In Meo Patacca, Rome's role goes well beyond that

of a simple background or a passive setting. The city interacts with the

plot, with the personages, as in the passage where Tolla gets lost in the

crowd caused by the castle's fireworks display, or in the passage

where the ghetto is placed under siege. Although the houses of Meo,

Nuccia, Calfurnia, Marco Pepe, etc. only existed in the author's

imagination, several sites where action takes place are specifically

involved; Berneri does not only mention them, he describes them, almost

as if they too were taking part to the story.

The aim of this page is to briefly review these sites, also to

compare their present look with the one they had in the 17th century,

which in some cases was quite different.

CAMPO VACCINO

Meo's speech to the braves (Canto I),

Meo's duel with Marco Pepe (Canto IV),

the public presentation of Meo's troops (Canto VI)

What Berneri describes as an uninhabited place,

off the beaten track, where the braves challenged themselves with terrible

stone-fights, was but the present archaeological site of the Roman Forum.

The ups and downs of this area, from pre-Roman times to nowadays,

give reason for its different looks in time.

the Roman Forum, as it appears today |

At first, a simple valley, where the

people who lived on the top of the nearby hills gathered

every eight days to sell and buy goods, away (foras in Latin) from the territories

of their respective tribes; then the elegant downtown of the republican and

imperial city, where the main temples stood; then an abandoned area,

and then, as of the 15th century, the site of the cattle-market (whence the

name Vaccino); finally, but only since the mid 1800s, the most renowned among

the archaeological sites of modern Rome, to which the old name "Forum" was

given back. |

Due to this spot's original importance, it could have not been located elsewhere

but in a crucial position, between the Capitolium hill and the Colosseum's

imposing mass, and between the Palatine Hill and the Esquiline Hill

(by whose base was the ill-famed Suburra district, ancient Rome's Bronx).

Since the beginning of the Middle Ages (5th-6th centuries) this area

appeared more and more neglected, with its several building more and more

damaged.

Having been Christianized, now Rome's main religion

no longer needed temples built in the old fashion, and there was no reason

for caring about the ancient pagan ones.

Actually, precious building materials were taken

from the Forum, for the making (elsewhere) of houses, churches,

and other public buildings. This was a die-hard attitude, as the

famous "big fountain" on the Janiculum Hill, at the beginning of

the 17th century was still built by using marble mainly taken from the Forum of Nerva.

Time, carelessness and the barbarians did the rest, and in a relatively short time

the only thing left of the Forum was its wide space, covered with

ruins that could not be reused.

As earth, rubble and trash kept piling up, in Meo Patacca's days,

i.e. one thousand years later, its look had turned into that of a field,

a large "hole" in the middle of a fully rebuilt and urbanized Rome,

where broken columns and other fragments belonging to temples

kept sticking out of the ground. The area had been adorned by a double row

of trees, as described by Berneri's verses; this matches perfectly what can be seen

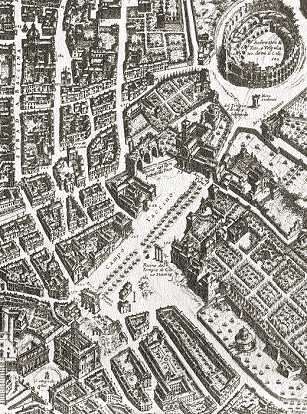

in the map of Rome by Antonio Tempesta (1676). |

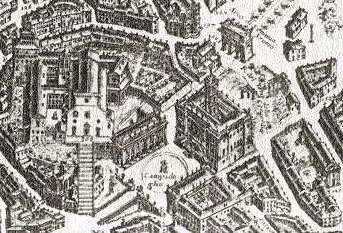

Campo Vaccino, in A.Tempesta's map;

note the double row of trees |

Campo Vaccino, in an engraving by G.B.Piranesi: by the end

of the 18th century, only a few scattered trees were left |

Despite the popes' interest for antiquity

had already been awakened since the Renaissance, and despite some

considerable finds had already been made in this area (such as the famous

reclining statue known as Marforio), a real excavation was not carried out

before the 19th century, very gradually at first, then systematically only

after 1870, i.e. after the city had passed from the hands of the pope to

those of the king of Italy.

Unfortunately, what archaeologists found,

and what we still see today, are mainly ruins.

|

|

|

IL CAMPIDOGLIO

the tournament organized and won by Meo (Canto XI)

The Capitolium Hill has already been dealt with by the page about

the

50 cent coins, that depict it, also

providing a better selection of images.

The top of the hill represented one of the first settlements of the future city,

and by its base, during the republican age, ran the Servian Wall, along which,

more or less where is now piazza Venezia, was the gate Porta Fontinalis,

now no longer standing, as well as most of this early set of walls.

In particular, the Capitolium was the site of the Temple of Capitoline Jupiter,

the wholiest place in imperial Rome. This height overlooked the Forum below, and

from the same Forum the priests reached the temple. In fact, unlike nowadays,

its northern side, which looked towards the Campus Martis, was a

steep slope, not easy to climb.

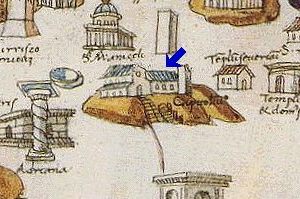

the Senators' Palace on the Capitolium (arrow),

detail from the map by P. del Massaio, 1472 |

As the adjacent Forum, or Campo Vaccino,

the Capitolium knew its darkest age during the second half of the first

millennium. After the destruction of the main temples, whose traces

have substantially disappeared, here the sheep grazed (monte

Caprino, "sheep hill") up to the 12th century.

Then, over the remains of the ancient Tabularium (archive),

the great Senators' Palace was built, and the site gained again its

social importance; here Rome's administrators, the Senators,

held their meetings. |

But besides the palace, the hill was still a simple slope, and after the

pedlars who sold food here during a sort of fair, periodically held, the hill

was nicknamed faba tosta (i.e. roasted broad bean).

Paul III (1534-49) had the idea of finally arranging

the top of the Capitolium, and charged with this duty Michelangelo, who

enlarged the preexisting building (further alterations were carried out by

G. Della Porta e G.Rainaldi) and added two buildings on the sides of the

square, Palazzo dei Conservatori and Palazzo Nuovo, the latter built over

half century later.

|

Capitolium Square, detail from A.Tempesta's map |

So, ever since, this has been the look of the famous square, that Berneri mentions,

as well: three large buildings, whose lightings shine from the sides of the square

up to its end (the Senators' Palace), and in the center the famous statue of

Marcus Aurelius, that Paul III had moved from the Lateran; Michelangelo,

yet opposing the idea of transferring the statue, drew its

high base, the one over which Nuccia climbs - taking the risk

of breaking her neck - to watch Meo's feats.

THE CORSO AND ROME'S CARNIVAL

the celebrations organized by Meo (Canto VII)

The Candle Race along the Corso (detail), I.Caffi, c.1850 |

What Berneri describes as an occasional

event, held for special reasons, is very similar to the standard celebrations

organized during Carnival, which took place in via del Corso and its

surroundings (see Curious and Unusual - 10),

whom the author was certainly inspired by in describing the joyful frolic

for Vienna.

The lightings were a constant element of this important roman 8-day festival,

which ended with a parade known as the candle race. The scarce visual

sources of this happening, such as the painting by Ippolito Caffi shown on the

left, give us a rather faithful impression of what Rome's streets may have looked

like during the celebrations organized by Meo. |

PIAZZA NAVONA

Meo's complaint against the slanderers (Canto III),

Meo's street performance of the siege of Buda (Canto XII)

This square, that many choose as the most beautiful in Rome,

has already been dealt with in the section about the

rioni, the old

districts (see

R.VI Parione), and also in

the page about the rivalry between Rome's two main Baroque architects

(see

Legendary Rome,

Bernini vs. Borromini);

further pictures of the square may be found in the aforesaid pages.

Born over the remains of the Circus of Domitian, whose shape it faithfully

reflects, the square was named after the games held in the ancient structure,

the Ludi Agonales.

The official names Platea Agonalis, or Campo in Agone, or

Foro Agonale, or the like, were still alive in the 17th century,

although in the common language the popular name Navona, sprung from the

corruption of "in Agone", was already used.

the Pamphilj crest

(move the cursor over the picture for the verses)

|

the lion coming out of the den

(move the cursor over the picture for the relevant verses)

When Berneri wrote Meo Patacca, the arrangement of piazza

Navona had been finished some forty years earlier, but its charm

undoubtly fascinated romans and foreigners alike, as if it had been

opened the day before. |

Therefore, we should not be surprised that Berneri dedicated

no less than twenty-one octaves of Canto III to the description

of the square and, among these, fourteen to the Fountain of the Rivers alone.

Instead, for the church of St.Agnes not a word was spent. This makes us

think that, while Bernini had a great success among the common people with

his work, Borromini, yet having built a very beautiful church, must have been

terribly envious!

Berneri gives a very brilliant description in verse

of the many details of the Fountain of the Rivers (a few examples are shown),

and this suggests how once the fountains, but also the statues and anything

that represented figurative art, was looked at by the common people in a very

actual way, a sort of virtual reality, almost as nowadays a videogame

or a computer simulation would be judged: this explains how the same people,

whose large majority was illiterate, played such an important role in

ordaining the success or the failure of an artist, according to whether

his new works (a statue, a building, etc.), were liked or disliked by the

commoners. |

the fish that swallows the water

(move the cursor over the picture for the verses) |

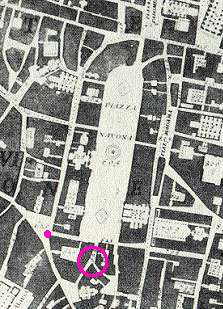

piazza Navona and its surroundings in

G.B. Nolli's map (1748); a circle marks

the site of the mock siege, while a dot

indicates Pasquino's corner |

|

Finally, in the last Canto, the mock siege of Buda

performed by Meo is set in a place just off piazza Navona.

The description provided by Berneri is once again so precise

(Slightly further, there is a space / Where vicolo

della Cuccagna ends), that it is possible to identify it with no doubt; the comparison

of old maps of Rome shows that the topography of this block alone has remained practically

the same as the one that inspired Berneri. |

|

present look of the place

at the end of vicolo della Cuccagna |

THE GIRANDOLA AT CASTEL SANT'ANGELO

the fireworks display from the Castle (Canto VIII)

|

Castel Sant'Angelo's girandola,

painting by Joseph Wright (1779) |

The Girandola was a very popular roman tradition, unfortunately

discontinued. It consisted of a display of several kinds of fireworks,

from the simple mortaletti, described in detail by Berneri,

to the more complicated ones, that burst into streams of coloured lights.

The celebration apparently dates back to the 16th century - it is said that Michelangelo

invented it! - lasting up to the second half of

the 1800s.

It was held on particular holidays, from the terraces of Castel Sant'Angelo,

so that as many spectators as possible could enjoy the show.

The coloured lights that rose from the Castle and reflected in the Tiber's water

must have really left the spectators in awe. |

|

|

Several authors left a description of the Girandola,

either in verses or as drawings, paintings and engravings by different artists

of different ages (H. van Cleef in the 1500s; F. Piranesi,

F. Panini and J. Wright in the 1700s; F.T. Aerni in the 1800s).

The most crucial moment of the display, as mentioned in Canto VIII,

at the end of the show, was the actual girandola, i.e. the simultaneous firing of a great number of

flares, a technique that apparently had been improved by Gian Lorenzo Bernini,

and whose glow ignited Rome's sky as during daylight, although it lasted

but a few seconds:

|

Son cose belle sì, ma a parlà schietto,

Il finir troppo presto è il lor difetto.

They are indeed nice things but, to be frank,

To last so little is their only weak point.

(Canto VIII, 73) |

|

Castel Sant'Angelo's girandola,

Francesco Piranesi (1783) |

|

THE GHETTO

the siege of the ghetto (Canto XII)

The ghetto, or "the Jews' enclosure", as it was called in the days

of Paul IV, who in 1555 decreed it, is fully dealt with in

Curious and Unusual - page 6,

where details and pictures may be found.

In Meo Patacca we read that the ghetto's gates, originally three,

had become four, plus a further small one: since the district had

become very overcrowded, with several thousands living there, the

pope had to order a slight enlargement of the enclosure's boundary.

|

the fish-market by the Porch of Ottavia, seen in the backround,

stood by one of the ghetto's gates (from an 18th century engraving by G.Vasi) |

More than the place itself, for which Berneri spends but a few words (It's

a rather miserable enclosure of streets, / As it is shady, and rather

saddening.), the author dwells upon the roman Jews' language.

piazza Giudia, outside the Ghetto

(engraving by G.Vasi): note one

of the gates, and the pole used for

punishing who broke the rules |

The Jewish-roman dialect, full of words and expressions derived from the Jewish language,

represented a somewhat parallel dialect to Rome's actual one,

certainly spoken by a minority, but with the same linguistic importance.

Unfortunately it has now become completely extinct, but this dialect too had

a good poet of its own, Crescenzo Del Monte (1868-1935).

Also Giggi Zanazzo, one of the first authors to show a deep interest in

Rome's dialect, did not overlook the Jewish-roman one, still spoken by the

turn of the 20th century; his work Popular Roman Traditions (1907)

contains a list of such words and expressions, a few of which are shown in

the following table.

|

JEWISH-ROMAN

| ENGLISH

|

|---|

| Alèffe; Bèdene; Ghìmene; Àrbano; Camìcia; ...-vaghézzi | One; Two; Three; Four; Five; ...and a half |

| Baruccabbà | Welcome |

| Bacurri; Iacodimmi; Sciabadai | Jews |

| Cacàmme | High Rabbi; Wise man |

| Cascèrro | Nice; Pure |

| Chénne | Yes |

| Chiùsi | Christians (= not circumcised) |

| Mònna | Madam |

| Picciurèllo | Penis |

| Scioscianìmme | Breasts |

|

Let us conclude with something curious.

At the beginning of the story, Berneri mentions some of the trendy

establishments of the late 17th century Rome, such as "The Three Kings".

via dell'Arco di S.Marco

(E. Roesler Franz) |

We cannot exclude that this may have been a fantasy name, as in those days many hotels and

inns were called "The Three Kings", also in other cities.

Among the famous water-paintings by Ettore Roesler Franz

(1852-1907), whose subjects are views of bygone Rome, there is one that features

via dell'Arco di San Marco, by piazza Venezia, a no longer existing street

after the district was heavily altered by the turn of the 20th century,

for the making of the bulky Vittoriano memorial monument. From one side of the view

peeps a small notice that says ALBERGO DEI TRE RE ("The Three

Kings hotel"); it is nice to think that this may have been the same one Berneri knew, while

Peaceful stood Rome

During year sixteen thousand eighty-three. |

|

|

|

The same place is also mentioned by Giuseppe Gioacchino Belli in a sonnet dated september 13, 1830, in which a commoner, chased at night-time by a Swiss papal guard, rushes along this street:

E con la patta in mano pijo l'Arco

De li tre Re, strillanno: « Vienghi puro ».

(La pisciata pericolosa, vv. 8-9)

|

And holding the flap of my trowsers

I flew past the Three Kings Arch, shouting: « Come and get me ».

(The Dangerous Pee, verses 8-9)

|