VERTIGO'S ACTORS

|

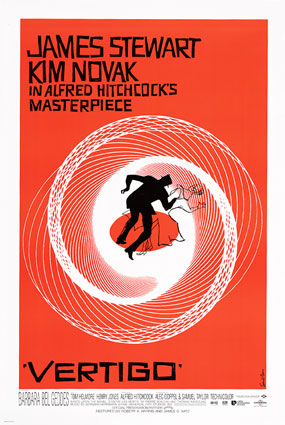

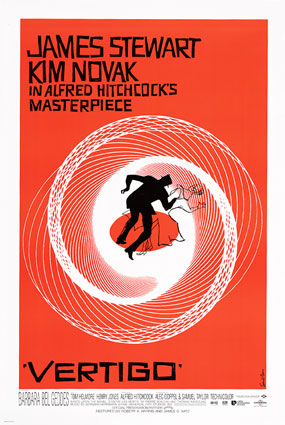

Special on Vertigo (1958)

Special on Vertigo (1958)

Download the Vertigo script here

by Alec Coppel and Samuel W. Taylor

Trailer

“During a rooftop chase, police detective John Scottie Ferguson is overcome with a severe case of acrophobia--a deep fear of falling which results in a stultifying vertigo--that leads to the death of a fellow officer. After retiring from the police force, Scottie attempts to return to a normal life, but his life takes another unusual turn when an old school aquaintance asks Scottie to shadow his wife, the luminescently beautiful but utterly mysterious Madeleine. Scottie is wary but the minute he sees her he cannot resist the chase. As his fixation with Madeleine grows, however, so too does her obsession with death. When Scottie's vertigo prevents him from saving Madeleine's life, his one chance at perfect love comes crashing to a brutal end. Then one day, Scottie sees a woman walking down the street who looks just like Madeleine. She is Judy Barton, a salesgirl from Kansas with her own secrets--secrets that will once again turn Scottie's world into a dizzying battle between illusion and reality.” (by Yahoo Movies).

Reader's comments on IMDB.com

Summary: Hitchcock proves beyond a doubt that he is a master

What can I say. Hitchcock is indeed a master. No wonder everybody studies and imitates him. He can build suspense, make you question at all times what is going on, and keep you on the edge of your seat. This is a great film that any self respecting film buff would have seen by now, and any self respecting movie goer should see. All of the acting is top notch, the visuals, and the pacing of the film is just fantastic. A must see. 10/10

***FOR THOSE WHO HAVE SEEN THE FILM ONLY**** Do you think that this is all a dream that happens in Jimmy Stewart head while he is hanging on the edge of the building at the beginning. If you watch the film, there are just a whole lot of dreamlike elements to the film that just make me question if this is all happening in his head, right down to the very ambiguous ending.

|

Summary: Hitchcock's Crowning Achievement. Watch it!

SPOILERS?!? Jimmy Stewart (John 'Scottie' Ferguson) is hired to follow Kim Novak (Madeleine Elster) around the streets and sights of San Francisco. The twenty or so minutes when this is taking place is almost entirely devoid of dialogue. All we, as an audience, have to do is simply watch their movements around the city. Only Alfred Hitchcock could pull a sequence of this kind off and achieve what he himself referred to as 'pure cinema' - telling a story solely through what we see, not what we hear. It is one of my favourite sections of any movie, let alone Vertigo itself. This section of the film is a masterpiece all by itself.

|

Summary: Hitchcock's greatest and most complex film

An undeniably great film that had all the elements needed to make a classic. I am amazed at how complex the story is. I first saw it about a week ago and was confused, but after repeated viewings I understood it much better. Jimmy Stewart was great as always, but it was Kim Novak's excellent performance as Madeleine Elster/Judy Barton that was surprisingly effective. Bottom Line: If you haven't seen this yet, you're in for a spellbinding, suspenseful, and dark film. Too bad the reviewer below me couldn't see this and bashes it because there is not enough shootouts, explosions,and killings. 10/10

|

Summary: Extraordinary classic suspense from the master!

yaahhhhoo..waaow!unpredictable!suspenseful!brilliant!and...a very hitchcock's best!it was very complex-plot with simply style of hitchcock.it was just the greatest and best movie that i ever watched!kim novak and james stewart were very excellent performances that can created intense and thrilling situation being real!hitchcock still genius and made us..scream,surprise and wiuh!..i have no words again to picture it!

I saw the original last week , watched QUATERMASS 2 yesterday morning and saw the INVASION OF THE BODYSNATCHERS remake last night. I`ve also seen the rather weak 1993 BODYSNATCHERS and the poor PUPPETMASTERS so I think I`m qualified to say this is the best film version dealing with the theme of humans getting taken over.

|

| write a comment |

|

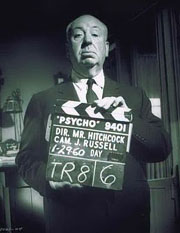

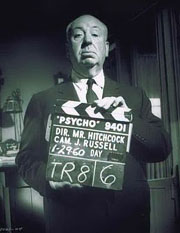

Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock was the most well-known director to the general public, by virtue of both his many thrillers and his appearances on television in his own series from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s. Probably more than any other filmmaker, his name evokes instant expectations on the part of audiences -- they know to expect at least two or three great chills (and a few more good ones), some striking black comedy, and an eccentric characterization or two in every one of the director's movies.

Originally trained at a technical school, Hitchcock gravitated to movies through art courses and advertising, and by the mid-1920s he was making his first films. He had his first major success in 1926 with The Lodger, a thriller loosely based on the career of Jack the Ripper. While he worked in a multitude of genres over the next six years, he found his greatest acceptance working with thrillers. His early work in this genre, including Blackmail (1929) and Murder (1930), seem primitive by modern standards but have many of the essential elements of Hitchcock's subsequent successes, even if they are presented in technically rudimentary terms. Hitchcock came to international attention in the middle and late 1930s with The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), and most notably, The Lady Vanishes (1938). By the end of the 1930s, having gone as far as the British film industry could take him, he signed a contract with David O. Selznick and came to America.

From the outset, with the multi-Oscar winning psychological chiller Rebecca (1940) and the topical anti-Nazi thrillers Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Saboteur (1942), Hitchcock was one of Hollywood's "money" directors whose mere presence on a marquee attracted audiences. Although his relationship with Selznick was stormy, , he created several fine and notable features while working for the producer, either directly for Selznick or on loan to RKO and Universal, including Spellbound (1945), probably the most romantic of Hitchcock's movies; Notorious (1946); and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), considered by many to be his most unsettling film.

In 1948, after leaving Selznick, Hitchcock went through a fallow period, in which he experimented with new techniques and made his first independent production, Rope, but he found little success. In the early and middle 1950s, he returned to form with the thrillers Strangers on a Train (1951), which was remade in 1987 by Danny DeVito as Throw Momma from the Train; Dial M for Murder (1954), which was among the few successful 3-D movies; and Rear Window (1954). By the mid-1950s, Hitchcock's persona became the basis for a television anthology series called Alfred Hitchcock Presents, which ran for eight seasons (although he only directed, or even participated as producer, in a mere handful of the shows). His films of the late 1950s became more personal and daring, particularly The Trouble With Harry (1955) and Vertigo (1958), in which the dark side of romantic obsession was explored in startling detail. Psycho (1960) was Hitchcock's great shock masterpiece, mostly for its haunting performances by Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins and its shower scene, and The Birds (1963) became the unintended forerunner to an onslaught of films about nature-gone-mad, and all were phenomenally popular -- The Birds, in particular, managed to set a new record for its first network television showing in the mid-1960s.

By then, however, Hitchcock's films had slipped seriously at the box office, and understandably so -- both Marnie (1964) and Torn Curtain (1966) suffered from major casting problems, and the script of Torn Curtain was terribly unfocused. He was also hurt by the sudden departure of composer Bernard Herrmann (who had scored all of Hitchcock's movies from 1957 onward) during the making of Torn Curtain, as Herrmann's music had become a key element of the success of Hitchcock's films. Of his final three movies, only Frenzy (1972), which marked his return to British thrillers after 30 years, was successful, although his last film, Family Plot (1976) has achieved some respect from cult audiences. In the early 1980s, several years after his death, Hitchcock's box office appeal was once again displayed with the re-release of Rope, The Trouble With Harry, the 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo, all of which had been withheld from distribution for several years, and which earned millions of dollars in new theatrical revenues. ~ Bruce Eder, All Movie Guide

Kim Novak

Kim Novak was among Hollywood's most enigmatic sex symbols of the '50s and early '60s. Blonde and beautiful, she exuded a daunting intellectual chilliness and an underlying passionate heat that made her especially alluring. One of the last of the studio-made stars, she rebelled against her "manufactured" image, struggling to be seen as more than just another brainless glamour gal. Novak brought to many of her roles a certain melancholic reluctance about freeing up her character's sensuality. It seemed as if her beauty was a burden, not an asset.

She was born Marilyn Pauline Novak and raised in Chicago, the daughter of a Czech railroad man. Before she was discovered in Los Angeles by Columbia Pictures helmer Harry Cohn (who chose her as a replacement for his increasingly difficult and rebellious reigning screen goddess Rita Hayworth), Novak worked odd jobs that included sales clerk, elevator operator, and a spokesmodel for a refrigerator company. Cohn signed her to his studio around 1954. While being properly prepared for stardom, Novak engaged in the first of many battles with Cohn when she refused to allow the studio to bill her as "Kit Marlowe." She felt the name rang false and battled to keep her family name, and then compromised by allowing herself to be called Kim because in her mind, Kit was too close to "kitten," as in the sexy kind. In her later years, Novak would acknowledge the studio head's role in her stardom, but also took plenty of credit for her own hard work.

Though Novak had already made her screen debut with a tiny role in The French Line (1954), her first starring role for Columbia was playing opposite Fred MacMurray in Pushover (1954). At first, she appeared uncomfortable with acting before cameras, but she soon relaxed and the following year had her first big break in Picnic (1955). The film was a hit and Novak found herself the hottest sex symbol in town, a title she wore with discomfort. Unlike other similar stars, Novak was pragmatic and did not lose herself in the glamour of the studio's carefully manufactured blonde bombshell image of her. Despite her dislike of such publicity chores as providing "cheesecake" shots for the press, and going out on studio arranged "dates" to keep her name in print, she was a trooper and toed the company line; some of her alleged lovers from this period include Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, and Aly Khan.

Through the '50s, Novak appeared in a broad range of films of widely varying quality. In 1958, Novak appeared in her most famous role, that of enigmatic Madeleine in Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece Vertigo. It was a difficult role, but one she rose to admirably. She did have one conflict with Hitchcock on the set concerning the stiff gray suit and black shoes she would be required to wear for most of the picture. When she saw costume designer Edith Head's original plans for the suit, Novak, fearing the suit would be distracting and uncomfortable and believing that gray is seldom a blonde's best color, voiced her concerns directly to Hitchcock who listened patiently and then insisted she wear the prescribed garb. Novak obeyed and to her surprise discovered that the starchy outfit enhanced rather than hindered her ability to play Madeleine.

Novak's career continued in high gear through 1965. After appearing in The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders (1965) and marrying her second husband, her film appearances became less frequent. After the loss of her Bel Air home to erosion following a bad fire season in the 1970s, Novak retired and moved to Northern California. There, she and her husband, Dr. Robert Malloy, a veterinarian, raised llamas. She continued to appear on television and in feature films, but only when she wanted to. At home on the ranch she spoke of her screen persona "Kim Novak" as if she were a totally different person. In 1997, she dusted off the old persona to go on an extensive promotional tour to alert the public to the fully restored version of Vertigo. When not busy in Hollywood, Novak continues working on her autobiography. ~ Sandra Brennan, All Movie Guide

James Stewart

James Stewart was the movies' quintessential Everyman, a uniquely all-American performer who parlayed his easygoing persona into one of the most successful and enduring careers in film history. On paper, he was anything but the typical Hollywood star: Gawky and tentative, with a pronounced stammer and a folksy "aw-shucks" charm, he lacked the dashing sophistication and swashbuckling heroism endemic among the other major actors of the era. Yet it's precisely the absence of affectation which made Stewart so popular; while so many other great stars seemed remote and larger than life, he never lost touch with his humanity, projecting an uncommon sense of goodness and decency which made him immensely likable and endearing to successive generations of moviegoers.

Born May 20, 1908, in Indiana, PA, Stewart began performing magic as a child. While studying civil engineering at Princeton University, he befriended Joshua Logan, who then headed a summer stock company, and appeared in several of his productions. After graduation, Stewart joined Logan's University Players, a troupe whose membership also included Henry Fonda and Margaret Sullavan. He and Fonda traveled to New York City in 1932, where they began winning small roles in Broadway productions including Carrie Nation, Yellow Jack, and Page Miss Glory. On the recommendation of Hedda Hopper, MGM scheduled a screen test, and soon Stewart was signed to a long-term contract. He first appeared onscreen in a bit role in the 1935 Spencer Tracy vehicle The Murder Man, followed by another small performance the next year in Rose Marie.

Stewart's first prominent role came courtesy of Sullavan, who requested he play her husband in the 1936 melodrama Next Time We Love. Speed, one of six other films he made that same year, was his first lead role. His next major performance cast him as Eleanor Powell's paramour in the musical Born to Dance, after which he accepted a supporting turn in After the Thin Man. For 1938's classic You Can't Take It With You, Stewart teamed for the first time with Frank Capra, the director who guided him during many of his most memorable performances. They reunited a year later for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stewart's breakthrough picture; a hugely popular modern morality play set against the backdrop of the Washington political system, it cemented the all-American persona which made him so adored by fans, earning a New York Film Critics' Best Actor award as well as his first Oscar nomination.

Stewart then embarked on a string of commercial and critical successes which elevated him to the status of superstar; the first was the idiosyncratic 1939 Western Destry Rides Again, followed by the 1940 Ernst Lubitsch romantic comedy The Shop Around the Corner. After The Mortal Storm, he starred opposite Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant in George Cukor's sublime The Philadelphia Story, a performance which earned him the Best Actor Oscar. However, Stewart soon entered duty in World War II, serving as a bomber pilot and flying 20 missions over Germany. He was highly decorated for his courage, and did not fully retire from the service until 1968, by which time he was an Air Force Brigadier General, the highest-ranking entertainer in the U.S. military.

Stewart's combat experiences left him a changed man; where during the prewar era he often played shy, tentative characters, he returned to films with a new intensity. While remaining as genial and likable as ever, he began to explore new, more complex facets of his acting abilities, accepting roles in darker and more thought-provoking films. The first was Capra's 1946 perennial It's a Wonderful Life, which cast Stewart as a suicidal banker who learns the true value of life. Through years of TV reruns, the film became a staple of Christmastime viewing, and remains arguably Stewart's best-known and most-beloved performance. However, it was not a hit upon its original theatrical release, nor was the follow-up Magic Town -- audiences clearly wanted the escapist fare of Hollywood's prewar era, not the more pensive material so many other actors and filmmakers as well as Stewart wanted to explore in the wake of battle.

The 1948 thriller Call Northside 777 was a concession to audience demands, and fans responded by making the film a considerable hit. Regardless, Stewart next teamed for the first time with Alfred Hitchcock in Rope, accepting a supporting role in a tale based on the infamous Leopold and Loeb murder case. His next few pictures failed to generate much notice, but in 1950, Stewart starred in a pair of Westerns, Anthony Mann's Winchester 73 and Delmer Daves' Broken Arrow. Both were hugely successful, and after completing an Oscar-nominated turn as a drunk in the comedy Harvey and appearing in Cecil B. De Mille's Academy Award-winning The Greatest Show on Earth, he made another Western, 1952's Bend of the River, the first in a decade of many similar genre pieces.

Stewart spent the 1950s primarily in the employ of Universal, cutting one of the first percentage-basis contracts in Hollywood -- a major breakthrough soon to be followed by virtually every other motion-picture star. He often worked with director Mann, who guided him to hits including The Naked Spur, Thunder Bay, The Man From Laramie, and The Far Country. For Hitchcock, Stewart starred in 1954's masterful Rear Window, appearing against type as a crippled photographer obsessively peeking in on the lives of his neighbors. More than perhaps any other director, Hitchcock challenged the very assumptions of the Stewart persona by casting him in roles which questioned his character's morality, even his sanity. They reunited twice more, in 1956's The Man Who Knew Too Much and 1958's brilliant Vertigo, and together both director and star rose to the occasion by delivering some of the best work of their respective careers.

Apart from Mann and Hitchcock, Stewart also worked with the likes of Billy Wilder (1957's Charles Lindbergh biopic The Spirit of St. Louis) and Otto Preminger (1959's provocative courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, which earned him yet another Best Actor bid). Under John Ford, Stewart starred in 1961's Two Rode Together and the following year's excellent The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The 1962 comedy Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation was also a hit, and Stewart spent the remainder of the decade alternating between Westerns and family comedies. By the early '70s, he announced his semi-retirement from movies, but still occasionally resurfaced in pictures like the 1976 John Wayne vehicle The Shootist and 1978's The Big Sleep. By the 1980s, Stewart's acting had become even more limited, and he spent much of his final years writing poetry; he died July 2, 1997. ~ Jason Ankeny, All Movie Guide

Bernard Herrmann

A composition prize winner at age 13, Manhattan-born composer Bernard Herrmann studied at New York University and Julliard before accepting his first conductor's post at age 20. While he wrote for virtually every branch of the musical theater -- ballet, concert hall, opera -- Herrmann's latter-day fame rests squarely on his prolific film work. As one of several composer/conductors retained by the CBS radio network in the mid-1930s (he was briefly married to radio writer Lucille Fletcher, of Sorry Wrong Number fame), Herrmann worked on Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre of the Air. When Welles headed to Hollywood to direct Citizen Kane (1941), he invited Herrmann to write the film's score, promising the young composer full artistic freedom. Welles so respected Herrmann's talent that many scenes in Kane were tailored to fit the music, rather than the other way around. Herrmann capped his first year in Hollywood with an Academy Award -- not for Kane, but for another RKO production, All That Money Can Buy (1941). He was engaged to score Welles' second picture, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), but angrily demanded that his name be removed from the credits after his music was extensively rearranged by RKO contractee Roy Webb. The range of Herrmann's talent was so enormous that he remained in demand until his death in 1975. With Jane Eyre (1944), Herrmann began a lengthy association with 20th Century-Fox, best exemplified by the scores for such films as The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), Five Fingers (1952), The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1953) and The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1954). At his best, Herrmann was tirelessly creative, ever finding new ways to match his scores to the mood and locale of his films. As one of many examples, Herrmann wrote an orchestration incorporating authentic native African musical instruments for the 1954 jungle actioner White Witch Doctor. Many of his innovations have since become cinematic clichés, notably his vibraphonic score for the 1951 sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still and the screeching violins for 1960's Psycho. In the 1950s, Herrmann inaugurated two long associations with a brace of notable filmmakers: special-effects maven Ray Harryhausen (Seventh Voyage of Sinbad [1957], Mysterious Island [1961], Three Worlds of Gulliver [1962], Jason and the Argonauts [1963]) and suspense specialist Alfred Hitchcock (The Trouble With Harry [1955], The Wrong Man [1956], Vertigo [1958], North by Northwest [1959], Psycho [1960], Marnie [1964] and The Birds [1963], for which Herrmann orchestrated genuine bird sounds). After acrimoniously severing his ties with Hitchcock over a dispute arising from the score of 1966's Torn Curtain, Herrmann accepted assignments from a number of Hitchcock emulators, including Francois Truffaut (The Bride Wore Black [1967]), Larry Cohen (It's Alive! [1974]) and Brian De Palma (Obsession [1976]). Herrmann also kept busy on TV, principally on Rod Serling's Twilight Zone series; for the 1962 Zone episode "Little Girl Lost," the composer was billed above the director. Herrmann's final score was for Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1975), which was posthumously dedicated to Herrmann. ~ Hal Erickson, All Movie Guide

Pierre Boileau

Pierre Boileau and his partner Thomas Narcejac wrote numerous best-selling suspense novels, many of which were adapted into films. Among these adaptations are Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958) and Clouzot's Diabolique (1955). They also adapted other author's books for screen and wrote a few original screenplays of their own. ~ Sandra Brennan, All Movie Guide

top

|

|

Special on Vertigo (1958)

Special on Vertigo (1958) Alfred Hitchcock was the most well-known director to the general public, by virtue of both his many thrillers and his appearances on television in his own series from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s. Probably more than any other filmmaker, his name evokes instant expectations on the part of audiences -- they know to expect at least two or three great chills (and a few more good ones), some striking black comedy, and an eccentric characterization or two in every one of the director's movies.

Originally trained at a technical school, Hitchcock gravitated to movies through art courses and advertising, and by the mid-1920s he was making his first films. He had his first major success in 1926 with The Lodger, a thriller loosely based on the career of Jack the Ripper. While he worked in a multitude of genres over the next six years, he found his greatest acceptance working with thrillers. His early work in this genre, including Blackmail (1929) and Murder (1930), seem primitive by modern standards but have many of the essential elements of Hitchcock's subsequent successes, even if they are presented in technically rudimentary terms. Hitchcock came to international attention in the middle and late 1930s with The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), and most notably, The Lady Vanishes (1938). By the end of the 1930s, having gone as far as the British film industry could take him, he signed a contract with David O. Selznick and came to America.

From the outset, with the multi-Oscar winning psychological chiller Rebecca (1940) and the topical anti-Nazi thrillers Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Saboteur (1942), Hitchcock was one of Hollywood's "money" directors whose mere presence on a marquee attracted audiences. Although his relationship with Selznick was stormy, , he created several fine and notable features while working for the producer, either directly for Selznick or on loan to RKO and Universal, including Spellbound (1945), probably the most romantic of Hitchcock's movies; Notorious (1946); and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), considered by many to be his most unsettling film.

In 1948, after leaving Selznick, Hitchcock went through a fallow period, in which he experimented with new techniques and made his first independent production, Rope, but he found little success. In the early and middle 1950s, he returned to form with the thrillers Strangers on a Train (1951), which was remade in 1987 by Danny DeVito as Throw Momma from the Train; Dial M for Murder (1954), which was among the few successful 3-D movies; and Rear Window (1954). By the mid-1950s, Hitchcock's persona became the basis for a television anthology series called Alfred Hitchcock Presents, which ran for eight seasons (although he only directed, or even participated as producer, in a mere handful of the shows). His films of the late 1950s became more personal and daring, particularly The Trouble With Harry (1955) and Vertigo (1958), in which the dark side of romantic obsession was explored in startling detail. Psycho (1960) was Hitchcock's great shock masterpiece, mostly for its haunting performances by Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins and its shower scene, and The Birds (1963) became the unintended forerunner to an onslaught of films about nature-gone-mad, and all were phenomenally popular -- The Birds, in particular, managed to set a new record for its first network television showing in the mid-1960s.

By then, however, Hitchcock's films had slipped seriously at the box office, and understandably so -- both Marnie (1964) and Torn Curtain (1966) suffered from major casting problems, and the script of Torn Curtain was terribly unfocused. He was also hurt by the sudden departure of composer Bernard Herrmann (who had scored all of Hitchcock's movies from 1957 onward) during the making of Torn Curtain, as Herrmann's music had become a key element of the success of Hitchcock's films. Of his final three movies, only Frenzy (1972), which marked his return to British thrillers after 30 years, was successful, although his last film, Family Plot (1976) has achieved some respect from cult audiences. In the early 1980s, several years after his death, Hitchcock's box office appeal was once again displayed with the re-release of Rope, The Trouble With Harry, the 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo, all of which had been withheld from distribution for several years, and which earned millions of dollars in new theatrical revenues. ~ Bruce Eder, All Movie Guide

Alfred Hitchcock was the most well-known director to the general public, by virtue of both his many thrillers and his appearances on television in his own series from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s. Probably more than any other filmmaker, his name evokes instant expectations on the part of audiences -- they know to expect at least two or three great chills (and a few more good ones), some striking black comedy, and an eccentric characterization or two in every one of the director's movies.

Originally trained at a technical school, Hitchcock gravitated to movies through art courses and advertising, and by the mid-1920s he was making his first films. He had his first major success in 1926 with The Lodger, a thriller loosely based on the career of Jack the Ripper. While he worked in a multitude of genres over the next six years, he found his greatest acceptance working with thrillers. His early work in this genre, including Blackmail (1929) and Murder (1930), seem primitive by modern standards but have many of the essential elements of Hitchcock's subsequent successes, even if they are presented in technically rudimentary terms. Hitchcock came to international attention in the middle and late 1930s with The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), and most notably, The Lady Vanishes (1938). By the end of the 1930s, having gone as far as the British film industry could take him, he signed a contract with David O. Selznick and came to America.

From the outset, with the multi-Oscar winning psychological chiller Rebecca (1940) and the topical anti-Nazi thrillers Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Saboteur (1942), Hitchcock was one of Hollywood's "money" directors whose mere presence on a marquee attracted audiences. Although his relationship with Selznick was stormy, , he created several fine and notable features while working for the producer, either directly for Selznick or on loan to RKO and Universal, including Spellbound (1945), probably the most romantic of Hitchcock's movies; Notorious (1946); and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), considered by many to be his most unsettling film.

In 1948, after leaving Selznick, Hitchcock went through a fallow period, in which he experimented with new techniques and made his first independent production, Rope, but he found little success. In the early and middle 1950s, he returned to form with the thrillers Strangers on a Train (1951), which was remade in 1987 by Danny DeVito as Throw Momma from the Train; Dial M for Murder (1954), which was among the few successful 3-D movies; and Rear Window (1954). By the mid-1950s, Hitchcock's persona became the basis for a television anthology series called Alfred Hitchcock Presents, which ran for eight seasons (although he only directed, or even participated as producer, in a mere handful of the shows). His films of the late 1950s became more personal and daring, particularly The Trouble With Harry (1955) and Vertigo (1958), in which the dark side of romantic obsession was explored in startling detail. Psycho (1960) was Hitchcock's great shock masterpiece, mostly for its haunting performances by Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins and its shower scene, and The Birds (1963) became the unintended forerunner to an onslaught of films about nature-gone-mad, and all were phenomenally popular -- The Birds, in particular, managed to set a new record for its first network television showing in the mid-1960s.

By then, however, Hitchcock's films had slipped seriously at the box office, and understandably so -- both Marnie (1964) and Torn Curtain (1966) suffered from major casting problems, and the script of Torn Curtain was terribly unfocused. He was also hurt by the sudden departure of composer Bernard Herrmann (who had scored all of Hitchcock's movies from 1957 onward) during the making of Torn Curtain, as Herrmann's music had become a key element of the success of Hitchcock's films. Of his final three movies, only Frenzy (1972), which marked his return to British thrillers after 30 years, was successful, although his last film, Family Plot (1976) has achieved some respect from cult audiences. In the early 1980s, several years after his death, Hitchcock's box office appeal was once again displayed with the re-release of Rope, The Trouble With Harry, the 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo, all of which had been withheld from distribution for several years, and which earned millions of dollars in new theatrical revenues. ~ Bruce Eder, All Movie Guide

Kim Novak was among Hollywood's most enigmatic sex symbols of the '50s and early '60s. Blonde and beautiful, she exuded a daunting intellectual chilliness and an underlying passionate heat that made her especially alluring. One of the last of the studio-made stars, she rebelled against her "manufactured" image, struggling to be seen as more than just another brainless glamour gal. Novak brought to many of her roles a certain melancholic reluctance about freeing up her character's sensuality. It seemed as if her beauty was a burden, not an asset.

She was born Marilyn Pauline Novak and raised in Chicago, the daughter of a Czech railroad man. Before she was discovered in Los Angeles by Columbia Pictures helmer Harry Cohn (who chose her as a replacement for his increasingly difficult and rebellious reigning screen goddess Rita Hayworth), Novak worked odd jobs that included sales clerk, elevator operator, and a spokesmodel for a refrigerator company. Cohn signed her to his studio around 1954. While being properly prepared for stardom, Novak engaged in the first of many battles with Cohn when she refused to allow the studio to bill her as "Kit Marlowe." She felt the name rang false and battled to keep her family name, and then compromised by allowing herself to be called Kim because in her mind, Kit was too close to "kitten," as in the sexy kind. In her later years, Novak would acknowledge the studio head's role in her stardom, but also took plenty of credit for her own hard work.

Though Novak had already made her screen debut with a tiny role in The French Line (1954), her first starring role for Columbia was playing opposite Fred MacMurray in Pushover (1954). At first, she appeared uncomfortable with acting before cameras, but she soon relaxed and the following year had her first big break in Picnic (1955). The film was a hit and Novak found herself the hottest sex symbol in town, a title she wore with discomfort. Unlike other similar stars, Novak was pragmatic and did not lose herself in the glamour of the studio's carefully manufactured blonde bombshell image of her. Despite her dislike of such publicity chores as providing "cheesecake" shots for the press, and going out on studio arranged "dates" to keep her name in print, she was a trooper and toed the company line; some of her alleged lovers from this period include Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, and Aly Khan.

Through the '50s, Novak appeared in a broad range of films of widely varying quality. In 1958, Novak appeared in her most famous role, that of enigmatic Madeleine in Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece Vertigo. It was a difficult role, but one she rose to admirably. She did have one conflict with Hitchcock on the set concerning the stiff gray suit and black shoes she would be required to wear for most of the picture. When she saw costume designer Edith Head's original plans for the suit, Novak, fearing the suit would be distracting and uncomfortable and believing that gray is seldom a blonde's best color, voiced her concerns directly to Hitchcock who listened patiently and then insisted she wear the prescribed garb. Novak obeyed and to her surprise discovered that the starchy outfit enhanced rather than hindered her ability to play Madeleine.

Novak's career continued in high gear through 1965. After appearing in The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders (1965) and marrying her second husband, her film appearances became less frequent. After the loss of her Bel Air home to erosion following a bad fire season in the 1970s, Novak retired and moved to Northern California. There, she and her husband, Dr. Robert Malloy, a veterinarian, raised llamas. She continued to appear on television and in feature films, but only when she wanted to. At home on the ranch she spoke of her screen persona "Kim Novak" as if she were a totally different person. In 1997, she dusted off the old persona to go on an extensive promotional tour to alert the public to the fully restored version of Vertigo. When not busy in Hollywood, Novak continues working on her autobiography. ~ Sandra Brennan, All Movie Guide

Kim Novak was among Hollywood's most enigmatic sex symbols of the '50s and early '60s. Blonde and beautiful, she exuded a daunting intellectual chilliness and an underlying passionate heat that made her especially alluring. One of the last of the studio-made stars, she rebelled against her "manufactured" image, struggling to be seen as more than just another brainless glamour gal. Novak brought to many of her roles a certain melancholic reluctance about freeing up her character's sensuality. It seemed as if her beauty was a burden, not an asset.

She was born Marilyn Pauline Novak and raised in Chicago, the daughter of a Czech railroad man. Before she was discovered in Los Angeles by Columbia Pictures helmer Harry Cohn (who chose her as a replacement for his increasingly difficult and rebellious reigning screen goddess Rita Hayworth), Novak worked odd jobs that included sales clerk, elevator operator, and a spokesmodel for a refrigerator company. Cohn signed her to his studio around 1954. While being properly prepared for stardom, Novak engaged in the first of many battles with Cohn when she refused to allow the studio to bill her as "Kit Marlowe." She felt the name rang false and battled to keep her family name, and then compromised by allowing herself to be called Kim because in her mind, Kit was too close to "kitten," as in the sexy kind. In her later years, Novak would acknowledge the studio head's role in her stardom, but also took plenty of credit for her own hard work.

Though Novak had already made her screen debut with a tiny role in The French Line (1954), her first starring role for Columbia was playing opposite Fred MacMurray in Pushover (1954). At first, she appeared uncomfortable with acting before cameras, but she soon relaxed and the following year had her first big break in Picnic (1955). The film was a hit and Novak found herself the hottest sex symbol in town, a title she wore with discomfort. Unlike other similar stars, Novak was pragmatic and did not lose herself in the glamour of the studio's carefully manufactured blonde bombshell image of her. Despite her dislike of such publicity chores as providing "cheesecake" shots for the press, and going out on studio arranged "dates" to keep her name in print, she was a trooper and toed the company line; some of her alleged lovers from this period include Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, and Aly Khan.

Through the '50s, Novak appeared in a broad range of films of widely varying quality. In 1958, Novak appeared in her most famous role, that of enigmatic Madeleine in Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece Vertigo. It was a difficult role, but one she rose to admirably. She did have one conflict with Hitchcock on the set concerning the stiff gray suit and black shoes she would be required to wear for most of the picture. When she saw costume designer Edith Head's original plans for the suit, Novak, fearing the suit would be distracting and uncomfortable and believing that gray is seldom a blonde's best color, voiced her concerns directly to Hitchcock who listened patiently and then insisted she wear the prescribed garb. Novak obeyed and to her surprise discovered that the starchy outfit enhanced rather than hindered her ability to play Madeleine.

Novak's career continued in high gear through 1965. After appearing in The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders (1965) and marrying her second husband, her film appearances became less frequent. After the loss of her Bel Air home to erosion following a bad fire season in the 1970s, Novak retired and moved to Northern California. There, she and her husband, Dr. Robert Malloy, a veterinarian, raised llamas. She continued to appear on television and in feature films, but only when she wanted to. At home on the ranch she spoke of her screen persona "Kim Novak" as if she were a totally different person. In 1997, she dusted off the old persona to go on an extensive promotional tour to alert the public to the fully restored version of Vertigo. When not busy in Hollywood, Novak continues working on her autobiography. ~ Sandra Brennan, All Movie Guide

James Stewart was the movies' quintessential Everyman, a uniquely all-American performer who parlayed his easygoing persona into one of the most successful and enduring careers in film history. On paper, he was anything but the typical Hollywood star: Gawky and tentative, with a pronounced stammer and a folksy "aw-shucks" charm, he lacked the dashing sophistication and swashbuckling heroism endemic among the other major actors of the era. Yet it's precisely the absence of affectation which made Stewart so popular; while so many other great stars seemed remote and larger than life, he never lost touch with his humanity, projecting an uncommon sense of goodness and decency which made him immensely likable and endearing to successive generations of moviegoers.

Born May 20, 1908, in Indiana, PA, Stewart began performing magic as a child. While studying civil engineering at Princeton University, he befriended Joshua Logan, who then headed a summer stock company, and appeared in several of his productions. After graduation, Stewart joined Logan's University Players, a troupe whose membership also included Henry Fonda and Margaret Sullavan. He and Fonda traveled to New York City in 1932, where they began winning small roles in Broadway productions including Carrie Nation, Yellow Jack, and Page Miss Glory. On the recommendation of Hedda Hopper, MGM scheduled a screen test, and soon Stewart was signed to a long-term contract. He first appeared onscreen in a bit role in the 1935 Spencer Tracy vehicle The Murder Man, followed by another small performance the next year in Rose Marie.

Stewart's first prominent role came courtesy of Sullavan, who requested he play her husband in the 1936 melodrama Next Time We Love. Speed, one of six other films he made that same year, was his first lead role. His next major performance cast him as Eleanor Powell's paramour in the musical Born to Dance, after which he accepted a supporting turn in After the Thin Man. For 1938's classic You Can't Take It With You, Stewart teamed for the first time with Frank Capra, the director who guided him during many of his most memorable performances. They reunited a year later for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stewart's breakthrough picture; a hugely popular modern morality play set against the backdrop of the Washington political system, it cemented the all-American persona which made him so adored by fans, earning a New York Film Critics' Best Actor award as well as his first Oscar nomination.

Stewart then embarked on a string of commercial and critical successes which elevated him to the status of superstar; the first was the idiosyncratic 1939 Western Destry Rides Again, followed by the 1940 Ernst Lubitsch romantic comedy The Shop Around the Corner. After The Mortal Storm, he starred opposite Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant in George Cukor's sublime The Philadelphia Story, a performance which earned him the Best Actor Oscar. However, Stewart soon entered duty in World War II, serving as a bomber pilot and flying 20 missions over Germany. He was highly decorated for his courage, and did not fully retire from the service until 1968, by which time he was an Air Force Brigadier General, the highest-ranking entertainer in the U.S. military.

Stewart's combat experiences left him a changed man; where during the prewar era he often played shy, tentative characters, he returned to films with a new intensity. While remaining as genial and likable as ever, he began to explore new, more complex facets of his acting abilities, accepting roles in darker and more thought-provoking films. The first was Capra's 1946 perennial It's a Wonderful Life, which cast Stewart as a suicidal banker who learns the true value of life. Through years of TV reruns, the film became a staple of Christmastime viewing, and remains arguably Stewart's best-known and most-beloved performance. However, it was not a hit upon its original theatrical release, nor was the follow-up Magic Town -- audiences clearly wanted the escapist fare of Hollywood's prewar era, not the more pensive material so many other actors and filmmakers as well as Stewart wanted to explore in the wake of battle.

The 1948 thriller Call Northside 777 was a concession to audience demands, and fans responded by making the film a considerable hit. Regardless, Stewart next teamed for the first time with Alfred Hitchcock in Rope, accepting a supporting role in a tale based on the infamous Leopold and Loeb murder case. His next few pictures failed to generate much notice, but in 1950, Stewart starred in a pair of Westerns, Anthony Mann's Winchester 73 and Delmer Daves' Broken Arrow. Both were hugely successful, and after completing an Oscar-nominated turn as a drunk in the comedy Harvey and appearing in Cecil B. De Mille's Academy Award-winning The Greatest Show on Earth, he made another Western, 1952's Bend of the River, the first in a decade of many similar genre pieces.

Stewart spent the 1950s primarily in the employ of Universal, cutting one of the first percentage-basis contracts in Hollywood -- a major breakthrough soon to be followed by virtually every other motion-picture star. He often worked with director Mann, who guided him to hits including The Naked Spur, Thunder Bay, The Man From Laramie, and The Far Country. For Hitchcock, Stewart starred in 1954's masterful Rear Window, appearing against type as a crippled photographer obsessively peeking in on the lives of his neighbors. More than perhaps any other director, Hitchcock challenged the very assumptions of the Stewart persona by casting him in roles which questioned his character's morality, even his sanity. They reunited twice more, in 1956's The Man Who Knew Too Much and 1958's brilliant Vertigo, and together both director and star rose to the occasion by delivering some of the best work of their respective careers.

Apart from Mann and Hitchcock, Stewart also worked with the likes of Billy Wilder (1957's Charles Lindbergh biopic The Spirit of St. Louis) and Otto Preminger (1959's provocative courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, which earned him yet another Best Actor bid). Under John Ford, Stewart starred in 1961's Two Rode Together and the following year's excellent The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The 1962 comedy Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation was also a hit, and Stewart spent the remainder of the decade alternating between Westerns and family comedies. By the early '70s, he announced his semi-retirement from movies, but still occasionally resurfaced in pictures like the 1976 John Wayne vehicle The Shootist and 1978's The Big Sleep. By the 1980s, Stewart's acting had become even more limited, and he spent much of his final years writing poetry; he died July 2, 1997. ~ Jason Ankeny, All Movie Guide

James Stewart was the movies' quintessential Everyman, a uniquely all-American performer who parlayed his easygoing persona into one of the most successful and enduring careers in film history. On paper, he was anything but the typical Hollywood star: Gawky and tentative, with a pronounced stammer and a folksy "aw-shucks" charm, he lacked the dashing sophistication and swashbuckling heroism endemic among the other major actors of the era. Yet it's precisely the absence of affectation which made Stewart so popular; while so many other great stars seemed remote and larger than life, he never lost touch with his humanity, projecting an uncommon sense of goodness and decency which made him immensely likable and endearing to successive generations of moviegoers.

Born May 20, 1908, in Indiana, PA, Stewart began performing magic as a child. While studying civil engineering at Princeton University, he befriended Joshua Logan, who then headed a summer stock company, and appeared in several of his productions. After graduation, Stewart joined Logan's University Players, a troupe whose membership also included Henry Fonda and Margaret Sullavan. He and Fonda traveled to New York City in 1932, where they began winning small roles in Broadway productions including Carrie Nation, Yellow Jack, and Page Miss Glory. On the recommendation of Hedda Hopper, MGM scheduled a screen test, and soon Stewart was signed to a long-term contract. He first appeared onscreen in a bit role in the 1935 Spencer Tracy vehicle The Murder Man, followed by another small performance the next year in Rose Marie.

Stewart's first prominent role came courtesy of Sullavan, who requested he play her husband in the 1936 melodrama Next Time We Love. Speed, one of six other films he made that same year, was his first lead role. His next major performance cast him as Eleanor Powell's paramour in the musical Born to Dance, after which he accepted a supporting turn in After the Thin Man. For 1938's classic You Can't Take It With You, Stewart teamed for the first time with Frank Capra, the director who guided him during many of his most memorable performances. They reunited a year later for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stewart's breakthrough picture; a hugely popular modern morality play set against the backdrop of the Washington political system, it cemented the all-American persona which made him so adored by fans, earning a New York Film Critics' Best Actor award as well as his first Oscar nomination.

Stewart then embarked on a string of commercial and critical successes which elevated him to the status of superstar; the first was the idiosyncratic 1939 Western Destry Rides Again, followed by the 1940 Ernst Lubitsch romantic comedy The Shop Around the Corner. After The Mortal Storm, he starred opposite Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant in George Cukor's sublime The Philadelphia Story, a performance which earned him the Best Actor Oscar. However, Stewart soon entered duty in World War II, serving as a bomber pilot and flying 20 missions over Germany. He was highly decorated for his courage, and did not fully retire from the service until 1968, by which time he was an Air Force Brigadier General, the highest-ranking entertainer in the U.S. military.

Stewart's combat experiences left him a changed man; where during the prewar era he often played shy, tentative characters, he returned to films with a new intensity. While remaining as genial and likable as ever, he began to explore new, more complex facets of his acting abilities, accepting roles in darker and more thought-provoking films. The first was Capra's 1946 perennial It's a Wonderful Life, which cast Stewart as a suicidal banker who learns the true value of life. Through years of TV reruns, the film became a staple of Christmastime viewing, and remains arguably Stewart's best-known and most-beloved performance. However, it was not a hit upon its original theatrical release, nor was the follow-up Magic Town -- audiences clearly wanted the escapist fare of Hollywood's prewar era, not the more pensive material so many other actors and filmmakers as well as Stewart wanted to explore in the wake of battle.

The 1948 thriller Call Northside 777 was a concession to audience demands, and fans responded by making the film a considerable hit. Regardless, Stewart next teamed for the first time with Alfred Hitchcock in Rope, accepting a supporting role in a tale based on the infamous Leopold and Loeb murder case. His next few pictures failed to generate much notice, but in 1950, Stewart starred in a pair of Westerns, Anthony Mann's Winchester 73 and Delmer Daves' Broken Arrow. Both were hugely successful, and after completing an Oscar-nominated turn as a drunk in the comedy Harvey and appearing in Cecil B. De Mille's Academy Award-winning The Greatest Show on Earth, he made another Western, 1952's Bend of the River, the first in a decade of many similar genre pieces.

Stewart spent the 1950s primarily in the employ of Universal, cutting one of the first percentage-basis contracts in Hollywood -- a major breakthrough soon to be followed by virtually every other motion-picture star. He often worked with director Mann, who guided him to hits including The Naked Spur, Thunder Bay, The Man From Laramie, and The Far Country. For Hitchcock, Stewart starred in 1954's masterful Rear Window, appearing against type as a crippled photographer obsessively peeking in on the lives of his neighbors. More than perhaps any other director, Hitchcock challenged the very assumptions of the Stewart persona by casting him in roles which questioned his character's morality, even his sanity. They reunited twice more, in 1956's The Man Who Knew Too Much and 1958's brilliant Vertigo, and together both director and star rose to the occasion by delivering some of the best work of their respective careers.

Apart from Mann and Hitchcock, Stewart also worked with the likes of Billy Wilder (1957's Charles Lindbergh biopic The Spirit of St. Louis) and Otto Preminger (1959's provocative courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, which earned him yet another Best Actor bid). Under John Ford, Stewart starred in 1961's Two Rode Together and the following year's excellent The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The 1962 comedy Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation was also a hit, and Stewart spent the remainder of the decade alternating between Westerns and family comedies. By the early '70s, he announced his semi-retirement from movies, but still occasionally resurfaced in pictures like the 1976 John Wayne vehicle The Shootist and 1978's The Big Sleep. By the 1980s, Stewart's acting had become even more limited, and he spent much of his final years writing poetry; he died July 2, 1997. ~ Jason Ankeny, All Movie Guide