About Fencing: Fencing for Beginners, September 2003

Welcome to the University of Calgary Fencing Club! This is just a little introduction to some basic concepts and terms used in the sport. The sections on Equipment, Safety, The Foil, Priority, and The Bout are considered required reading. The rest is optional, but recommended to give you a better overall understanding of the sport. For more information about the sport, further reading, pictures, and other fun stuff, check out the club’s website: www.oocities.org/uofcfencing.

Before We Begin

Fencing is a sport with a centuries-long history. Its practice has always been founded on knowledge, discipline, and honour. Fencing therefore demands a sense of sincerity and respect, and a desire to learn and improve. We hope you will keep this in mind while you fence. A complete list of Club Rules and Etiquette is posted inside the mask cabinet door.

Equipment

The basic pieces of fencing equipment are:

- Weapons: Modern fencing involves three weapons, the foil, the sabre, and the épée. Each weapon employs slightly different rules and techniques. In a bout, both fencers use the same type of weapon. At tournaments, all three weapons are scored electrically. The weapons are available in left- or right-handed configurations. Your safety and the safety of others depend on the proper maintenance and treatment of these weapons. Respect the weapon, and always remember when you’re fencing, the trick is finesse, not force.

- Mask: The mask protects the face and head. It should fit comfortably and you should be able to talk while wearing it. If it rattles when you shake your head, it is too loose. The sides of the mask should completely cover your ears. Avoid dropping masks, as this may weaken the mesh and endanger the wearer.

- Jacket: The fencing jacket must cover the entire foil target area and the arms. The cloth must be thick cotton or similar material, and must be white. The jacket should fit snugly but not restrict movement. Some jackets are left- or right-hand specific. The zipper should either be in back, or on the side of your chest opposite your weapon hand. Women’s jackets have pockets sewn inside of the front to hold the chest protectors. Hang jackets up after use to allow them to dry. Once you find a jacket that fits you, ask for a label.

- Plastron: A half jacket worn under the jacket on the sword arm to provide extra padding.

- Chest protectors: Hard cups worn under the jacket by female fencers to protect the breasts.

- Glove: A glove is worn on the weapon hand only. The glove must be made of thick material and should have some padding on the back of the hand. The cuff of the glove must be worn over the jacket sleeve to prevent blades from sliding up inside. Try to find a glove that fits properly. If the glove is too large it may cause blisters. If it is too small it may restrict movement.

- Breeches: Breeches must extend from just above the waist to just below the knee. They are made of the same material as the jacket. Sweat or track pants are acceptable for fencing at the club. For safety reasons, shorts are not permitted.

Safety

Despite its violent history, fencing is a relatively safe sport. However, you must remember that, as in any other combative sport, injury is possible.

Most fencing related injuries are the result of people over-exerting themselves and pushing their bodies too hard. Fencing can also aggravate pre-existing conditions, particularly in the knees and wrists. Make sure you warm up and stretch before fencing. If you have any pre-existing injuries or problems, talk to your doctor before you participate.

Injuries resulting from hits with the blade are usually limited to bruises and the occasional welt. Occasionally a hit with an edge may break the skin and draw blood, even through clothing. More serious injuries are rare but do happen. Fatalities are almost unheard of. It's been said that fencing is safer than golf!

To help keep yourself and others safe, use common sense and follow these basic rules:

- Absolutely no sword-play without masks.

- Never touch or menace a person who is not wearing protective gear, or is not aware he may be touched.

- Do not attempt to free-fence until an instructor clears you to do so.

- Never use a broken or kinked weapon. If you break a blade or lose your tip, let us know immediately.

- Keep your blade under control. If you find yourself flailing wildly, stop, step back, and relax.

- If you wish to stop, signal your opponent by stepping back and waving your off-hand.

- If something doesn’t feel safe, don’t do it!

- Do not use a foil with a pistol grip unless a coach instructs you to do so. Used incorrectly, pistol grips increase the potential for injury, to both the opponent and the user.

- Do not attempt to fence épée or sabre unless you have received instruction in their use from one of the coaches. It can take anywhere from one to three years of experience in foil before one is ready to try épée or sabre.

- Do not attempt electric fencing until an instructor shows you how to use the equipment. Electric equipment is very expensive to replace should it be damaged or broken, and you may be held responsible for the replacement costs.

The Foil

The modern foil is a thrusting weapon: touches are made with the tip only, and must have character of penetration. The valid target consists of the torso, both front and back, and includes the groin. The limbs and head are considered off-target. Touches off-target stop the action, but no points are awarded. Hits made with the flat of the blade do not stop the action. Scoring in foil is governed by the rules of priority, which encourage correct technique and tactics when faced with a theoretically sharp blade.

The blade of the foil is square or rectangular in section, and should have a slight downward curve, which promotes even flexing of the blade while hitting. Foils may be up to 110cm long and weigh up to 500g. For the most part, our club uses French foils.

When fencing with the electric scoring system, foil fencers wear a body-wire and a lamé jacket covering the valid target. The tip of the foil is fitted with a small push button to detect touches. When a touch is made on the lamé, the body wire transmits an electric signal to the scoring box, thus registering the hit.

The first true foils appeared during the mid 17th century, in the form of blunted smallswords (see “History”). The foil served as a practice weapon for the smallsword, and for many years technique in both weapons was essentially the same. Gradually the foil developed into a specialised weapon. Lighter, more flexible blades were adopted to make practice safer, and guards simplified to offer only the minimum protection required.

The French developed a foil with a figure-eight shaped guard, straight grip, and small pommel. The grip gradually changed from an oval section to rectangular, and later adopted the slight inward curve we see today. In the early 20th century, the figure-eight guard was replaced by the shallow, round cup used now.

Italian fencers retained the crossbar and arches of the smallsword, under a shallow, round cup. This hilt remains virtually unchanged.

With the reduced popularity of duelling near the end of the 19th century, the safe, friendly foil became the principle weapon of the fencing community. Fencing students displayed their skills at public demonstrations and amateur competitions while Masters fought for titles on the professional circuit. It is in this bloodless competitive atmosphere that fencing truly established itself as a sport.

The 20th century has witnessed continued simplification in foil technique and further changes in design. Orthopaedic (pistol) grips first appeared in the 1930s, and while shunned by classical fencers, offered more or less the same advantages and limitations as the Italian grip. Electric scoring was introduced in foil in the 1950s, making the detection of touches much easier.

| |

| Modern Foil Types: a. French Foil b. Italian Foil c. Pistol-Gripped Foil |

The Foil Target (shaded) |

Épée

The modern épée, like the foil, is used exclusively for thrusting. The entire body is considered valid target. Hits that land flat do not stop the action. Épée is not governed by the rules of priority; in the case of double touches both fencers receive a point.

Épées may employ any of the same types of grips used on foils. The épée blade has a “v” section, and should have a slight downward curve. Épées may be up to 110cm long and weigh up to 770g.

When fencing electric épée, fencers wear a body-wire, which leads from the weapon and plugs into the retractable reel. The weapon is fitted with a small push-button tip which, when depressed, registers a touch on the scoring box. No lamé jacket is required, as the entire body is valid target.

Through the late 18th century the popularity of wearing swords decreased. The smallsword, originally an ornament as much as a sidearm, gradually simplified into a more utilitarian weapon. The triangular thrusting blade, fitted to a simple guard and grip, fulfilled the needs of the few fencers who still took to the duelling grounds. In the mid 19th century the épée du combat was introduced by the French. Perfectly designed for duelling, the large bell-guard provided excellent protection for the weapon hand, and the stiff triangular blade caused small, but potentially lethal puncture wounds. Actually during this period, few duellists insisted on fighting to the death, but rather fought until one fencer demonstrated superiority, received a debilitating injury, or until both parties felt honour was satisfied. In many cases duels were fought simply to first blood. Masters advocated attacks which could end an encounter quickly without exposing the attacker to too much risk. Thrusts to the weapon arm, leading leg, or face were encouraged. Épée was practised in the same manner as actual duels were fought; in the event of double-touches, both fencers were considered blooded. Thus the modern épée does not employ the rules of priority. Duelling with the épée continued well into the 20th century, with the last publicised duel occurring in France in 1958. It ended when one combatant received a scratch on the elbow.

Originally practice épées were fitted with a pointe d’arrêt, a small three-pronged cap designed to snag clothing. Later, leather and rubber tips were adopted.

Electric épée was introduced in the 1930s. It is amusing to note that a 1942 épée manual by Giorgio Rastelli included special sections both on fencing with the electric weapon, and on duelling.

| |

| Modern Épée Types: a. French Épée b. Pistol-Gripped Épée |

The Épée Target (shaded) |

Sabre

The modern sport sabre is a cutting and thrusting weapon. The target includes the head, the torso ending at the hips, and the arms ending at the wrists. Hits off target do not stop the action. Sabre fencing is governed by the rules of priority.

The sabre is the only weapon of the three to employ a knuckle-guard to protect the fingers from cuts. The sabre blade tapers from a “Y” to a rectangular cross-section. Theoretically straight, the blade actually has a slight inward curve to promote even flexing when thrusting. Sabres may be up to 105cm long and weigh up to 500g.

For electric sabre, fencers wear lamé over the torso and arms, and an all-metal mask with a lamé bib. Any touch on the valid target with the tip or edge of the blade will register a hit on the scoring box.

The forefathers of the modern sabre first came to Europe via the Middle East and Central Asia. The curved eastern scimitar inspired the falchion and storta, Medieval and Renaissance cleavers. Gradually lightened, these weapons developed into the sabre proper. By the mid 18th century, the sabre proved itself a cavalry favourite. Early technique paralleled broadsword schools, with only slight variations due to the sabre’s curved blade. The heavy curved sabre remained standard equipment for warfare until the last cavalry charges were cut down by machine gun fire in WWI.

In the mid-to-late 19th century, Hungarian and Italian military fencers developed a lighter version of the sabre designed specifically for duelling. This weapon employed a curved blade, approximately ¾ of an inch wide, upon which the front edge, and top third of the back edge were sharp. The guard and knuckle bow provided excellent protection from cuts and thrusts to the hand. The weapon proved light, fast, and deadly.

Giuseppe Radaelli is considered the founding father of modern sabre technique. His 1876 text advocated slicing, circular cuts delivered from the elbow, and set up the basic sabre parry system we use today. Although a practical duelling manual, his book established the school which eventually developed into sport sabre practice. Early sabre instruction included the legs as valid target, describing correct offence and defence of the low-lines. Gradually the target was reduced, likely due to the inherent risks to the attacker while striking the low-lines.

Over the next few decades variations in the sabre school developed. French and American Masters advocated a thrust-only style of sabre fencing while the Italians and Hungarians retained the cut as the principal method of attack. By this time some Masters advocated cuts delivered from the wrist, rather than the elbow, as these were faster and left the attacker less exposed. Some fencers preferred straight blades to the traditional curved ones, and eventually these were widely adopted.

As duelling declined at the dawn of the 20th century, the sabre became a weapon of sport. When the rules for sport sabre were formally set down, they were based on those of the foil, thus priority was adopted for scoring.

Technique in the first half of the 20th century still called for realistic cuts, with both an incisive and percussive character. Eventually fencers moved away from slicing cuts, employing instead a light, quick pop-cut delivered by squeezing the fingers. The universally adopted straight sabre blade continued to narrow into the thin, light blade we use today. Electric sabre was introduced in the 1980s and refined through the 1990s into the simple system used now.

| |

| Historical and Modern Sabre Types: a. 19th Century "Radaelli" style Duelling Sabre b. Sport Sabre c. Electric Sabre |

The Sabre Target (shaded) |

Priority

Priority confuses a lot of people at first and can seem a bit weird. However there are reasons for it and it makes sense after a while. Both foil and sabre depend on priority for scoring.

Back in the days when fencers trained for real duels, Masters had to find ways to encourage correct tactics when students practised. Students didn’t find the blunt weapons used for training nearly as threatening as the real thing, and thus they often did things in practice which would be suicidal on the duelling ground. Masters devised a set of rules which rewarded the correct execution of attacks, and encouraged the correct defensive response when attacked. These rules are now referred to as priority.

Today priority functions to determine who is awarded the point in the case of double-touches, those hits which land at approximately the same time. It does so by examining which fencer acted or responded correctly in the given situation. It should be noted that in instances where only one fencer touches, priority is not an issue.

A fencer first establishes priority by attacking in a correct manner; that is, by extending the arm and continuously threatening the target until the touch lands. If a fencer attacks incorrectly, with a bent arm or by retracting the arm during the course of the attack, he does not have priority.

When a fencer is attacked, priority states that his first concern is to protect himself from the touch by blocking it (parrying). It is incorrect to attack into an incoming attack (counterattack), because by doing so the fencer still allows himself to be touched. A duellist might touch with a counterattack, but he would very likely be killed in the process. By parrying an attack, the fencer demonstrates control of the opponent’s blade, and establishes the right to hit back (riposte).

Thus, during an exchange (phrase of arms), priority goes from the initial attack, to the parry-riposte, to the parry-counter-riposte, and so on, until one fencer touches the other, or until there is a pause in the action. In the event of a double-touch, the point is awarded to the fencer who had priority at the time.

A fencer may choose to respond in a way outside the rules of priority, if he feels he can do so without getting touched. If a fencer attacks incorrectly or slowly, the opponent may choose to counterattack. In order to steal the point, the counterattack must prevent the initial attack from arriving, or land before the attacker starts the final action of his attack. Thus, if a fencer attacks with multiple feints (false attacks), the opponent may attempt a counterattack against the early stages of the action. If the counterattack lands before the final thrust, it defeats priority and steals the point. Counterattacks should be used sparingly and always be premeditated. To counterattack every time one is attacked is to hand the opponent a lot of free points.

It should be noted that if two fencers chose the exact same instant to begin an attack, and both touch at the same time, it is called a simultaneous action and no points are awarded.

To sum up:

A fencer can establish priority by:

- Extending his arm and continuously threatening his opponent’s target during the course of the attack.

- Successfully parrying an attack and riposting immediately.

A fencer can lose priority by:

- Retracting the arm or bending the elbow during an attack.

- Failing to land the initial attack (missing, landing flat).

- Being parried.

- Failing to riposte immediately after parrying.

A fencer can defeat his opponent’s priority by:

- Parrying the incoming attack.

- Denying target (causing his opponent to miss by retreating or by body displacement).

- Executing a successful counterattack (must land before the last action of the incoming attack).

In the case of foil hits that land off-target, the following rules apply:

- If the attacking fencer lands off-target, the action is stopped and no points are awarded, even if the attacker is hit on-target by a counterattack at the same time.

- If the defending fencer lands a counterattack off-target before the last action of the incoming attack, the action is stopped and no points are awarded.

- If a fencer executes a successful parry, but ripostes off-target, the action is stopped and no points are awarded, even if the initial attacker lands a renewed attack on-target at the same time.

- If both fencers extend and hit at the exact same time, and one lands on-target, and the other lands off-target, the action is simultaneous and no points are awarded.

In other words, an attack, which has priority, stops the action when it touches, even if it lands off-target.

The Bout

Modern fencing is always done in a straight line, back and forth. There is no sideways. Fencing is done on a piste or strip that is 14 metres long by 1.5 metres wide. The piste is divided along its length by a centre line, on-guard lines, and warning lines. When placed on-guard, each fencer has 5 metres behind him upon which to retreat. The fencers must stay on the piste during the bout. When fencers step onto the piste for a bout, they place their masks under their arms and salute each other with their swords. Then the fencers put on their masks and fence. After the bout, the fencers remove their masks, salute again, and then shake hands with their non-weapon hands. If someone is refereeing, the fencers also salute him before and after the bout.

At our club, most bouts are fenced to 5, 10, or 15 points (5 and 15 at tournaments). It is good manners to always acknowledge hits made by one’s opponent, and it’s nice to indicate where. If a hit is messy or has questionable priority (Was that flat? Did you get that one or did I?), both fencers should agree to discount it. When in doubt, throw it out!

After a point is scored, the fencers return to their on-guard positions in the centre of the piste. When the action is stopped due to a touch off-target, the fencers are put back where they were when the touch occurred.

When fencing with a referee, he will give commands as to when to start and stop fencing. He will also award points and figure out priority in the case of double touches. After the salute the referee will give the command “En garde!” Once both fencers are in position he will ask “Prêts?” (ready?), and then “Allez!” (go!), and the bout begins. Once a touch is made, either on- or off-target, the referee will call “Halte!” (stop!), and both fencers must stop fencing immediately. If the touch is good, he will bring them back to centre. If not, they will continue from where they were. This continues until one fencer reaches the required number of points. Once again, if a fencer is touched and the referee doesn’t see it, the fencer should acknowledge the hit. No one likes a dishonest fencer.

The Secret of How to be a Good Fencer, According to Club Founder, Don Laszlo:

Keep distance. Extend your arm. Take control of your opponent’s blade.

Holding and Manipulating the Weapon

Learning the correct method of holding the weapon cannot be over-emphasised. Developing an incorrect grip will forever limit a fencer’s ability to handle a foil with ease and accuracy. The foil is a lightweight weapon designed exclusively for thrusting, and therefore relies on finesse for effective use.

The handle of the foil is rectangular in section, and has a noticeable curve inward and downward. On most Club weapons, ‘up’ is indicated by the brand name on the guard cushion. The thumb lies flat along the top of the grip, and the first knuckle of the index finger is placed opposite the tip of the thumb, near the cushion. With the thumb and index finger holding the weapon, the grip is pressed into the fleshy part of the hand at the root of the thumb so that the pommel lies against the wrist. The remaining three fingers are then placed lightly along the side of the grip. The whole assembly is then rotated slightly from the wrist to a position of partial supination (palm up), with the thumb at a 45o angle to the vertical. The method of holding the weapon is said to be correct when an unbroken line can be observed from the elbow to the tip of the foil, and there is space enough between the grip and the palm of the hand to permit one finger. The hand must remain relaxed, gripping only enough to prevent the foil from dropping.

The foil is manipulated primarily by the thumb and index finger (manipulators), and assisted by the remaining three fingers (aids). We control the tip by alternately pushing and pulling with the manipulators, relaxing and squeezing with the aids as necessary. Controlling the weapon in this manner is referred to as “fingering.” Fingering can be practised by extending the arm and attempting to make small circles around a doorknob with the foil point. Concentrate on using only the fingers, keeping the wrist, elbow and shoulder still, but relaxed. In the absence of a foil, fingering can be practised with a pen.

In order to use this method effectively, the fencer must maintain a relaxed hold of the weapon, only tightening the grip when the blades come in direct contact. As a reminder, every time one assumes the guard position with a weapon, squeeze the grip tightly, and then consciously relax the hand.

| |

| Front View of the Correct Grip | Inside View of the Correct Grip |

The On-Guard Position

The ready stance in fencing is referred to as the on-guard position. In the correct on-guard position the fencer’s feet provide a stable platform, but allow for rapid movement forward and back. The correct placement of the feet not only assists in balance and manoeuvrability, but also ensures the correct angle of the hips, thus turning the torso in semi-profile.

The fencer’s feet should be a comfortable distance apart (approximately one and one-half shoe-lengths), with the weight of the body evenly distributed across the whole of both feet. Avoid any tendency to shift the weight to one foot or the other, or to lift the heels. The whole front foot, and the heel of the back foot should stand straight on the line of direction (as illustrated below). The knees are bent evenly and we “sit” in the guard position. Bending the knees allows the fencer to advance and retreat smoothly, and provides spring for a fast and powerful lunge.

The torso should be vertical and erect, avoiding any tendency to lean forward or inward. Every effort should be made to keep the posterior from swinging outward. The head is erect and faces the opponent. The eyes focus on the guard of the opponent’s weapon.

The sword-arm hangs in line with the shoulder, with the elbow floating a hands-breadth from the flank. The forearm is parallel with the line of direction, and from the elbow to the tip of the foil the line remains unbroken. In this position the area of target nearest the opponent is protected by the weapon and the arm. This position also allows for the fastest and most accurate extension of the arm during the attack.

The trailing arm is coiled up behind the head to keep it well clear of the blades. Pulling it back reduces the tendency of the body to hunch forward. In this position the arm also serves as a counter-weight during the lunge and recovery, and promotes even muscle development in the chest and shoulders.

| |

| Front View of the On-Guard Position | Inside View of the On-Guard Position Correct Placement of the Feet along the Line of Direction |

The Lines

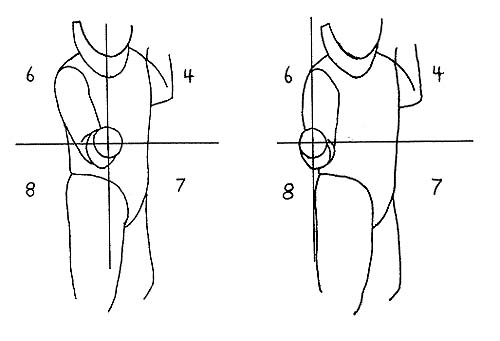

For the sake of reference, fencers divide the foil target into four quadrants, normally referred to as lines. The foil target is divided by horizontal and vertical boundaries, which pass through the guard of the weapon. We can then refer to the areas of the target, and any related actions, by whether they are above or below the guard, and inside or outside the guard. The divisions of the target may also be referred to by the parry number most commonly associated with the given line.

It is important to remember that the division of lines is entirely relative to the position of the guard, and therefore as the guard moves, so do the lines. Thus by moving the guard completely to one side or the other of the target, it is possible to “close the line.” Today most fencers prefer what is referred to as the “guard in sixth.” In this position the weapon and arm occupy the high-outside line (sixth), thus covering the target area closest to the opponent. This also covers most of the low-outside line (eighth), one of the most difficult areas to defend.

| |

| The Guard in Central Position | The Guard in Sixth |

| 4. Fourth – High-Inside Line 6. Sixth – High-Outside Line 7. Seventh – Low-Inside Line 8. Eighth – Low-Outside Line | |

A Brief History of Fencing

Fencing as we know it traces its history back to the mid 16th century. Various schools and disciplines of swordplay existed before this, but it is during this period that the first truly civilian sword appeared. This weapon was the rapier. The rapier developed as the result of changes made to the broadsword in the preceding century. Swordsmen found that the addition of a variety of bars to the simple quillons (cross-guard) of the weapon, provided greater protection to the hand. The most significant addition was a finger-ring, reaching from the fore-quillon up to the blade. This allowed for the safe placement of a finger over the fore-quillon, thus providing a more secure grip of the weapon and finer control. Other additions such as side-rings and the knuckle-bow were combined over time to create what is now referred to as a developed hilt.

Blades also underwent changes during this period. New combat demands and theories placed increasing emphasis on thrusting. Bladesmiths responded by producing narrower, stiffer blades, suitable for slipping through gaps in armour, and in some cases, for puncturing plate and chain-mail.

These changes, combined with the nobility’s desire to carry sidearms, produced the rapier. This early weapon, while heavier than the later “classical” rapier, was still suitable for civilian use. It served as a mark of social status, for defence against the hazards of travel, and as a means of settling matters of honour.

The rapier developed rapidly from the mid-16th century onward. Hilts continued to increase in complexity, and proved to be an excellent platform for ornamentation. Blades narrowed in an effort to provide lighter, more manageable weapons. These lighter blades were too fragile to be of much use on the battlefield. They lacked the mass necessary to cut down a fully armoured soldier, and would likely break against heavier swords and polearms. However, against opponents in everyday clothing, the rapier could inflict great damage with both edge and point.

Combat theory also continued to develop. In the 16th and 17th centuries the scientific thinking of the Renaissance and Enlightenment were in full swing, and this thinking helped develop several important theories in fencing. First: the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Second: by concentrating all of the strength and speed of the body into linear motion, a great force can be applied. And third: narrow, deep-penetrating wounds are generally more debilitating than broad, shallow wounds. The conclusion: the thrust is mightier than the cut. The thrust was faster because it travelled a straight line, rather than the arc travelled by the cut. The thrust could be made more powerful by elongating a step (lunging) as one attacked. Concentrating the energy produced by the lunge behind a narrow sharp point produced deep, potentially lethal wounds.

Thus, Fencing Masters placed ever-increasing emphasis on the thrust over the cut. It should be noted that the cut was not discarded entirely. Cutting theory, and advice on its most appropriate uses, remained part of the repertoire well into the 17th century. However, the emphasis on the thrust affected blade design, and as time passed blades continued to narrow. By this point blades lacked the mass needed to produce serious wounds with the edge. In fact, many later rapier blades lacked sharp edges entirely, indicating they were designed exclusively for thrusting.

Guard styles also changed during this period. Some designs included solid plates to increase protection of the hand against thrusts. These plates gradually grew to form the one-piece guard on the famous cup-hilt rapier. While the rapier continued to see practical use among devotees into the 18th century, from the middle of the 17th century the smallsword gained preference.

|

Basic rapier styles: a. Basic developed hilt b. Swept hilt c. Cage hilt d. Shell hilt e. Cup hilt |

The smallsword, like the rapier, developed to suit changing demands in fashion and practicality made by civilian combatants. Fencers found shorter, lighter blades to be more manageable for both offensive and defensive purposes. While this meant a loss of reach, the speed gained for parries and attacks was worth it. Because very little risk from cuts remained, guards were simplified, normally comprised of a double lobed solid plate, short arches and quillons, and a knuckle bow. Shorter, lighter blades combined with smaller, simpler hilts produced weapons of exceptional balance and utility. The smaller, lighter weapons were also more practical and comfortable for everyday wear.

The smallsword continued to change through the 18th century. On some later weapons the quillons and arches were eliminated, leaving only the shell-guard, knuckle bow, and a simple straight grip. It should also be noted that during the later days of the smallsword, blades with a triangular cross section became popular. A slightly fullered (grooved) triangular blade proved to be extremely strong and stiff for its weight, perfect for thrusting. This blade later reappeared in the épée du combat, father of the modern sport épée.

It is also during the mid 17th century that we see the first true foils. Essentially blunted smallswords at first, the foil soon developed into a specialised weapon, with a lighter, more flexible blade and a further simplified hilt.

The 18th century is arguably the most important period in the development of our sport. Fencing practice and theory of this era, with foil and smallsword, contributed greatly to the modern game. The wire fencing mask first appeared in the second half of this century. The invention of the mask is generally credited to the French Master, La Boëssière. Initially invented to make practice safer, the mask had the effect of allowing more daring, faster actions. This more energetic game, and the ability to practice without fear of injury, likely added to the appeal of fencing for fun’s sake.

The introduction of small reliable firearms during the late 18th century initiated a sharp decrease in the popularity of swords for duelling. Combat with pistols required much less training, and it has been suggested that the relative inaccuracy of these early guns aided their popularity. Duelling codes of the period allowed for the termination of a duel after a designated number of shots, or after one of the combatants received even a minor wound. Thus both duellists were more likely to walk away only slightly wounded, or completely unscathed. Duelling with swords survived among fencing devotees, and in the military.

Interestingly enough, with the development of more accurate firearms in the 19th century, duellists returned to the sword. Nostalgia for the glory of the Middle Ages and Renaissance also contributed to the resurgence of duelling. This return to the sword was marked by the creation of two new weapons designed specifically for the task.

Around the middle of the century, the French created the épée du combat. It featured the large protective cup of the late rapier, the simple straight grip of the French foil, and the triangular blade of the smallsword. This weapon quickly gained popularity throughout Western Europe. The Italians soon created their own version employing a grip based on that of the Italian foil.

Shortly after the introduction of the épée, military fencers created their own duelling weapon. The light duelling sabre was based on the heavier cavalry sabre used in war. The guard and grip resembled those of the heavier weapon, and the blade retained its distinctive backward curve, and front and partial back edge. However the blade was only about ¾ of an inch wide, making the duelling sabre significantly lighter than its heavier forefathers. Both Italy and Hungary are credited for its creation. Italian Masters also developed much of the early technique, which influences sabre practice to this day.

By this time fencing had already achieved sport status with the foil. Public demonstrations and competitions occurred throughout Europe and the New World. It wasn’t long before sportsmen adopted blunt versions of the two modern duelling weapons. While instruction for preparation for the duel continued into the 20th century, fencing solidified itself as a sport in the first Modern Olympic Games in 1896.

|

Smallsword, circa 1700 a. Pommel b. Grip c. Quillon block d. Quillon e. Shell guard f. Ricasso g. Arch h. Knucklebow |

|

Modern French electric foil a. Pommel b. Grip c. Guard socket d. Guard (coquille) |

Glossary

Fencing involves a lot of terms, some of which you have probably heard in other contexts. The fencing lexicon is a strange mix of English, French, and Italian. Some clubs favour one language above the others. For the most part, we use English at the U of C. There are far more fencing words than we’ve listed here, but these are the ones we use the most. Learning them will give you a better understanding of what we’re talking about, especially during instruction. And of course, if you hear us using a term you don’t know, just ask us.

- AFA

- The Alberta Fencing Association.

- Aids

- The middle, ring, and pinkie finger of the weapon hand, responsible for assisting the manipulators in controlling the weapon.

- Attack

- An offensive action in which the arm is fully extended and the weapon threatens the target. The attack is given initial priority.

- Attacks along the blade

- Those attacks in which the blade glides along, and controls, the opposing steel on the way to the target.

- Attacks on the blade

- Those attacks in which brief contact is made with the opposing blade to knock it out of line.

- Ballestra (It)

- A short jump forward in which both feet land at the same time. Used to quickly gain ground before a lunge, or to get a reaction from a jumpy opponent.

- Beat

- A crisp blow against the opponent’s blade that knocks it out of line.

- Bind

- An attack with constant contact of the blades, which forces the opponent’s blade diagonally from high to low line or vice-versa.

- Broken-time attack

- A compound attack in which the attacker pauses briefly in order to throw off the defender’s sense of timing.

- CFF

- The Canadian Fencing Federation.

- Character of penetration

- In thrusting weapons, the idea that, if the tip of the weapon was sharp, it would catch or pierce the flesh of the opponent. Hits that slide off, or land sideways would not penetrate. This does not mean hits must be hard, only that the tip should catch and the blade should bend slightly on impact.

- Circular parry

- A parry in which the tip of one’s sword scribes a full or partial circle around the attacking blade and carries it into a line other than where the attack was directed.

- Compound attack

- An attack that involves one or more simple actions executed as the arm is continuously extending. The compound attack maintains priority provided the attacker does not pull back his arm during the attack. Sometimes called a composed attack.

- Corps à corps (Fr)

- Bodily contact between fencers or the meeting of guards. A halt is called when a corps à corps occurs. If your guards meet, stop fencing immediately.

- Counterattack

- An offensive action made against an incoming attack in the hopes that it will land first or that one’s opponent will miss. The counterattack does not have priority.

- Counter-riposte

- A second attack made after parrying the opponent’s riposte. The riposte to the riposte.

- Cut-over

- A change of line, executed by passing the blade around the tip of the opponent’s weapon.

- Derobement

- Evasion of the opponent’s attempt to engage the blades, executed by disengaging under or over the blade.

- Direct

- A simple action, either an attack or parry, which is executed in the line the blade already occupies.

- Disengage

- A change of line, executed by passing the tip around an opponent’s blade near the guard.

- Dry

- Non-electric fencing and related equipment.

- Engagement

- When the blades are in contact with each other.

- Feint

- A false attack intended to force a reaction from one’s opponent (usually a parry). A feint is considered part of an attack and therefore has priority unless the attacker pulls back his arm or is parried.

- FIE

- Federation Internationale d’Escrime. The international governing body for our sport. The FIE standardises the rules for competition and sets equipment requirements. FIE-certified equipment means it is approved for high-level international competition. The FIE is based in Paris.

- First position

- The position taken for the salute. Standing erect, heels together at ninety degrees, weapon pointed at the floor, mask held under the trailing arm.

- Flank

- The target area under the weapon arm, from the armpit to the hip. The outside-low-line, protected by parry 8.

- Flat

- In foil and épée, a blow with the side of the blade, resulting in no valid touch, and no stop in the action.

- Foible (Fr)

- The weak part of the blade, nearest to the tip.

- Forte (Fr)

- The strong part of the blade, nearest to the guard.

- Glide

- An attack that slides along the opponent’s blade without moving it to a different line.

- High-line

- The target area on a fencer above the guard, meaning the chest and shoulders in foil.

- Indirect

- A simple action, either an attack or parry, preceded by a change of line.

- In-line

- When the tip of a weapon is pointed at the valid target.

- Inside-line

- The target area on a fencer “inside” from the blade, meaning the chest, stomach, and groin in foil.

- Invitation

- An opening given to an opponent to draw an attack. During instruction the invitation is used to indicate where the student should hit.

- Line

- An extended arm threatening the target (point-in-line) OR the direction of the attack.

- Line of direction

- An imaginary line passing through the feet of both fencers running parallel to the sides of the piste.

- Low-line

- The target area on a fencer below the guard, meaning the lower stomach, groin and flank in foil.

- Manipulators

- The thumb and forefinger, responsible for primary control of the weapon.

- Off-hand

- The hand which does not hold the weapon. Also referred to as the trailing hand.

- Opposition parry

- A parry in which contact with the opposing blade is maintained. The opposing blade is “held.”

- Outside-line

- The target area on a fencer “outside” from the blade, meaning the shoulder, back, and flank in foil.

- Parry

- A defensive action made with the forte of the blade that successfully blocks or redirects an incoming attack. The parry defeats the priority of the incoming attack.

- Passé (Fr)

- When the tip of the weapon slides off, or passes the target without digging in, resulting in no valid hit.

- Phrase of arms

- An uninterrupted sequence of action, ending with a pause or touch.

- Piste (Fr)

- The area of ground on which a fencing bout takes place. The piste is 14 metres long by 1.5 to 2 metres wide. Called a strip in English.

- Pistol grip (Orthopaedic grip)

- A grip shaped to fit snugly in the hand and offer more strength and control. Pistol grips come in a variety of styles and sizes. They are not recommended for beginners.

- Plaqué (Fr)

- When the tip of the weapon lands sideways without digging, resulting in no valid hit.

- Pommel

- The weighted knob at the back end of a weapon’s grip. The pommel holds the weapon together and provides a counter-balance to the weight of the blade.

- Pressure or Press

- Slight pressure put on the opponent’s blade in hopes of causing a parry or circular parry resulting in an opening in another line. Usually used as a feint, although sometimes used instead of a beat.

- Principle of defence

- In parrying, the use of the forte of the defending blade, against the foible of the attacking blade.

- Pronation

- Position of the hand with the palm facing down.

- Renewed attack

- A general term for a second attack launched immediately following the failure of the initial attack. The renewed attack does not have priority.

- Riposte

- An attack made by a fencer immediately following his parry. The riposte has priority over renewed attacks.

- Second intention

- A sequence of two attacks made by a fencer to take advantage of the opponent’s habitual reactions. The initial attack is made with the intent of allowing the opponent to parry and riposte in a predictable way. The opponent’s riposte is then parried and a counter-riposte delivered. Similar to thinking several moves ahead in chess.

- Sentiment du fer (Fr)

- Literally, “feel of the blade”. The ability to sense through the blade as if it is an extension of the body.

- Simultaneous attack

- When both fencers choose the exact same instant to initiate an attack, resulting in no points awarded in foil and sabre, and a point for each fencer in épée (double-touch).

- Supination

- Position of the hand with the palm facing up.

- Tac-parry

- A parry which crisply beats aside the attacking blade. Also called a beat-parry or detached-parry.

- Tempo

- A single tempo or “fencing time” is the time it takes to perform one simple action (eg. extend the arm). The correct plural is Tempi.

Recommended Further Reading

There are a lot of fencing books out there, and some are better than others. If you come across a book not listed here, feel free to ask us about it. Odds are one of us has read it. Otherwise we recommend the following. Check both amazon.ca and chapters.ca for prices. Some local bookstores carry the occasional item as well.

For fencing technique: Foil Fencing by Muriel Bower. A classic now in its eighth edition, this book most closely parallels what we teach at the U of C. Earlier editions are good too, but may be slightly out of date.

For fencing history: By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions byRichard A. Cohen. Interesting and extremely informative, the best contemporary history available.

For general fencing knowledge: Know the Game: Fencing by British Fencing. A handy little introduction to the sport, recommended for anyone even thinking about trying it.Purchasing Equipment

The Club’s preferred dealer is Fencing Equipment of Canada, located here in Calgary. FEC sells Leon Paul equipment, and usually has a good selection in stock. Items such as jackets and masks may need to be ordered. Beginners’ Kits, which include all items required for dry-fencing at the club, are available at good prices.

Shopping is by appointment: phone 281-1384

Most prices are listed on their website at www.fencingcanada.ca

If you have any questions or concerns about the beginner’s course, or fencing in general, feel free to contact your instructor, Nathan Bell.

Written and illustrated by N. Bell

Edited by V. Bjerreskov

Home | About Us

| About Fencing

| Links | Photo Gallery

Image Bank | Reviews

| Fencing Fun | Contact Us