PUPLIC

PARTICIPATION

Page 1

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND PARTICIPATORY PROCESSES

Page 2

WHAT

IS PUBLIC PARTICIPATION?

Page 6

DIFFERENT

WAYS

TO INVOLVE THE PUBLIC

Page 7

ROUND TABLES IN CANADA

Page 9

USING

ROUND TABLES IN THE TRANSPORTATION SECTOR IN POLAND

Page 10

URBAN

GREENING. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN

BANGKOK

Page 13

ENLISTING THE PUBLIC TO CLEAN UP CITIES

Page 15

EMPOWERMENT

AND PUPLIC PARTICIPATION

Page17

ICSC'S

ROLE AS A BROKER

Page 20

ICSC'S

CANADIAN TEAM-

PUPLIC PARTICIPATION AND MULTI-PARTY PROCESSES

Page 21

DOWNLOAD

TEXT ONLY

|

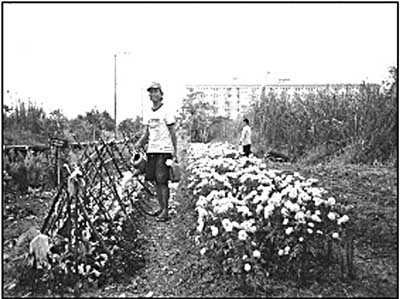

URBAN GREENING - PUBLIC

PARTICIPATION IN BANGKOK1

Evan D. G. Fraser

Since the spring of 2000 ICSC has been engaged on

a CIDA funded project with the Thailand Environment Institute

(TEI). While the goal is to increase green space in Bangkok, it

quickly became apparent that community participation was the heart

of the matter. It would have been possible to work with the Thai

government to gain access to abandoned land and hire people to

build parks or gardens. While this would have created green space,

it would not have had much to do with economic, social or environmental

sustainability.

TEI and ICSC put community participation at the

centre of every project. Two low-income communities, one in Bangkapi,

the other in Bangkok Noi, were chosen and the goal became to help

the communities plan and implement their own green plan. The key

has been to educate residents about the benefits of urban forestry

and agriculture and then to provide guidance in the design and

implementation of an urban green plan.

The first task was to conduct a workshop for community

members in order to teach about the benefits of urban greening.

This one-day workshop brought approximately 20 members of each

community together, along with speakers from the Bangkok Metropolitan

Administration and local universities. The speakers discussed

- environmental problems in the city

- how urban agriculture can help reduce poverty

- how urban forestry can reduce air pollution and make cities

cooler

- tree care and maintenance, and

- how to conduct an urban greening programme

By the end of the day, each community had drawn

a preliminary map of their community, established a working

group, and started working on a greening plan for their neighbourhood.

While the most obvious goal of the workshop was to educate,

it was also designed to empower the community members to become

stewards of their land.

After the preliminary workshop a planning day

was organized in each community. This planning day included

staff from TEI and ICSC, a landscape architect from the BMA,

and the community working groups. The first task was to create

a map of the new green space that also included existing trees,

buildings, utilities, and canals. This map served two functions.

First it became the basis of the urban green plan that the

community was about to develop. Second, and perhaps more importantly,

inventorying the community in this way made residents evaluate

their local surroundings as part of the greater environment.

The map became a tool that helped raise the level of awareness

among residents about their environment and how they could

address environmental problems. Using the map as a guide the

communities then drew up a list of goals that they hoped to

achieve with this project. These goals included increasing

the amount of shaded areas and planting community gardens

both for personal consumption and for sale. The map was then

used to plan out the specifics of the green plan. Finally

the community drew up a list of tasks and assigned responsibility

for those tasks. Throughout this process staff from TEI and

ICSC met with local government officials to ensure that municipal

and neighbourhood administrations would support this project.

Implementing their plans between July and October 2000, the

two communities organized their working groups and were supported

by local governments through the donation of labour, equipment

and planting materials (trees from municipal nurseries and

seed sources). In Bangkapi, residents selected two small areas

(20m2 each) within the community that were overgrown with

weeds and garbage. The community cleared these areas and planted

a diverse arrangement of local species to provide shade in

the future. Along one side of the community runs a canal,

the banks of which were filled with weeds and bushes. The

community then cleared a 5 m wide, 300 m path along one side

of the canal and planted fruit trees immediately adjacent

to the canal to stabilize the banks and prevent erosion. They

then turned the remaining space into very diverse intensive

garden plots. 10 families currently have plots, and that which

is produced but not consumed is sold at the road side. Residents

estimate that each plot could generate 2000 Baht/month (roughly

$55 US). As the average family income in this area is about

10,000 Baht, garden plots have the possibility of increasing

household income by 20%.

Bangkok Noi chose to develop a 55x55m field

that was in the centre of the community. Along one side of

this field is a band of trees and brush. Considerable amounts

of construction materials, old bits of concrete, and other

garbage had been dumped here. In this case the community chose

to prune existing trees, remove the brush and garbage, plant

new trees in the field and establish an interlocking brick

walking path through the area. There are plans for the local

school, which is next to the site, to plant a vegetable garden

but this has not happened yet.

1 For more details see the project

web site at: www.icsc.ca/urban/main.html

Page 12 Page 13 Page14

GO TO

PAGE1, 2,

3, 4,

5, 6,

7, 8,

9, 10,

11, 12,

13, 14,

15, 16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

Copyright ICSC 2000

|