Aircheck Radio Museum

Radio 1 Page 11

Radio 1 Magazine 15th Anniversary Edition

Radio 1 Museum Page 12 AIRCHECK Museum Home Page AIRCHECK home page

And as we continue our stroll through this classic magazine, we feature the double page spread article 'HOW IT ALL BEGAN'... Johnny Beerling writes...

A large number of this magazine's readers won't remember what Radio was like before Radio 1 started. In those days, for all day pop music you could only tune to the illegal pirate stations based off-shore. Back on the land, the BBC had the Light Programme which broadcast a number of pop shows by either live bands with singers or as DJ record shows but they were interspersed with situation comedies, variety shows, or as the name suggests, lots of light music programmes.

When the Government of the day forced the pirates to close down their studios on ships with the Marine Offences Bill, it was up to the BBC to offer a suitable replacement service. In any case, at this time a BBC committee had been examining ways of re-organising broadcasting to provide a more suitable service for the seventies. Their solution was to scrap the old Home, Light and Third Programmes and set up instead Radio 1, 2, 3 and 4 and a chain of local stations, generic radio to give it the proper title, which simply means that each of the four services heard nationally would provide a particular style of entertainment or information for as long as it was on the air.

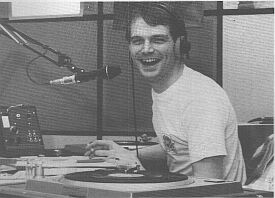

So much for the theory, what did this mean in practice? A minor revolution in Broadcasting House. To start with, the DJs we hired were differently attired from their Light Programme counterparts, and their hair was hardly dressed in the short back and sides worn by the more regular broadcasters. Don't forget this was all happening at the tail end of the Swinging Sixties with psychedelia dictating fashion, and young people everywhere were challenging the accepted conventions.

Many

of the new Radio 1 DJs had learned their craft on the off-shore ships, Kenny

Everett, Tony Blackburn, Stuart

Henry, Duncan Johnson, Emperor Rosko, Dave

Cash, Pete Brady, Mike Lennox, Keith

Skues, Tommy Vance, Chris Denning, Johnny Moran, Ed

Stewart, Mike Ahern and John

Peel, all had come ashore to work for station and if we though John, Rosko

and Stuart were way out in their gear then we were in for another shock when it

came to the actual way they wanted to work.

Many

of the new Radio 1 DJs had learned their craft on the off-shore ships, Kenny

Everett, Tony Blackburn, Stuart

Henry, Duncan Johnson, Emperor Rosko, Dave

Cash, Pete Brady, Mike Lennox, Keith

Skues, Tommy Vance, Chris Denning, Johnny Moran, Ed

Stewart, Mike Ahern and John

Peel, all had come ashore to work for station and if we though John, Rosko

and Stuart were way out in their gear then we were in for another shock when it

came to the actual way they wanted to work.

The producers in the BBC had previously either worked for the Gramophone Department, as I did, where naturally enough, we made programmes using only records, or for the Popular Music Department, based not at Broadcasting House but in New Bond Street in Aeolian Hall. They thought of themselves as the elite of radio because they didn't use records as such but recorded all the music they needed in the BBC's own studios either with Dance Bands playing covers of hits or by re-recording current hits with the top groups of the day. It meant much more work, of course, and the producers took a great pride in trying to get a sounds as close as possible to the original. To some extent we still have to do this to this day because we are limited in the number of hours of music off discs, needle time, that we can play. With the setting up of the new Radio 1 Department, producers from both Popular Music and Gramophone Departments had to work together blending their skills and knowledge to compile the new programmes.

The

equipment too had to change. With more conventional broadcasting of record

programmes, a script was written and copies duplicated before anyone ever went

near a studio. Then, on the day of the transmission, two studio managers

would mix the sound of the DJs voice and play the records whilst a producer

would time everything including the DJ's speech, and following the rehearsal,

cuts would be made to adjust the timing so the duration would be right for the

time slot allocated. The DJ didn't actually handle the records, he sat in

the small studio talking into the microphone looking through the glass at the

producer.

The

equipment too had to change. With more conventional broadcasting of record

programmes, a script was written and copies duplicated before anyone ever went

near a studio. Then, on the day of the transmission, two studio managers

would mix the sound of the DJs voice and play the records whilst a producer

would time everything including the DJ's speech, and following the rehearsal,

cuts would be made to adjust the timing so the duration would be right for the

time slot allocated. The DJ didn't actually handle the records, he sat in

the small studio talking into the microphone looking through the glass at the

producer.

The new breed of DJs hardly ever worked from scripts. They had worked by ad-libbing their way through their shows saying whatever came into their heads, slotting in commercials, news breaks and what records they fancied and adding a freshness and spontaneity which made the pirate stations so attractive to the fans. So the BBC in order to make them feel at home did it's best to accommodate them by converting existing studios to self-operating ones where the DJs could play their own music and jingles.

Jingles too were an addition to the BBC's output. Recorded in America by a company specialising in making such things, they soon set the tone of the new station with their sung announcements telling the listeners that 'Radio 1 was Wonderful!'. It was then, an exciting, if somewhat traumatic time, Auntie giving birth to this lusty young infant, Radio 1. The producers had to learn to cope with the ad-libs of the DJs who bore a considerable responsibility. They had to accept that with a live microphone reaching nearly every household in the country, they couldn't quite say anything that popped into their heads, they had to think before they spoke. The limitations of needle time I wrote of earlier also meant that the DJs couldn't always play what music they like, recorded BBC sessions had to be mixed in with records and great skill was needed by the producers and DJs to see that the joins didn't show too much. A third complication was the lack of money and resources which prevented the complete separation of Radios 1 and 2 - from time to time they came together to present programmes in common.

In

those early days, Tony Blackburn was

exclusive to Radio 1 for the Breakfast Show, but Mid-mornings presented by Jimmy

Young was heard on both Radio 1 and Radio 2, as was the 12 o'clock record

programme 'Midday Spin'. At 1 o'clock we separated and there was generally

a big band show with one of the leading dance bands and guest; Bob Miller and

the Millermen, The Ray McVay Sound, The Northern Dance Orchestra and The Joe

Loss Band all had featured shows. The afternoons and early evenings were

separate with DJs like Pete Brady and Dave Symonds.

In

those early days, Tony Blackburn was

exclusive to Radio 1 for the Breakfast Show, but Mid-mornings presented by Jimmy

Young was heard on both Radio 1 and Radio 2, as was the 12 o'clock record

programme 'Midday Spin'. At 1 o'clock we separated and there was generally

a big band show with one of the leading dance bands and guest; Bob Miller and

the Millermen, The Ray McVay Sound, The Northern Dance Orchestra and The Joe

Loss Band all had featured shows. The afternoons and early evenings were

separate with DJs like Pete Brady and Dave Symonds.

At the weekends, there was a Junior Choice Show, Leslie Crowther was the DJ, and Brian Matthew presented Saturday Club from 1000 - 1200 each week. Emperor Rosko, recorded in Paris where he was one of the biggest DJ names in the World, followed by one hour of non-stop jive talk and music and after him came Jack Jackson. His show was similar to that put together by Adrian Juste today, mixing comedy clips with records.

There were magazine programmes like 'Where It's At' and 'Scene and Heard', and on Sunday mornings Ed Stewart was in charge. Radio 1 and 2 shared output at lunchtimes with 'Family Favourites' before we put on a great rock show 'Top Gear'. Alan Freeman did 'Pick of the Pops' at teatime on Sundays with the Top 20 included before we put on specialist R & B shows for the early evenings.

That's how it started and within those plans can be seen the vague outline of what Radio 1 has developed into today. Of these original DJs, only Tony Blackburn, Tommy Vance and John Peel, with occasional appearances by Rosko, are left, and although the BBC has been in existence for 60 years, Radio 1 has been established for a quarter of that time so we can hardly be regarded as an infant any longer. The child has come of age and with it has developed an increased maturity which hopefully has an even greater appeal for our listeners.

Johnny Beerling.

Don't forget to e-mail us your comments about the site!