|

Theories and opinions on why so much modern prog doesn't measure up – by Scott Hamrick |

|||||

|

The golden age of progressive rock ended 25 years ago. As much as some prog enthusiasts may not want to admit it, and despite all that has happened in progressive rock since then, the vast majority of the best progressive rock was recorded in the first half of the ‘70s. That was a long time ago. The short-lived and unlikely nexus of political, social, economic, technological and artistic forces that combined to create an atmosphere in which progressive rock could evolve and reach critical mass has long since evaporated, but progressive rock has never entirely disappeared. In recent years it has actually experienced a resurgence in popularity. Almost every classic progressive rock band from Emerson Lake & Palmer to Agitation Free has reformed and released new albums in the last decade. Numerous new prog bands also have been formed. Some, like Spock’s Beard or Transatlantic have even begun to approach widespread commercial success. We can now buy albums by some of these bands in national record store chains. Progressive rock festivals like NEARFest, Baja Prog and Prog Day have been popular (though not always financially successful) events, drawing bands and audience members from around the world. Progressive rock album review websites are all over the internet; and in the United States we have two major, long-running underground progressive rock magazines – at least one of which is now available at some of the same aforementioned big record and book stores. But something’s missing. The golden age of prog has not really been resurrected. Yes, we have experienced all the trappings of a prog rock revival, except what matters most – a lot of good progressive rock.

Is it just me, or has there actually been very little interesting progressive rock to come out of the last 10 years? Sure, there are some good prog bands releasing good albums, but these days there are far more bad prog bands releasing boring, low quality, derivative albums than good bands adding albums to the ranks of the classics of the genre. Surely the good/bad ratio in the ‘70s was not as bad as it is today. Who in the last decade has even approached the artistic scope and vision of the classic early ‘70s albums by bands like Yes, King Crimson, Genesis, Gentle Giant, Magma, Banco, PFM and a host of others? In your humble editor’s opinion, almost no one. Even the minor classic European bands who only released one or two albums in the ‘70s are rarely rivaled these days. Think of your top five absolute favorite progressive rock albums. How many of them were recorded in the ‘70s? Unless you’re a staunch neo-progger, I’ll bet at least four of them are golden oldies. Why is this? It’s not that there aren’t plenty of bands out there trying their best to be the next big thing in prog rock. There has been a revival underway for ten years, but how many of the last decade’s crop of progressive bands will be counted among the greats in another 10 or 20 years? Discipline? The Flower Kings? Spock’s Beard? No way. Are these among the best progressive rock has to offer? Keyboards and long guitar solos a classic prog band do not make. So, what are modern prog bands doing wrong, and why? There are several reasons most modern prog bands simply don’t measure up to the masters of yesteryear. Let’s start with the most obvious. Much of what passes for progressive rock today suffers from one giant flaw. It’s filtered through 20 years of heavy metal. What this means is that prog rock that displays this tendency is (on purpose or not) strongly influenced by heavy metal. Many of these bands seem to believe they’re creating progressive rock in the traditional mold, but the fact is that they’re far too influenced by the double-bass-drum and guitar-hero histrionics of the post-Van Halen era to be true descendants of progressive rock. When Van Halen’s first album was released in 1978, rock guitar and rock music in general were forever divided in two. There was the pre-Van Halen era, in which rock guitarists all tried to sound different, and the post-Van Halen era, in which far too many guitarists tried to sound like Eddie Van Halen. This is a theory of my own creation, but I think there is plenty of evidence for its legitimacy. If you’ve ever heard the solo guitar piece called “Eruption” from Van Halen’s first LP, you’ll see what I mean. It’s one minute and 43 seconds of lightning speed string shredding and complex finger tapping techniques, the likes of which the rock-and-roll world had never seen previously. Not since Jimi Hendrix had burst onto the scene in 1967 had any rock guitarist made as deep an impact on his fellow musicians. Who played guitar like Van Halen before 1978? No one I know of. Who played like that afterward? Almost everyone, especially those playing hard rock or heavy metal. Just listen to Rush’s Permanent Waves album. It was released on January 1, 1980 – just long enough after the first Van Halen LP for its influence to have manifested itself in Alex Lifeson’s own playing. Listen to the guitar solos. You won’t hear any finger tapping, dive bombing or such high speed picking on A Farewell to Kings or any Rush album prior to it, but there it is loud and clear on “Spirit of Radio,” “Natural Science” and “Freewill.” We can thank Eddie Van Halen for that. His playing was so revolutionary that it caused an already established, artistically and commercially successful rock guitarist like Alex Lifeson to alter his playing style. Likewise he affected almost all other rock guitar throughout the ‘80s. This is even more true in heavy metal. Van Halen-style guitar – and to a lesser degree some of the other things that go along with heavy metal (strained, high-pitched vocals, relentless double-bass-drum assaults, etc.) – were grafted into the existing heavy metal vine upon the arrival of Van Halen, and they have become so prevalent and inescapable since then that it almost seems as if these tendencies were always a part of heavy metal. These post-Van Halen characteristics have even seeped into and tainted prog rock during the last 20 years, and by increasing amounts. The problem with this is that these techniques were over-used and abused in 1980s hard rock. How can progressive rock, which bred such guitar innovators as Robert Fripp, Allan Holdsworth, Steve Howe, Daevid Allen; and which once prided itself on rejecting typical blues-rock formulas now continue to embrace such played-out wankery? Now we even have prog metal as practiced by the likes of Dream Theater, Pain of Salvation, Mastermind and scores of groups on the Magna Carta label. Just flip through the pages of Progression magazine and you’ll see more ads for progressive metal bands (complete with fantasy album covers depicting cartoonish looking warriors wearing Viking helmets, carrying broadswords and riding winged horses, etc.) than you can vomit at the sight of. Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with progressive metal. There are even a couple of Dream Theater pieces that still blow my mind. If prog metal is what people want to listen to, that's fine. But how progressive is the majority of this stuff? Let’s be honest with ourselves. Much of what passes for “progressive” metal is really just plain old metal. Metal had to go underground a few years ago when grunge took over. (Ever noticed the similarities between the prog/punk revolution of the late ‘70s and the metal/grunge revolution of the early ‘90s? That’s another essay altogether.) Once the evil metal heads and their million-note-a minute guitar solos had been vanquished by the righteous but talentless grungesters, metal found itself in much the same place as prog was in 1976. Shrinking audiences forced metal bands to do one of two things – go with the flow by cutting the length of their hair and their guitar solos (Metallica is a good example) or go underground. It seems likely that many of the new metal bands that came of age in the ‘90s stayed relatively underground and found a modicum of success among progressive rock fans because those audiences were the only ones who were still willing to listen to displays of gratuitous instrumental virtuosity. It is my view that heavy metal and progressive rock really have little in common. There are indeed some common traits. The aforementioned instrumental virtuosity has been held in high regard by both camps consistently. Freedom to compose lyrics covering a wider variety of topics than typical rock music is another similarity. Aside from these two things, however, the two styles are mostly different. Rarely in typical heavy metal will one hear acoustic or feminine passages, classical/unusual instruments, keyboards played as anything more than subtle chordal backdrop, odd time signatures, jazz chords and rhythms and a host of other things that are so inherent to progressive rock. Metal is typically a simpler, more banal form of music. There are exceptions, of course, and some prog metal bands have truly managed to lift heavy metal to higher planes. But more often than not, the amalgamation of prog and metal leads to superficial “prog” ornamentation – like guitar solos played in classical scales and the occasional inclusion of odd time signatures – being draped across what is basically an unmovable heavy metal framework. Metal is based on two or three basic traits. Take one or two of them away and you no longer have heavy metal. Prog rock, on the other hand, can come in a wide variety of combinations of characteristics and still be recognizable as prog. Compare Univers Zero with Marillion. They have little in common, but they are both considered progressive rock. You won’t find that kind of diversity among metal. Therefore, when prog and metal are thrown into a pot and stirred, metal usually must dominate if it is to be still categorized as metal. If the fast guitar solos, strained, high pitched vocals or galloping double-bass drum rhythms were removed and replaced with something else, it wouldn’t be metal anymore, progressive or otherwise. Thus, in order to be called metal, music must fall within these relatively narrow parameters, which, inherently, keep the music from being very progressive at all. True progressive rock and true heavy metal are almost mutually exclusive, and attempts to evenly mix the two are usually unsuccessful. Edward Macan’s book Rocking the Classics (1) further discusses the similarities and differences between prog rock and metal very well. The next trait that many less-than-stellar modern prog bands exhibit is the tendency toward producing “watered down” prog. This is a very common weakness in many modern progressive rock bands and is very easy to spot. In the early days of progressive rock, the pioneers were searching for ways to expand rock’s vocabulary and scope. Bands like The Moody Blues, King Crimson and Soft Machine combined rock’s elements of power and rhythmic propulsion with influences they found in more highly developed forms of music, namely classical and jazz. This led to an increase in complexity on almost every level; rhythmic, melodic, harmonic, lyrical and instrumental. Classical and neo-classical composers like Bach, Mozart, Copland, Bartok and Stravinsky; and jazz artists like John Coltrane and Miles Davis were the inspiration for these musicians as much as any previous rock bands. This is why early progressive rock bands often achieved such a high level of compositional and instrumental virtuosity. Some of prog’s early musicians were formally trained. Others were just highly inspired. The common thread, however, was the influence of non-rock idioms. By contrast, today’s progressive rock bands are mostly influenced only by yesterday’s progressive rock bands. Very few of today’s bands go back to original non-rock sources for their inspiration as the first generation bands did. The worst of today’s bands exist solely in the shadows of their predecessors. Many of today’s prog groups are only influenced by groups that are third- and fourth-generation prog bands themselves. Consider groups like IQ and Iluvatar, who are largely under the influence of early neo-prog bands like Marillion and Pendragon. These two bands are well known for being very derivative of classic-era Genesis, though with a stronger bent toward commercialism. Few of the newer bands like IQ and Iluvatar have ever gone back to the original sources of classical and other non-rock forms that originally influenced Genesis to pen such progressive masterpieces as “Supper’s Ready” and “Firth of Fifth.” Instead they’ve spent their formative years listening to bands like Marillion and Rush, who themselves probably only listened to Genesis and other classic prog bands. Each generation is further removed from the influences that inspired Genesis and the other first-generation bands to greatness. It can easily be observed that each successive generation generally sounds closer to typical rock music than the last, so how truly progressive can the latest bands in this type of family tree be? An extension of this concept lies in the fact that many newer bands are influenced by first-generation bands like Yes or Genesis, but only their more commercial, later material. By the early ‘80s, Yes, Genesis and even many of the lesser-known prog bands had abandoned their earlier, more progressive style in favor of more radio friendly three-and-a-half minute pop songs. While some of this material is engaging in its own way, most of it is not true progressive rock. Yet fans and critics alike often mistakenly continued to call this music progressive rock. It is not uncommon for modern prog bands to cite albums from Yes and Genesis’ top-40 era as major influences. But once again, if these are major influences on groups, who are likely to be even more commercial and less creative than their predecessors, how progressive can these latest bands be? Not very, in this writer’s opinion. Another factor to consider when studying the reasons there are so few high quality progressive rock bands these days is more circumstantial. This is caused by the lack of musicians who are talented or interested enough to play new progressive rock. Since progressive rock has been underground for 25 years, there are obviously very few musicians who are interested in playing progressive rock when there are so many other forms of rock music that are much more commercially viable. Since 1976, fans and musicians alike have turned away from progressive rock to listen to or play other forms of music. By the late 1980s, progressive rock had almost become a lost art. Most kids growing up in this era had never heard of prog, so why or how could they ever want to play it? By the same token, any existing musicians who might have had a desire to play progressive rock at that time would likely have given up due to a lack of interest by music fans as well as the music industry. So, by the late ‘80s, the state of new, original progressive rock could be defined as being caught in a vicious cycle. Nobody was listening, so nobody was playing, so nobody was listening. By the ‘90s, progressive rock had managed to revive itself, due, in part, to the arrival of the internet. People who had been interested in prog all along were now exchanging their opinions on rare albums, sharing concert memories and even trading tapes of their favorite records with each other. Small record companies sprang up to reissue lost classics on CD and mail order companies sprang up to sell them. Inevitably, some of these people were inspired to form new progressive rock bands, but there was still a problem. While a progressive rock enthusiast community had arisen on the internet, proggers were still generally alone in their respective cities and towns. Finding a guitarist who liked Steve Hackett better than Steevie Ray Vaughn – or anyone at all who played keyboards very well – was still a challenge in even the biggest of cities. Even with all of the internet’s ability to connect like-minded people from different parts of the world, it was still pretty difficult for progressive-minded musicians to get together and play, much less record anything. Prog musicians were still relatively isolated when it actually came to getting together and playing or recording. Thus arose what one Exposé magazine reviewer dubbed the “one-man-band syndrome.” This is what happens when one or two dedicated musicians attempt to record a prog album without the help of a full band because they simply can’t find any other musicians willing or talented enough to play with them. The result is often a disappointing, synthetic sounding album, brimming with one person’s musical ideas, but poorly executed and recorded using drum machines and digital “workstation” types of synthesizers – perfect for composing advertising jingles or dance tunes, but downright lame as a substitute for an entire band of virtuoso musicians who might typically have played such diverse instruments as guitar, bass, violin, saxophone, drums and organ. Such “bands” also lack the diverse array of musical influences, backgrounds, personalities and ideas that four or five different individuals might bring to the table in a true band. How can one guy ever come close to creating music on par with a band like Yes, whose various musicians were deeply interested in the widely diverse fields of jazz, rock, classical, country and folk music? There are probably many other factors contributing to the relative inadequacy of much of progressive rock for the last 10 years. I have touched on the ones that I have perceived the most often in my last few years of investigating and writing about new and old progressive rock. Another important factor to consider might be the change in record industry attitudes toward truly forward-thinking music. The experimental atmosphere of the early ‘70s could not be more different from today’s, in which pre-packaged music and public images are designed for only the largest demographic niches of the music buying public. I have also so far neglected to mention that there have been many advancements in progressive rock in the last few years. Many of the newer bands in the Rock in Opposition circle have made remarkable strides in advancing progressive rock’s scope beyond its ‘70s borders. There have been many other bands from around the world that also have breathed new life into classic-styled prog rock within the last decade. Änglagård, Anekdoten, Hoÿry-Kone, Deus Ex Machina, Echolyn and a few others have contributed new entries to the marble halls of prog’s classic albums. This is a relatively small number of bands, however, considering how many new bands have formed in the last decade. The last 10 years have been very good for the state of progressive rock and its enthusiasts. In terms of artistic and commercial success, however, it now seems clear that the prog revival of the 1990s has done relatively little to eclipse progressive rock of the 1970s. Furthermore, it seems the revival is past its peak and now is well into a state of decline. Many of the prog bands of old who regrouped in the 1990s to cash in on prog’s regained popularity seem to have already petered out or have broken up yet again. Most of the really exciting work by ‘90s prog bands seems to have been done early in the decade, and many of those bands have themselves ceased to exist or drastically decreased their output. It seems that the revival has elevated prog rock to a higher plane than it was in the late ‘80s (possibly permanently) but it never again did – and never will – approach the heights of popularity and creativity it did when prog was new.

The editors of Reels of Dreams Unrolled invite and encourage the presentation of contrasting points of view. |

||||

| Genesis: Often imitated, never duplicated. | |||||

|

|||||

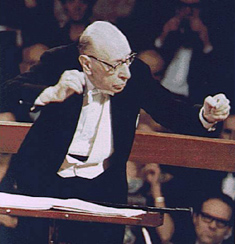

| Heavy metal guitar techniques that many considered obsolete upon the arrival of grunge in the early '90s are still ubiquitous in much of today's "progressive" rock. | |||||

|

|||||

| Many early progressive rock bands were influenced by composers like Igor Stravinsky. | |||||

|

|||||

| Änglagård's first album has been called "a shot heard around the world." The band was a major player in the prog rock revival that began in the early '90s. | |||||