seems such a tenuous word on which to pin faith.

Iíve glimpsed fields of flowers growing far away that looked so familiar.

None who have given and loved have done wrong.

We shouldnít allow ourselves to sour.

The line about not casting pearls before swine seems to suggest that some humans donít deserve the best effort and attention. I venture that everyone needs caring attention, but that none of us has the sole responsibility to provide unlimited care for any one person, much less for all.

Even when it comes to families, we share responsibility. Our time and energy is finite. We have ourselves to nurture and we have the gift of choice, the wonderful freedom to turn in the direction of our passions, enthusiasm, and toward the people and activities that uplift us, energize us, and allow us to grow and be more fully human.

To care both widely and locally, expecting no results, can be challenging.

Encouragement helps. Trust your aspiration.

Howard Zinn writes in You Canít Stay Neutral on a Moving Train about his civil rights movement work in the 1960s, about how his students at Spellman--young African American women--went to Atlanta Public Library where they were denied equal services, and how they persisted in requesting such titles as Thomas Paineís Common Sense and John Stuart Millís On Liberty. Eventually this small action had an effect--the library services were integrated.

Martin Luther Kingís Why We Canít Wait describes how ordinary people in Alabama in 1963 faced fire hoses, attack dogs, arrests, and beatings, for trying to register to vote, for walking arm-in-arm in the street, or simply for witnessing othersí courageous nonviolent direct action.

These events took place in the United States just a little over forty years ago.

The knowledge of actions such as this are one reason to get out of bed each morning. When we despair and feel forlorn, thereís still worthwhile work waiting patiently for us, as long as we have brains, hearts, and hands. And when we breathe deeply and look up, when we re-engage in that work, knowing weíre not alone, it can be like coming home.

"[I]f the doors of my heart/ever close, I am as good as dead," Mary Oliver writes in "Two Kinds of Deliverance."

I vow to keep my eyes and heart open. I want to live and foster life, to love and be loved, to give and to receive, to reflect light and to absorb darkness, continually, steadfastly, gratefully, with as much grace as I can muster, with all due seriousness, with joy, and with laughter.

For those to whom "heart" is an empty metaphor, let me be more clear. There must be at least a thousand species of love. I have felt love of the world, weltliebe--the sense of being a tiny, happy, integral part of a system of trees, rivers, mountains, ants, amoebae, humans, colors, sounds, and feelings. I have felt love of vocation, of feeling caught up rightly in the creative spirit that blurs distinction between work and play. I have felt familial love, unconditional caring that comes close enough to real understanding, the rays of which are a healing or protective balm.

I have known responsible love: caring, decent, compassionate, continuing feelings of mutuality, of being part of the same ecology, of putting myself in anotherís shoes, answering "yes" without asking why. I have known love that bears heaviness, empathy, and tolerance, slowly, patiently, without grudge. Iíve known love that hurts.

I have experienced loving friendships that have continued multilaterally over decades, love that does not assume anything other than that connection always continues, even during times of quietude, together-and-apart.

I have known love where there were sparks, laughter, good energy, inspiration, enlightenment, and great joy. I have felt the love of connecting each moment to the next, honestly, warmly, gently, openly, with those around, whoever they may be on a particular day. And I have seen reassuring love on even my darkest days: treesí love of soil and sky, birdsí love of trees and pond, and egretsí love of fish.

If there are some with whom I feel both calm and energetic, in whose presence I feel more alive, awake, and aware--and there are--for this I am thankful.

And what about self-love? Are we integrated? What is the status of the civil rights movement within?

Learn from Wapusk. Watch and listen quietly. Monitor balance. Wait patiently. Test the ice.

"Beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things."

Exist.

Wait patiently for nothing in particular.

Arctic insects, sled dogs, Colorado cougars, drinkers in the corner bar, pilgrims circumambulating Mount Kailash, poutine eaters, people struggling with illness, canyon wrens, proud mothers, those who are fathers in their imaginations only, all those whoíve been forsaken, all those who are found, we are all connected. "Do you think there is anything not attached by its unbreakable cord to everything else?" Mary Oliver asks this in "Upstream," an essay published in Orion magazine.

The world is large and we are small and our bodies ever-changing, tender, and mortal.

Do we dare imagine otherwise?

The canyons and sirens of the city await.

Grand Marais, northern Minnesota, November 2004

Climbing Ktaadn, New England, May 2004

You Are Here, northern Minnesota, November 2003

Porcupine Mountains, Michigan's Upper Peninsula, May 2003

Baptism River, northern Minnesota, March 2003

Cairn Free, southern Utah, November 2002

Red Cliff, south shore of Lake Superior, May 2002