It has become increasingly apparent over recent years that the North African coast played a role in the Late Bronze Age trade network. Pottery types from across the Mediterranean discovered at ZUR and Marsa Matruh indicate that the trade routes of the period took in at least part of the coastline.

On the basis of similar pottery finds at the port of Kommos on the south coast of Crete, combined with current and wind data, clockwise and anti-clockwise trade routes taking in North Africa have been proposed (fig.i) (Cline 1994:91-93; Kemp & Merrillees 1980:269-271; Warren 1995:10-11; Watrous 1992:176-178).

Whilst North Africa was certainly a regular port of call for Late Bronze Age mariner, the point from which they would have departed or arrived on the coast is uncertain. The shortest route between Africa and Europe is between Crete and Cyrenaica, on the Libyan coast, a distance of about 300km. This is the route that later Greek settlers followed in the 7th century BC (Boardman 1994:142-143; Knapp 1981:261). However, surveys have failed to find any conclusive evidence to indicate there was any contact between these regions in the Late Bronze Age (Boardman 1968; Carter 1963; Knapp 1981; White & White 1996). Whilst future investigation may uncover new information, the only evidence of Late Bronze Age contact with North Africa discovered so far has been at ZUR and Marsa Matruh.

The prevailing north-west wind of the summer sailing season favours landing in the general region of Marsa Matruh (and ZUR) if coming from Crete; perhaps this was the route (c400km) that was favoured by mariners making the journey to North Africa in the Late Bronze Age.

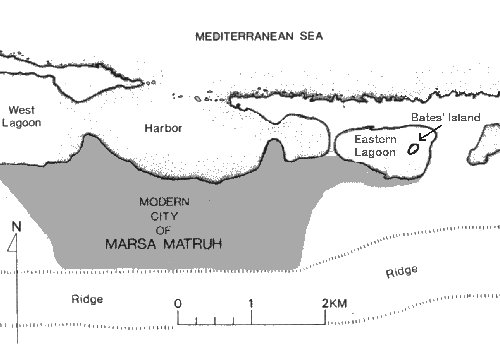

Foreign contact with this region of North Africa in the Late Bronze Age was first proposed by Oric Bates (1915, 1927) on the basis of evidence he located at Marsa Matruh, on a small islet at the eastern end of a lagoon in the town's harbour (fig.ii). It was subsequently re-investigated in the late 1980s by Donald White (1985, 1986a, 1986b, 1987, 1989, 1990a, 1990b, 1999b). Now known as Bates' Island in archaeological circles, it measures 135m north-east to south-west and 55m north-west to south-east, with a maximum elevation above modern sea-level of just over 6m (White 1986a:59). It has produced evidence dating from the modern period back to the Late Bronze Age.

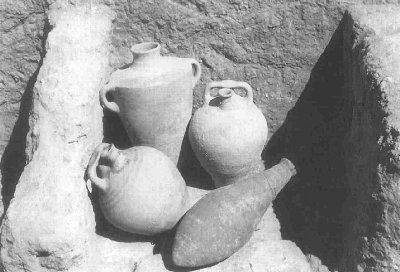

The Bronze Age material from Bates' Island consists mainly of pottery sherds, of which about 80% were Cypriot, with the remaining 20% being made up of Egyptian, Palestinian and Aegean wares (Hulin 1989; White 1986a:79-81, 1990:3). These finds suggest an occupation date for the island largely in 14th century BC but extending into the 13th (Hulin 125-6; White 1989:113-114).

In addition to the ceramics, several bronze artefacts were discovered, along with crucible fragments, slag and bronze scraps, indicating that metal-working may have been taking place on the island in antiquity (White 1986a:79, 1989:113).

The general function assumed for the island is as a revictualing station for merchant ships, where mariners could take on board supplies after reaching the coast from Crete or perhaps before setting off for the island (White 1986a:83-84). It cannot be said for certain who may have resided on the Bates' Island, and considering its size, it can only have been a very small population. White (1986a:83) suggested a possible close association with Cyprus, but this cannot be assumed simply because Cypriot pottery dominates the finds.

The island may also have been some

form of trading station where foreign merchants traded with the local Libyans. A

small amount of the pottery discovered on the island has been classed as of

local Libyan origin (Hulin 1989:121-123). This, along with several possible

Libyan graves located by Bates (1927:137-40) a mile and a half south-east of the

island, has led to the suggestion that whilst residing locally during the

summer, enjoying the more temperate coastal climate, the Libyans engaged in

trade with the islanders (Conwell 1987: 28-29; White 1986a:79, 1990:11).

Further supporting this idea are a number of fragments of ostrich eggshell located on the island. Ostrich egg shells, along with feathers, were the Libyans only prestige trade commodity, which they are portrayed as bringing as tribute in Egyptian in tomb-paintings (fig.iii) (Conwell 1987).

Thus, the local Libyans may have been trading ostrich products with those individuals residing on Bates' Island, for their intrinsic value and also perhaps for food. In addition, other foodstuffs as well as water may have been traded by the Libyans for various goods and worked metal items, which were probably beyond their capability to make (Conwell 1987:33-34; White 1986a:84, 1990:11).

The pottery suggests that the occupation of Bates' Island ended in the 13th century BC. This might coincide with the founding of the fort at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham in perhaps c.1280BC, or thereabouts. Any control that the Egyptians sought over foreign contacts by inserting themselves here is unlikely to have gained them access to anything they did not already have. However, controlling the region's foreign trade contacts may have been strategically sound and another method by which Egyptian security could be maintained.

Before the Egyptians imposed their presence in the Marsa Matruh region, any contact between the local Libyans and foreigners would have gone unchecked. Perhaps it was concern that the Libyans may have had access to weapons or other dangerous goods that prompted the Egyptians to take control in the region, which they did by imposing themselves as middlemen to regulate trade and restrict what the Libyans had access to.

The Egyptians imposed trade controls in a similar fashion elsewhere in their territory. In the Middle Kingdom, Nubian traders coming up from the south wishing to do business in Egypt were obliged to conduct it through the fortress of Mirgissa, ancient Iken (click here for a map, or here further details on the southern forts) (Smith 1991b:126-128, 1995:41-43). Similarly, in the 7th century BC, all Greek trade was directed through Naukratis in the western Delta - click here for a map (Lloyd 1983:329).

The system of regulation would have been enforced through forts like that at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. The foreign pottery found here strongly suggests that the fort did indeed have some involvement in the Late Bronze Age trade network (fig.iv). One could suggest that this material need not necessarily have been brought to the site directly by foreign merchants coming to the region, but could simply have been imported to the fort from the Nile Valley, as part of its state supplied provisions. Whilst this is possible, the identical material found at Marsa Matruh, as well as the circumstantial evidence discussed above, makes it unlikely that the foreign wares from ZUR can be dismissed in this way.

Furthermore, The Southern Building at ZUR, the possible "massebah" temple, may also provide evidence of the fort's role in regulating regional trade. If it was, as suggested, designed to mimic non-Egyptian religious practices, perhaps it was founded to encourage foreign merchants to land at/near the fort rather than elsewhere on the coast. By doing this, they could then make offerings to ensure a safe onward journey or give thanks at having successfully made it this far.

|

If Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham does indeed represent a focal point for trade, what might be the significance of the foreign wares discovered there? How exactly the foreign pottery came to be at the fort is uncertain. It might represent the remains of a straightforward exchange, with the Egyptian garrison supplementing their state supplied provisions with some of the exotic goods carried by visiting merchants. Alternatively, perhaps the goods were extracted, formally or informally, from merchants as a duty or some form of tithe. A similar system operated at Elephantine in the 5th century BC (Yardeni 1994), and perhaps such a system existed somewhat earlier. Alternatively, they might represent the Egyptians' commission for acting as middlemen in exchanges between Libyans and merchants. Extracting goods in this way from foreign merchants and/or Libyans who came to trade may have been one method in which to underwrite the costs of maintaining these garrisons and another reason why the Egyptians may have desired to secure control over regional trade. Thus, rather than being dependent on the central state for all their requirements, the fortresses may have been self-sufficient to some extent, using locally available resources (either truly local or those brought in by foreign merchants) as both the Nubian fortresses and the Egyptian garrisons in Palestine (see fig.v) appear to have done (Ahituv 1978:96; Smith 1991a:93-94, 1997:77-81; Weinstein 1981:15).

|

Whether any of the other Egyptian fortresses along the coast were involved in foreign trade is not known. Watrous (1992:177) suggests that they would have all been ports of call for Late Bronze Age mariners, and this is a definite possibility. The reference to the Canaanite deity Horoun at el-Gharbaniyat might tentatively be said to suggest that it had some foreign contacts, perhaps with vessels travelling into Lake Maryut towards the Delta. However, until these sites are further investigated, one cannot draw any definite conclusions.

With the new system of trade regulation in place, in order to gain access to goods that the merchants brought, the Libyans may have found themselves obliged to come to the fort. Here they could trade perhaps either directly with foreigners or through the Egyptians. Numerous fragments of ostrich eggshell have been found at ZUR, suggesting a Libyan presence there.

If the local Libyans were obliged to trade through the North African fortresses, future archaeological investigation may seek to identify clusters of their encampments in the vicinity of each fort. This would be very similar to the way in which camps of the Shasu bedouin of the northern Sinai have been found around the forts of the "Ways of Horus", which regulated their movement but upon which they were dependent for supplies and protection (Caminos 1954:293-296; Oren 1987:77). Nothing like this has yet been noted on the Mediterranean coast, but it is perhaps worthy of further investigation and may prove to be an interesting model for future work. However, one should note that although the "Ways of Horus" forts may have controlled overland trade, they probably had less involvement with maritime traffic, as all but one of the sites of New Kingdom activity is situated a distance from the coast (Oren 1987:77). North Sinai coastal waters can be treacherous and perhaps sailing vessels preferred to avoid them (Oren 1987:114). Such differences between systems that seem otherwise to have been very similar illustrate the dangers of assuming what was true of one region was automatically true of another.

|

If Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham did play a role in the regulation of Late Bronze Age trade, why did the Egyptians choose to found the fort 20km west of Marsa Matruh, where activity appears to have been focussed? Perhaps the fort was established at ZUR in order to defend a valuable water source. But, countering this, there must also have been some water supply in the vicinity of modern Marsa Matruh to support those who resided (even sporadically) on or near Bates' Island, even though its location is not known today. Perhaps there was another Egyptian settlement at Marsa Matruh directing trade and controlling the water supply of which we know nothing. Alternatively, perhaps the Egyptians did not feel it necessary to impose themselves at Marsa Matruh at all because they did not see Bates' Island as significant. Perhaps archaeologists have overplayed the role of this site as, until recently, it was the only place where evidence of foreign contact with the region in the Late Bronze Age had been found. Although the evidence from this site certainly represents foreign contact with the region, how extensive this contact was is debatable. The pottery dates from the 13th and 14th centuries BC and, according to the excavator, spans 80 to 100 years (White 1990:6). However, there is nothing to suggest that it represents continuous or even regular occupation. In fact, it may indicate nothing more than a few isolated landings. All things considered, Bates' Island really does not offer much to attract occupation. It is exposed, has no water source and is small, and may have been even smaller in the Late Bronze Age due to a higher sea level (Bakr & Nibbi 1998:101-102; White 1996b:330, 1989:94). Perhaps Bates' Island was not as important in the past as it is for today's archaeologists. Hopefully, further work in the region will clarify the relationship between the fort at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham and Bates' Island and how they both fitted into Late Bronze Age trade. |