Until recently there has been little comprehensive archaeology on Egypt's western frontier; what has been done has been largely sporadic and inadequate. With this review of the archaeological material, it will soon become apparent how little hard evidence regarding the nature, role and activities at the proposed fortress sites there actually is. Only with the work at ZUR, and more recently at Kom el-Abqua'in, has this begun to change.

To see information about a specific site, click it's name below or read on:

El-Alamein lays over 200km east of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. It is most famous as the site of the major World War II battle, and it was at this time (1941) that evidence of a much earlier military presence was discovered, being a number of stone fragments dating to the reign of Ramesses II (Brinton 1942; Habachi 1980:19-23; Kitchen 1996:293-294, 1999:329-330).

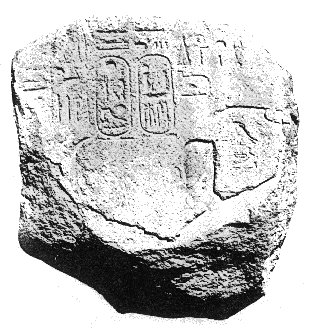

The principal remains were several pieces of a red granite stela and its base. The upper part of the stela measured approximately 90cm in height when found. It seems to have been originally decorated on both faces and sides, but only one face survives reasonably intact, showing Ramesses II smiting one or more foes accompanied by the god Shu (fig.i).

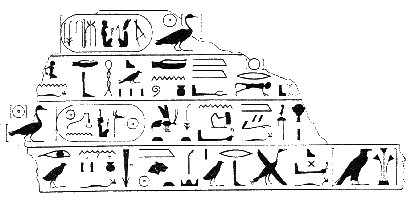

The lower section of the stela is about 80cm high and 94cm wide. One side bears a fragmentary inscription describing the king as beloved of a god whose name is lost, whilst another face bears a similarly damaged text praising his power. On a third face (fig.ii) is a slightly better preserved inscription that describes Ramesses II causing some enemies to have "fallen in confusion" and be slain. Habachi (1980:20) believed he could make out references to these enemies (whose name is lost) being accompanied by their families, although he admits that this portion of the text is somewhat difficult to make out, and Kitchen (1996:294) makes no mention of this. More important is the phrase, "He (Ramesses II) plundered the Rebu-land in the moment of his power". When discovered, this was the earliest known reference to this group (Brinton 1942:163-164) - a contemporary reference has now been found at ZUR.

A further block of granite formed the stela's pedestal. It is badly defaced but bears traces of the titles and epithets of Ramesses II. Another small granite fragment was found 5km east of el-Alamein. Although Rowe (1954:498) suggested that this might represent a fortress in its own right, this seems unlikely; it almost certainly comes from el-Alamein. This block includes the phrase "the land of the Tjehenu", although in what context it is referred to is impossible to tell.

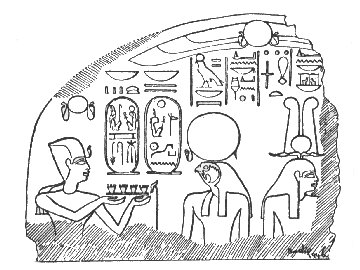

Also found at el-Alamein was the upper left portion of a limestone stela, 80cm high, upon which Ramesses II is shown making offerings to Re-Horakhti (fig.iii). An image of Ptah-Tenen survives at the point where the stela breaks and it is likely that there was a second image of the king on the lost part offering to this god for the sake of symmetry.

Shortly after their discovery, most of the blocks were moved to the police station at Burg el-Arab for safety (Brinton 1942:80; Habachi 1980:19). Whilst they were being excavated, traces of a wall were discovered, but its association with the Pharaonic blocks was never investigated or confirmed (Brinton 1942:78). Whether or not the remains were found in situ was never explicitly stated by any of those who looked at the material. However, the fact that all the fragments were found in such close proximity to each other, particularly the granite stela and its base, suggests that they had not moved far. If they were indeed in situ, what might they have been part of?

In conclusions, the evidence for the existence of a fortress here is only circumstantial. For example, the bellicose nature of the surviving inscriptions is somewhat similar to those of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. Its location also might suggest that it was a fortress, as few other settlement types would be located in such a remote spot. However, no systematic investigation of the site has ever been undertaken to confirm what was happening here in the New Kingdom. A good reason for this includes the fact that the area was heavily mined during World War II, which understandably deterred excavation. It may be now be impossible to locate any remains dating to the Ramesside period because the region has undergone a building boom in recent years. Although material of the Graeco-Roman period has been investigated in the wake of this construction work (Daszewski 1995; Leclant & Clerc 1988-1998), nothing dating to the Late Bronze Age has been discovered to help clarify what might or might not have been going on here.

It was in the vicinity of this site, 23km east-south-east of el-Alamein, that one began to enter the cultivated land of the Maryut district, a stark contrast to the barren Western Desert beyond (De Cosson 1935:120). Khashm el-Eish, or the "Beginning of Plenty", is located high up and possesses a good view of the desert to the west (De Cosson ibid.). Such a location offers strategic significance and was exploited in the Graeco-Roman period with the construction of a fortress here, and De Cosson (1935:31, 121) suggests that this may represent the point known as the "beginning of the Earth" and the location of the "fortress of the west" in the ancient Libyan war texts. Whilst such a notion is appealing, there is no firm archaeological evidence to support any activity here in the New Kingdom.

Both De Cosson (1935:26) and Rowe (1953, 1954) suggest that this site, some 40km along the coast from el-Alamein, may have been the location of fortifications from the time of Ramesses II, although there is no archaeological evidence to support this. Rowe (1953:134) mentions some large red granite blocks that he states to be "obviously part of a local Ramesside fort". However, as he offers no further details of these blocks, just how valid his conclusion was remains a mystery.

De Cosson bases his conclusion on the fact that this was the site of a later fortress. This took the form of a stone-built enclosure, probably fairly late in date, either Ptolemaic or Roman (De Cosson 1935:115-116; Leclant & Clerc 1992:217).

Whether a fortress existed here as early as the time of Ramesses II is not known, although such a location would have made good strategic sense. Any fort here would have barred the route to the north-west corner of the Delta that ran along the narrow strip of land, known as the Taenia ridge, on the northern side of the freshwater Lake Maryut/Mareotis, that have extended to this point in antiquity before it shrank to its current size (fig.iv) (De Cosson 1935:26, 70-82, 116).

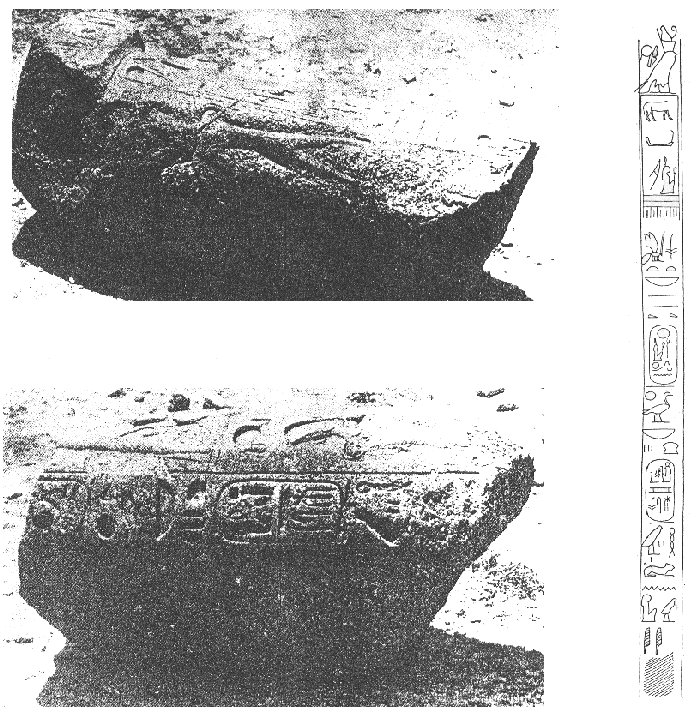

El-Gharbaniyat is about 50km east of el-Alamein. De Cosson (1935:31, 127-128) described there as being here the "…traces of an ancient Egyptian mud-brick building, and…an immense granite column finely inscribed with the cartouches of Ramses II (sic)…Unfortunately the column is broken..."; he concluded that this site may have been a fortress erected by Ramesses against the Libyans, possibly that known as the "Fortress of the West". Brinton (1942:80) was also confident that this site represented a fortress and saw the red granite column in three pieces (fig.v); no other stonework was visible (Habachi 1980:23-24).

The fragments, later removed to Burg el-Arab police station for safety, formed a column 3.5m high, bearing two vertical lines of inscription that concluded by describing Ramesses II as "beloved of Horoun" (Habachi 1980:24).

Why would we find a reference to a primarily Canaanite deity here? Habachi (1980:29) suggested that the presence of this god may indicate that troops from the eastern Delta or even Palestine were stationed here, perhaps part of a deliberate policy of Ramesses II of settling captured foreign soldiers well away from their actual homelands.

This policy is recorded in a text in the Great Temple at Abu Simbel which describes the king as settling the Shasu bedouin of the east in the west, Nubians in the north and Libyans in the east (Kitchen 1996:67, 1999:118). Such a policy would have been intended to negate the possibility of foreign troops joining with their fellow countrymen in any revolt against Egyptian rule.

Perhaps one could suggest that the so-called "massebah" temple (Southern Building) at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham might represent something similar. However, if the idea of the policy was to culturally assimilate these foreigners into the Egyptian way of life, it hardly seems likely that Ramesses would have gone to the trouble of constructing monuments to foreign gods that would have maintained cultural barriers. Perhaps we must look elsewhere for an explanation of these feature; this is discussed in the next section.

In conclusion, this site has been subject to little archaeological work but the evidence indicates that a structure of Ramesses II may well have existed here, although its precise nature remains to be determined. Further work here would be rewarding, perhaps producing evidence in the form of inscriptions or defensive structures that would confirm whether or not this site was the location of a further fortress.

Kom el-Idris, ancient Marea, is located 23km north-east of el-Gharbaniyat, and about 40km south-west of Alexandria. The site sat upon the shore of Lake Maryut and possessed a flourishing port in antiquity, linked to the Nile and Mediterranean via canals (Gabel 1999:465-466; Petruso & Gabel 1983).

Archaeological work at the site has shown most remains to date to the Byzantine period (4th-7th centuries AD) (Gabel 1999:465), although some tombs from Dynasty 26 (c.664-525BC) into the Graeco-Roman period have been excavated (Leclant 1978-1980, 1983, 1984; Leclant & Clerc 1985-1987, 1992, 1994). There is no conclusive evidence of any earlier remains although Rowe (1953:130-131) claimed that a number of blocks of stone at this site were "doubtless pharaonic in origin". He suggests that this site may have been the location of "the mountain of Up-Ta" and the "Town of (Ramesses III) is the Repeller of the (Tjemehu)", mentioned in the Libyan war inscriptions of Merenptah and Ramesses III, although he offers no evidence to support his claims (Rowe 1953:130, 1954:487).

This site would have been a strategic location where forces could be mustered by water from any part of the Nile Valley to meet a threat from the west (De Cosson 1935:132). Herodotus claimed that Psammatichus II (c.595-589) kept a garrison at Marea in the 6th century BC as a defence against the "Libyans" (Legrand 1948:85-86). But whether there was a fort here in the New Kingdom is, as yet, impossible to establish.

This site was the location of the Pharaonic settlement "Ra-Kedet" which would later become Alexandria (Kolataj 1999:130). Rowe (1953:137, 1954:486) states that ancient Rhacotis was "a strong frontier fort in the Western Delta at least since the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty" and "in the reign of Ramesses II it was still a great fort", being the "chief frontier fortress". Unfortunately, he fails offer any substantial evidence to support this. He does mention remains at the site dating to the reigns of several New Kingdom rulers, from Tuthmosis III through to Ramesses IX (Rowe 1954:485), but there is nothing to indicate that this represents any type of fortification or that they are not all re-used. Similarly, whilst recent surveys of the submerged remains of the ancient lighthouse at Alexandria (erected between 280-278BC) revealed additional traces of Pharaonic activity, including columns, obelisks and sphinxes, some bearing the names of Seti I and Ramesses II, evidence suggest that they were transported there from elsewhere (e.g.Helipolis) much later, in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (Khalil 2002:16).

However, there are sphinxes of Ramesses II at the site of ancient Rhacotis which do appear to be in situ (Khlail 2002:17; Kadous 2001:198-199). There are also submerged harbour works off the coast which have been dated by their form and method of construction to the Late Bronze Age (Khalil 2002; Jondet 1912).

A fortress at Rhacotis could have served to defend the Canopic Nile against intruders, it being one of the main entrances to Egypt, with access to freshwater from Lake Maryut (Khalil 2002:19). Thus, it would have been strategically sound to establish defences here. Strabo mentions the fact that the Pharaohs established a garrison here to defend the town against foreign intruders coming from the sea, although he doesn't specify which Pharaohs (Khalil 2002:7).

Although there is evidence to suggest Late Bronze Age activity at Rhacotis and that a fortress here would have been strategically sound, like many of the other proposed fort sites, there is no hard evidence that one ever existed.

Into the Western Delta...

Ezbet Abu-Shawish lays approximately 20km east-south-east of Kom el-Idris (Marea). The actual archaeological evidence for Pharaonic activity at the site is limited. Rowe (1953:140) states that Tuthmosis IV and Merenptah were active here, although he does not elaborate on this.

Rowe (1953:140, 1954:487) suggests that this site may be the "castle of Merenptah which is in (Per-Iru)", and that this was later renamed the "House of Sand", as mentioned in the war inscriptions of Ramesses III. His main reason for this identification seems to be that in the invasion records the distance between the "House of Sand" and the "mountain of (Up-Ta)" (according to him, Kom el-Idris) is said to be 8 iters (c.16km) (Rowe ibid.). Conveniently, this is very nearly the distance from Ezbet Abu-Shawish to Kom el-Idris. Rowe (1954:487) takes this as "practically confirming" his identification of the two sites. However, there is no hard evidence to support the idea that there was a New Kingdom fortress here. The site's identification as the location of a fort seems entirely spurious.

Rowe (1954:499) proposed that this site, 10km south-east of Ezbet Abu-Shawish, could be the location of a fort named "the castle of Ramesses II beloved of Amun beloved like Tum on the Western Waters", mentioned on a large scarab (Gardiner 1918:131). Rowe (ibid.) also suggests that El-Kurum El-Tuwal may be the "fortress of the west" under Merenptah or the town of Ramesses III on "the western road and western canal" as mentioned in Papyrus Harris I (Breasted 1906b:170-171), a document written in the time of Ramesses IV referring back to events of the previous king's reign.

The "western waters" and "western canal" may be equated with the former Canopic Branch of the Nile that once flowed to the west of the modern Rosetta branch, discharging into the Mediterranean at Canopus (fig.ii) (Gardiner 1918:130-131). However, it could also refer to Lake Maryut, in which case numerous sites in the region could be said to be on "the western waters". I do not believe that using this description alone is a convincing argument to link any site on the ground with those mentioned in the texts. This is especially true in this case as there is no archaeological evidence of New Kingdom activity at el-Kurum el-Tuwal; the earliest material dates to the Ptolemaic period (De Cosson 1935:147; Eilmann et al. 1930). Again, the identification of this site as ever having been the location of a fortress seems pure speculation.

Karm

Abu-Girg is almost 50km south-east of el-Gharbaniyat. Some fragments of stone

with hieroglyphic inscriptions and the base of a red granite obelisk bearing the

name of Ramesses II were located here by Breccia in 1912 (fig.vi) (Brinton

1942:80; De Cosson 1935:147-148; Habachi 1980:25). Habachi (ibid.) believes it

improbable that Ramesses built at such a distant place as this and that it is

more likely the blocks, which are somewhat cut down, were brought here from

elsewhere to be reused in the construction of a later monastery. There is no

real reason, however, why Ramesses II would not have built here. Rowe (1953:140,

1954:498-499) believed the material was in situ and he proposed that if el-Kurum

el-Tuwal was not equivalent to the ancient toponyms he suggested, then perhaps

this site might have been. Whilst still speculative, at least there is some

evidence of Ramesside activity here!

Karm

Abu-Girg is almost 50km south-east of el-Gharbaniyat. Some fragments of stone

with hieroglyphic inscriptions and the base of a red granite obelisk bearing the

name of Ramesses II were located here by Breccia in 1912 (fig.vi) (Brinton

1942:80; De Cosson 1935:147-148; Habachi 1980:25). Habachi (ibid.) believes it

improbable that Ramesses built at such a distant place as this and that it is

more likely the blocks, which are somewhat cut down, were brought here from

elsewhere to be reused in the construction of a later monastery. There is no

real reason, however, why Ramesses II would not have built here. Rowe (1953:140,

1954:498-499) believed the material was in situ and he proposed that if el-Kurum

el-Tuwal was not equivalent to the ancient toponyms he suggested, then perhaps

this site might have been. Whilst still speculative, at least there is some

evidence of Ramesside activity here!

Once again, precisely what the remains here represent is difficult to determine. In antiquity, this site would have sat only a short distance from the edge of the now vanished Lake Maryut. If a fortress was located in the vicinity, it may have been intended to defend the well-watered route around the lake. Only additional evidence will be able confirm or discount whether Ramesses II was active here.

Apart from Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, this is the only site to have produced any conclusive evidence of being another Ramesside fortress.

Since 1996, the site has been investigated by Dr Susannah Thomas of the University of Liverpool. Her website contains full details of the site's history and the work that she is undertaken: Tell Abqua'in.

For further information, see: Daressy 1904; Habachi 1952, 1980; Kitchen 1996

El-Barnugi lays 26km south-east of el-Abqa'in. The evidence here, including tombs and pottery, points primarily to occupation in the Roman period (Coulson & Leonard 1979:163, 1981:70).

However, two stone-built tombs of the Middle Kingdom (Dynasty 11) were excavated at the site at the beginning of the 20th century (Edgar 1907), and the sebbakhin uncovered two inscribed blocks, one of Tuthmosis I and the other of Ramesses II, the latter possibly being part of a column, doorway or the back pillar of a statue (Edgar 1911:278; Kitchen 1999:328; Porter & Moss 1934:49).

In the late 1970s, the Naukratis Project, a survey of occupation in this region of the western Delta, visited the site but was unable to find any other evidence of Pharaonic occupation bar the rim of an alabaster canopic jar (Coulson & Leonard 1979:163, 1981:70).

The evidence, such as it is, reveals little regarding New Kingdom activity at el-Barnugi. Kitchen (1999:328) suggests that the Tuthmosis III block might indicate that this king founded a fortress here but, as he points out, it is just as likely that it was usurped from another site. Thus, there is little to convince us that any New Kingdom defences existed at el-Barnugi.

Located 12km south-east of el-Barnugi, Kom Firin has undergone little archaeological investigation. The site was visited by Petrie and Griffith in the 1880s. Petrie (1886:94) recorded that the southern half of the site (an area of approximately 800 by 800 metres) was surrounded "with a great wall of unbaked bricks", which had suffered at the hands of the sebbakhin. At the centre of this enclosure he noted the remains of a citadel standing on an artificial mound of sand, and to the south-east a large temple, whilst outside, to the north-east, he described two further enclosures (Petrie ibid.). Griffith (1888:83) identified two enclosures, one that seems to represent Petrie's temple, and another located some distance west of the first "entirely on the sand of the desert". The two descriptions vary somewhat and are not entirely easy to compare, especially as no plans accompany them.

Some years later, Edgar (1911:277) visited the site to investigate two column bases inscribed with the titles of Ramesses II that had been located by the sebbakhin. These were limestone, with a diameter of 165cm and, as far as is possible to determine, were found in situ, 255cm apart, in the centre of what Petrie had called the citadel (Edgar 1911:277-278).

The Naukratis Project examined the site as part of its investigations in the late 1970s (Coulson & Leonard 1979:158-162, 1981:70-73, 1982a:213-220). Little survived of the features recorded by the earlier archaeologists beyond some scattered, red granite blocks and fragments of the mud-brick enclosures (Coulson & Leonard 1979:159, 1981:71; 1982a:215). Of the central citadel, parts of a circular tower had been exposed by the sebbakhin along with sections of a nearby mud-brick wall, running east-west for about 25 metres, although much of this has now been destroyed (Coulson & Leonard 1979:159, 1981:71-2, 1982b:377). Nothing could be reconstructed from these miscellaneous remains.

During his visit, Petrie (1886:94-95) had located certain artefacts that suggested the main period of occupation on the site was the 26th Dynasty (c.664-525BC). The column bases described by Edgar however indicate that the site existed from at least the New Kingdom, and at at Silvagou, 2km west, there is evidence of other Late Bronze Age activity. This takes the form of two Mycenaean style stirrup jars and four clay anthropoid coffins of a type commonly associated with the Philistine "Sea Peoples", found on Palestinian sites such as Tell el-Far'ah or Beth Shan (Coulson & Leonard 1979:168, 1981:73; Dothan 1979:101-104). As the two sites are so close, Coulson and Leonard (ibid.) suggest that Silvagou might have served as Kom Firin's cemetery in the New Kingdom.

Whilst Kitchen (1999:328) suggests that these Late Bronze Age remains might represent the only surviving fragments of a border fortress dating to this era, only further work may identify exactly what the nature of activity was here and whether or not any of the recorded fortifications date to the New Kingdom and not later periods of occupation.

Kom el-Hisn, 12km to the south-east of Kom Firin, once possessed significant New Kingdom remains, although today many of these have been lost through agricultural expansion and various other depredations (Wenke 1999:416).

In 1881, Petrie visited the site and located a statue dedicated by Ramesses II to Sekhet/Sekhmet-Hathor, "lady of Amu/Imau" (Coulson & Leonard 1982a:213; Kitchen 1996:291-292; Petrie 1886:95). Amu/Imau was the ancient capital of the Third Nome (or district) of Lower Egypt, the "District of the West", from the New Kingdom onwards and it is likely that it can be identified with Kom el-Hisn (Kirby, Orel & Smith 1998:25; Wenke 1999:416).

Griffith (1888:77-81) surveyed the site on occasions between 1885 and 1887. He was able to identify what he believed to be the remains of a mud-brick temple enclosure measuring 65m by 115m, defined by a wall almost 4m thick (Griffith 1888:77; Kirby, Orel & Smith 1998:23-25). From these remains it is likely the site acquired its name, which translates as "Mound of the Fort" (Wenke 1999:415-416). Within the enclosure, Griffith (1888:77-8) found four statues dating to the reign of Ramesses II, one certainly being that previously identified by Petrie. Three of these were relocated when the Naukratis Project surveyed the site (Coulson & Leonard 1979:163-167, 1982a:213; Brodie et al 1981:81-85). Much of what Griffith described has been eradicated over the years, but work at the site since 1996 by the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) has resulted in the relocation of the back wall of the temple (Kirby, Orel & Smith 1998:41).

It has long been suggested that a fort may have existed at Kom el-Hisn. Between 1943 and 1949, Hamada, el-Amir and Farid excavated many graves dating to the Middle and New Kingdoms (Hamada & el-Amir 1947; Hamada & Farid 1947, 1948, 1950; cf. Brunton 1947). One class of New Kingdom burial was rather interesting, this being the category said to represent "warrior" graves. These frequently contained multiple interments and incomplete bodies, accompanied by axes and daggers (Hamada & el-Amir 1947:103-105, 107, 110-111). This was enough to convince the excavators that this was the scene of a battle against invading Libyans and that there may have been a fortress here (Hamada & el-Amir ibid.).

The site sat near to the desert edge in antiquity, possibly on the route towards the western frontier (Wenke 1999:416), which may have resulted in it being plagued by Libyan incursions and, thus, needing defences. That this region may indeed have been troubled by Libyans is recorded on a statue dating to the reign of Amenhotep I which describes its owner as being involved in a military campaign against the Libyans "north of Amu" (Kirby, Orel & Smith 1998:42; Kitchen 1990:15; Muller 1888:287).

Therefore, in the New Kingdom, Kom el-Hisn may have had some strategic significance. It is possible that the site may once have been one of the ancient fortified settlements said to be "on the Western Waters", referred to above. Kom el-Hisn has been shown to have been associated with a now extinct Nile branch, perhaps the Canopic Nile, by work that followed the Naukratis Project's survey of the site (Moens & Wetterstrom 1988; Wenke 1986, 1990, 1999; Wenke & Brewer 1996; Wenke & Redding 1985, 1986; Wenke et al 1988).

One of the stated aims of the current EES work at the site is to search for evidence of a Ramesside fortress (Kirby, Orel & Smith 1998:42). However, it may be that this has already been located and not realised.

Perhaps the so-called temple is, in fact, the remains of a fortress. The enclosure has never been entirely defined. Much of it had been destroyed or was obscured even in Griffith's day and so the accuracy of his plan is perhaps debatable. It would also be very unusual for a significant temple in a nome capital to be made of mud-brick (Kirby, Orel & Smith 1998:37). When one considers this, along with the fact that the "temple's" mud-brick walls are comparable in size to those of Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham and Kom el-Abqa'in, is it conceivable that this structure represents the remains of a fort as the Arabic name suggests? And could perhaps here, at the capital of the "District of the West", be the location of the of the "the fortress of the west"??

Kom el-Hisn was undoubtedly an important settlement site with evidence of activity over a long period, including the New Kingdom, and also seems to have been the scene of some conflict. Whilst no conclusive evidence of a fortress has yet been located, hopefully further work at this promising site may change this.

The name Kom Abu-Billo refers to the north-western part of the modern village of Tarana, known to the ancient Egyptians as "House of Hathor, Lady of Turquoise" (Mefkat for short) and to the Greeks as Terenuthis (Hawass 1999:414; Kitchen 1999:327). The site is located 38km south-south-east of Kom el-Hisn and some 70 kilometres north-west of Cairo. It is particularly noted for its remains dating to the Graeco-Roman and Coptic period (c.300BC-500AD), which include thousands of tombs (Abdel Aal 1983; el-Nassery & Wagner 1978; el-Sawi 1977; Farid 1973; Hawwass 1979; Hooper 1961). At this time, the settlement was a major trading centre, particularly of wine and salt (Griffiths 1986:424; Hawass 1999:415).

More relevantly, the site was the location of activity in the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms judging by its cemeteries which span these periods (Farid 1973:22-23; Hawass 1999:414). But little evidence of the settlement with which these burials were associated has been found and precisely what was happening here in the New Kingdom is difficult to establish.

Beyond the cemeteries, the only evidence of activity at this time seems to be a limestone block described by Edgar (1914:281), which bears the names and titles of Ramesses II (Kitchen 1996:291). Also, 10km east of Kom Abu-Billo, in the vicinity of Minuf, certain reused blocks from the time of Ramesses II have been located (Daressy 1913:193; Leclant 1974:174); it is quite possible that these pieces originally came from Kom Abu-Billo.

The cemeteries indicate that a settlement did exist in the area from the Old Kingdom which might, by the reign of Ramesses II, have required fortification. Kitchen (1999:327) suggests that this site may have been the southernmost in the chain of fortified settlements. As Daressy (1913:200) points out, Kom Abu-Billo is at the head of the ancient route between the Delta and the Wadi Natrun (for location, see map above), a route along which hostile forces, e.g. Libyans, may have travelled. If correct, to fortify the settlement at Kom Abu-Billo would have made sense. However, there is no concrete evidence of what structures or fortifications existed at Kom Abu-Billo in the Late Bronze Age.