Maintenance

Carb Tuning and Adjustment

| Home | |

| Maintenance | |

| Riding Skills | |

Adjusting the Mixture

To the inexperienced, adjusting carburetting can be great fun. The novice whose bike has four carburetting can spend many happy hours tinkering with mixture screws, checking vacuum gauge readings and playing with the balance screws, all in a futile attempt to eliminate a rough idle which is being caused by a faulty spark plug ! Before even attempting to adjust the carbs on an engine it should be ensured that the rest of the unit is in otherwise perfect tune.

IF possible, a compression check should be made as the first step, to ensure that the valves and bores of the engine are all in good condition. A low reading on one cylinder will make all attempts at obtaining a smooth idle a waste of time. The spark plugs should be cleaned and gapped and, on a two stroke, the exhaust system should be checked to make sure that it is thoroughly devoid of carbon build up. It is also important to check that the air filter is clean. As the filter will be disconnected during the tuning operation it will not affect the running until it is reconnected and the bike is ridden away. A dirty filter will cancel out all the time and effort that has been put into setting up the carbs.

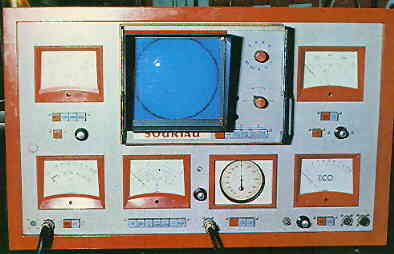

Electronic engine tuning apparatus incorporating exhaust gas analyser,

ignition oscilloscope, dwell meter, tachometer and vacuum gauge.

While you would not expect a TV repair man to attack the back of your set with an axe it is possible for an experienced man to set up a four carburettor engine with a screwdriver, four lollipop sticks and a lump of rubber hose, To be more realistic, at least one vacuum gauge will probably be needed alongside your lolly sticks and screwdriver. Before going into any details of how to set up a carburettor it is necessary to consider exactly what is the object of the adjustments and what settings have been predetermined by the makers of a particular machine. With a single carburettor engine, the only adjustments that can be made are to the idle system. There are two screws to set, one altering the actual mixture ratio of the petrol and air that the engine digests on idle and the other determining the speed at which the motor ticks over. The adjustment of a single carburettor is extremely simple. The mixture screw should be altered until the engine ticks over smoothly, consistent with a clean pick up as the throttle is opened. It may be found that after adjusting the mixture screw to its optimum position the idle speed will be too high. The throttle stop screw is therefore used to determine the speed of idle. The rest of the settings will have been pre determined by the manufacturer when the engine was developed. That, however, is not the end of the story because, like people, no two engine units can ever be exactly the same.

Due to production tolerances some engines come off the line much tighter than others, yet they are all fitted with the same carburettors, which in themselves can vary as to the mixture ratios that they will dispense, despite being fitted with the same jets and slides. It is partly for these reasons that two otherwise identical engines can give vastly different power outputs. It is possible therefore to tailor the carburation to suit the individual engine provided access to sophisticated equipment such as an engine brake is available.

Problems again arise because most carburettors are mass produced and consequently many of their characteristics are predetermined by the form of air corrector drillings; these cannot readily be altered. For this reason it is not usually feasible to transfer carbs from one machine to another, even though they may look alike and have the same choke size. Although it is possible to obtain a carburettor that can be adjusted by means of chokes and jets to suit any engine, the cost of such instruments prohibits their use on mass produced motor cycles.

.......

.......

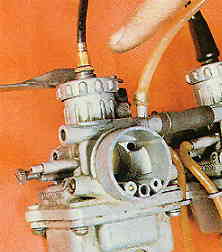

Above left : the finger points to the throttle cable adjuster.

Above right: adjusting the mixture screw with a screwdriver

Owners of large capacity, multi-carbed motor cycles can gain the impression that carburettor tuning will only affect the idle, and be reluctant to attempt any adjustment. In practice, a powerful bike will cruise on the open road with the throttle only open to about one eighth of its full travel and at this setting the idle mixture is still contributing significantly to the carburettor. For this very reason an engine with the idle mixtures poorly set will use more fuel when cruising than one properly set up. Well-balanced carburettors will also contribute to the physical long life of the engine as all the cylinders will be pulling together instead of working against each other. Having established that carburettor adjustment is worthwhile we can now take a look at the procedure. As has already been stated it should be ensured that the engine is worth tuning before work is started and also that it has reached its correct operating temperature. Nothing is more frustrating than setting up the cards only to find that your settings 'go out' after a short run because the engine was not really hot enough when the work was done.

Assuming the carburettors are badly out of tune, the first step is to loosen off the linkages or cables to check that they are not holding the throttles open.

The next step is to determine which screw does what. There is no point in adjusting the "mixture" screw only to find it draining the float bowl. A hand- book or manual will show which screw is which. The mixture screw should first be set to its standard position as given in the handbook. This will be around one to two turns out from fully home depending on the make of carb. It should be noted that fully home does not mean that the screw should be tightened with the biggest driver to be found. Excessive force on the mixture screw will certainly damage the taper and may even scrap the carb by breaking the body at the pilot drilling.

Having set the mixture screws, the next operation is to adjust the throttle stops, or idle screws as they are often referred to. For this operation one or more vacuum gauges will be needed, or a piece of rubber tube and one very experienced ear that can tell a carb intake hiss from a rear wheel puncture. As few people have the experience or confidence to work by ear, use of a vacuum gauge, or gauges becomes necessary and these will have to be damped out. Quite simply this means that the take off for the gauge needs a restriction, or small hole in it, to damp out the fluctuations in the vacuum which occur as the inlet valve opens and closes. A single gauge can be effectively damped out by clamping the take off rubber tube until the gauge needle is steady enough to read. It should be remembered that the steadier the needle is, the less sensitive it is to smaller variations in pressure and some compromise is necessary.

After starting the engine the gauge is connected to each intake in turn and the throttle stop adjusted until the same reading is obtained for each carb. Once the carburettors are thus balanced the idle speed is adjuster by altering each screw by the same amount and then the balance is rechecked.

The fine tuning of the mixture screws can, in theory be carried out by altering the mixture screw to give the highest reading on the vacuum gauge but in practice the needles are rarely steady enough. A more reliable method is to alter each of the screws by the same amount, within one half a turn of the standard setting, until the engine runs smoothly. A method that is often recommended for setting up the mixture of twin carbs is to stop the spark to one cylinder and tune the remaining one as for a single, then repeat for the other side. The problem with this method is that the carburettor being tuned is only being set to its optimum position when the second cylinder is acting as a passenger.

|

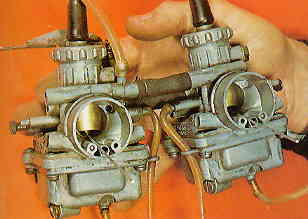

Left: balancing twin carburettors using two pieces of wire (lollypop sticks would do) . As the throttle is opened, so the sticks will move, indicating balanced or unbalanced carburettors. |

This means that with both cylinders firing, the idle mixture is no longer correct. On the subject of balancing, we have previously mentioned the use of a rubber tube and this, literally, coupled to an experienced ear, can be used to set up the balance but not the mixture. The idea is that one end of the tube is held to the ear and the other end is put up against the carburettor intake, with the air filters removed. The intake hiss can then be listened to. By adjusting the stops until all the carbs are 'hissing' with the same note the same result can be achieved as with the vacuum gauge system. Alternatively carb balancers are available which are held over the intake to measure the intake air speed. They tend not to be as accurate as the traditional vacuum gauge.

At this stage the engine should be ticking over quite nicely but will probably still not pick up cleanly. This problem will disappear once the throttle rods or cables have been balanced. The basic idea is to have some free play in the operating linkage so that the throttle slides are always free to rest on their respective stops but they must also all lift at the same time. If they do not all lift together then some of the cylinders will try to lead the others and in fact will always be trying to do more than their fair share of work, so the engine will run roughly as it is no longer in balance.

It is at this stage that we can introduce our lollipop sticks ! By tucking a short length of rod under each slide, so that it is just visible in the bellmouth, it should be possible to see the slides move as the throttle is operated.

The linkages can then be adjusted until the rods all begin to move at the same time. When fitting the rods it should be ensured that the slides are not being lifted off their stops, which would be defeating the object of the exercise. An alternative method, given sufficient access, is simply to look down the throats' of the carbs and note which slides are opening late.

The foregoing relates to fixed jet and Amal type carburettors but there are other types of carburettor which have no throttle stop screws. This is usually the case on fairly new bikes fitted with constant vacuum carbs, a type which BMW have used for some time.With this type of carburettor the air slide is replaced by a butterfly, as on most cars. Once these are balanced at tickover they remain correct, as the twistgrip is normally only connected to one carb and this operates the others. The BMW, of course, because of its engine layout still demands the use of separate cables. On most bikes the balance is determined by having the butteries linked via a spring loaded clamp which is adjustable via a small screw. Altering this screw changes the butterfly position in relation to it's neighbour. Once the carburettors are in balance the overall engine speed is set normally by a knurled screw arrangement. This is fine if the carburettors are mounted next to each other as on a straight four engine but the BMW has to have one carb on either side of the engine and linking them with a two foot rod is not practicable. BMW have stuck to cables for this reason.

Cable adjustment is one aspect of carburettor adjustment that is often overlooked. Apart from being regularly checked for signs of impending failure, the cable or cables should also be checked for adjustment after setting up the carbs. Some free play at the twistgrip should be allowed or the cable may be doing the job of the throttle stops and causing an uneven tickover. Many modern machines are now fitted with a closing cable which should also have its fair share of free play. lf the closing cable on some machines is over adjusted it can actually bend the linkages and then major problems will arise in getting the carburettors to balance.

www.vjmw.org

The Garage - Carburettor Tuning